Vulgar Things: James Fenimore Cooper’s “clairvoyant” Pocket Handkerchief

In the fall of 1842, James Fenimore Cooper casually pitched an idea to his British publisher, Richard Bentley. “A thought flashed on my mind the other day, for a short magazine story, and I think I shall write it. It will be called ‘The Autobiography of a Pocket Handkerchief.'” Would Bentley “want such a thing” for his magazine, Bentley’s Miscellany? While Bentley hesitated—he noted the title was “somewhat open to objection”—Cooper did manage to sell the idea to Rufus Griswold, editor of Graham’s Magazine. The piece, Cooper wrote, was an “experiment”: in venue, it was a foray into magazine writing during a period when “books were selling dully”; in form, it was a novel whose narrative conceit gave Cooper the freedom to confront Victorian America’s peculiar habits. As the title suggests, the narrator of the “Autobiography” is an inanimate object, a sentient pocket handkerchief. Raised by the Connecticut River, transported to fields in France, and conveyed to markets in Paris and New York City, the “exquisite” handkerchief passes through the hands of middlemen, shopkeepers, genteel women of taste, and worldly women of fashion. Along the way, it delivers incisive observations about Victorian women’s “attachment” to their “valuables.”

Cooper’s novella was serialized in Graham’s Magazine from January through April of 1843; the next month, it appeared (apparently pirated) as a special supplement to the weekly Brother Jonathan. Bentley published a British edition soon thereafter. Like much contemporary social criticism, Cooper’s story lamented women’s extraordinary expenditures for “fancy articles,” the ribbons, trimmings, and “gew-gaws” so prized as emblems of nineteenth-century fashion sense. Such wasteful spending on luxuries, the tale suggested, was an indication that American women were losing that crucial frugality central to their identity as mothers and housewives. “What young man,” a concerned father asks, “will dare to choose a wife from among young ladies who expend so much money on their pocket handkerchiefs?”

Though the novel offers a broader critique of Victorian American womanhood, it also speaks to a more specific set of issues directly connected to its narrator, the handkerchief. This “menial” object played an important role in women’s self-presentation in the first half of the nineteenth century. The refined woman used this sign of genteel sensibility to artfully highlight a blush or tear. The prop used to dramatize sensitive feeling was—inexplicably to Cooper—also the recipient of considerable feeling itself. Like Desdemona, who “so loves” Othello’s handkerchief that “she reserves it evermore about her/ To kiss and talk to,” American women “caressed . . . fondled . . . [and] praised” their pocket handkerchiefs overmuch. Cooper’s charge in the “Autobiography” is that women’s impulse to invest everyday objects with sentimental meaning dangerously inflames consumer desire and, in the case of the handkerchief, encourages the abuse and misuse of what had once been justly regarded as an “aristocratic” artifact.

Cooper’s conservative social critique, though, runs along unexpected lines. He is less concerned about the handkerchief’s new potential to confuse traditional status distinctions than he is about its capacity to violate taboos related to bodily function. While Cooper rails against the “American notion” that “every thing [be] suitable for everybody,” over the course of the novella it becomes clear that the “worked French pocket-handkerchief” is suitable for no body: the circulation and ostentatious display of the handkerchief exposes an intensely private artifact to public view. In his analysis of the hold this artifact has on women, Cooper questions the disturbingly close historical connections between the achievement of status and the display of “vulgar” things.

Cooper did not invent the conceit of narrator as inanimate object. The object narrative dates to the early eighteenth century in Britain and usually involves currency (Johnstone’s Chrysal; or, The Adventures of a Guinea [1760]) but also includes other articles of daily life: slippers and a bedstead narrate The History and Adventures of a Lady’s Slippers and Shoes (1754) and The History and Adventures of a Bedstead (1784), respectively. The pleasure of these tales comes from the unexpected insights (sometimes salacious) of an inanimate witness to human behavior, able to critically comment on “the Vices, Follies and Manners of the Present Age.” The object usually serves its owner (the slipper protects the foot, the bed provides comfort) who, in return, arbitrarily uses, sells, exchanges, and ultimately devalues it.

