Victorian Flower Power

America’s floral women in the nineteenth century

In the introduction to her Familiar Lectures on Botany, first published in 1829, Almira Hart Lincoln Phelps explained that “the study of Botany seems peculiarly adapted to females; the objects of its investigation are beautiful and delicate; its pursuit leading to exercise in the open air is conducive to health and cheerfulness. Botany is not a sedentary study which can be acquired in the library; but the objects of the science are scattered over the surface of the earth, along the banks of the winding brooks, on the borders of precipices, the sides of mountains, and the depths of the forest.” Phelps’s progression from gendered limitations (women, like flowers, should be “beautiful and delicate”) to limitless exploration (of the earth, brooks, precipices, mountains, and forest) echoes a more general development in nineteenth-century American women’s culture.

That familiar story follows middle-class American women as they emerge from the parlor onto the public stage to condemn slavery, to defend the indigent and the sick, and to fight for their own citizenship. From “beautiful and delicate” objects, they emerge as active agents of America’s social maturation. As this story goes, the delicate domestic woman exists as a kind of counterpoise to the strong public man. The two revolve around each other in a kind of codependent orbit, neither able to exist without the other but both strangely at odds. This neat bipolar world of the domestic and the public, the feminine and the masculine, served nineteenth-century middle-class men as they struggled to maintain their own authority in the face of all sorts of challenges to that authority. As women, working-class men, people of African descent, and others excluded from citizenship struggled to expand the bounds of citizenship, conservative moralists and their middle-class male supporters struggled to defend the status quo. To this end, the idea of separate spheres was perhaps the defining social ideal of Victorian America. There was the public world, and it was a place of strength and masculinity. And there was the private, domestic world—a place of delicacy and beauty. For a woman to leave the latter for the former was, implicitly, for her to sacrifice certain virtues ascribed to her gender—or so the words of Victorian men and women would have us believe.

Historical reality turns out, not surprisingly, to have been somewhat more complicated. The neat separation of feminine and masculine spheres existed more as an ideal than as a fact. As Phelps suggests, it was perfectly possible for a nineteenth-century American woman to define herself in terms that transcended contemporary gender norms. Curiously, one of the arenas in which women did this involved flowers, nature’s most stereotypically feminine production. The connection between women and flowers seems so obvious—and stereotypical—that its significance is often overlooked or dismissed. Yet America’s early “floral women” reveal that their passions for flowers and their passions for public good were inseparable. Flower power nineteenth-century style may have reflected the “turn on, tune in” ethos of the better known era of flower power. But the “drop out” part was definitely stuff of a later and very different age.

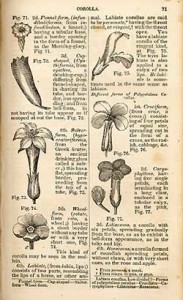

We might begin with Almira Phelps herself. She wrote books on botany, chemistry, and the physical sciences. Her Familiar Lectures on Botany and its companion for younger learners, Botany for Beginners, went through multiple editions throughout the nineteenth century: an 1891 edition of Botany for Beginners boasted of being the “270th thousand” one printed, and Familiar Lectures on Botany remained in print for more than four decades. By contrast, Amos Eaton’s widely-used Manual of Botany went through only seven editions between 1819 and 1836. In addition to writing science textbooks, Phelps was also a social reformer. As her Lectures on Botany suggest, she was especially interested in women’s education. Her assertions about the benefits of botanical study included not only healthful exercise and mental discipline but also loftier benefits. In a preface “To Teachers” in the 1848 edition of the Familiar Lectures, she noted that flowers “are designed, not merely to delight by their fragrance, color, and form, but to illustrate the most logical divisions of Science, the deepest principles of Physiology, and the goodness of God.” It was as if she were telling her readers, “Do not be deceived by the prettiness of flowers. Beneath their delightful surfaces lie profound lessons about the design of the natural world.” But for women to grasp those lessons, Phelps intoned, they would have to forgo their ephemeral scrapbooks and personal diaries for more scientific productions: “herbariums and books of impressions of plants, drawings, &c. show the taste and knowledge of those who execute them.”

Later editions of Familiar Lectures on Botany included a section on the “Symbolical Language of Flowers.” Dating at least to Shakespeare’s time in the West and even earlier in Asia, the language of flowers was an elaborate symbology in which specific flower species had particular emblematic meanings, as in Ophelia’s well-known line in Hamlet, “there’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance.” Flower emblems reflected both positive and negative traits, especially those particular to personal relationships: forget-me-not means “true love,” but foxglove means “insincerity”; heliotrope means “devotion,” but wild honeysuckle means “inconstancy,” and so on.

