Viewpoints on the China Trade

A young nation looks to the Pacific

With their Revolution completed, their constitution written, their nation officially (if shakily) established, the self-styled “Americans” faced the world in a fundamentally altered posture. Throughout the preceding two centuries, they had been colonists, and thus, in a broad sense, dependents. They had absorbed from elsewhere regular infusions of migrants and goods, of cultural nourishment and guidance.

But henceforth the currents would flow, also, in reverse direction. The new United States would increasingly—sometimes aggressively—turn out toward other groups and places. It would proudly proclaim its republican credo as a “beacon of freedom” for political reformers around the world. It would proffer its “go-ahead” spirit as the key to social development. It would urge its highly charged version of Protestant Christianity on all sorts of “heathen” unbelievers. Moreover, its people would rapidly multiply their physical contacts with the rest of humankind. Especially after about 1800, their travel and commerce would extend, quite literally, to the farthest corners of the earth.

The acme—the epitome—of this remarkable outreach was the so-called China trade. To be sure, Americans were followers, not pioneers, here. Britons, Russians, and Spaniards (among others) had preceded them along the route to Cathay since at least the beginning of the eighteenth century. The Portuguese had claimed the island of Macao (just south of Canton) in 1557. And occasional Europeans had been voyaging that way—singly or in small groups—from far back in the Middle Ages. The American colonists, meanwhile, had been expressly forbidden by their imperial masters from joining in most forms of international exchange.

Yet once independence was achieved, American traders hastened to assert their own claims to what they called the Far East. And, after little more than a generation, they had gained for themselves a leading role. From Boston and Salem, Massachusetts; from Newport and Providence, in Rhode Island; from New York and Philadelphia and Baltimore, further south, the ships poured out—by the dozens, and then by the hundreds, each year. Canton was their chief, but far from their only, destination. For the China trade was just one piece of a still larger “East India” (Asian) connection. Calcutta, Madras, Sumatra, Batavia, Port Jackson, Manila: these places, too, figured heavily in the traders’ itinerary. The eventual outcome would include some astonishing individual fortunes, and a burst of capital formation to fuel the first phase of American industrial development.

Even within itself, the China trade was a complex, multisided, many-splendored thing . . .

It was a clutch of prosperous merchants gathered on summer afternoons in a massive, glass-domed structure called the Boston Exchange Coffee House, dressed in ruffled nankeen shirts, seated at finely turned mahogany-and-bamboo tables, sipping tea from china cups, exchanging choice bits of financial gossip, and looking out across the nearby harbor for the return of long-departed ships. (Some voyages lasted for as many as four years.)

It was twenty-odd Yankee farm-boys turned “tars,” the crew of a trim, three-masted schooner, becalmed in the midst of a glassy tropical sea, mending ropes and sails and nets, whittling scrimshaw figurines, catching sea turtles, counting the spouts of a passing whale, cursing the endless, windless horizon, and dreaming all the while of the “shares” they would one day carry home to stake a claim in their native countryside. (Most sailors in the China trade would make just a single voyage, and then return to work the land.)

It was a gang of sea-hardened hunters, young men bent on adventure, accepting of danger, set ashore for months at a stretch on a rock-rimmed beach along the outermost of the West Falkland Islands, deep in the lower Atlantic, methodically clubbing to death hundreds of bellowing fur seals, whose skins would then be scraped and dried on nearby pegging grounds prior to stowage en masse for shipment to the Orient. (Fur seals were taken from islands and atolls across a broad arc girdling the entire southern quadrant of the globe, including large sections of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Within a scant few decades, the hunt had rendered them nearly extinct, nearly everywhere.)

It was another group of Yankees, but this one a resident colony, and numbering in the hundreds, living as “alone men” on the Spanish-owned isle of Mas Afuera off the west coast of South America; huddled in dank wooden huts, with scruffy little vegetable plots set alongside; struggling against ceaseless storms, insects, and disease; drinking, gambling, fighting; and gathering their own stash of skins for the arrival of the next season’s trade fleet. (Mas Afuera was a seal-hunter’s El Dorado. It is estimated that three million skins were taken from this one little site before a Spanish naval squadron evicted the hunters, and burned their settlements, in 1805.)

It was yet another group, with another trading target, in another place: Fiji, far out in the south Pacific, where a transient population of foreign “beachcombers” mingled with native Islanders, in love and war and occasional rites of cannibalism, all to the end of securing the highly aromatic bundles of sandalwood that would later fetch huge sums on the Canton market. (The Chinese turned sandalwood into a fine powder which, for centuries, they had used as incense in elaborate religious and funerary ceremonies.)

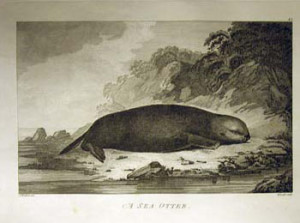

It was a wholesale assault on another ocean fur bearer, the charming, hapless sea otter, in the waters off the coast of present-day Alaska. And thus, too, it was a meeting-ground for white and native North Americans, the latter including Tlingit and Haida, Salish and Tsimshian, Nootka and Chinook, with their powerful warrior traditions; their water skills; their swift dugout canoes; their totem pole-fronted, stilt-raised villages; their potlatch and other complex cultural practices, all achieved within a productive system that did not (and could not) include agriculture. (The Northwest Coast would quickly become a vast adjunct to the China trade. Sea otter pelts, informally dubbed “soft gold,” were especially prized by merchants from the cold climes of north China; a fully loaded trade ship might thus expect triple, quadruple, or even better, returns on its investment.)

