American Prophecies: African American News in the Antebellum Era

You suggest in the introduction that the African Americans who started newspapers in the nineteenth century did so because of their sense of “black chosenness.” Can you explain what you mean by that term?

“Black chosenness” is shorthand for the belief that African Americans are God’s chosen people. This belief gained purchase and power among black communities in the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and rests in a comparison between African Americans and the biblical Israelites, whom the Bible marks as God’s original chosen nation. The Bible records numerous instances where the Israelites suffer slavery and oppression. We’re perhaps most familiar with the period when the Egyptians enslaved the Israelites, which is recounted in the book of Exodus, but in later periods the Israelites were enslaved by the Assyrians and the Chaldeans, a civilization typically represented through its capital city of Babylon. African American preachers and writers repeatedly pointed out the obvious parallels between the Israelites in slavery and enslaved black people in the United States, and often argued that if black Americans were the modern manifestation of the biblical Israelites, then they too could claim the mantle of God’s chosen nation.

A faith in black chosenness often brought with it a sense of responsibility to act in a certain way (what I call “acting chosen”), though what exactly acting chosen meant in terms of on-the-ground behavior could change depending upon specific circumstances. But most importantly, perhaps, black chosenness contained within it a certainty that black Americans would eventually be free, since God would not allow his chosen people to remain in bondage forever. The when and how of freedom may have been uncertain, but black chosenness guarantees the fact of black liberation.

I don’t want to suggest, though, that black editors began their newspapers because of their faith in black chosenness. In each of my chapters, I try to flesh out in as much detail as possible the specific circumstances that led to the founding of particular newspapers. But black chosenness became a fundamental, if at times subtle, theme of the black newspapers that I take up in my book. Newspapers allowed black editors to apply their faith in black chosenness to specific circumstances, and those circumstances in turn affected the precise contours of black chosenness. For example, in 1848 Frederick Douglass and his staff used the North Star to explore the relationship between black chosenness and the anti-monarchical revolutions that rocked Europe during that year. And as it connected black chosenness to an international revolutionary movement, the North Star stretched the boundaries of the new chosen nation to include black and white revolutionaries located within and beyond the confines of the United States. As a medium in some ways designed to translate abstract ideas into concrete plans for action, the newspaper was an ideal way for black Americans to put the theory of black chosenness into practice.

How many newspapers were published by African Americans during the antebellum era? How did you decide to focus on the five you selected for the book?

I hesitate to even offer an estimate about the number of black newspapers published in the antebellum era. Frankie Hutton’s foundational book The Early Black Press in America lists seventeen “extant antebellum black newspapers,” but scholars continue to find references to papers that we have not yet recovered. For example, Thomas Hamilton is perhaps best known as the editor of the Weekly Anglo-African, a newspaper that I focus on in my book. But according to his contemporaries Hamilton also edited the People’s Press sometime in the 1840s, and I recently discovered references to a short-lived Tri-Weekly Anglo-African, also edited by Hamilton, that ran for a single week in 1865. Now, Thomas Hamilton was a well-known member of New York City’s black elite, and still we’re missing entire publications that he produced. So I have to imagine that there are also as-yet-unrecovered black newspapers published in small cities and towns across the northern United States that we don’t even know we’re supposed to be looking for. And if we decide to consider black newspapers published in Canada and the Caribbean (I think we should), the number grows even larger. All of which is to say, there is still an immense amount of work to be done recovering and analyzing early black newspapers, and I always intended my book to be an entry point into a vast archive, rather than a comprehensive study.

