Unveiling the American Actor: The Evolution of Celebrity in the Early American Theater

Picture the following scene from a theater fan’s notes: it is 2005 and I am standing outside a theater in New York City with a poster and a marker after seeing David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross, a personal favorite. I have read this play at least a dozen times and seen the movie version with Jack Lemmon and Al Pacino perhaps as often, even though I find it inferior to the play. I am not ordinarily a person who stands outside theaters with a poster and a marker. I am, in my own mind, a connoisseur of the theater who takes great performances in stride. All this changes, of course, when Liev Schreiber, to my mind the finest actor of his (which is to say my) generation walks out the door and into a small knot of fans. Schreiber has been playing the part Al Pacino plays in the film, Richard Roma. He walks through the crowd and signs my poster. In my mind I have practiced calmly shaking his hand and saying, “Excellent work, sir. You are the best actor of our generation.” Instead, I eagerly (and rather loudly) blurt out, “Thank you so much! I will never hear Al Pacino in my head again when I’m teaching this play!” The Actor looks at the Fan, slightly astonished; then the Actor smiles, says “Thank you,” and quickly gets as far away from the obviously crazed Fan as possible.

Afterwards, pondering my total loss of cool as I rode the subway, I tried to get some distance from my gaffe by thinking about this episode in light of the early American theater, my main line of inquiry as a scholar. I found myself wondering what a similar experience would have been like in eighteenth-century New York for an actor or for a youngish man with intellectual and literary pretensions—the sort of theater fan I had (somewhat self-referentially) envisioned occupying the theaters of early America. Colonial New York may not seem like a must-see stop for arts tourism, but visitors to Manhattan have been going to the city’s theaters for well over two centuries. Royall Tyler, the young Boston attorney who wrote The Contrast, the first play by an American author successfully produced in the independent United States, was once such a visitor. Eighteenth-century actors and fans, however, related quite differently to one another than they do today. Liev Schreiber is a classically trained stage actor, but I first became familiar with him through the globally dominant American film industry. I had seen his widely circulated image many times before I saw him in the flesh; I could have recognized him on the street before the show. Before buying tickets to the show I read reviews of his performance in all the “right” sources (The New York Times, The New Yorker, and even Variety) sold to discerning theater fans by the publishing industry. The details of my trip to the theater to see him perform conformed to a twenty-first century tourist experience of Broadway: online advance purchase tickets, an Amtrak trip from Baltimore for a New York vacation, ads for Times Square restaurants in the free copy of Playbill magazine left at my seat. In other words, I encountered Schreiber through a culture industry looking to sell me tickets, whether for ten dollars in a multiplex cinema or a great deal more on Broadway. Nothing like our little interlude would have happened in the eighteenth century. Or would it?

Some of the elements of modern celebrity and fandom were already visible in the early American theater. Certainly the intensity of the fans was there, despite the fact that acting was hardly a profession toward which most Americans aspired in the eighteenth century. Admirers of up-and-coming actresses wrote poems praising their performances. Critics promoting rival actresses sniped back and forth in newspaper columns. Aspiring young men like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson attended performances whenever they could. Even young John Adams, locked away in Massachusetts, where there were no licensed theaters until after the Revolution, was a fan: he participated in amateur readings at Harvard before picking up the theater-going habit during his diplomatic and political career. Reading and attending plays, as well as performing amateur theatricals, were engrained in the culture of a certain segment of early American society.

The world of early American actors looks, if anything, even more familiar to us. A celebrity culture began to take shape over the course of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and there were a variety of theatrical paths to fame. Playwrights sometimes wrote plays with particular actors in mind. Sometimes performers wrote or commissioned starring vehicles for their own advancement. Many other strategies were open to ambitious actors, who could pursue fame by specializing in certain popular “lines” of performance, by associating themselves with dominant forms of gender behavior, or by stressing their national identity, whether European or American. Moreover, as the eighteenth century progressed into the nineteenth, media technologies advanced, decreasing the perceived distance between actor and fan. As a result actors, not plays, came to dominate the American theater. The actress Olive Logan recalled in the late nineteenth century that “With all their love for theatrical amusements, I have no hesitation in saying that the Americans care much more for actors than for the merits of the play itself.”

