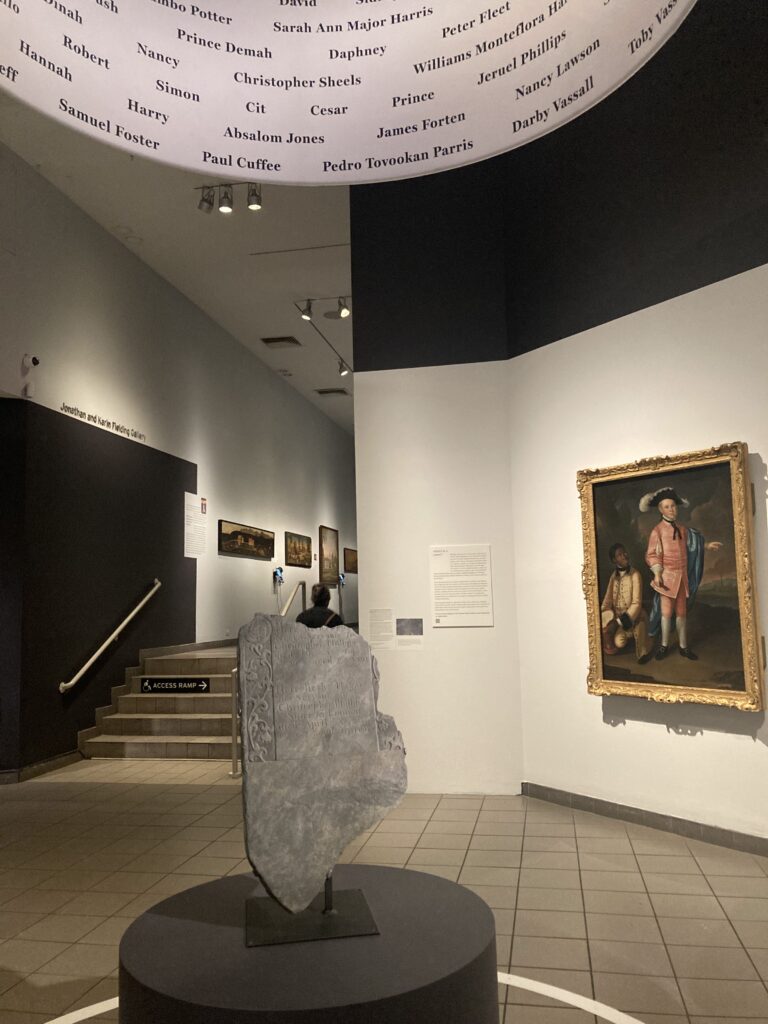

With this in mind, I would have placed the headstone with the names hovering above it in the nook that includes the exhibit about great Black craftspeople, creatives, scientists, and inventors like Phillis Wheatley and Benjamin Banneker. To maximize space, in the former site of the headstone, I would have removed some of the paintings on the wall. I say this because the greatest shift in the narrative about Black people that we need is about our intelligence—we need more attention placed on all of the inventions we developed in the early years of the United States and more emphasis on our creativity.

With “Unnamed Figures,” AFAM aligns with a burgeoning trend by other peer museums nationwide in their evolution of interpretations of legacy works. The exhibit, in its language guide about their reason for not capitalizing the “w” in White people, referenced the Baltimore Museum of Art’s language updates to their interpretation:

It can be appropriate and, indeed, restorative for curators to reconsider and update the title of an object—as in the case of the Baltimore Museum of Art’s recently retitled portrait “Charles Calvert and Once-Known Enslaved Attendant,” which has been known throughout its history by a variety of titles, including “Charles Calvert” and “Charles Calvert and His Slave.”

For “Unnamed Figure,” AFAM chose not to follow the route of BMA and instead kept the past title. They explained:

In the context of this loan-based project, we have chosen to provide past assigned titles as a reflection of the objects’ multilayered histories within multiple collections.

To educate the public even further about their language choices, AFAM complemented the exhibit with a language guide, accessible via a QR code on the “what’s in a name?” sign that takes viewers to the language guide in the Bloomberg Connects App. I commend them for this educational technology integration. While the exhibit is no longer at AFAM, if you are interested in viewing it, there is a virtual walkthrough of the exhibit on Vimeo.

A key component of the language guide explains the capitalization of the “B” in Black people and the choice to lowercase the “W” in White people. Understandably, AFAM’s reason for using White people with a lowercase “w” is to distance themselves from the practice of self-proclaimed white nationalists who capitalize the “W” in White people to assert the superiority of the White race. However, what we concede when lowercasing the “W” in White people are: (1) white supremacy is only something that white supremacists can do (it is not, white supremacy is a spectrum of human behavior that does more harm than good such as perfectionism), and (2) white nationalists have the power to control the narrative about race.

