Samson Occom’s Missionary Correspondence and the Common Pot

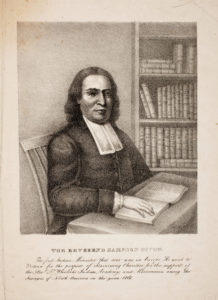

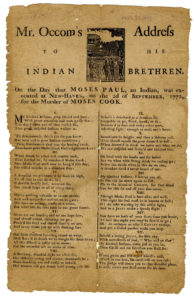

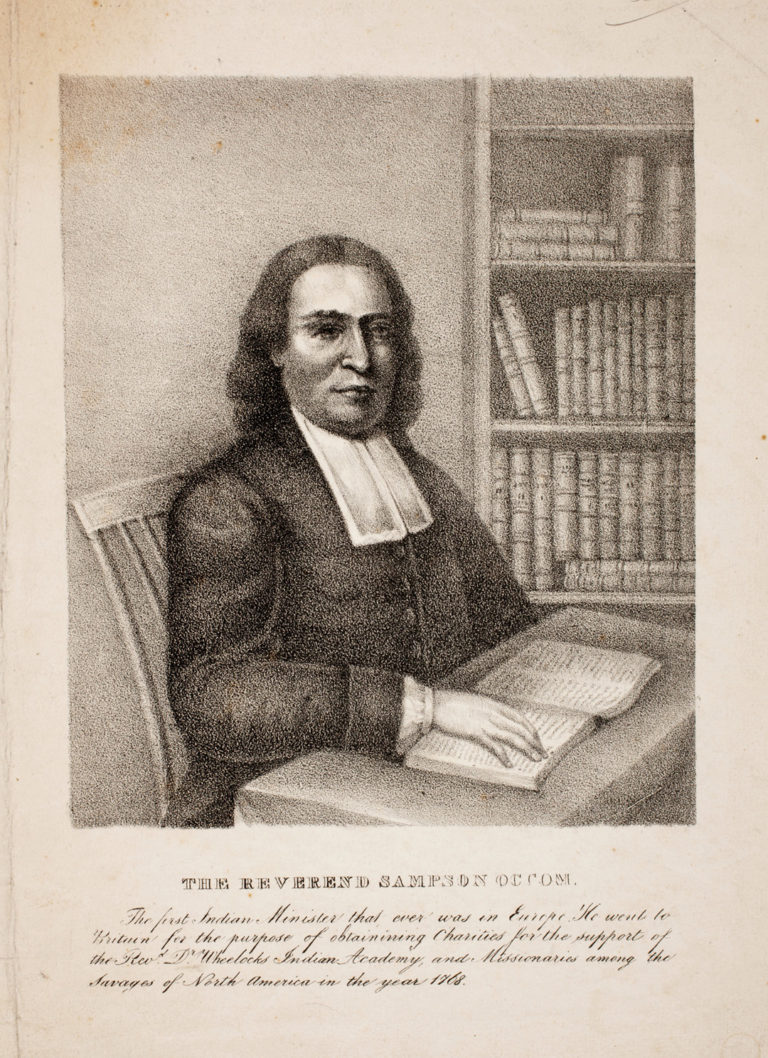

The Occom Circle at Dartmouth College presents a digital edition of 525 items related to the eighteenth-century Mohegan minister and advocate for indigenous rights Samson Occom. The website provides free access to these texts in the form of facsimiles accompanied by diplomatic and modernized transcriptions. The project includes prose works, letters, petitions, tribal documents, sermons, hymns, confessions, and journals composed by or relating to Occom.

The Occom Circle’s wide range of eighteenth-century genres provides a glimpse into Occom’s life and that of other eighteenth-century Native Americans. Confessions by American Indians like the narrative of Temperance Hannabal and drafts of Occom’s autobiography appear in the archives as well as rare eighteenth-century letters by American Indian women like Occom’s Montaukett wife, Mary Fowler Occom, Narragansett Sarah Simon and Mary Secutor, and Delaware Miriam Storrs. Occom’s student work and Hebrew textbook also give scholars a glimpse into the educational practices of eighteenth-century American Indian missions. Occom’s textbook includes marginalia and annotations such as “Samson Occom, an Indian of Moyauhegonnuek” and “Jure Hune Librum Tenet” or “this book holds the right” in Latin. Occom’s 1773 hymns “Come all my young companions, come” and “The Slow Traveller” deserve examination by scholars of early American poetry and religion. Of interest to book historians, lists of religious and instructional books also pepper the archive, such as the book list by Occom’s Montaukett brother-in-law David Fowler, who would later teach at Montauk and lead Brothertown.

