Washington in China: A Media History of Reverse Painting on Glass

Object Lessons is sponsored by the Chipstone Foundation.

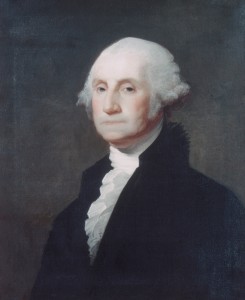

On April 3, 1802, the merchant vessel Connecticut arrived in Philadelphia after a year in Canton, then the sole port of foreign trade in China. In addition to the teas, silks, Nanking cottons, and porcelain wares destined for American markets were trunks of personal merchandise consigned to the ship’s captain, John E. Sword, a veteran merchant seaman returning from his second Canton run. Sword’s 1801 purchase abroad included an unlikely group of objects of Chinese production: portraits of George Washington painted on glass (fig. 1). In a surviving example now at the Peabody Essex Museum, Washington’s serious visage glows beneath the crystal-clear pane and his white lace and silk collar, carefully rendered in precise, flowing brushstrokes, stands out sensuously against his flat, inky coat.

At the height of the Canton Trade, an American ship captain commissioned Chinese artists to copy portraits of George Washington onto glass. His fragile imports sparked an 1802 Philadelphia court case concerning copyright infringement. How might we unpack the layers of technical virtuosity and cultural exchange that made such objects possible?

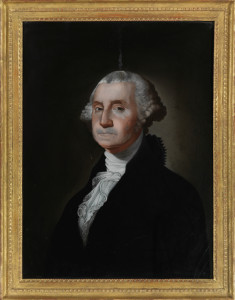

This set of paintings was no doubt imported to meet a growing American demand for Washingtonia. A celebrated national hero in 1802 (three years following his death), Washington had become the subject of a proliferation of images, from grand neoclassical marbles to schoolgirl samplers. In this instance, Philadelphians would have found Washington’s glass portrait uncannily familiar, since it replicates a well-known oil painting by Gilbert Stuart, which had been in circulation for several years (fig. 2). Though a precise copy of its model in composition, the technique of reverse painting on glass gives Washington’s portrait a look of reflective, crystalline liquidity. Why might Sword have chosen such an uncommon technique to reproduce Stuart’s painting, and how might American audiences have received this unfamiliar medium?

Unlike other examples of Washingtonia from the early nineteenth century, the glass portraits emerge from a trans-oceanic world of commerce. Onboard the Connecticut, they traversed the Indian Ocean and rounded the Cape of Good Hope before crossing the Atlantic to arrive in Philadelphia. Such circumnavigations are central to the history of many export arts, but it is surprising to find that glass, an especially fragile material, would have been chosen to produce portable artifacts destined to travel. Moreover, considering their impressive size (over two feet long) and high clarity, the glass sheets on which the Washington portraits were painted could only have been produced in Europe and brought to Canton via North America, adding to their miles logged. All this suggests that reverse painting on glass, though a part of many folk art traditions worldwide, was a medium of particularly high stakes in the context of the China trade and its far-reaching global networks. Indeed, the practice of glass painting was perfected to an unprecedented degree in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Canton.

Reverse painting on glass can only be understood in relation to the international commerce that propelled its growth and development. The Washington portrait, in particular, offers us an opportunity to combine this commercial history with an exploration of the material conditions of painting on glass. How does the fragility and reflectivity of glass painting, for instance, relate to its status as a reproductive medium, favored for replicas and copies? Did the medium’s highly involved procedures offer its makers or consumers insight into practices of visual reproduction across cultures and distances?

Painting for Export

Reverse painting on glass is not a native tradition in China. It has origins in the West and grew in tandem with east-west maritime trade. The earliest references to painting on glass in China date back to the mid-seventeenth century, with the Jesuit introduction of Western technologies including glass and mirror production to the Kangxi court. The emperor’s fascination with Western technologies led to court-sanctioned experiments with foreign media and subject matter in the arts. Both missionaries skilled in painting and a select group of European artists who took up residence in the imperial court could have trained local artists in oil painting on glass. By the 1750s, the production of glass paintings had shifted to Canton, where it became a specialty of export painting workshops. For their foreign clients, these shops offered glass paintings in a range of Western and hybrid subject matter, though copies of Western paintings and prints were especially popular. The medium, as we shall see, was particularly well-suited for the work of replication.