Capitalizing the “W” in White people does convey the power of whiteness, as it should, not from a white nationalist perspective, but because the power of whiteness is so subtle in our society, it is the air we breathe. There is behavioral science to support this claim. Yet we, especially White people, do not interrogate the power of their whiteness enough. And therefore, whiteness negatively affects the lives of people who are not White on a regular basis, for centuries, as evidenced in the interpretations in this exhibit. So, for us to see it as the powerful negative force that it is, this narrative that “White people and anyone who appears to be as White as possible are a standard for goodness, intelligence, and who is safe,” we must capitalize the “W” in White.

This practice of unredacting the facts of artwork and objects to tell a fuller story about them is prominent in AFAM’s peer museums in New York as well. As Karen Rosenberg shared in her review of the exhibit, “Now, Black Figures Have a Name, a Frame and a Show”:

Even as New York’s museums deliver a season of exhibitions in which the Black figure is emphatically, profoundly present, these institutions are reckoning with legacies of absence, invisibility and anonymity.

The article states that New York’s museums are, “reckoning with legacies of absence, invisibility, and anonymity.” But are the American Folk Art Museum with “Unnamed Figures,” and other museums really “reckoning with legacies of absence, invisibility, and anonymity,” if those who committed the erasure, White curators, collectors, and art historians, remain unnamed figures in the exhibits, redacted?

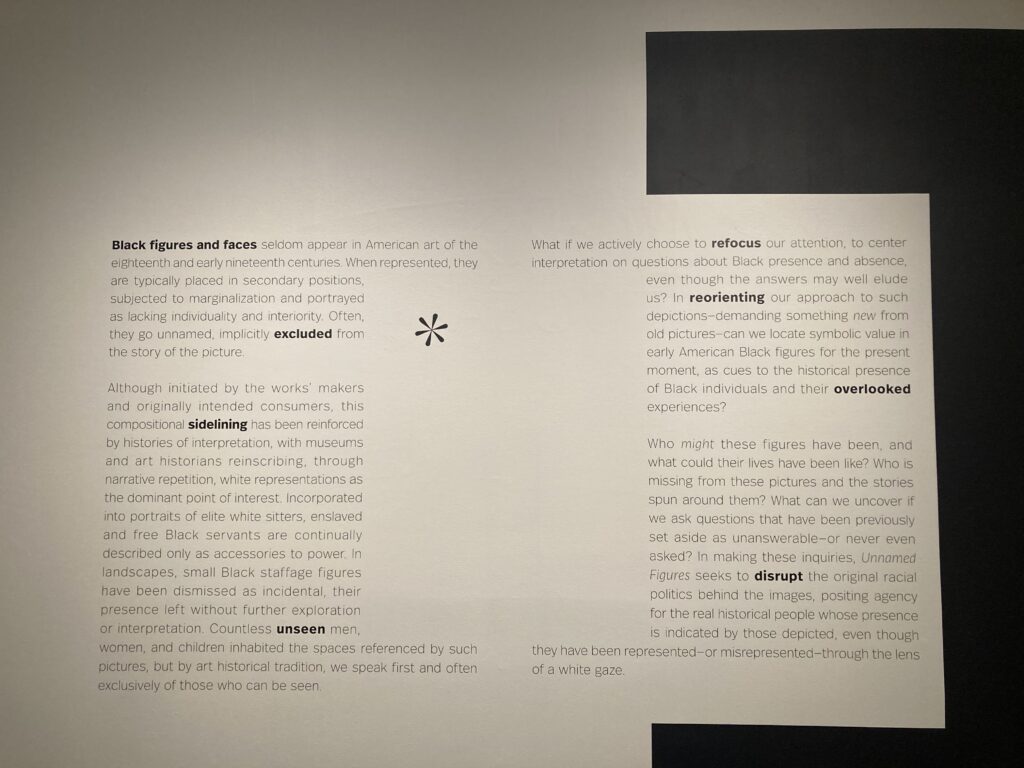

AFAM opens the exhibit with the following paragraph that makes no mention of who unnamed the figures:

Black figures and faces seldom appear in American art of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. When represented, they are typically placed in secondary positions, subjected to marginalization and portrayed as lacking individuality and interiority. Often, they go unnamed, implicitly excluded from the story of the picture.

AFAM filled the exhibit’s interpretive signs with one of the most prolific forms of redacted grammar and language, the passive voice, written from the perspective of a third-person narrator who omits themself from what they are witnessing. In this, the narrator, a White curator or someone adhering to white supremacist ideology has removed the White museum professionals from the erasure of Black figures and faces.