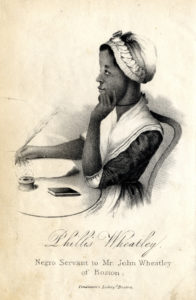

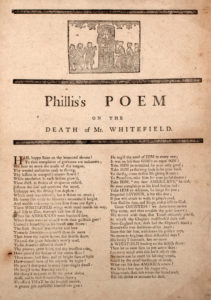

As these examples illustrate, The Occom Circle is also valuable because of its illumination of Occom’s missionary network. Occom’s letter to Susanna Wheatley, mistress of the famous African American poet Phillis Wheatley, demonstrates the interdependence of the literary and historical modes in early Native American writing. Additionally, the letter shares the indigenous ethos of what Lisa Brooks calls the “common pot,” that is, “whatever was given from the larger network of inhabitants had to be shared within the human community” in The Common Pot.

In a letter from Mohegan on March 5, 1771, Occom thanks Wheatley and hopes that her letter to John Thornton “will attract Bowels of Compassion towards me and mine.” The phrase “Bowels of Compassion” comes from 1 John 3:17 in the King James Bible: “But whoso hath this world’s good, and seeth his brother have need, and shutteth up his bowels of compassion from him, how dwelleth the love of God in him?” Thornton was treasurer of the English Trust that oversaw funds raised by Occom for Wheelock’s Indian Charity School. A strong supporter and friend to Occom, Thornton died one of the wealthiest men in England in 1790. With the reference to “Bowels of Compassion,” Occom prays that Thornton will share his wealth in a Christian version of the common pot, merging missionary networking with an indigenous Christian ethos.

Next, Occom broaches another problem, explaining that his family’s corn harvest last year was poor and meat scarce due to drought. He needs to buy food for his family but lacks the funds to do so, adding that his family burden has increased to “ten Souls” and constant visitors. Occom describes his house as “a Sort of an Asylum for Strangers both English and Indians, far and near.” In the spirit of the common pot, Occom welcomes strangers into his home despite their bad fortune, sharing what little they have.

Occom nevertheless recognizes that others are poorer than himself. He paints a picture of beggars wandering “almost Naked in the Severest weather…oblig’d to go from House to House, and from Door to Door, with Tears Streaming Down their Dirty Cheeks beging a Crum of Bread.” In comparison to these wandering poor, Occom praises God “Night and Day” for what he has been given, realizing, “I have no Room to open my Mouth in a way of Complaint.” The main body of the letter ends with a prayer that this letter “may find you and yours in Health of Body and Soul Prosperity.”

Occom’s postscripts contain the only straightforward requests in the letter. In the second postscript, Occom asks for “a Singing Book” for his children, while in the first postscript, Occom asks, “Pray madam, what harm woud it be to Send Phillis to her Native Country as a Female Preacher to her kindred, you know Quaker women are alow’d to preach, and why not others in an Extraordinary Case.” Occom advocates for Phillis Wheatley to preach to African Americans just as he has preached to American Indian people. Parallels between these two writers who traveled through the same eighteenth-century missionary circles have yet to be examined.

Digital editions of early American Indian writing are rare; in addition to The Occom Circle, the Yale Indian Papers Project offers free facsimiles of early American Indian writing, including letters by Occom and tribal petitions. These projects, as Occom’s letter demonstrates, reveal a vibrant world of eighteenth-century social relations in a missionary context that has yet to be appreciated. Creating a literary genealogy linking Occom and Wheatley could change conceptions of early American Indian and African American writing and missionary work.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.3 (Spring, 2017).

Lauren Grewe is a doctoral candidate in English at the University of Texas at Austin. Her dissertation, “Woven Alike with Meaning,” is on sovereignty and form in early Native North American poetry.