Painting Washington would hardly have been a novelty for Cantonese artists in 1802. Export art workshops had long been adept at catering to new waves of foreign consumers, and when Americans first entered the China trade in 1784, patriotic themes related to the recent Revolution quickly entered their repertoire. The novelty of Sword’s Washington portraits was thus not their subject matter, but their mode of circulation. In Canton, art market purchases were often made on a small scale, intended solely for private consumption. Only high ranking officers and merchants were allowed on land, and their movements were highly circumscribed—limited to the city’s foreign “factories,” a group of Western-style buildings designed specifically for conducting international trade, and the surrounding shopping streets. Trade in high-volume commodities was handled by supercargos in negotiation with the Chinese representatives of the Co-hong, a government-sanctioned guild of merchants. Glass paintings and other artistic goods, including fans, tortoise-shell and lacquer wares, special-order porcelain pieces, furniture, and works on paper, were not formally traded in such transactions, but rather purchased by officers and merchants directly from Cantonese artisans. Once they left China, such artifacts served as personal mementos of the voyage and circulated through gift exchange and inheritance. Though many export artifacts were replicas of existing artworks, their limited circulation kept them from public view.

Copies and Counterfeits

Sword’s decision to sell his Chinese artworks transformed a typically private mode of consumption into a public commercial venture. His entrepreneurship proved problematic when Gilbert Stuart, then also residing in Philadelphia, learned of the sales and moved to sue Sword for copyright infringement. Stuart argued in the Eastern District Court of Pennsylvania that he had earlier sold Sword a portrait of Washington on the condition that “no copies thereof should be taken.” He later discovered that Sword “did shortly afterwards take the same with him to China and there procured above one hundred copies … by Chinese artists and hath brought the same copies to the United States, and proposes to vend them.”

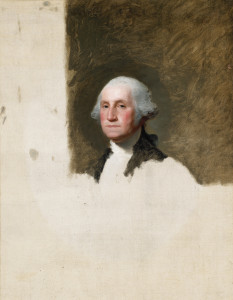

While the case proceedings traffic in the language of forgery, Sword did not necessarily intend for the portraits to sell as counterfeits. Given that some portion of the 100 copies Sword commissioned were paintings on glass, it is almost certain that their purchasers would have been aware of their Chinese authorship and thus satisfied with their seemingly contradictory status as both national symbol and foreign curio. Complicating the case further is the fact that the “original” painting referenced in the lawsuit is but a copy—one of over sixty identical portraits Stuart sold for $100 a piece. Each is a replica of an unfinished work now known as the Athenaeum Portrait, produced during the president’s 1796 sitting for the painter (fig. 3), which Stuart kept in order to capitalize on the public demand for Washington’s portrait.

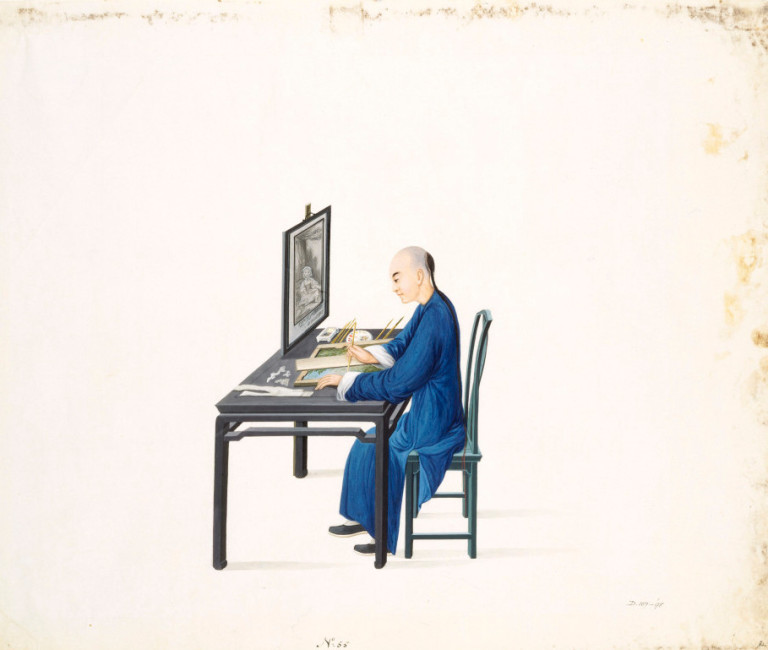

The legal case against Sword and his Chinese Washingtons brings to light the instability of terms like “original” and “copy” in export art contexts. Copying existing artworks in the same or another medium was a standard service offered by artists in Canton. Given its transparency, glass was an ideal support for copying existing images. In an account of his 1836 visit to one Chinese painter’s workshop, nineteenth-century British traveler C. Toogood Downing observed artists working with “a great many prints from Europe.” He goes on to write that “by their side are placed the copies which the Chinese have taken of them in oil and water colours. Many are brought thither by the officers of the vessels, who exchange them for native drawings, or frequently for the copy which is taken of them.” For many Western observers, manual reproduction of this sort constituted a form of subservient labor. They dismissed Cantonese artists as mere copyists, capable of “wonderful fidelity” but little else. The British traveler John Barrow, for instance, insisted in 1804 that the Chinese “exercise no judgment of their own. Every defect and blemish, original or accidental, they are sure to copy, being mere servile imitators.”

