Vive la Différence?

Le musée du quai Branly

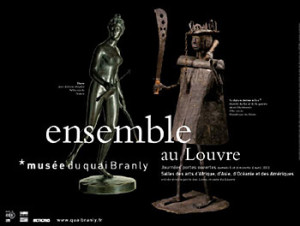

Inside every French statesman there’s an intellectual fighting—or, more likely, arguing—his way out. Should you have the time and disregard for global warming, buy a plane ticket and fly away to see a new museum in Paris that proves my point. The musée du quai Branly is dedicated to non-Western art. Every outgoing French leader has to have a monumental project and Quai Branly was Jacques Chirac’s—the French call it “le musée Chirac.” Yet the first thing you see upon entering the museum is the Theatre Claude Lévi-Strauss, named for the late patriarch of French structuralist anthropology. Imagine a little, theatrical Lévi-Strauss within a big, sprawling Chirac—two big egos managing somehow to coexist. The egos are, here, in the humble service of the people whom Lévi-Strauss claimed had a “savage mind,” one neither simpler nor lesser than the mind of civilized people, just different.

In fact, it would be fitting if the entire museum of Quai Branly were named after Lévi-Strauss. The place is a monument to French intellectual culture, that glittering amalgam of brilliance and belligerence, which may be why so many people react so strongly to it. You either submit to its grandly analytic vision of things or else you get all huffily empirical—who says this vision makes sense of everything? The Quai Branly’s grand vision is simply that non-Western artifacts must be treated as art, different from Western art but equal to it. Indeed, many of the new museum’s objects were once in the musée national des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie and in the musée de l’Homme, the latter of which had an exclusively ethnographic rationale, something the new museum shuns. The huffy empirics have duly responded: If all these things are art in the same way the stuff in the Louvre is art, why aren’t they in the Louvre, as Chirac had originally suggested they might be? Isn’t putting them in a separate museum slightly demeaning or even racist, in the manner of the old ethnographic museums that had assumed so-called primitive peoples were best explained by schemas specific to their lower level of social organization?

Strangely, the musée du quai Branly has been little discussed in the United States—I first heard about it from an Australian. (Members of Australia’s chattering classes love Quai Branly, imagining it as the equivalent of the museum of aboriginal art their country ought to have.) Yet Quai Branly’s collections of American Indian items are said to be superb, including even some items that Lévi-Strauss himself acquired. So while in Paris this October, I found the new building, wove my way through its lower gardens, queued up to buy a ticket, and then surrendered my ticket and submitted my bag for inspection at the inevitable security checkpoint. The ground floor beyond the security guards holds a temporary exhibition space, the theater, and the start of a broad spiral staircase. You make your way up the spiral slowly, as at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, though here you see only incidental placards and exhibits along the way.

The real exhibits are at the top. There, the museum’s collection of thirty-five hundred objects is grouped into areas designated for the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania. Each zone is separated from the next by irregularly shaped walls made of some kind of composite that looks like dried mud covered with pale, polished animal skins. The earthy partitions give the impression that each exhibit section is like the part of the earth whose peoples generated the art within.

I headed up to the American zone, which represents all parts of the Western Hemisphere, from the Arctic through the Amazon. In the hushed murmur that is the acceptable soundscape of the modern art museum, my fellow visitors and I admired paintings on animal hide, headdresses made of brilliantly colored feathers, figurative pottery, moccasins, Kachina dolls, and wampum belts. It’s quite a collection and well worth visiting, though more for the items themselves than for the way in which they are presented.

In the art museums after which the creators of the museé du quai Branley have modeled their exhibition space, each painting or sculpture has a terse item label: artist’s name (with birth and death dates), title of work (and the date of its creation or exhibition), media used in the work, inventory number that identifies the piece of art. If you want more information, you’re welcome to consult the chattier labels on the walls (which often introduce an exhibit or section) or on the cases—where groups of similar items might be interpreted at greater length than an item label allows. That’s essentially what you see here: the item labels are terse (name of artist’s ethnic group, time when item was created, inventory number), and the wall or case labels offer an idea or two for the visitor to consider.