By the mid-nineteenth century, scores of flower language books had been published in the United States. Often, brief versions of this language were appended to other types of books, including botany textbooks (as in Phelps’s Familiar Lectures), plant guides, gardening books, and even conduct manuals. Books devoted entirely to the language of flowers, however, have their own particular charm. Some were published as token books, fitting neatly in the palm of a woman’s smaller hand; others were larger editions with elaborate gold-stamped covers that featured lavish full-color plates illustrating meaning-laden bouquets of multiple flowers. A number were specifically intended for prominent display on the parlor table. Most of them included both scientific information and sentimental material, often in the form of poetry.

Sarah Josepha Hale’s Flora’s Interpreter: or, the American Book of Flowers and Sentiments relied on several earlier works for its contents: Flora’s Dictionary (1829) by Elizabeth Wirt (wife of Attorney General William Wirt) and The Garland of Flora (1829) by Dorothea Dix (better known as the champion of dedicated asylums for the mentally ill). Whereas both Wirt and Dix published their flower-language books anonymously, Hale proudly claimed hers. First published in 1833, Flora’s Interpreter came at a time when Hale was still editing the American Ladies’ Magazine. In her introduction, Hale notes that the collection is an “experiment” that will “give an increased interest to botanical researches among young people.” But beyond that benign purpose lies a more potent one. From Hale’s pen, the language of flowers becomes a national language. Many of the flowers in her book reveal distinctly “American sentiments,” which are in turn reinforced by copious excerpts from American poets. For, she asserts, “it is time our people should express their own feelings in the sentiments and idioms of America.”

When many American writers were preoccupied with defining and celebrating American productions, Hale’s nationalism is not unique within the genre of flower language books. Dorothea Dix, in the preface to The Garland of Flora, hopes that her book will “display many pleasing traits of national manners.” Lucy Hooper, in the preface to The Lady’s Book of Flowers and Poetry (New York, 1859), similarly expresses “pride and pleasure” regarding “the selections from our own native poets.” Poems by Lydia Sigourney, Frances Osgood, Sarah Helen Whitman, and Hannah F. Gould stand beside those by Emerson, Whittier, Longfellow, and Holmes in these American flower books.

As the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book from 1837 to 1877, Hale wielded enormous power through her writings, especially her editorials. She promoted the study of botany and urged her readers to cultivate an interest in flowers, especially wild flowers. In July 1841, Godey’s Lady’s Book asserted that the preservation of wild flowers is “a subject worthy the attention of our sex” and noted the benefits of this activity as “a pleasing exercise for the mind.” The article further discussed the potential for women’s contributions to the larger project of native species preservation: “If memoranda were made of the places where such wild flowers are found, the latitude, with the common name, and whether they grow singly or in groups, profusely or sparsely, with the time of flowering, ladies might add something to the history of our Flora worthy of remembrance, and particularly so, would they make themselves acquainted with, and note their botanical characteristics.” Even more significantly, the author (most likely Hale) pointed to such activity as an example of women’s civic involvement. Their botanizing efforts, the author suggested, would save America’s floral treasures from the relentless march of cultivation:

“Our American woodlands are rich in the treasures of the florist and botanist. It is to be feared, however, that the hand of the early cultivators of the soil, has swept for ever from the face of nature many of the brightest gems of the forest and the plain . . . The most beautiful and delicate wild flowers known to our older states, generally inhabit the depth of the forests, the skirts of woodlands, the mountain fastnesses, or the rocky and precipitous banks of rivers and creeks. And why? Because our extensively cultivated lands, have been laid under tribute for bread; and the remorseless plough, sacrificing to the first instincts of nature all that could captivate the eye of the florist, has left only to the fringe of our worm fences and the edges of our highways, generally speaking, the coarser productions of the soil . . . The diminishing and fading wild flowers of our land call to [us] for protection.”

In an interesting reversal of gender roles, women have become the protectors of the more delicate and vulnerable wild flowers, these “gem”-like treasures of forest, plain, and wilderness. Although most historians place the beginnings of American women’s conservationist consciousness and activism in the late nineteenth century, this example from the 1841 Godey’s Lady’s Book suggests that this emerged much earlier.