Like these protagonists, Cooper’s sentient pocket handkerchief speaks. It has a “mind” and an “espirit.” Pocket handkerchiefs, the narrator explains, “do not receive and communicate ideas, by means of the organs in use among human beings. They possess a clairvoyance that is always available under favorable circumstances.” When held by a human hand, or “pressed against [a] beating heart,” the handkerchief can sense its owner’s thoughts through “magnetic induction.” It has a limited “volition” and is able to “[throw] up a fold of [its] gossamer-like texture” in order to brush away a tear. But even in sympathetic contact with its human host, the handkerchief is essentially a captive. It spends an inordinate amount of time either trapped in bales and shopkeepers’ drawers, idly displayed in shop windows, or toted helplessly around by its insensitive owner.

The first owner of Cooper’s handkerchief, the impoverished French aristocrat Adrienne, purchases it at a Parisian market and spends two months embroidering it. She intends to give the finished work as a gift to her patron, the Dauphine, but when the Dauphine looses her own fortune during the 1830 revolution, Adrienne is forced to sell the “worked” handkerchief to a French merchant for a paltry ten dollars. The merchant, in turn, sells it to an American middleman, Colonel Silky, for twenty dollars; Colonel Silky brings it to his Broadway agent, Mr. Bobbinet. Mr. Bobbinet first offers the handkerchief for sixty dollars but, in a farcical bargaining scene with a wealthy real-estate heiress, Eudosia Halfacre, finally parts with it for one hundred dollars, forty dollars over his asking price. When Eudosia’s father goes bust, she is forced to return the handkerchief to Bobbinet’s shop. Mr. Bobbinet shortly thereafter sells it again, for one hundred and twenty-five dollars, to Julia Monson, another young woman of fashion whose family happens to employ Adrienne, the handkerchief’s first owner, as a French governess. While the handkerchief has come full circle, it sees that its reunion with Adrienne is only temporary. For experience has taught that a consumer object of its kind is always a slave to fortune.

As Cooper follows his object-narrator on its journeys into Victorian womanhood and consumerism, he illuminates a nettlesome fact about his chosen thing: nobody quite knows what to make of it. Various characters ask: What are “these things?” Is the fancy or dress handkerchief a “bijou” or “frippery”—curious feminine ornaments, tied to things foreign? Does it have more social significance, used by women as a “lure” or a “sign” of wealth and understood by male fortune hunters? Is the pocket handkerchief a physical “appendage” or a useful “appliance”—an indispensable part of the body or a disposable tool? A necessary or a “vulgar” thing? In sum, where does such a thing fit in the arsenal of gentility? Where, Cooper asks, does one place a precious object into which the nose is blown? The question was by no means a new one. For centuries, students of manners had been debating the precise social function of the handkerchief.

The handkerchief (from medieval “kerchief,” or head covering) comes into wide use during the mid-sixteenth century, almost a century after general adoption of the table napkin. (The words handkerchief and napkin remain interchangeable into the sixteenth century.) As the historian of manners Norbert Elias demonstrated in his 1939 The Civilizing Process, the handkerchief, like the napkin, is a mark of distinction that serves to regulate behavior as it separates the elite from the common. Erasmus, in his 1530 On Civility in Children (De Civilitae morum puerilium) noted, “To blow your nose on your hat or clothing is rustic, and to do so with the arm or elbow befits a tradesman; nor is it much more polite to use the hand, if you immediately smear the snot on your garment. It is proper to wipe the nostrils with a handkerchief, and to do this while turning away, if more honorable people are present.” The “proper” handkerchief replaces the multi-purpose hand, elbow, hat, or clothing with a specialized textile that manages bodily emanations now experienced as repugnant.

