It is easy to understand why such a narrative took hold. The Confederacy did, after all, resort to far-reaching measures to address its population disadvantage. In April 1862 it adopted a policy of universal conscription, and in February 1864 it lowered the age of mandatory service from eighteen to seventeen. Additionally, some Confederate states enrolled boys as young as sixteen for service in state-controlled units. In contrast, the United States Congress passed a law in February 1862 barring the enlistment of youths below age eighteen, except as musicians, and the draft that it enacted in March 1863 applied only to men ages twenty to forty-five. The supposition that the Confederacy employed young soldiers more willingly and extensively than the United States has been reinforced by historical scholarship based on military records. For instance, in his classic studies of Civil War soldiers (The Life of Johnny Reb and The Life of Billy Yank), Bell Irvin Wiley used such sources to conclude that enlistees below age eighteen made up around 5 percent of the Confederate army, but just 1.6 percent of Union army.

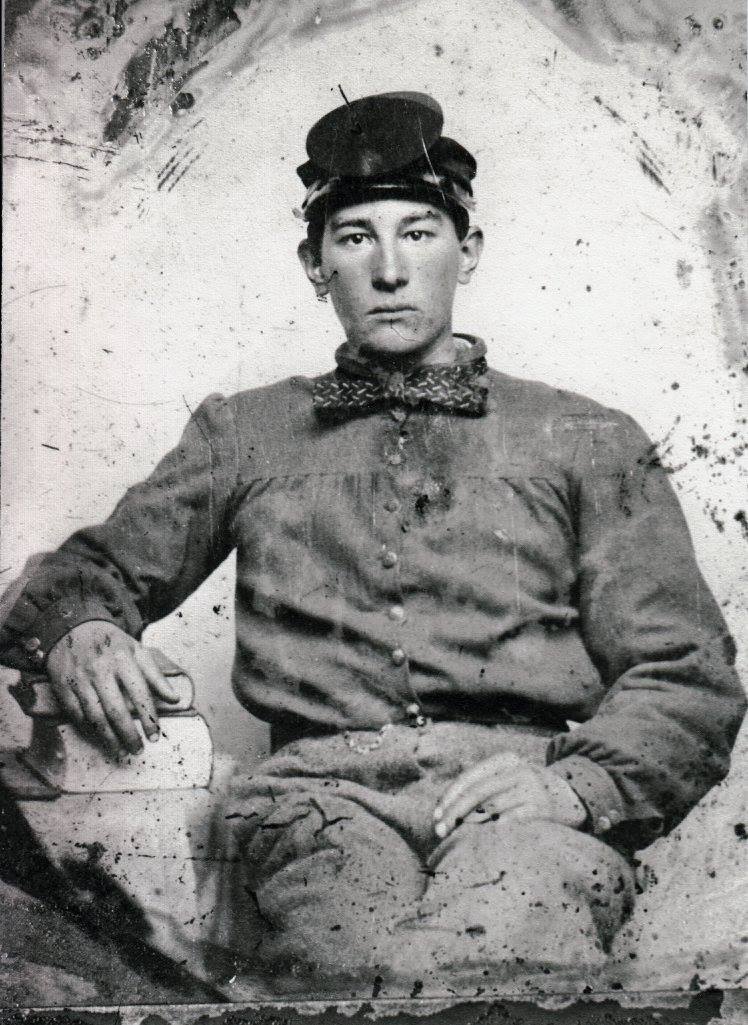

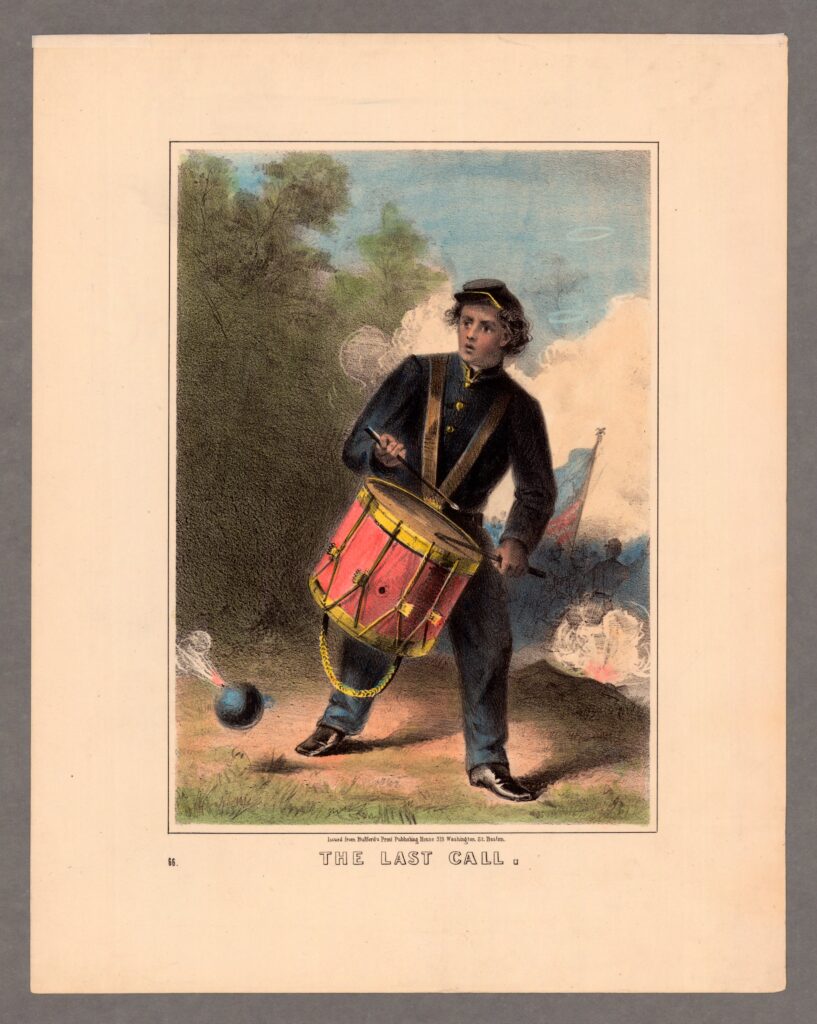

A more critical approach to military records, however, reveals a very different picture. While it remains difficult to calculate the percentage of underage Confederate soldiers, it is possible to arrive at a reasonably accurate estimate in the U.S. case, and the results are eye-opening. Our book, Of Age: Boy Soldiers and Military Power in the Civil War Era, shows that around ten percent of Union soldiers—some 200,000 enlistees—were below age eighteen when they joined the army. In other words, Union military records conceal an epidemic of lying. Although many Confederate boys also gave false ages, they were less likely to do so, because the Confederacy never legally banned underage youths from enlisting, provided they had parental consent, and because minimum age limits were less likely to be enforced.

Historians have not only underestimated the sheer number of underage soldiers who fought for the Union, they have also overlooked the significance of the legal, political, and administrative battles these youths provoked. U.S. officials fought tooth and nail to retain underage enlistees. By late 1861, the War Department was routinely blocking parents’ attempts to recover minor sons, informing them that their requests were at odds with “the interests of the service.” In February 1862, the same law that barred the military from accepting youths below age eighteen decreed that whatever age an enlistee swore to upon enlistment would be considered “conclusive.” Designed to stem the tide of parents petitioning for the release of underage sons, the practical implications of this stipulation were stunning: minors now had the ability to make themselves “of age” simply by swearing a false oath. Then, in September 1863, the Lincoln administration suspended habeas corpus across the nation, preventing state and local judges from hearing cases that alleged wrongful detention by the military. This meant that both paths for recovering underage enlistees—the administrative and the judicial—were now closed.