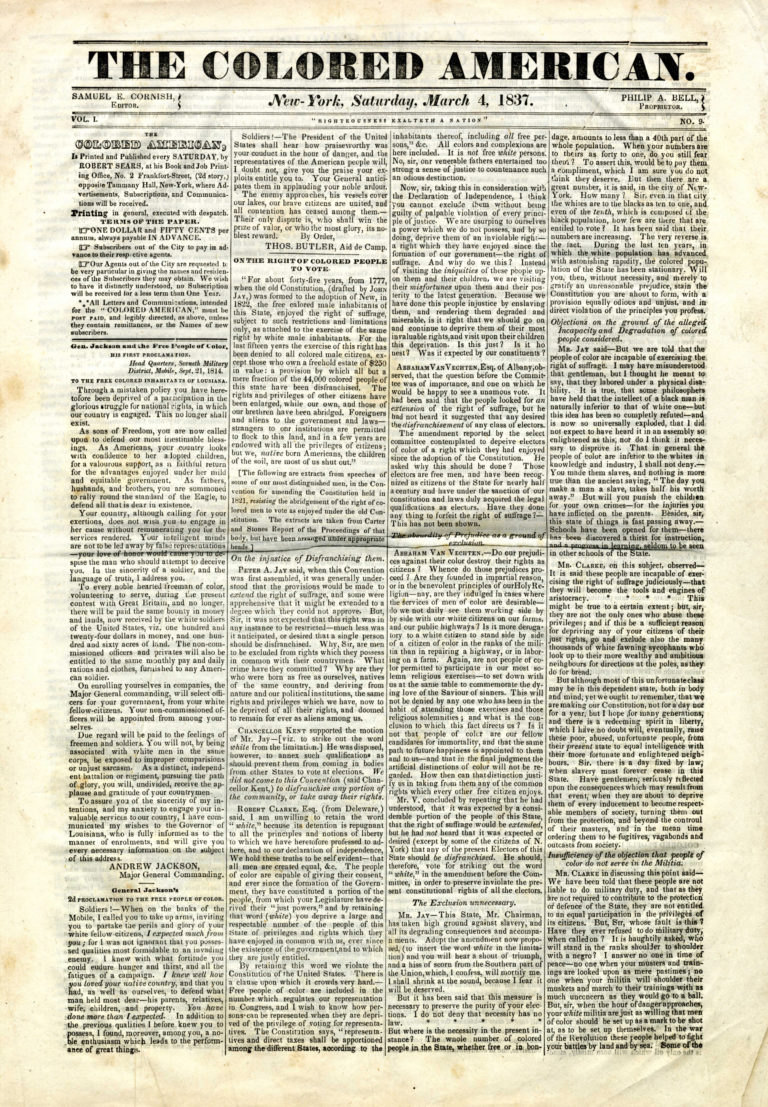

I decided to focus on the five newspapers in my book for practical as well as thematic reasons. I wanted to be able to write about newspapers with runs of at least a year, and as much as possible to be able to read each paper’s entire run. So when narrowing down my archive I was immediately confronted by problems of archiving and access. At the time I began my work on this book, only a single issue of newspapers like Martin Delany’s Mystery was extant, while multiple years of Frederick Douglass’ Paper were either missing or incredibly difficult to access. On the other hand, nearly full runs of Freedom’s Journal, The Colored American, the North Star, the Provincial Freeman, and the Weekly Anglo-African are all relatively easily accessible, either on microfilm or (for a select few) digitally.