Logan’s comment sums up an attitude in the nineteenth-century American theater that sounds much like our own culture of celebrity. Both Logan’s world and our own differ from the world of early American theater-goers and performers, however, when it comes to the ubiquity of the celebrity’s image that we associate with contemporary fame. Fame in the late-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, at least in Britain, was intensely visual. Indeed, it changed qualitatively during this period due to technological innovations like mezzotint that rendered images much less expensive to produce and market. In the late eighteenth century, however, the circulation of performers’ images was far more difficult in North America than it was in Great Britain. Critic Trish Loughran observes that even during the end of the colonial era in North America, the only person famous enough to have instantly recognizable features was King George III until George Washington and Benjamin Franklin joined him in that category. As Wendy Wick Reaves of the National Portrait Gallery has pointed out, even Washington’s image took time to gain common currency: she documents an engraving of the British poet John Dryden from a 1773 New England almanac that is recycled as an image of Sam Adams in a children’s primer in 1777, then again as an image of Washington in another primer in 1799. Instant and universal visual recognition, it seems, was not an absolute condition of celebrity in the early republican era, even for those whose images circulated most widely.

This absence of instant visual recognition for even the most famous Americans in the late eighteenth century necessarily created conditions in the theater trade far different from what today’s star performers know. Given the relatively poor circulation of images, celebrity actors were far less common in the colonial and early republican periods than they were in Olive Logan’s day, to say nothing of our own. Moreover, as we shall see, these earlier theaters tended to work under ensemble conditions where the marketing of individual star actors was much less common than it would become in the nineteenth century. As the theater industry began to consolidate in the nineteenth century and the technology for reproducing images became ever more widely available, an apparatus for developing and marketing celebrity performers akin to the Hollywood star factory began to emerge, but in the pioneer phase of the American theater, celebrity was a far rarer and more speculative commodity. The actors who clawed their way to fame in the early decades of the American theater labored in an entrepreneurial industry that was far more reminiscent of prospecting for gold or financing merchant ships than it was of modern industrial production.

The beginnings of professional theater in the British North American colonies are somewhat obscure. The most likely first commercial performances occurred in 1749 and 1750 by a group led by two men named Murray and Kean, and scattered records exist of other performances around this time. In 1752, the London Company of Comedians, led by Lewis Hallam Sr., landed in Williamsburg and gave the inaugural performance of what proved to be the most successful pre-revolutionary theater company in British North America. The actors, all fresh from Great Britain, were entering largely uncharted territory. The market for theatrical entertainments in the colonies was untested and no metropolitan area could sustain a permanent theater company, which meant that the actors had to travel. Unlike other “British” goods—tea or textiles—consumed by North American provincials, theatrical performances faced religious opposition. New York’s Presbyterian community and Philadelphia’s Presbyterian and Quaker communities had deep reservations about the theater; in puritan New England, professional theater would not establish firm roots until after the Revolution. Moreover, since the actors typically charged specie (hard currency) for admission but operated as traveling companies who played for a period of weeks or months at a given location before moving on, local merchants periodically opposed the licensing of theatrical seasons. They feared the actors would drain a large share of the local money supply and then skip town—not to mention exerting a bad influence on young apprentices who would be drawn to spend all their free time and money at the theater.

The life of an actor in the London Company—which was later taken over by David Douglass when Hallam died and renamed “The American Company”—or one of its colonial competitors was, then, often quite difficult. Actors were nomads working their way from town to town by cart or on foot, and occasionally by ship, along the Atlantic Coast, with occasional forays to the West Indies in times of war. (Eventually, however, these troupes established a strong chain of theatrical venues that ran roughly from New York in the north to Charleston in the south.) An eighteenth-century theater company typically worked, moreover, according to a “share” system where performers received not wages but a certain portion of the profits, assuming there were any. Established members also got a “benefit night” where they took the house’s net profits, but this income was likewise undependable. Parts were assigned according to a system of “lines of business” (such as tragic leading man or “low” comedian) that tended to be rigidly hierarchical. Actors jealously guarded their parts in popular plays, which were generally treated as a form of property within the company. Complicating matters further, the repertory system meant that a traveling troupe like the American Company performed a different play almost every night.