Complicating the Copy

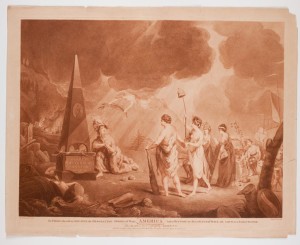

How does reverse painting on glass, a medium decidedly associated with the China trade, fit into such negotiations of artistic labor? While glass paintings made after prints may be highly faithful, they have a complex relationship to their models. Take for instance the allegorical painting entitled America (fig. 4), which is based on an engraving by Joseph Strutt (fig. 5). The detailed glass picture shows a lamenting America at the edge of a war-ravaged city consoled by the figures of Peace, Liberty, Virtue, Industry, Concord, and Plenty. The painter has copied onto glass the print’s marginal inscription word for word (“To those, who wish to sheathe the desolating sword of war …”) and painted the gold border from the mat in which the print was framed. While Barrow may have dismissed such details as thoughtless replication, we might also interpret them as the artist’s attempt to reproduce an artwork as not just flat image but as three-dimensional object, reanimated in full color.

Such compositional decisions were part of a sophisticated process of translation—from print to painting, line to color, paper to glass—that entailed a complex series of reversals and inversions. The artist first traced the original through the sheet of glass placed directly over it. He then turned over the transparent sheet to fill in a now-reversed composition freehand from sight (the original tracing would later be erased from the unpainted glass surface). In a Chinese watercolor documenting the second stage of the process (fig. 6), the original framed print hangs vertically before the artist, who is shown working on a horizontal glass surface. The composition on which he works is flipped: the foliage on the right of the original print is on the left in the unfinished copy. Any textual inscriptions, like those in America, would have added an additional layer of complexity since letters had to be painted as mirror images of the original. In other words, for the Washington portrait on glass to maintain the same orientation as Stuart’s Athenaeum composition, with the figure facing left, the artist had to paint Washington facing to the right.

In this way, the practice of glass painting shares in the technical logic to printmaking, another medium for reproduction. To make an engraving after a painting, a common practice at the time, a printmaker had to reverse the composition on his metal plate in freehand so that the final print could register on paper in the same orientation as the model painting. Yet despite their shared technical strategies, printmaking and reverse-glass painting occupy opposite ends of the spectrum of visual reproduction. While printmaking is a mechanical process designed to create multiples from an original (often paintings), reverse glass painting manually turns multiples (often prints) back into singular originals. The glass painting America, for instance, is in many ways materially closer to the now-lost painting on which Strutt’s print was based, a 1778 work by the British anti-monarchical artist Robert Edge Pine. In its relationship to its model, a glass painted replica constitutes a complicated return to originality.

Beyond the Copy: Reversals and Inversions

Glass paintings may best be conceptualized as copies-in-reverse. Their production involved not only physical but also temporal inversions of oil on canvas or panel. Since the image on glass is rendered on what is technically the back of the support, artists had to start by painting the finest details closest to the surface before gradually moving toward the background—the equivalent of building a pyramid from the capstone down. For Washington’s portrait, this means that the furled edge of the sitter’s collar and the highlight along the ridge of his nose would have been the first marks set down on the glass, while the brown background surrounding the body would likely have been the last. Such protocols of working on a transparent support counteract the very material advantages of oil paint as a medium, namely its potential for building subtle contours by layering lighter colors atop darker ones and its possibilities for revision by overpainting. On glass, even the subtlest highlight had to be planned out in advance, thus precluding compositional improvisation or correction. As a regimented system of image construction, reverse glass painting seems ideally suited for replicating existing images. Paradoxically, however, the procedures of this replication only distance the original from the copy.