It was also, of course, Canton itself, the only Chinese port-of-entry open to foreigners. Here, at its eastern terminus, the trade was subject to elaborate regulation and protocol: gift exchanges; the engagement of pilots, interpreters, provisioners, and stevedores; the payment of taxes, duties, and outright bribes; the inspection and rating of all imported products (sea otters, for example, were divided into ten carefully delineated categories). There were dangers to avoid, ranging from Malayan pirates lurking outside the port entrance, to the sudden onset of Pacific typhoons, to local sharpers who packed shipping chests with wood chips or paper instead of tea and silks, to overindulgence in samshew, a potent Chinese whiskey. There were restrictions to obey, especially those that confined all fan kwae (foreign devils) to a narrow waterfront warren of streets and alleys set apart from the city proper. There was an intricate commercial system to master, with hoppos (customs superintendents) and cohong merchants (those formally licensed by the emperor), coolies (day laborers) and chinchew men (local shopkeepers), chops (official seals and marks) and hongs (warehouses). Finally, there were goods to buy and carry home—the point of it all—starting always with tea and silks, but also including nankeens (hand-loomed cotton fabrics), crepes, and grasscloth; porcelain tableware (china) of every conceivable description; lacquered furniture; elegant oil, watercolor, and reverse-glass paintings (portraits, landscapes, garden scenes); carvings in ivory, jade, and soapstone (chess sets, for example); sewing and snuff boxes in mother-of-pearl; silver flatware sets that mimicked Western styles; brightly painted hand-held fans of both screen and folding varieties (exported literally by the thousands, and considered de rigeur for genteel American ladies throughout the nineteenth century); elaborately filigreed tortoise-shell combs (also by the thousands, also wildly fashionable); umbrellas, window-shades, straw mats, wallpapers, feather dusters, horn apothecary spoons, and numerous other bits and pieces too humble to have been noticed in the surviving records. In short: a kaleidoscope of (what came to be known as) chinoiserie, on a scale bewildering to comprehend. (Virtually every middling household, in or near American cities of the period, would have had at least a few China-made objects. And in those with direct connections to the trade the total might easily rise into the hundreds. Moreover, tea was a beverage of choice for people of all classes.)

It was, even beyond the terminus, the various people who made these things in towns and villages stretched far across the interior of the Chinese mainland. Tea farmers in the eastern provinces above Canton who harvested the remarkably bountiful shrub three times a year, in dozens of varieties and grades. (Americans preferred green tea, especially the so-called Young Hyson, which came principally from Kiangsi and Chekiang). Also, merchants who brought the tea to market, mostly on rivers and streams in small, shallow-hulled junks. Also, silk-growers in the lower Yangtzee Valley who tended both the precious fiber-producing caterpillars (bombyx mori, the silkworm) and the equally essential caterpillar-sustaining mulberry trees. Also, painters, carvers, carpenters, silversmiths, porcelain workers, and other anonymous craftspeople whose handiwork would grace the homes—and lives—of strangers half a world away.

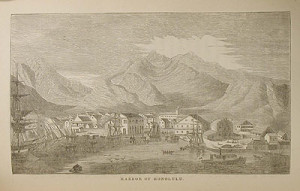

It was, perhaps most extravagantly, Hawaii. Set roughly in the middle of this entire web, and known then as the Sandwich Islands, the Hawaiian archipelago served as crossroads, as refitting and provisioning stop, as vacation spot, as pleasure garden, as commercial entrepôt, as hiring station, as escape hatch, and (beginning about 1820) as missionary target par excellence. Ships arrived from several directions—Sitka Bay, the coastal towns of Peru and Chile, other parts of Polynesia—reflecting the different segments of the China trade. Most stayed for intervals of from two weeks to two months before proceeding on across the Pacific. Officers, crew, and supercargoes alike described the islands in paradisiacal terms—”designed by Providence,” wrote an admiring visitor, “to become . . . a place for the rest and recreation of sailors, after their long and perilous navigations.” All praised “the genial climate, the luxurious abundance, and the gratifying pleasures” to be found there. All enjoyed the remarkable variety of fresh food and drink, especially pork (from the hogs that ran more or less wild onshore), fowl of several types, tropical fruits and vegetables (such as breadfruit and taro), and coconut (with its delicious milky contents). Most partook of the freely flowing liquor (in the form of locally distilled rum and gin). And—perhaps inevitably after the long months at sea—many sought the company of lissome wahines, native women described as wonderfully “complaisant” and “amorous.” (By one account, similar to many others, “[T]hey would almost use violence to force you into their embrace.” But, in fact, much of this activity was simple prostitution.)

It was, finally, a host of impressions—thoughts, feelings, wishes—that grew, and spread, and palpitated, in the hearts and heads of the innumerable throng whose lives it touched. Widened eyes, expanded horizons, a lifted gaze, a new sense of possibility and potency: thus its impact across the length and breadth of what was then called Young America.

For the China trade was indeed a key part of our national youth. “China,” wrote a pioneer sea captain who had seen for himself, “is the first for greatness, richness, and grandeur of any country ever known.” Might America grow someday to become the same?

Further Reading:

On various aspects of this topic, see Ernest R. May and John K. Fairbank, America’s China Trade in Historical Perspective (Cambridge, Mass., 1986); James Kirker, Adventures to China: Americans in the Southern Oceans, 1792-1812 (New York, 1970); and James R. Gibson, Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and China Goods (Montreal, 1992). For an overview, with emphasis on the material side including many forms of chinoiserie, see Carl Crossman, The China Trade (Princeton, 1972).

This article originally appeared in issue 5.2 (January, 2005).

John Demos, professor of history at Yale University, is the author most recently of Circles And Lines: The Shape of Life in Early America (Cambridge, Mass., 2004). This article is adapted from a book he is currently writing on nineteenth-century missionary work, to be entitled The Heathen School: A Story of Hope and Betrayal in the Age of the Early Republic.