I could see the point, yet wished there were also a button on each case, helpfully labeled “pour l’académician ennuyeux,” which would light up some hidden text that offered more information on individual items for us tedious pedants. When, exactly, had that Great Lakes wampum belt made its way into French hands? Was it presented as a gift by some Native sachem back when the French were still in North America? Or was it collected much later? When and why? I had the same questions about many items, and I didn’t see why answers to such questions would undermine the emphasis on these objects as art. Museum labels sometimes do indicate the person who originally commissioned or bought a work of art, as well as information about the object’s subsequent peregrinations. Given recent controversies over the shady provenance of many works of art, from classical antiquities to Nazi loot, publishing such details might not be a bad idea. (But given UNESCO uncertainty over the issue of repatriation of non-Western objects from Western museums, perhaps members of Quai Branly’s staff have chosen a discreet silence.)

If the case and wall labels at art museums might include some straightforward historical or aesthetic information (such as the sorts of materials or techniques used in making the art), those in Quai Branly’s American zone favored anthropological discussion. Here again, it is evident that the museum’s intellectual patron saint is Lévi-Strauss and that at least some of its curators wish to display, alongside the native artifacts, French erudition, particularly of the structuralist variety.

The structuralists in anthropology took their name from linguists who had argued that the meanings of individual words mattered less than the overall patterns or structures they formed. Hand, God, and eye are not terms that simply designate obvious objects or concepts; these words have significance only in the context of their actual use—”the hand of God,” for instance, or “the eye of the beholder.” Ethnographers similarly sought the deeper structures within which everyday cultural acts existed. Lévi-Strauss interpreted kinship in this way: mother and grandnephew are meaningful terms only because they exist within a broader web of significant social connections.

Lévi-Strauss used his fieldwork in the Americas, principally Brazil, to offer a structuralist analysis of Native Americans, specifically, and of so-called savage people generally. He concluded that ceremonies, objects, and social roles throughout the Americas were fundamentally similar. What underlay such similarities, he believed, were distant, primordial patterns of cultural formation. Quai Branly follows his example by showing American Indian axes or clubs as physically and functionally related, wherever they came from. The old stereotype of all American peoples attired in feathers is also on vivid display at Quai Branly. Rather than question this Eurocentric belief, the curators show featherwork to be a fundamental and essential fact about Native American culture, whatever in the world that is.

Labels at museums for modern European art, however, make no such claims. If someone interpreted that art as manifesting an underlying structure that connects Fra Angelico to Picasso (or Rembrandt to Kiki Smith), art historians would surely protest that this cultural analysis oversimplifies things considerably—it could be a starting point but not the only point that museum visitors should take away.

Another case label at Quai Branly announced important similarities among gender roles throughout the Americas. Because Indian women gave birth to human beings, I read, they were more likely than Indian men to create objects that represented the human form—figurative art was innately female. I can’t argue with the premise, but the conclusion is arguable. In fact, feminists who do not agree with the theories of innate différence between men and women, as articulated by French intellectuals, argue against such conclusions all the time. It’s a bit much that Quai Branly’s curators present this interpretation as information, something that French schoolchildren who visit the museum, for instance, should accept without question.

I was finally reaching the end of the museum’s section on the Americas. O brave new world that has such people in it. The final cases contained items that looked African. They were. They were examples of art that people of African descent had created in the Americas. Placing them in the Americas section was an interesting idea—migration and creolization were, after all, highly significant to the history of the post-Columbian new world. But Africans weren’t the only migrants and creoles. Why not include some examples of objects that people of European descent had created in the Americas? If such items were instead kept in museums devoted to the art of Europe, why not put the African American items in Quai Branly’s section devoted to the art of Africa?