But beyond such practical concerns I chose to write about these five newspapers together because the publications and the people who made them were intimately connected to one another. One reason I decided to focus on newspapers published over a relatively short time period (about forty years) and small geographic area (the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada) is that the women and men who made and sustained these papers knew one another personally. Thomas Hamilton’s father, for example, helped found Freedom’s Journal, a newspaper that profoundly influenced Philip Bell’s decision to start The Colored American (where the teenage Hamilton worked as a newspaper wrapper). John Dick, who printed and contributed numerous articles to the North Star, later emigrated to Canada and helped produce the Provincial Freeman, edited by Mary Ann Shadd. And Shadd’s good friend and neighbor Martin Delany had his novel Blake published in the Weekly Anglo-African. In addition, because the editors of the papers I selected engaged in numerous activities besides newspaper editing, they met and interacted with one another in a variety of venues. For example, Samuel Cornish, Philip Bell, Charles Ray, Frederick Douglass, Mary Ann Shadd, and Thomas and Robert Hamilton all attended Colored Conventions. Cornish and Bell served together on education committees in the 1830s, and Douglass and Ray argued over the need for a new black newspaper in the 1840s. And sometimes these cooperations and disagreements spilled over into the pages of their newspapers long after the conventions had closed. So I tried, as much as possible, to put these particular newspapers into conversation with one another precisely because the people reading and writing these papers were actually in conversation with one another. And reading the five newspapers I cover in my book together, I want to suggest, offers us a far richer sense of a community that existed in person and in print than we would get if we read any one of the papers in isolation. Some of the newspapers that I focus on have been written about by other scholars, in helpful and important ways, but there’s much more work to be done teasing out the collective and collaborative nature of the early black press, within and across individual papers. My hope is that my book offers one example of what that kind of work might look like.

Throughout the book, you note that the editors of these newspapers saw their publications as vehicles to regulate or channel the behavior of African Americans. Why did they believe that their newspapers would be a successful avenue to pursue that goal?

It may be impossible to overstate the importance of the newspaper in the nineteenth-century United States. As the era’s dominant form of media, I tend to think of the newspaper in the nineteenth century in relation to television in the twentieth or the Internet in the twenty-first. When conducting research for this book, I read through a number of travel accounts from European visitors to the United States, and without fail the authors expressed their astonishment at the sheer number of newspapers in the U.S., and the influence that these papers exerted over the populace. The most famous of these accounts is probably from Alexis de Tocqueville, who devotes an entire chapter of Democracy in America to the place of newspapers in the United States, and sees the newspaper as the key means to not only reach but also to influence a scattered citizenry. Contemporary scholars have debated whether or not the newspaper actually possessed that kind of power, but nineteenth-century advocates and critics of the newspaper alike believed that it did. This respect for the power of the newspaper helps explain why delegates to Colored Conventions spent so much time discussing not only the creation of black newspapers, but the need to support papers of, in the parlance of the day, high moral standing. The minutes of these conventions are dotted with delegates worrying about the influence that a “bad” paper could have on its readers, especially children, and urging families to subscribe to journals that would teach upright behavior.

For the black New Yorkers who founded Freedom’s Journal, the first black newspaper published in the United States, this faith in the power of the newspaper to shape the perceptions and behavior of its readers was based in personal experience. Freedom’s Journal was founded for a number of reasons, but one of them was to provide a means to counter the racist representations of African Americans that were rampant in New York’s white newspapers. And we see attempts to correct such misrepresentations present in all of the newspapers that I write about in my book, because these lies could have material consequences. Beyond contributing to and justifying the general discrimination that African Americans faced in the North, white editors could and did use the pages of their papers to stir up and organize mobs to attack black gatherings, parades, and businesses. This is not to dismiss or minimize the importance of other institutions like the church, or other forms of print like the pamphlet and book. But when someone in the nineteenth century wanted to get their message out, if they could, they started a newspaper (or many newspapers). This is true for political parties, organizations committed to causes like temperance or the abolition of slavery, religious denominations from the mainstream to the Millerites, and a wide range of immigrant groups. So the belief by black editors that their newspapers could shape the ideas and actions of their readers reflected the broadly accepted view of the power of the newspaper, which could be wielded for good or ill.

In what ways did these newspapers connect through their mission to other nineteenth-century movements, including abolitionism and evangelical moral reform? What I suggest in my book is that black newspapers applied their theories of black chosenness to a range of issues. For example, Freedom’s Journal argued that being a member of God’s chosen nation brought with it the responsibility to act in a certain way. And for that newspaper, acting chosen meant behaving according to certain class-based norms. The paper railed against working-class black New Yorkers for being too loud, too showy, for lacking decorum and humility. So in this example, Freedom’s Journal connected black chosenness to its efforts to instill what its editors called “propriety” in its black readers.