Convinced that the federal government surely did not intend to bar parents from promptly recovering underage sons, some political figures proposed alternative means for dealing with such cases, only to be stymied. For instance, the New Hampshire Governor Joseph A. Gilmore wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in November 1863, requesting that the military commander who oversaw his state’s volunteers be authorized to discharge underage youths, provided they repaid any bounty money they had received. But Stanton denied the request, insisting that such cases, “if there be any, should be reported, with evidence and facts,” to a federal office—that of the newly created Provost Marshal General. Even U.S. congressmen, who were answerable to local constituents and often heard directly from distraught parents, hesitated to take steps that might deprive the Union army of manpower. Although Congress enacted laws in 1864 and 1865 to stiffen penalties on lax and corrupt recruiters, such measures applied only to those who signed up boys below age sixteen, not the legal minimum of eighteen.

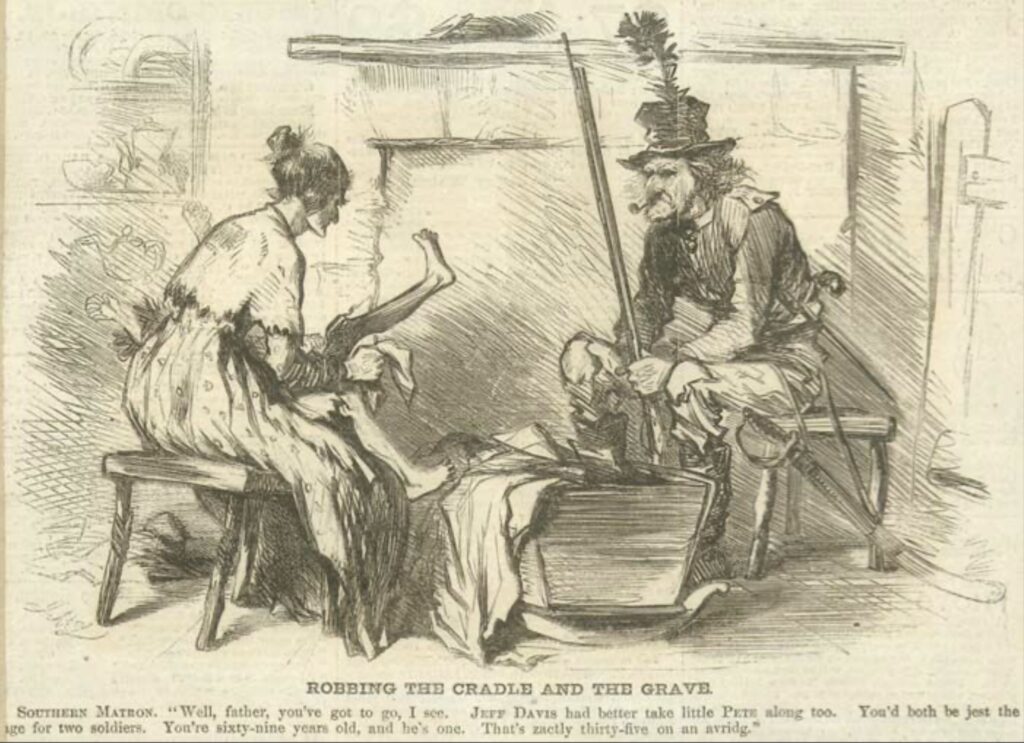

As the United States tightened its vise on underage enlistees, the Confederate response to youth enlistment remained inconsistent. Many thousands of boys and youths entered the ranks, but Confederate leaders at the highest levels repeatedly railed against underage enlistment, warning that it would be foolhardy to “grind the seed corn”—a line of argument rarely if ever advanced by Union politicians. On the whole, Confederate parents had more success than their Union counterparts in recovering underage sons. And while the Confederacy did ultimately lower its conscription age, the seventeen-year-olds were placed in junior reserve units in their home states, which typically entailed less onerous and dangerous duties than service in the Confederate army. Even near the war’s bitter end, when the government accepted the once-unthinkable notion of arming slaves, Confederate leaders declined to conscript boys below eighteen into the regular army.