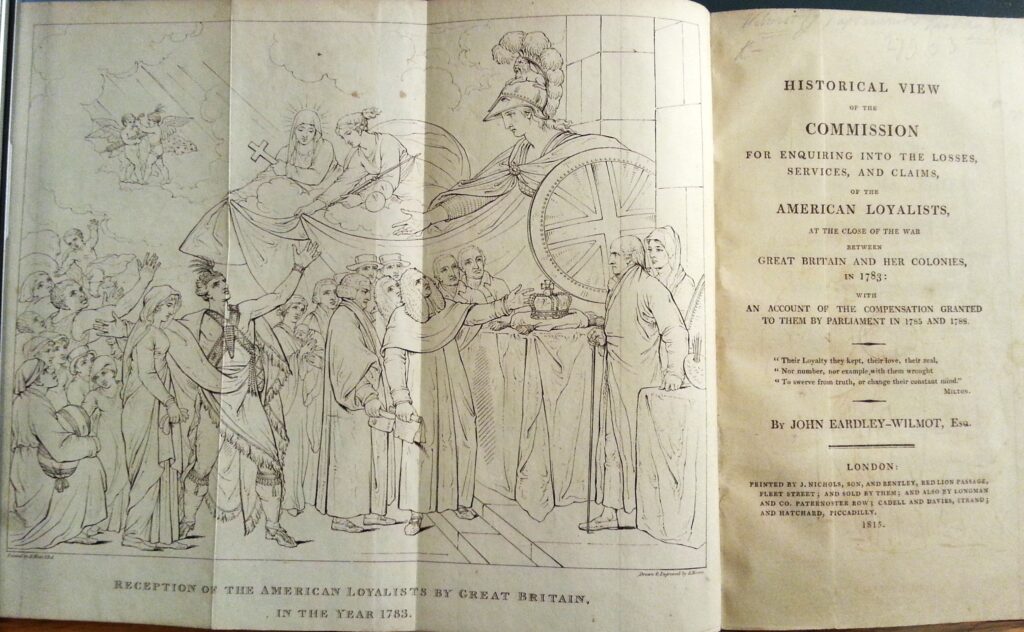

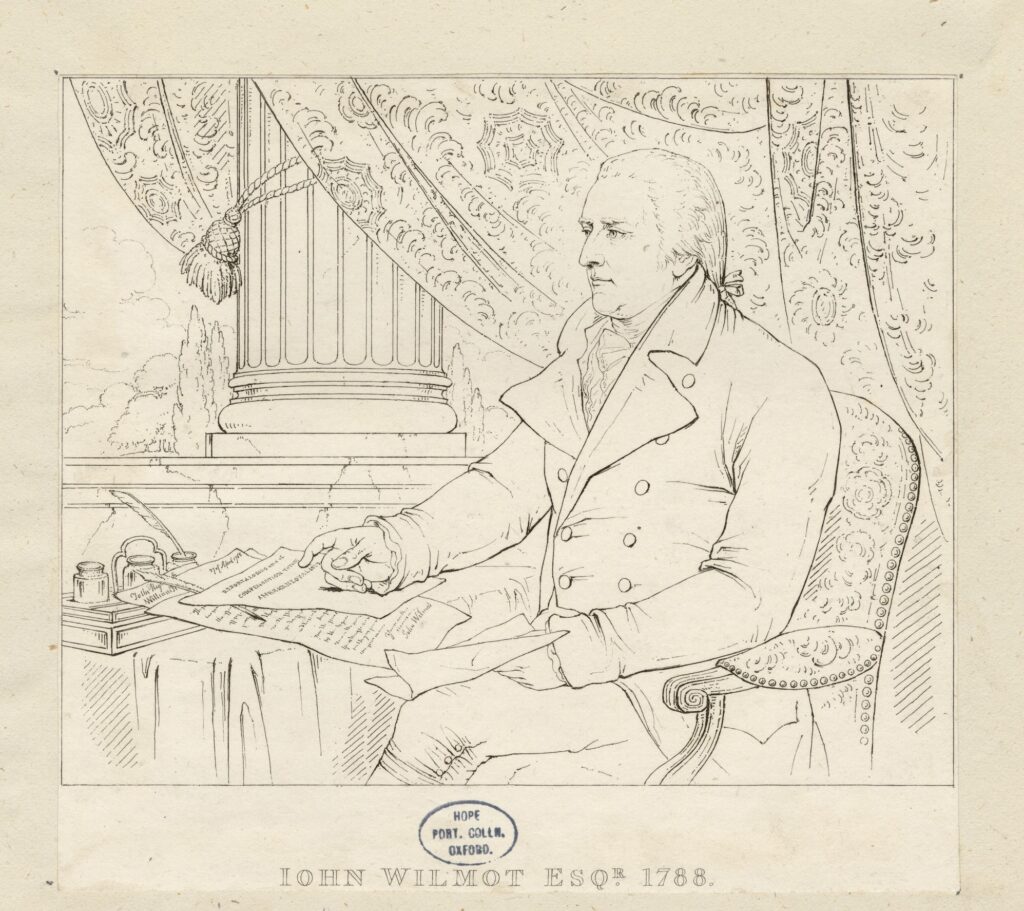

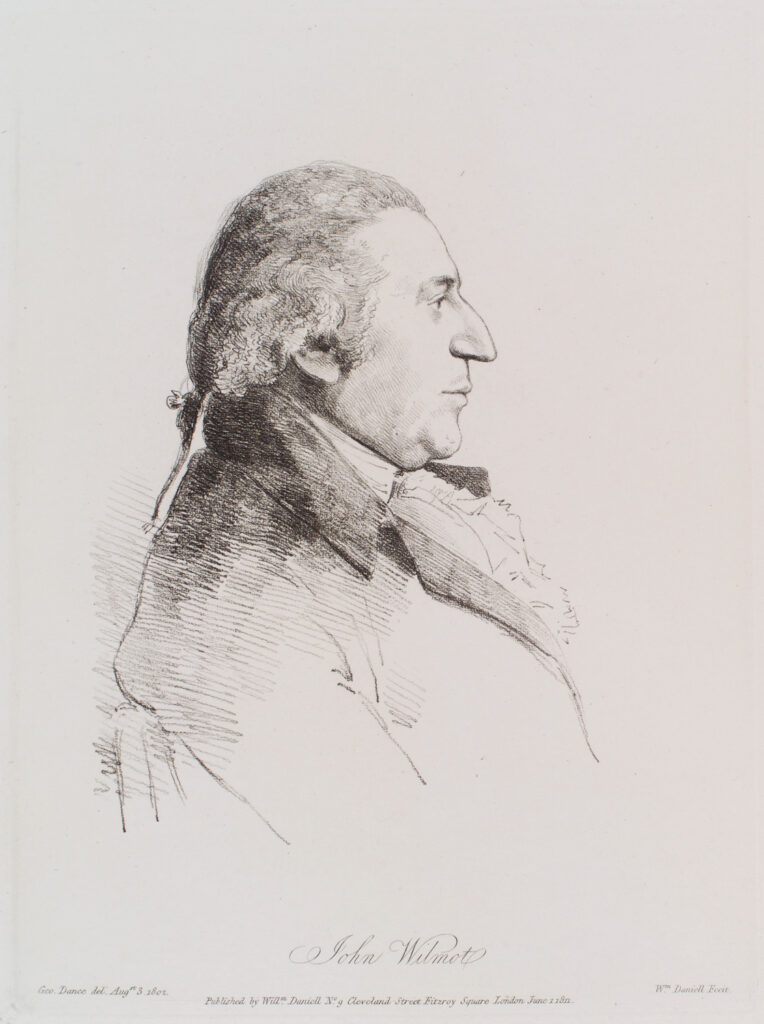

The print of Wilmot in profile by Heckel or Dance, the print of Wilmot at the Ashmolean, West’s oil self-portrait in characterful pose, and the whole scene of the Reception frontispiece print would together have provided sufficient material to re-create the Portrait.