The rise of the handkerchief was not simply a function of shifting social mores. It was also a part of the “civilizing process” through which the haves became readily distinguishable from the have-nots. Bleached white, napkin and handkerchief reveal every stain; only the wealthy can afford to preserve a pristine whiteness through frequent laundering or replacement. But the handkerchief possesses symbolic powers never attributed to the napkin: the latter is never worn or exchanged as a token of love. In his Additions to Stowe’s Chronicle (1580), Howe recorded elegant handkerchiefs, “wrought round about” with “names” and “true love knots.” He noted, “Gentlewomen and others did usually weare them in their hatts as favors of their loves and mistresses.” That the handkerchief became a token meant to be seen and exchanged is due in part to the handkerchief’s further differentiation from the napkin over the course of the sixteenth century: handkerchiefs were made of finely spun linen or silk and were usually embellished with cut-work lace and embroidery.

In large part, though, the handkerchief’s role as a romantic sign was due to the handkerchief’s specialized service: while the napkin manages an external pollutant, food and its greases, the handkerchief ministers the diverse products of the orifices of the face—tears, snot, and sweat. So, when after a hot and sweaty game of tennis played on the lawn in Hampton Court in the spring of 1565, the Duke of Leicester snatched Queen Elizabeth’s “napkin out of her hand and wiped his face,” his actions were perceived as an affront. The implied exchange of bodily fluids bordered on actual violation, and Leicester’s rival, the Duke of Norfolk, took offense. The two men came to blows and the queen, according to an eyewitness, “was offended sore with the Duke ” over the incident. The queen’s (or a lover’s) sweat transforms the handkerchief into something with relic-like status.

The handkerchief’s value, then, at times derives from its menial service: in romantic contexts, the proffered handkerchief (like Desdemona’s offer to wipe Othello’s feverish brow) extends a kindness, as in religious contexts the handkerchief’s absorptive power extends the holy personage. The Geneva Bible, for example, translated in the mid-sixteenth century, mentions a handkerchief intended for charitable acts and endowed with magical properties. One of the miracles associated with the Apostles is Paul’s care of the wounded: “from [Paul’s] body were brought unto the sicke, kerchefs or handkerchefs.” With these handkerchiefs Paul cures the sick: “and the diseases departed from them, and the evil spirits went out of them.” The handkerchief is at once a detachable part of the person and so a potent token; it is also an integral part, a cloth that contains the body at its fluid borders. Its host of associations and uses makes it difficult to separate the handkerchief’s role as physical “appendage” from useful “appliance,” as necessity from “vulgar” aid.

When Cooper writes the “Autobiography,” the mechanization of textile production was making an ever-wider range of handkerchiefs available. “Our shops and warehouses teem with every variety of them,” noted an 1861 commentary in Godey’s Lady’s Book. The design and use of men’s handkerchiefs, in particular, had shifted with seventeenth-century tobacco cultivation and the practice of snuff taking. Aided by innovations in textile printing and improved color—fast dyes, the more practical snuff handkerchiefs were colorful (less likely to show dirt) and often washable, although some were still expensive and luxurious and thus eagerly displayed by their owners. By the 1830s, as the fashion for snuff taking waned, men opted for the more staid white handkerchief tucked in the breast coat pocket. One guide to middle-class conduct, the Ladies and Gentlemen’s American Etiquette (1851-1862), advised men to “always have an extra clean pocket handkerchief in your pocket”; as long as one’s linen was “immaculate” (or “white as snow” according to an 1848 conduct book) it could be “course-poverty does not affect [the gentleman’s] claims to gentility.”

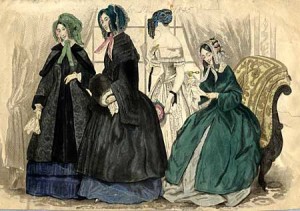

Women’s dress handkerchiefs, in contrast, remained an active accessory, carried in the hand and flaunted. The ubiquity of handkerchief-as-accessory in women’s attire is reflected in the fashion plate that accompanied Cooper’s first installment of the “Autobiography.” As is typical of plates in the 1840s, each woman holds a handkerchief improbably arrayed so that important details—a border of lace or embroidery—is visible. The presence of the fashion plate suggests the challenge Cooper’s piece posed to readers interested in the magazine’s fashion tips (Graham’s like Godey’s advertised their fashion plates aggressively as an important selling point to subscribers). But these plates also suggest what Cooper was up against. The wide dissemination of high-quality illustration offered more than a catalog of the minutiae of fashionable dress. The figures in the group ensemble “Fashions for December, 1845” appearing in the Columbia Magazine, for example, model sentimental style. The plates provide detailed instructions on handkerchief deployment, including the certain way one should flirtatiously pull the handkerchief from the muff while on promenade.