Given the difficulties of establishing a theater industry in British North America, it is no surprise that individual actors did not achieve much fame. David Douglass, a master of marketing, concentrated his energies on “selling” his company to the most respectable men in any new city, often using his connections as a Freemason. Prosperous men eager to be able to see themselves as on par with metropolitan Britons—and colonial audiences were almost entirely male, respectable women needing an escort to attend—were a key constituency both for gaining legal approval to act and for selling profitable box seats during theatrical seasons. (Plenty of working-class men, as well as prostitutes, also attended the theater, although they were generally relegated to the upper “gallery” seats, which were sometimes separated from the lower seating levels by a spiked fence.) The very same class of prosperous men upon whom Douglass depended for patronage, unfortunately, banished his players in 1775 when the Continental Congress banned theatrical performances. The actors were forced to decamp once again for the Caribbean.

The professional theater’s exile lasted nearly a decade. In 1783, a troupe led by Thomas Wall in Baltimore acted a few plays. In 1784, Lewis Hallam Jr. brought some of the American Company back north. They eventually joined forces with a group led by another American Company veteran, John Henry. Harkening back to their own pioneering days before the war, this group labeled themselves as the Old American Company although, once again, the actors were almost entirely British by birth. The individual egos of the performers and the growing market for theatrical performances (which also led to actors being paid on salary), however, soon led to schisms. In turn, the rapid fragmentation of theater companies in the early republic helped to initiate an arrangement known as “the star system” and contributed to a much more recognizable form of celebrity culture. In 1792, Hallam and Henry recruited John Hodgkinson, who had played opposite Sarah Siddons in Britain; Hodgkinson quickly began lobbying for more parts, and by 1794 had become a joint manager and continued to collect more plum roles. In 1794 the popular low comedian Thomas Wignell, who had been recruited from Britain just before the congressional ban on the theater, left the Old American Company with several other veteran performers to create a company in Philadelphia, while other rival theaters soon emerged in New England and the South.

Wignell’s subsequent recruiting missions to Britain brought in performers such as the former adolescent prodigy Anne Brunton Merry; the rusticated university man James Fennell, who had been disowned by his family when he went on the stage; and Thomas Abthorpe Cooper, who had been raised as a foster son by the radical philosopher and novelist William Godwin. (A touch of romance in one’s biography didn’t hurt in the early American theater.) Cooper, recruited by Wignell in 1796, had by 1798 (with considerable legal difficulty) contracted with Hodgkinson and his new partner, William Dunlap, to play in New York. Under this “star” contract Cooper worked at a higher rate of salary than the typical member of a “stock” company would receive, and he was bound not to the company but directly to the managers, leaving him free to negotiate to play elsewhere. For the rest of his career, Cooper would be an itinerant star, moving between different theaters and playing set leading roles alongside local stock companies before moving on to his next engagement. The American evolution toward the modern celebrity system had truly begun.

Meanwhile, professional theater began to spread, both geographically and socioeconomically. Theaters opened in Boston and Providence, and as the country spread westward, new theaters could be found in such places as Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and New Orleans. Women, including working class women, appeared at the theater in greater numbers. New characters, such as the stage Yankee, the stage Irishman, and the stage Indian, emerged in response to shifts in the demands of the public for “American” shows, and a number of actors specializing in those roles emerged as stars. The working class audience of laborers, apprentices, sailors, and others (still including prostitutes) that filled the galleries, moreover, became increasingly boisterous during the post-revolutionary decades. Higher up the social ladder, some of the fashionable young gentlemen who began to attend the theater, such as Washington Irving, became increasingly discerning in their evaluation of the spectacles before them and began to evolve into drama critics. As a young man, Irving penned a number of essays on the theater under the nom de plume Jonathan Oldstyle for Salamagundi, the literary journal he co-founded with his brother William and their friend James Kirk Paulding.