Every museum has—must have—some unstated rules of inclusion, organization, and interpretation. But the musée du quai Branly’s rules seemed designed to undermine its own premises. Why use ethnographic theories rarely if ever found in art museums? Why not instead deploy the kind of aesthetic criticism found in art museums? And why segregate non-Western and Western forms of art? Some of the museum’s other sections don’t have the strongly structuralist interpretation that I found in the Americas section—Asia is more complicated, it seems (too civilized to have a savage mind?), though Africa is not.

The museum is nevertheless difficult to summarize because it is so vast. The American section is in fact one of the smallest. And Quai Branly has enviable storehouses of artifacts. Behind the permanent collection are four scholarly collections: a textiles collection (over twenty-five thousand items), an enormous photographic collection (seven hundred thousand items), a musicology collection (ninety-five hundred items, some of which are displayed in a central glass tower), and a historical heritage unit (ten thousand items, including dioramas, travelers’ journals, and some of Paul Gauguin’s drawings from his Pacific sojourns). Multimedia displays integrate some of the photographs with artifacts and others play recordings of the musical instruments.

From the fourth scholarly collection, the historical unit, some of the museum’s curators have organized a temporary exhibit, “D’un Regard l’Autre,” or “Regarding the Other.” It asks visitors to consider how Europeans have considered the peoples of Africa, America, and Oceania (though not Asia), and it does so by itself regarding that process as historical. The exhibit begins in a darkened room with an illuminated central case that contains a small, elaborate ship. Made in the sixteenth century, the ship contains a clock, the gears of which play music and make the ship and its parts move (tiny trumpeters lift their instruments to their lips as the music plays). The whole thing is gilded and glows in its case. Its presence at the start of the exhibit brilliantly summarizes the historical processes by which Europeans developed the technical expertise (and lust for gold) that would carry them outward to the wider world.

The rest of the exhibition traces the subsequent history of European exploration and shows that European theories about other peoples have never been impartial.. It begins with the prehistory, the medieval European ways of representing “wild” peoples (as naked, hairy, club-wielding, animal-charming, and so on). Then it moves on to European representations of non-European peoples. The exhibit’s stunning centerpiece is formed by Albert Eckhout’s tall oil paintings of the different peoples of Brazil, done in the early part of the seventeenth century. (The most famous is probably the painting of the native woman, with her child, whose basket contains human body parts.) From there, the exhibit analyzes European engagement with worlds so new to them, from Bougainville’s historic exploration of the Pacific to modern travel and ethnography. Interesting motifs are European attitudes toward the natural world and Europeans’ tendency to classify non-Europeans as yet other parts of nature.

In short, the temporary exhibition does what the permanent exhibits upstairs do not: it shows that Europeans and non-Europeans have a common history, as well as distinctive cultures, and emphasizes that European attempts to classify non-Europeans are part of the story. The shared history makes the continued creation of separate museums for separate peoples questionable. Some of the things in the Louvre share a history with some of the things in Quai Branly. In the seventeenth century, Iroquois artists made wampum belts near or within New France (one result is at Quai Branly). One hundred years later, during a subsequent moment of French engagement in North America, eighteenth-century French sculptor Houdon made images of George Washington (one result is in the Louvre). These were not identical creations but they share a history, and it would be interesting to put them together in the same museum.

The musée du quai Branly had itself made this point, and made it at the Louvre, but had done so in yet another temporary exhibit—not as part of its permanent installation. And that exhibit’s emphasis seems to have been on similar forms or functions for Western and non-Western objects, not the shared history those objects might have had. But everything has a history, after all, even structuralist theory. When the musée du quai Branly’s exhibit labels for its American art begin to look dated, I wonder what will replace them?

This article originally appeared in issue 7.2 (January, 2007).

Joyce Chaplin is James Duncan Phillips Professor of Early American History at Harvard University and author, most recently, of The First Scientific American: Benjamin Franklin and the Pursuit of Genius. She is currently working on a history of circumnavigation.