Manual copying, generally speaking, requires an artist to constantly compare her imitation to a referent. Imagine Gilbert Stuart painting a Washington portrait from his Athenaeum model. To create a faithful copy, Stuart constantly looked between the model and the replica in order to calibrate each successive mark. Painters on glass, meanwhile, were not privy to the direct feedback loop of copying since they produced doubly inverted images (reversing left-right and surface-depth). For them, the mediation between original and copy (between Washington on canvas and Washington on glass) entailed the invention of visual tricks, which reorient the model as would a mirror, or peel away its layers as might an X-ray (though this analogy is clearly anachronistic). It is often said that mechanization is responsible for the erasure of technical knowledge about how raw materials are transformed into end products. Ironically in the case of Chinese glass paintings, the visual similitude achieved through complex craft labor gets misread by Barrow and other observers as a form of “mechanized” reproduction.

The glass painters of Canton were sophisticated theorists of reproduction. Perhaps in an effort to preserve signs of their technical knowledge and optical skills, they often painted on mirrors, surfaces designed for inversion and doubling. European-made mirrors were brought to Canton, and there artists scraped off the silvering in areas where paint would take its place. In designing such mirror compositions, glass painters were intentional and strategic in their deployment of reflectivity. In a 1780 portrait of Mrs. and Miss Revell, the wife and daughter of a British East India Company supercargo (fig. 7), the artist has organically incorporated a large section of mirror as the sky of the landscape surrounding the two figures, who are dressed in Chinese costume and seated in a Chinese-style porch. The painted trees and architectural features surround the mirrored space like a sinuous, decorative border. Like Washington’s portrait, the likeness of the two sitters would have been taken not from the flesh (women were forbidden to enter Canton), but from existing pictures, copied in reverse. Once hanging in the home of the sitters, the picture would still have functioned as a mirror, reversing the features of any viewer who stood before it and rendering his or her reflection a part of the image. Such instances of reflection mimic the artist’s work of painting the embedded portrait, a process that involved reversal at multiple levels.

For Philadelphians circa 1800, the appeal of a Chinese Washington on glass must have extended beyond its status as a replica of an already popular artwork. Surely, more sound counterfeits could be had. Rather, the object speaks to the very nature of replication as an artistic enterprise that negotiates original and copy, singular and multiple. Perhaps the very flowering of glass painting during the Canton trade had to do with the unique ability of this medium to encode the reversals involved in its own making—to make visible the creative labors erased by the assumptions of reproduction governing export art.

Further Reading

For period accounts of travel to China, see Toogood Downing, The Fan-Qui in China, 1836-7, vol. 1 (London, 1838) and John Barrow, Travels in China, Containing Descriptions, Observations, and Comparisons, Made and Collected in the Course of a Short Residence at the Imperial Palace of Yuen-Min-Yuen, and on a Subsequent Journey through the Country from Pekin to Canton (London, 1804).

On the decorative arts of the China trade, see Carl L. Crossman, The Decorative Arts of the China Trade: Paintings, Furnishings and Exotic Curiosities (Woodbridge, U.K., 1991); David S. Howard, A Tale of Three Cities: Canton, Shangai & Hong Kong. Three Centuries of Sino-British Trade in the Decorative Arts (London, 1997); Patrick Conner, The China Trade, 1600-1860 (Brighton, U.K., 1986); and Craig Clunas, ed. Chinese Export Art and Design (London, 1987).

On China trade exports and the American market, see Jean Gordon Lee, Philadelphians and the China Trade: 1784-1844 (Philadelphia, 1984) and David S. Howard, New York and the China Trade (New York, 1974).

On reverse glass painting as a medium, see Reverse Paintings on Glass: The Ryser Collection (Corning, N.Y., 1991) and R. Soame Jenyns, “Glass and Paintings on Glass” in Chinese Art III, revised edition (New York, 1982): 95-126.

On Gilbert Stuart’s Washington portraits see Egon Verheyen, “‘The most exact representation of the Original,’: Remarks on the Portraits of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart and Rembrandt Peale,” History of Art 20 (1989): 127-140 and Carrie Rebora Barratt and Ellen G. Miles, Gilbert Stuart (New York, 2004).

On Chinese-made Washington portraits, see E. P. Richardson, “China Trade Portraits of Washington After Stuart,” PMHB 94 (Jan 1970): 95-100, and Homer Eaton Keyes, “The Editor’s Attic—A Chinese Washington,” Antiques 15: 2 (1958): 109-111.

This article originally appeared in issue 15.4 (Summer, 2015).

Maggie Cao is a Mellon Research Fellow at the Society of Fellows in the Humanities at Columbia University. She is writing a book on the end of landscape in nineteenth-century American painting, which is forthcoming from University of California Press.