As the theater matured and spread further across the continent and the social divides of the early republic, more and more talented performers left their stock companies and took to the road as traveling stars in search of fame and fortune. This trend culminated in the career of Edwin Forrest, the first American theatrical celebrity in the contemporary sense of the word, the first great native-born star of the American theater, and the first star to commission plays for his own repertoire. Forrest, who made his debut in 1820 and continued performing until his death in 1872, became an idol to working-class male audiences especially, a sort of surrogate Andrew Jackson. Forrest worked his way up from relative obscurity and poverty in Philadelphia by playing both Shakespearean leads and new, democratic heroes such as the medieval peasant Jack Cade and Spartacus, leader of a Roman slave revolt. Forrest, especially in his prime, was everywhere. Drawings, prints, and photographs of him, including caricatures of his rather prodigious head, circulated widely. Theater managers were forced to bargain with him and take his terms for salary and casting. Possessed of a collection of proprietary star roles and a fan base that saw in him the embodiment of what they believed it meant to be a patriotic American and a man, Forrest achieved an unprecedented degree of independence for a performer. His power to dictate his own terms in the theatrical labor market far exceeded what his predecessor Cooper or any other earlier star had achieved.

Forrest cuts a romantic figure of the star performer as a being liberated from the quotidian cares of employment in the theater industry. For other performers, the theater was not so liberating. Olive Logan was raised in Cincinnati, the daughter of an actor-manager who specialized in “Yankee” roles. As a young girl she debuted in children’s roles alongside touring stars like Forrest and Junius Brutus Booth. After retiring from the stage at sixteen to study in England and travel on the continent, she returned to the stage at the age of twenty-three in 1864 in a melodrama, Eveleen, which she had written as a star vehicle for herself. Never fond of a profession that she freely admitted she pursued solely as one of the few professions open to women in need of income, she retired in 1868 after a brief tenure as a star to pursue other interests as a journalist, lecturer, and advocate for women’s rights. In retrospect, her commentary on American audiences’ preference for players over plays suggests both the appreciative memories of a popular actress and the aesthetic displeasure of an incisive theater critic.

American audiences, however, did not always privilege players over the content of plays, especially in the early republican period, as illustrated by the theatrical career of Susanna Rowson. Better known as the author of popular sentimental novels such as Charlotte Temple, Rowson was raised partly in Massachusetts by her father, a British naval officer who was eventually seized by the Continentals, deported, and repatriated in a prisoner exchange. She returned to the United States along with her husband, moved more by economic need than artistic ambition. While performing with Wignell’s company in Philadelphia in 1794, at which point Charlotte was already available from Philadelphia booksellers, Rowson wrote Slaves in Algiers, a heroic play about Americans held captive by Barbary pirates. The controversy that attended this production illustrates the inherent difficulty of reintroducing British actors to the American stage and the specific difficulties that faced women onstage in the early republic. While Rowson’s overwhelming emphasis in the play is on the generically American ideal of “liberty,” one of her characters, an Algerian girl named Fetnah who has been sold by her father into the Dey of Algiers’s harem, expresses the desire that women should be as free as men. Meanwhile, Rowson delivered the play’s epilogue not in her starring role of Olivia, a captive of mixed English and American parentage, but as the author of the play. “Disguised” as herself, she comically turned the tables on eighteenth-century gender relations by informing the audience that “Women were born for universal sway, / Men to adore, be silent, and obey.” Rowson awakened the wrath of the arch-conservative (and fellow immigrant) newspaper editor William Cobbett, who in a pamphlet painted her as an aspiring petticoat tyrant and ally of French radicals while also questioning the sincerity of her conversion to the cause of American patriotism since her emigration from Britain. The controversy was brief, and Rowson went on to enjoy a successful, if short, theatrical career before retiring in 1797 to focus on writing books and opening a school for young women in Boston. Cobbett’s intemperate critique of her play, however, illustrates the difficulties in the life of a performer, especially an actress, in the tempestuous cultural climate of the early republic.

Logan, Forrest, and Rowson seem to have had very different experiences of fame. All of their careers, however, were wrapped up in contemporary discussions of national identity and gender that influenced the public perceptions of actors and their audience’s ability to relate to them. Their careers also coincided with a long period of expansion in American print culture, particularly the growth in the market for theatrical material in American newspapers and magazines, as well as the growth in the demand for printed plays. This profusion of print fueled the development of celebrity in the American theater by facilitating the development of professional and amateur theater critics, opinionated readers and viewers who found their own “voices” in print by championing actors and plays that met with their approval and pummeling those that did not measure up. Beginning in the 1780’s, enthusiastic fans of the theater found new outlets in print, whether in reviews and letters to the editor in papers such as The New York Daily Advertiser or, eventually, in magazines devoted to the theater. Such journals were, sadly, usually short-lived. The Dramatic Censor, a magazine that critiqued the dramatic offerings of the various theaters in Philadelphia, lasted just four issues between December 1805 and March 1806. The Polyanthos, a journal in Boston that published on a broader selection of artistic and intellectual topics and also sometimes printed engraved portraits of famous actors, fared somewhat better: it ran from December 1805 to September 1807, and was then resurrected from February 1812 to April 1814. Meanwhile, as Julie Stone Peters observes in her excellent history of play publishing, Theatre of the Book, printed plays of the eighteenth century increasingly featured prints of stage scenes or of leading actors. American printers and booksellers apparently took notice of these new features in plays imported from London and began to follow suit in their own editions.