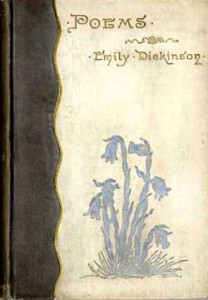

The popularity of botany, flower collection, and herbarium construction can be traced not only through such mentions in the popular press but also in women’s private writings. In May 1845, the fourteen-year-old Emily Dickinson wrote to her friend Abiah Root, “I am going to send you a little geranium leaf in this letter which you must press for me. Have you made you an herbarium yet? I hope you will if you have not, it would be such a treasure to you; ‘most all the girls are making one. If you do, perhaps I can make some additions to it from flowers growing around here.” Although famous today as one of America’s foremost poets and a significant precursor of the modernist aesthetic, Dickinson was probably best known during her own lifetime as a gardener. Her love of flowers came early, as this letter attests, and like “‘most all the girls” of her day, Emily was preserving local species in an herbarium. Flowers, both cultivated and wild, figure prominently in her poetry: cardinal flower, clover, daisy, dandelion, gentian, harebell, heart’s ease, jessamine, orchis, and rose are but a few of those she specifically names. The image of an Indian pipe, one of her favorite flowers, adorns the cover of the first edition of her posthumously published Poems.

The symbolic power of flowers attracted other women writers in the nineteenth century. Louisa May Alcott’s first book was Flower Fables, published in 1854 but written several years earlier for Ellen Emerson, the daughter of Ralph Waldo Emerson. In these moralistic tales, personified flowers teach virtues such as unselfish love, care for the poor, patience, cheerfulness, and humility. After the Civil War, the prolific African American poet, essayist, and lecturer Frances Ellen Watkins Harper used the flower fable format to promote a message of racial tolerance. In “The Mission of the Flowers,” published in the Harper’s collection Moses: A Story of the Nile (Philadelphia, 1869), the beautiful rose is the center of attention, and “its earth mission was a blessing,” whether cheering the sick or brightening a prisoner’s cell. The rose, “very kind and generous hearted,” “wished that every flower could only be a rose.” A spirit grants her wish, and she changes every flower in the garden into a rose. But soon “that once beautiful garden was overrun with roses; . . . that variety which had lent it so much beauty was gone, and men grew tired of roses, for they were everywhere.” The rose realizes the error of her ways, wakes to find that she was only dreaming, and learns a powerful lesson: “to respect the individuality of her sister flowers.” Of various shapes, colors, sizes, and blooming seasons, each flower has its own valuable mission; “and of those whose mission she did not understand, she wisely concluded there must be some object in their creation.” Harper had a strong sense of her own mission as an abolitionist and a champion of equality for women and African Americans; as an activist who also felt the prejudice of her white sister feminists, she deeply understood the need for the movement’s metaphorical gardens to feature more than just roses.

Not all floral women had careers as public as Sarah J. Hale or Frances E. W. Harper. One woman whose accomplishments were known to just a small group of experts during her lifetime is now memorialized with several species of wildflowers from the intermountain region of the western United States. Thompson’s Dalea (Psorothamnus thompsoniae), Thompson’s Penstemon (Penstemon thompsoniae), and Thompson’s Woolly Locoweed (Astralagus mollissimum var. thompsoniae) are all named for their discoverer, Ellen Powell Thompson. The wife of Professor Almon Harris (“Harry”) Thompson and the sister of Major John Wesley Powell, Ellen Thompson accompanied her husband, brother, and other members of the second exploratory expedition of the Colorado River through the canyon country of southern Utah and northern Arizona. Harry Thompson was Powell’s geographer and chief assistant, and “Nell” Thompson was widely admired by the other explorers for her cheerfulness, “love of adventure,” and botanical interests. Ellen Thompson kept a diary in 1872, which covers her plant collecting as well as daily life in camp.

Excerpts from her diary reveal not only her fascination with local flora but also the extraordinarily difficult conditions in which she did her botanizing. On March 6 she wrote, “we are in a heavy snow storm for four hours, tho we stop several times to sketch. Found a new cactus (to us). Intend to secure the blossom if possible.” During the next several weeks, she was sick more often than not, frequently not able to get out of bed or do more than read or write a few letters or do some mending. Yet she persevered, insisting on proper botanical procedures even when she could not collect specimens for herself. On March 29 she wrote in her diary that “Jones brought me three flowers, but do not make out what they are as he brought no leaves.” A few days later, she noted that “we woke this morning to find that snow had fallen to the depth of 2 feet during the night. Not too comfortable . . . to be up on the mountains in such a storm with nothing for a cover but a small tent. Have worked with my plants all day.”

