Was Slavery Really Not A Major Issue in American Politics Before the Missouri Crisis?

Debunking the Myth Without the Aid of a Method or an Online Database

At my dissertation prospectus defense, one of the committee members posed a question that vexed me even more than the others faced that day. “What,” he inquired, “is the method to your madness here?” He noted that I had listed a whole series of sources but proposed no research method other than to “just read these newspapers and sermons and congressional debates.” I stammered out some half-baked reply, he urged me to find a method, and we moved on. At some point after this defense, I surely became a more efficient researcher. But I’m not sure I’ve found a better method than “just reading” the sources with an eye to the research question at hand.

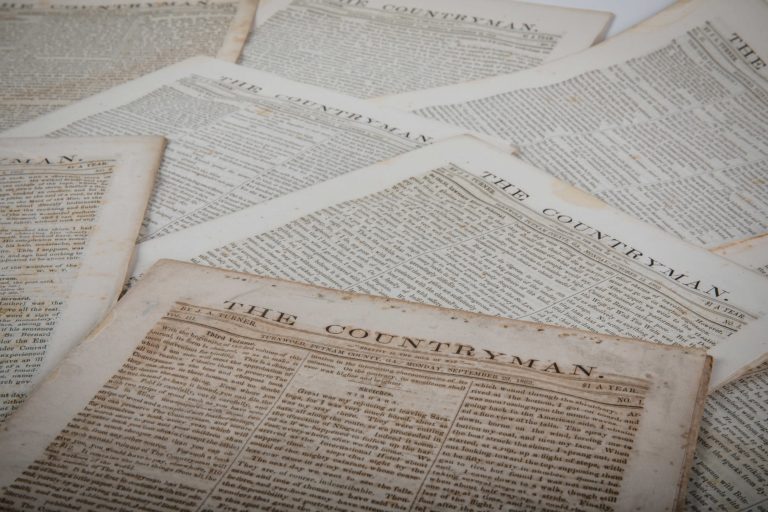

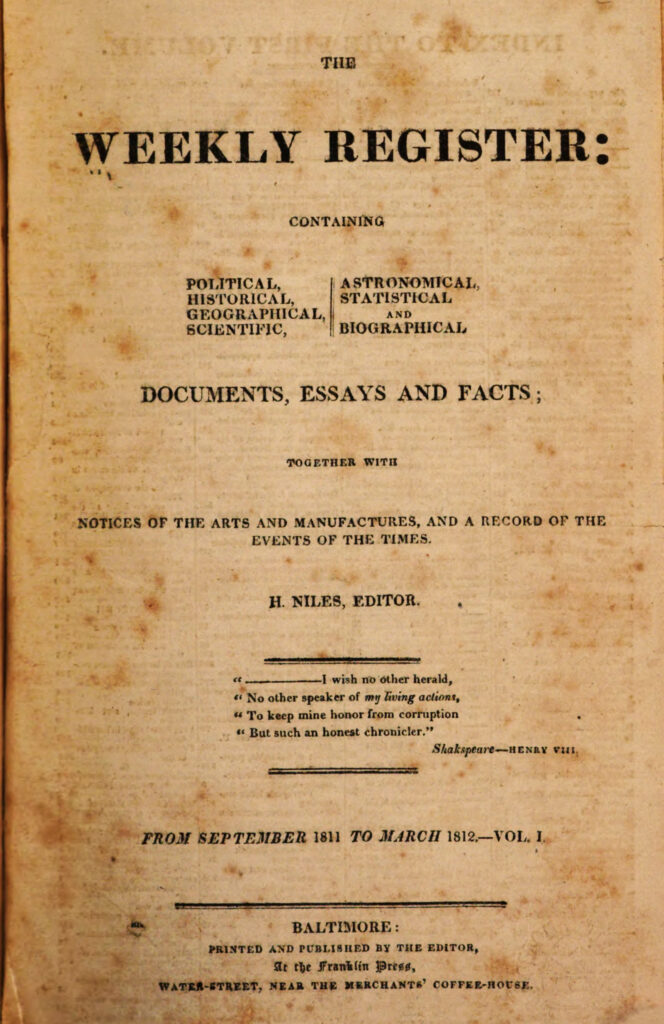

If I had actually obeyed the injunction to find some more selective or systematic approach to the sources, I may not have written this particular dissertation and book, Slavery and Politics in the Early American Republic, in the first place. This because I quite literally began this research by just sitting down and reading the newspaper: Niles’ Weekly Register, one of the very few truly national publications of the early nineteenth century.

My question was whether slavery really disappeared from national politics between the abolition of the slave trade in 1808 and the Missouri Crisis beginning in 1819. The common wisdom was that the partisan and international fury surrounding Jefferson’s Embargo on foreign trade and the War of 1812 took slavery off the table in national politics. I thought this national newspaper in particular would be a good place to inquire as to the truth of that historiographical consensus.

Hezekiah Niles published his Weekly Register in volumes and bound them with an index, but fortunately I did not discover that right away. The lack of index entries for such terms as “slavery” or “negroes” would have confirmed the traditional take on this era, as would a glance at the headlines and topic headings on each page. But here’s where just reading the thing paid off: I found slavery everywhere in Niles’s coverage of those headline events and issues, even though none of them had anything overtly to do with slavery. Here was a prowar (Democratic-)Republican comparing the Royal Navy’s impressment of American sailors to Algerian or West Indian or even southern slavery. There was a Federalist campaign to abolish the Constitution’s three-fifths clause – which they commonly branded “slave representation” – in response to a wicked war the “Virginia dynasty” ruling in Washington had brought on the country. There in turn was Niles and other Republican editors casting about for good replies to this Federalist attack on the power of slaveholders. Yet none of these tactics in the larger partisan struggle showed up in the index, which was quite naturally devoted to the main subjects at hand, like the war.

I found the same thing whether I sat down to “just read” fiery sermons from New England Congregationalist divines, antiwar or prowar pamphlets, or the Annals of Congress. Indeed, ignoring the inadequate index and page headings to the congressional debates paid the same dividends as doing the same for Niles’ Weekly Register. In the course of their diatribes against the war, for instance, various congressmen warned the southern warmongers that slave insurrection would be a natural and just consequence of their leaving their plantations to invade Canada. One of the great moments came as I waded through an 1813 debate over expanding the army – yes, there was a bitter partisan dispute over such a radical notion in time of war – when I encountered Josiah Quincy of Massachusetts charging that the expanded army would march north to drag the administration’s political enemies into slavery, yoking them in with the black slaves over which the Virginia despots ruled. And on and on it went in much this same fashion, as I encountered slavery everywhere in debates that should have borne no direct relationship with slavery whatsoever. It became clear that the subject of slavery was never truly absent from American public life.

It also became quite clear why so many previous scholars had argued that slavery had subsided as an issue in these years. The 1810s were manifestly not the 1850s, when slavery was the headline issue around which everything else revolved. The whole exercise showed that unearthing new documents is not always the Holy Grail of historical scholarship. In this case, as with so many others, examining old familiar sources with a new question in mind generated surprising conclusions.

While a blog post may be a strange place to air this particular moral to the story, the whole experience makes me tremble just a little for my profession as I see the proliferation of online databases make such sources as early American newspapers more widely available. This development has undeniable payoffs, which even my (strong) inner Luddite is not inclined to dispute. But researchers doing only word searches will miss not only context, but also what might lurk just beneath the headlines.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Matthew Mason is an assistant professor of history at Brigham Young University. He is the author of Slavery and Politics in the Early American Republic (UNC Press, 2008).