Celebrity prior to the nineteenth-century triumph of the star system was, however, a far more localized phenomenon than our own version, and one much less dependent on visual images. Images of performers rarely circulated as separate prints, rather than as portraits in a journal or an edition of a play. The American Antiquarian Society’s Catalogue of American Engravings lists only six prints of performers prior to 1820, for instance, and almost no graphic representations exist of the colonial stage or its performers. The most famous image of the colonial theater, however, illustrates how perceptions of both gender and nationality influenced early American theater.

In August and September of 1770, the American Company was playing at Annapolis. The noted painter Charles Willson Peale painted a portrait in oil of Miss Nancy Hallam, the niece of the original leading lady of the company, Mrs. Douglass. Peale painted Miss Hallam as Fidele in Shakespeare’s Cymbeline. Fidele is actually the disguised Imogen, one of Shakespeare’s cross-dressed heroines. This role evolved into a classic eighteenth-century breeches role that emphasizes the charismatic force of performers who borrow traits from the opposite gender, as well as offering the chance to show off the legs of eighteenth-century actresses. The orientalist fantasia of Hallam’s costume shows off precious little of her legs and the figure’s posture is a bit awkward, but the performance, as captured in Peale’s afterimage, caught the attention of the local theater critics of Annapolis. Specifically, Nancy Hallam charmed two important young metropolitan émigrés: a colonial official named William Eddis and the Reverend Jonathan Boucher, Rector of St. Anne’s Episcopal Church, which was located very near the American Company’s theater on West Street. Eddis wrote an adulatory review of the show, singling out Miss Hallam, and Boucher composed verses praising both the actress and her portrait; these appraisals were printed in the local weekly paper, The Maryland Gazette.

Perhaps nowhere in the records of colonial theater is the importance of this medium to the establishment and preservation of a “British” cultural identity in North America clearer than in Eddis’s heady review or Boucher’s rhymes. Eddis hears in the metropolitan-born Miss Hallam an echo of Mrs. Cibber, for twenty years David Garrick’s leading lady at Drury Lane. He praises the American Company as equal to any of the provincial troupes in Great Britain. Yet his praise of Miss Hallam is vague, suggesting that she has achieved only a very limited sort of celebrity: “Such delicacy of manner! Such classical strictness of expression!” Miss Hallam is being appraised as if Eddis were tasting a cup of tea. Likewise, Boucher’s poem in praise of her has little to offer about the actress herself, aside from noting her ability to catch Shakespeare’s “glowing ray” and making neoclassical comparisons to Cytherea and Diana. (Indeed, the poem, while ostensibly dedicated to her portrait, praises Peale for capturing her likeness, but says precious little about the actress’s appearance.) Though these praises lack in the sort of specificity about performance or appearance that we might hope to get from starstruck young men of good erudition, Eddis and Boucher are part of a smart set of young gentlemen in Annapolis, and they are fashioning, albeit in the chastest manner possible, their own celebrity fetish. Eddis and Boucher find their Britishness and their connoisseurship reflected back to them in a well-trained performing body, not to mention the transgressive thrill of seeing that nubile body cross-dressed as a man’s. Their printed reflections on this spectacle do little to capture the performance for their readers, however. Peale, for his part, captured Miss Hallam’s graces in a more detailed but less reproducible medium than print: a canvas that provided a graphic representation of her performance and imputed to her a much greater degree of social standing than a colonial actor had any reason to expect. The oil portrait was, after all, the same medium for self-representation that the merchants and landowners of Annapolis chose to establish their own bona fides as prosperous Britons.