And while I decided to focus on the place of black chosenness in black newspapers, this is only one of many stories we could and need to tell about the early black press. The black newspapers that I study were not single-issue publications. Instead, they covered and commented on a range of topics. These papers were certainly abolitionist, printing speeches from well-known black and white abolitionists and consistently agitating for the end of slavery. But they were not simply abolitionist papers. The same can be said for an issue like temperance, which was taken up frequently by black newspapers in the antebellum era.

To what extent did the editors see inclusion among the American nation as a possibility for African Americans?

The black newspapers I study, with the exception of the Provincial Freeman, absolutely saw inclusion among an American nation as a possibility for African Americans. But crucially, for these newspapers “American nation” did not necessarily equal the United States of America. Instead, the black newspapers that I study consistently imagined God’s chosen people as members of American nations that existed independently of, and at times in opposition to, the United States.

We see this most clearly with The Colored American, a newspaper that at times equated the United States to Babylon, a city that, in the Bible, God eradicates because its people hold the Israelites in slavery. With this connection in mind, The Colored American speculated that black Americans would only find true freedom after the United States had been destroyed. And out of that destruction, the paper concluded, would come a truly free American nation composed of those that the United States had formerly enslaved and oppressed (including Native Americans). Indeed, The Colored American drew an explicit connection between African Americans and Native American tribes like the Seminoles, while also focusing on the history of Native nations that predated the United States. By reminding their readers, and us, that American nations had existed before the United States and will exist after it, black newspapers like The Colored American put some healthy distance between the concepts of nation (or people) and state (or government). There is a long history of U.S. Americans working hard to collapse those two concepts and portray the United States as the natural, inevitable, and only imaginable state of an American nation. But as the contributors to and readers of the black newspapers that I write about in my book recognized, that conflation is designed to eliminate the pursuit of alternative American nation-states free from the oppressive structures and conditions that constitute the United States.

You note, both above and in the book, the difficulty for scholars in gaining access to newspapers because so few of them are digitized. What is the current status of digitization projects for black newspapers specifically, and what work remains to be done?

When I began this project in the early 2000s, I could only access antebellum black newspapers through microfilm and a visit to the American Antiquarian Society, which holds quite a few original issues of the papers I write about in my book. At present, quite a few black newspapers, including but not limited to the five I focus on in my book, have been digitized. These digitization projects have undoubtedly made black newspapers more widely available. The caveat, though, is that the for-profit companies that have digitized and archived these papers charge subscription fees that only the richest universities can afford, and typically do not even offer subscription options for individuals unaffiliated with such institutions. Moreover, the newspaper databases that are freely accessible, such as the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America project, are woefully inadequate in their coverage of black newspapers. So we have a situation where newspapers produced by and for a people who had been bought and sold have been transformed into a commodity accessible only to scholars and students at a select few universities. One of the saddest consequences of this inaccessibility, I think, is the difficulty of bringing black newspapers into the classroom and introducing new generations to the power and beauty of the early black press.

What we need, then, is a freely accessible archive (or archives) of black newspapers (and black print more generally) created and curated by scholars, archivists, and librarians and supported by university libraries. This is a daunting task, especially for folks already overburdened by a range of other professional responsibilities. But projects like the Colored Conventions Project and the Digital Colored American Magazine are models for how this sort of work can proceed, and show that it can be accomplished, slowly, as a collective effort.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.4 (Summer, 2017).

Benjamin Fagan is assistant professor of English at Auburn University, where he teaches courses in early African American literature and culture. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in American Literary History, African American Review, American Periodicals, Legacy, and Comparative American Studies. He is the author of The Black Newspaper and the Chosen Nation (2016) and editor of African American Literature in Transition, 1830-1850, a collection of essays under contract with Cambridge University Press. During the 2017-18 academic year, he is a visiting research fellow at the German Historical Institute in Washington, D.C.