Thompson’s work remains important to botanists, for the new species she discovered and for the many other species that she successfully identified and preserved. Her herbarium specimens are among the earliest scientific record of Utah flora. Just as important, however, is the larger narrative told in the sparse detail of her diary and the more detailed accounts of those whose work received greater recognition at the time. Hers is the story of a middle-class, college-educated woman who did not stay at home to raise children and keep house. Instead, she joined her husband on a fascinating and challenging journey into unfamiliar territory and made the most of her time there, using her intellect, education, and interests to contribute valuable scientific information to the overall effort of the expedition.

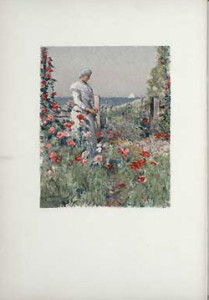

In the decades after the Civil War, as the western part of the country opened to exploration and settlement, regional differences became a source of national pride rather than the impetus for armed sectional conflict. Writers of the “Local Color” movement paid careful attention to dialects, folklore, landscapes, and manners, producing a regionalist literature in both fiction and nonfiction. In New England, the work of Celia Laighton Thaxter often described the Isles of Shoals, a collection of small, rocky islands off the New Hampshire coast. Thaxter moved to one of these islands at age four, when her father became the lighthouse keeper of White Island. Nearly sixty years later, having spent most of her life on and around these islands, she published An Island Garden, a memoir about her many years of experience as a gardener. In beautifully detailed prose infused with a passion for nature and a wonderful sense of humor, Thaxter invites readers to notice, as she does, the changing of seasons, the birds and insects that threaten and sustain her plants, and the flowers that “have been like dear friends to me, comforters, inspirers, powers to uplift and to cheer.”

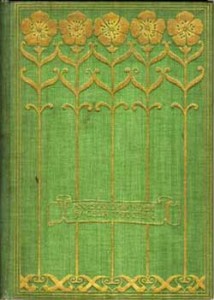

Published in 1894, An Island Garden featured color illustrations by Childe Hassam, the American impressionist artist who spent many summers at the Isles of Shoals, painting their rocky coastlines and wild hillsides. One of Hassam’s favorite subjects was Thaxter’s garden, and more than twenty of his illuminations and full-page scenes illustrate An Island Garden. Completing this treasure of late nineteenth-century textual and visual art is the exquisite cover design by Sarah Wyman Whitman. Whitman was one of the principal artist-designers for Houghton-Mifflin, and her Art Nouveau covers appear strikingly fresh today. Whitman’s predilection for floral motifs reveals the organicism of Art Nouveau, while her frequent use of soft-edged, ribbon-style banners hearkens back to the feminine ornament of an earlier generation.

The heyday of floral women came to an end with the close of the nineteenth century. Although women would continue to study botany and write about flowers throughout the twentieth century, their attentions were more often devoted to other concerns and pursuits. The modernist fascination with the machine age supplanted Victorians’ fascination with the natural world, and women’s professional opportunities outside the home increased in number and social respectability.

Looking back, the limitations of nineteenth-century American women’s culture seem in many ways to have enabled their widespread dedication to flowers. As an appropriately feminine form of science, botany literally opened doors for women, permitting them to step outside and ramble though the woods searching for specimens. But perhaps the most important “public” function of the collection, preservation, and artful display of flowers was conservation. The work of these botanizing women raised national consciousness about the need to save America’s vanishing native species.

Further Reading:

For more on women and science in early America, see Nina Baym, American Women of Letters and the Nineteenth-Century Sciences (New Brunswick, 2002). A useful survey of American women’s environmental involvement can be found in Vera Norwood, Made From This Earth: American Women and Nature (Chapel Hill, 1993). Judith Farr’s The Gardens of Emily Dickinson (Cambridge, Mass., 2004) gives rich detail about the poet’s love of flowers. The full text of Harper’s “The Mission of the Flowers” appears in Frances Smith Foster, ed., A Brighter Coming Day: A Frances Ellen Watkins Harper Reader (New York, 1990). The excerpts from Ellen Powell Thompson’s diary are from Beatrice Scheer Smith, “The 1872 Diary and Plant Collections of Ellen Powell Thompson,” Utah Historical Quarterly 62:2 (1994): 104-31. A facsimile edition of Alcott’s Flower Fables is available (Bedford, Mass., 2004), as is one of Thaxter’s An Island Garden (Boston, 2001).

This article originally appeared in issue 7.1 (October, 2006).

Annie Merrill Ingram is associate professor of English at Davidson College, where she teaches courses in American literature and environmental studies. She has recently coedited Coming into Contact: Explorations in Ecocritical Theory and Practice, forthcoming from the University of Georgia Press.