Ironically, Peale took this painting with him when he moved to Philadelphia in 1775, the year the revolution broke out and the year after Congress closed all theaters in the thirteen colonies. By the end of the revolution, Miss Hallam’s fame and that of the American Company as a whole must have faded markedly. The returning actors in Hallam and Henry’s troupes depended on rekindling the public’s pre-war memories in order to justify their suddenly alien presence. Whereas the first touring actors in the colonies had stressed the novelty of the pleasures of metropolitan culture for colonial audiences, Hallam and Henry stressed their familiarity with their audiences and a vague association with the Revolution in marketing the remnants of the American Company against the rival troupes that began springing up in the early 1780s. An essay in The New-York Packeton September 15, 1785, probably a plant by Henry, argues in favor of giving permission to play in the city to “an old company of players … who have a claim to remembrance for having lived amongst us,” rather than another group “who all but one or two excepted are British strangers.” (Virtually all of the American Company’s colonial and post-revolutionary performers were, of course, metropolitan Britons by birth.) Henry also stressed in a 1786 public address to a New York audience that the American Company had left North America for Jamaica only at the behest of Congress. “Ten years we languished in absence from this our wished for, our desirable home,” he explains, and though often solicited to return “we … refused, supposing it incompatible with our duty to the United States.” Pre-revolutionary fame and a sort of theatrical patriotism, then, become Henry’s arguments for readmission; Henry effectively “naturalizes” his company as good patriotic Americans. This sort of memorial association with major political events becomes contagious in the public memory of well-known performers of the period. As theater historian Odai Johnson has observed, one nineteenth-century theater manager, recalling an inaccurate anecdote about the death of Mrs. Douglass, the American Company’s first leading lady, places her 1773 death in a Philadelphia house near the theater. The house later became a tavern known as “The Convention of 1787,” featuring an image of Franklin and a couplet dedicated to the Founders on its sign. The manager’s faulty memory is not quite an act of historical revision on the scale of the villagers in Washington Irving’s “Rip Van Winkle” painting over their tavern’s sign of King George with the image of General Washington, but it’s not bad.

Mrs. Douglass, who was widowed and remarried in Jamaica in the 1750s while the London Company waited out the French and Indian War, probably would have approved of this revision of her obituary. She too was adept at image manipulation: shortly after her remarried return to North America, she played the tragic mother Lady Randolph in the Reverend John Home’s medieval Scottish tragedy of Douglas, presumably working the audience extra hard during the doomed lady’s epilogue: “This night a Douglas your protection claims, / a Wife, a Mother, Pity’s softest names!” This sort of appeal to a purported feminine need for protection by an actress, particularly if said actress was an import, was often used in promoting their rise to stardom. Consider the case of Mrs. Kenna, brought over by Hallam and Henry’s American Company from the Smock Alley Theatre in Dublin, along with her less-talented family, in 1786. By 1787 not only the company but also New York’s self-appointed theater critics had divided over the relative merits of Mrs. Kenna and the company’s other leading actresses, Mrs. Morris and Mrs. Harper. While Mrs. Kenna’s fans praised her power to excite the passions of spectators in great detail, her detractors pointed to a haughty streak that led to her being hissed after taking a comic part from the more senior and comically gifted Mrs. Morris. Mrs. Kenna’s champions, rallying to their tragic heroine, ran a printed appeal on her behalf that effectively repositions her in a melodrama of the audience’s making: “As a number of Gentlemen, and some ladies, cruelly combined to ruin Mrs. Kenna’s theatrical fame, and deprive her of bread in a strange country where she has not a friend or relation, and was totally unacquainted with the genius, customs, and manners of the country … we expect [they] will expiate their offence and mitigate the wounded spirit of a blameless woman by their attendance” at her benefit night performance. This sort of manipulation of national and gender identities in print, by both critics and performers, becomes an increasingly typical part of early republican fame.