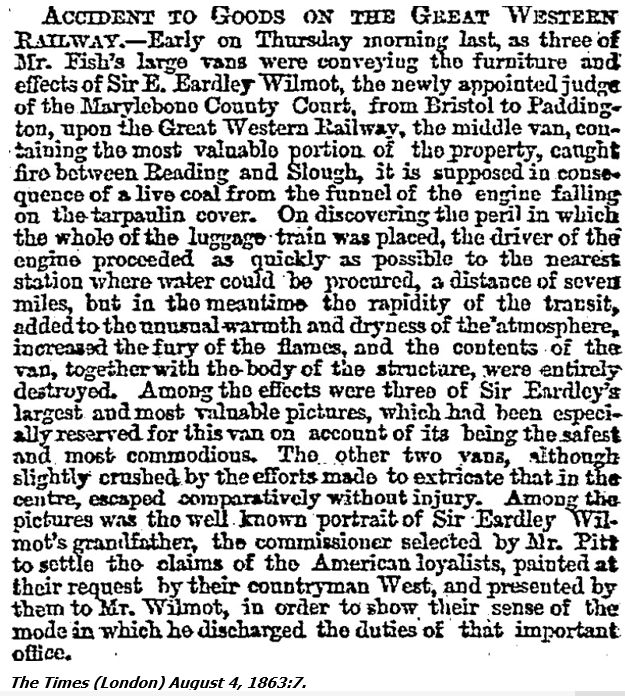

So, did the fire really happen? The Railway Passengers Assurance Company were the main insurers for railway accidents at that time. I searched the board minutes for 1863 through 1864, held at the London Metropolitan Archives, but their insurance only covered bodily harm of people, not for goods. I went to the National Archives in Kew, London, (where the compendious volumes of Wilmot’s Commission are also held) to look for the board minutes of the Great Western Railway Company. For August 5, 1863 I found: “Mr Grierson reported that a Van of furniture belonging to Sir Eardley Wilmot had been destroyed by fire . . . for which a claim has been sent in of £500 for the furniture and £98 for the Van. Instructions were given to . . . offer reasonable compensation for the Van & furniture. But to decline all liability for sundry pictures destroyed which were not insured.”

My opening question is unanswered. I’ve linked the painting with its engraving, searched out parallel images, found sought out evidence for inheritance, and I’ve confirmed the fire. But I haven’t found an explanation. Perhaps the attention of Commonplace readers and new approaches can lead to a resolution.

Further Reading

Note: “John Wilmot” was how Wilmot styled himself up to 1812, when by royal deed he joined his father’s name Eardley to his own surname, becoming John Eardley-Wilmot. His son gained a baronetcy, his grandson Sir Eardley-Wilmot 2nd Bt lost the pictures in the fire in 1863 and the heirs of Sir Eardley-Wilmot 4th Bt sold the Portrait in 1970.

I am grateful to Yale Center for British Art for guidance about the Portrait. Writing mentioned in the text includes: John Eardley-Wilmot, Historical View of the Commission for Enquiring into the Losses, Services and Claims of the American Loyalists at the Close of the War between Great Britain and her Colonies, in 1783: with an Account of the Compensation Granted to them by Parliament in 1785 and 1788 (London: self-published, 1815); Mary Beth Norton, “Eardley-Wilmot, Britannia and the Loyalists: a Painting by Benjamin West,” Perspectives in American History 6 (1972): 119–31; Margery Weiner, John Eardley-Wilmot, A Man of his Time, (London: Edmonton Hundred Historical Society, 1970); Lucy Peltz, Facing the Text: Extra-illustration, Print Culture, and Society in Britain, 1769–1840 (San Marino Calif.: Huntington Library Press, 2017).

This article originally appeared in May 2024.

Mark McCarthy is a graduate of the Institute of Historical Research, University of London, and an historian of Camden Town. Wilmot Place is the (unexplained) name of a local street. Lord Camden upheld democratic rights for the American colonists pre-Independence. A longer article on how Benjamin West’s painting of John Wilmot came about, in the context of British and American history, is awaiting a publisher.