Against this rage for fashionable pocket handkerchiefs, Cooper offers his unlikely intervention, one in which the handkerchief—the object of Cooper’s scorn—makes the case for its own banishment. Unlike most eighteenth-century object narratives, which preface their texts with lengthy explanations from a human editor who has transcribed the book for its inanimate “author,” Cooper’s protagonist boldly begins its life history in the first person. Its “descent,” it explains, is “strictly vegetable.” Cooper plays with an emerging form of the period—the secular autobiography—in which birth is not the final measure of a person’s station. Of “unequaled fineness,” the handkerchief’s “lineage” is nevertheless suspect. Cooper’s narrator admits that its vegetal lineage is common flax, “Linum Usitatissimum” rather than the prized “French cambric” (a linen originally made at Cambray, Flanders). It owes its “being” to a “glorious family of contemporaneous plants” growing along the banks of the Connecticut River. The handkerchief is thus an “American by origin, European by emigration, and restored to its parental soil by the mutations and calculations of industry and trade,” an “aristocratic” artifact of humble birth, eminently qualified to address an American audience.

This humble object has an outsized regard for its own “excellence.” The narrator’s self-evaluation precisely mimics the language of contemporary connoisseurship with its obsessive commentary on the quality of material and craft. French cambric, noted An Encyclopedia of Domestic Economy (1845), was “an intensely fine and beautiful cloth.” In addition to such overblown description, contemporary commentary tended to deny the actual conditions of the object’s manufacture, as satires of this trend make clear. The cookbook author and prolific magazinist Eliza Leslie, for example, chides the protagonist of her 1838 Althea Vernon; or the Pocket Handkerchief for misattributing the fine embroidery on a prized handkerchief to the “fingers of a fairy.” The tales women tell about their treasured handkerchiefs replaced bobbins, shuttles, looms, and the toil of an invisible working class with the ethereal fingers of a fairy or the natural creations of the spider (handkerchief weave structure is most often compared to a “cobweb”). Cooper’s handkerchief directly confronts these fanciful histories. The handkerchief recounts the “painful memory” of its manufacture, recalling how it was “‘pulled’ . . . prematurely” from the earth and subjected to a “parade” of “cruel” procedures—”rotting,” “crackling,” and “hatchel[ing]”—before finally being woven. The handkerchief notes that it is after all “but a speck among a myriad of other things produced by the hand of the creator,” no more deserving of praise than anything else.

More to the point for Cooper, women’s sentimental fancies about handkerchiefs prevent them from using the cloth for its intended function. Drawn by her aesthetic appreciation of the handkerchief’s fineness, Adrienne lovingly and painstakingly embroiders it with needlework that she hopes will match the handkerchief’s delicacy. (Intriguingly, the handkerchief does not record the experience of being pierced by the embroiderer’s needle). With the addition of Adrienne’s “work,” the handkerchief escapes the “more menial offices of the profession;” its role is rather “one of pure parade.” It is, of course, relieved not to be blowing noses. But now, in the service of pure fashion, it is better placed to hear the conversations of Cooper’s right-thinking human characters. And what it hears is that it has come to represent a naïveté and shallow absence of industry. As the wealthy Eudosia’s more sensible friend tells her, intricate needlework is “ingenuity misspent;” a handkerchief “ornamented beyond reason” results in a morally wasteful sort of counter-production. Even as embroidery was viewed as an accepted outlet for women’s creative energies—and as magazine editors supported this claim by consistently printing patterns and instructions—Cooper argued that transforming utilitarian objects into delicate works of feminine art is a “proof of ignorance and a want of refinement” because it “confounds” the intended use of things.