Questions of nationality and gender also surround the better-known men of the early republican theater. Among the many hotly contested questions of the first decade of the post-revolutionary theater, for instance, were whether the character of Bagatelle, a randy, foppish French hairdresser in John O’Keefe’s popular ballad opera The Poor Soldier qualified as a gentleman or not, and whether his character was an insult to the manhood of America’s French allies. Likewise, the appearance of Mrs. Harper on the New York stage in the Augustan British comedy The Recruiting Officer, which included her cross-dressed heroine performing the army’s manual exercise for small arms, set off a tempest in a teapot in New York in 1787. The Amazonian performance did elicit an ironic offer from one critic of a commission in the state militia since, they suggested, the state too often handed out commissions to “beardless petites maîtres” with political connections, whereas Mrs. Harper’s shocking performance had, at least, been technically proficient. Having been busy reinventing themselves as classical republican patriarchs, some of the theater-going men of the early republic apparently found that the public display of masculinity, especially onstage, is a surprisingly fragile thing. American republican manhood, it seems, is always already under attack.

Such defensiveness seems ironic if we consider the gender associations of Thomas Wignell, the greatest self-promoting actor in the American theater before the advent of Cooper and the star system. Wignell is famously celebrated as the “Atlas of the American theatre” in one contemporary performance review, but he was a low comedian, not a tragic hero. If one examines the list of his post-revolutionary parts before his secession from the American Company, he plays mostly small supporting roles in tragedy. His biggest leading role is the madcap man-child Tony Lumpkin in Oliver Goldsmith’s comedy She Stoops To Conquer, a role requiring great reserves of energy and a natural talent for clowning that borders on the juvenile. His fame, moreover, rests on two parts that suggest anything but a reassuring vision of masculinity.

Wignell is most famous for his performance as the cowardly Irishman Darby from O’Keefe’s ballad operas The Poor Soldier and Love in A Camp. Darby, first in his home village and then in a Prussian military camp, distinguishes himself through sheer cowardice and incompetence in military affairs. He is terrified of combat and in Love in A Camp falls asleep at his duty post and is beaten, all the while loudly lamenting that he ever sold his farm to purchase a military commission. Wignell’s second famous role is that of Jonathan, the original stage Yankee, from Royall Tyler’s The Contrast. The American Company staged this play at New York in 1787, during a period when Tyler was in the city on business as an envoy for Massachusetts attempting to track down fugitives from Shays Rebellion. In this romantic comedy of manners that clearly owes a debt to the plays of Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Tyler sets loose upon an anglophilic New York full of fops and belles his two homespun New England patriots, the heroic republican Colonel Henry Manly and Manly’s excitable farmboy manservant, Jonathan. Jonathan, however, for all his patriotic fervor, was left at home by his father and brothers to tend the farm and take care of his mother during the war. His poor education, moreover, makes him more a parody than a reflection of his cultured employer, a philosophy-prone combat veteran who duels, literally and figuratively, throughout the play with Tyler’s foppish New Yorker villain, Billy Dimple.

Jonathan begat the stage Yankee, a line of business that would sustain itself on the American stage until well into the nineteenth century. The popularity of the character, however, seems to have been the result of a felicitous interaction between the role and the performer. A short, stocky man with red hair, Wignell clearly stood out on the stage, and he took advantage of the singularities of his appearance in marketing himself. Indeed, Wignell’s stage presence and his looks even invaded Tyler’s script, attributing an aura to the actor even on the page. The Contrast‘s most famous scene is a lengthy meta-theatrical joke where Jonathan decides to do a bit of sightseeing in his spare time; he unintentionally goes to the playhouse, which he, like so many other newbies in the history of meta-theatrical humor, does not realize is a world of illusion. While there, Jonathan, played by Wignell, encounters that other famous Wignell character “Darby Wag-All,” a “cute, round-faced little fellow with red hair, like me.” Wignell thus simultaneously embodies the salt-of-the-earth republican patriot, the Yankee’s cowardly Irish mirror image, and the metropolitan-born performer capable of hoodwinking Jonathan through theatrical illusion. Wignell’s famous performances and his odd looks hold a funhouse mirror up to the ideal self-image of early republican manhood, but his audiences seem to like what they see in both his features and his comic capers.

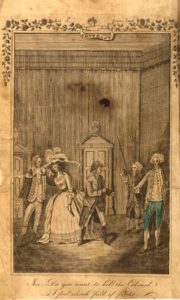

Wignell, to whom Tyler gave the copyright for his play, took advantage of both the role of Jonathan and his own features when he published The Contrast in Philadelphia in 1790, a year before he quit the American Company and began his own theater there. This self-promotion is evident in the edition’s frontispiece engraving, based on a drawing by William Dunlap (who also wrote a short ballad opera, Darby’s Return, for Wignell). Dunlap takes as his subject the climactic scene of the fifth act. Colonel Manly has rescued his citified sister, Charlotte, from being sexually assaulted by Billy Dimple, and the two men are on the verge of dueling. Jonathan has rushed in to “save” Colonel Manly. Jonathan, who hardly speaks in the scene, is clearly center stage, and the print is framed with his lines, “Do you want to kill the Colonel? I feel chock full of fight!” Although he has failed as both a lover and a fighter in the play up to this point, Jonathan’s masculinity seems to be redeemed here, even though his presence is utterly superfluous to the action of the scene and Manly quickly calls him off. Wignell, with a material interest in a play which, although he made it famous, was only performed about half a dozen times before it faded out of repertory, seems to be marketing himself as much as Tyler’s play with the inclusion of this scene engraving, a feature that as I noted earlier was increasingly common for playbooks in the eighteenth century. A British-born comedian who was according to legend fresh off the boat and sitting in a barber’s chair when he learned that Congress had banned theater in the colonies, Wignell markets himself in print to his new country as the All-American Boy.

The evolution of celebrity in the early American theater was a complex process with its roots in the immigration of white Europeans to North America and its top branches in the exportation of the images of famous American performers back out again to the rest of our global village. While the star system that evolved in the early republican period lacked the ubiquity and superabundance of celebrity that the current structure of the entertainment industry provides to the consumer, the connections for both performer and audience are nonetheless evident in the historical record. Big-budget theatrical and film production in our world share their inherent risk and unpredictability with a colonial theater that began with a few adventurous artists crossing the Atlantic. Perhaps most importantly, whether for an eighteenth-century or a twenty-first century playgoer, the intersection of audience and performer constructs a sense of communal belonging, even if it is only belonging to a community of two people consisting of the star and the starstruck.

Further reading

Odai Johnson, Absence and Memory in Colonial American Theatre: Fiorelli’s Plaster (New York, 2006); Olive Logan, The Mimic World and Public Exhibitions: Their History, Their Morals, and Effects (Philadelphia, 1871); Trish Loughran, The Republic in Print: Print Culture and the Age of U.S. Nation Building, 1770-1870 (New York, 2007); Julie Stone Peters, Theatre of the Book, 1480-1880 (Oxford, 200); Wendy Wick Reaves, George Washington, an American Icon: The Eighteenth-century Graphic Portraits (Washington, DC, 1982); Susanna Haswell Rowson, Slaves in Algiers (Philadelphia, 1794); Jason Shaffer, Performing Patriotism: National Identity in the Colonial and Revolutionary American Theatre (Philadelphia, 2007); Royall Tyler, The Contrast: A Comedy in Five Acts (Philadelphia, 1790).

For more on the history of celebrity, see Daniel Boorstin, The Image; Or, What Happened to the American Dream (New York, 1962); Leo Braudy, The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History (New York, 1986); Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment (New York, 1972); Joseph Roach, IT (Ann Arbor, 2007); Chris Rojek, Celebrity (London, 2001).

For a general history of early American theater, see Don B. Wilmeth and Christopher Bigsby, eds., The Cambridge History of American Theatre, Volume I (New York, 1998). For more on Thomas Wignell and the role of Darby, see Jeffrey H. Richards, Drama, Theatre, and Identity in the American New Republic (Cambridge, 2005). For more on Edwin Forrest, see Richard Moody, Edwin Forrest: First Star of the American Stage (1960, New York). For more on Olive Logan and on the working conditions and public image of American actresses in the nineteenth century, see Claudia D. Johnson, American Actress (Chicago, 1984).

This article originally appeared in issue 10.2 (January, 2010).

Jason Shaffer is Associate Professor of English at the United States Naval Academy. His book, Performing Patriotism: National Identity in the Colonial and Revolutionary American Theater (University of Pennsylvania, 2007) was the Honorable Mention for the Barnard Hewitt Award in Theatre Studies from the American Society for Theatre Research and a CHOICE Magazine Outstanding Academic Title. He is currently working on a history of celebrity in the theater of the early republic.