Yet as much as its misuse, the handkerchief’s exposure disturbs Cooper, revealing his ambivalence about an artifact whose complex history suggests that social status is linked not only to the management of rude bodies but also to their display. In opposition to established social practice, Cooper argues that to “wear” a handkerchief to a ball and show it to friends and potential mates is a sign of “vulgarity.” “It is in bad taste” to make “a menial appliance . . . an object of attraction.” Worn to its first ball by the wealthy Eudosia Halfacre, the handkerchief is mobbed by “a bevy of young friends . . . all dying to see me” and is soon “lent to some twenty people that night.” The handkerchief is anxious about the close inspection it receives: “They went from my borders to my centre—from the lace to the hem—and from the hem to the minutest fibre of my exquisite texture.” “It is a queer thing to borrow a handkerchief,” the handkerchief concludes.

One does not expose intimate articles of dress, such as underwear, for example and thus would not display a soiled handkerchief. But by making the fashionable handkerchief an object of attraction, women offer a seductive glimpse of a private, personalized object. The “sweet odors” of the perfumer, in particular, call to mind the body. The handkerchief thus warns that the application of perfume must be preformed with an impossible “tact” to prevent its being “vulgar.” The handkerchief advises women to sprinkle an amount of perfume “just strong enough to fill the air with sensations” but not so strong that it leave “impressions” of the body. (Cooper’s ambiguous phrase is “leave impressions of a woman’s wardrobe.”) The circulation of the dress handkerchief, in Cooper’s view, is equivalent to the circulation of the practical pocket handkerchief—it exposes personal artifacts for public scrutiny.

Where, then, does the handkerchief belong? As Alan Taylor and others have shown, Cooper is a novelist concerned with putting people and things in their place. Yet the handkerchief turns out to be remarkably difficult to place, both in its meaning and its context. If Cooper’s pocket handkerchief was uncomfortable with its public exposure it was still more unnerved by being hidden away in the pocket. Over the course of the entire novel, the pocket handkerchief occupies the pocket only once and then briefly, when Colonel Silky, the American middleman, buys it from the French merchant: “the colonel actually put me in his pocket . . . and for some time I trembled in every delicate fibre, lest, in a moment of forgetfulness, he might use me.” Unfit for use, inappropriate to display, yet not easily contained, the dress handkerchief in Cooper’s view is a “thing out of place.”

By novella’s end, its last owner, Julia Monson, returns the handkerchief to its first owner, Adrienne, who is happy to have the reunion. “No longer thought of for balls and routs” the handkerchief is instead stored away in a closet “on account des souvenirs.” Cooper engineers the handkerchief’s safe removal from the market and fashionable society—as a souvenir, the handkerchief becomes the treasured keepsake (as opposed to the morally suspect fashion object) widely touted in the fiction and domestic treatises of sentimental writers. “Never was an ‘article’ of my character more highly favored,” the handkerchief brags. For Adrienne, this inanimate witness to the course of her life is no longer “an article of dress with me; it is my friend!” As Cooper pointedly shows, these sentimental tales that revealed the empathy between object and owner animated the artifacts of everyday life to a dangerous degree. Adrienne’s loving care, Cooper charges, is not ultimately transformative. Her stewardship cannot shield the handkerchief from its awareness of its status as commodity. For “being French,” the handkerchief notes, “I look forward to further changes;” the handkerchief anticipates “revolutions”—its inevitable return to the market as Adrienne’s feelings or fortunes change again. Sentimental possession, in Cooper’s view, does nothing to bring “men and things . . . within the control of more general and regular laws,” as he envisioned in the 1838 novel of manners Home as Found. The fetishization of treasured objects caused women to expend feeling on a mute “bit of rag,” turning useful things into “senseless luxury.”

Cooper’s attempt to enter the magazine trade proved exasperating: not only did the tale take far longer than the predicted “fortnight” to compose, but its financial returns also proved less than expected. Because of the pirated version in Brother Jonathan, Cooper’s British publisher was unable to secure the copyright, and Cooper probably never received any compensation for the British book edition. In retrospect, piracy may have been a back-handed compliment. Cooper’s “Autobiography” had the potential to reach more people than his poorly received novels of the same period: Graham’s and Brother Jonathan had a combined circulation of seventy thousand compared to the small first print runs of Home as Lost and its sequel, Home as Found (the first American printing of Home as Lost was five thousand). But it is Cooper’s success in animating an inert thing that makes his “experiment” finally less than a success: by breathing life into a cloth “light . . . as air” (Othello), Cooper makes the handkerchief the most sympathetic character in the work—the reader feels for the lively, if vain, handkerchief but rarely for any of its flawed owners. When the handkerchief is “doomed to the closet” (the only nominally secure place for such a thing in Cooper’s view), our sympathies lie with the handkerchief.

Further Reading:

For Cooper’s letters see James F. Beard, ed., The Letters and Journals of James Fenimore Cooper (Cambridge, Mass., 1960-68). JFC to Richard Bentley, Sept. 22, 1842, 4 :315, 4: 315-316, note 4; JFC to Mrs. Cooper, September 29, 1842, 4: 316; JFC to Mrs. Cooper, February 5, 1842, 4: 231; JFC to Carey, Lea, and Blanchard, September 1, 1838, 3: 336. “The Autobiography of a Pocket Handkerchief” originally appeared in Graham’s Magazine, Vol. XXII (January-April 1843): 1-18, 89-102, 158-167, 205-213. On March 22, 1843, it was issued as a separate number of Brother Jonathan magazine under the title “Le Mouchoir: An Autobiographical Romance.” On May 1, 1843, Cooper’s British publisher Richard Bentley wrote to Cooper telling him that he had seen “Le Mouchoir” in Brother Jonathan, was unable to secure the copyright, and had printed it with an alternate title: The French Governess; or, the Embroidered Handkerchief (1843).

On tales narrated by objects, see Christopher Flint, “Speaking Objects: The Circulation of Stories in Eighteenth-Century Prose,” PMLA, vol. 113, no. 2 (March 1998): 212-226. For the role of the object in sentimental fiction see chapter two of Phillip Fisher, Hard Facts: Setting and Form in the American Novel (New York, 1985); Gillian Brown, Domestic Individualism: Imagining Self in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley, Calif., 1990); G. J. Barker-Benfield, The Culture of Sensibility: Sex and Society in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Chicago, 1992).

On the handkerchief see “The Fashions: Pocket Handkerchiefs,” Godey’s Lady’s Book 63 (November 1861): 387; Eliza Leslie, Althea Vernon; or, the Pocket Handkerchief (Philadelphia, 1838): 11; American, Ladies and Gentlemen’s American Etiquette . . . (Boston, 1851-1862): “immaculate handkerchief” reference, 16; American Gentleman, True Politeness: A Hand-book of Etiquette for Gentlemen (New York, 1848): “white as snow” reference, 16.

For secondary sources on the handkerchief see M. Braun-Ronsdorf, The History of the Handkerchief (Leigh-on-Sea (Ex., [1967]); Mary Schoeser, Printed Handkerchiefs (London, 1988); Katherine Morris Lester and Bess Viola Oerke, Accessories of Dress, An Illustrated Encyclopedia (Peoria, Ill., 1940). Lester and Oerke quote Howe’s Additions to Stowe’s Chronicle (1580): 429. See also scholarship of the early modern period that examines the handkerchief in conjunction with Shakespeare’s Othello: chapter two of Natasha Korda, Shakespeare’s Domestic Economies: Gender and Property in Early Modern England (Philadelphia, 2002); Dympna Callaghan, “Looking Well to Linens: Women and Cultural Production in Othello and Shakespeare’s England,” in Jean E. Howard and Scott Cutler Shershow, eds., Marxist Shakespeares (London and New York, 2001). The incident of the queen’s napkin is analyzed by Will Fisher in “Handkerchiefs and Early Modern Ideologies of Gender,” Shakespeare Studies, 28 (2000): 199-208.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.2 (January, 2007).

Hannah Carlson is a doctoral candidate in American studies at Boston University, where she is completing a dissertation on the cultural history of the pocket and pocketed possessions in nineteenth-century America.