‘We Are All Savages’: Scalping and Survival in The Revenant

When The Revenant was released in 2015, it received widespread praise for its stunning cinematography and its visceral imagining of the American West—and was one of the big winners of the award season, collecting several Oscars including Best Director for Alejandro Iñárritu and Best Actor for Leonardo DiCaprio. Based on the real-life travails of Hugh Glass, a fur trader who legendarily survived being mauled by a bear and then abandoned by members of his party in 1823, the film invokes Glass as a Western archetype: the frontiersman going to fierce, heroic lengths to survive. Glass’s relentless pursuit of the men who deserted him (and DiCaprio’s relentless pursuit of that Oscar) received most of the critical attention given to the film. Yet for those interested in the history and myth of the American West, the film’s villain, John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy), deserves a closer look. His invented backstory marks him as another survivor of the brutal Western environment—indeed, as another “revenant” raised from the dead. Fitzgerald is a scalping survivor.

Viewers discover this early in the film, when he unwraps a leather bandanna from his head and reveals a scarred stretch of skin where his hairline should be. While modern filmgoers might find the idea of surviving a scalping unfamiliar, even implausible, The Revenant is not being fanciful here. Scalping survivors were not uncommon sights in early nineteenth-century America. These mutilated individuals appeared in regions including Kentucky, Tennessee, and lands farther west, products of near-continual conflict created by American invasions of Native lands. As one Tennessean recalled in the 1850s, his childhood settlement had “fifteen to twenty persons who for years survived” scalping, which he called a “rude and bloody treatment.” Fifteen survivors in a community of a few hundred people meant that nearly everyone would have known, seen, or been related to someone who had been scalped.

Americans who didn’t venture out to the frontier, however, might encounter equal or greater numbers of scalping survivors in print. While some newspapers described scalped individuals in detail, announcing their names, locations, and recovery processes, most mentioned these individuals only in passing: “a young man of South Carolina” who had gone to Tennessee, or a little girl collecting firewood. Such vague or anonymous stories are difficult to verify, and make historical numbers loose estimates, at best. Yet what these numerous recountings make clear is that survivors, and the fear and interest their tales provoked, were both powerfully present in nineteenth-century America.

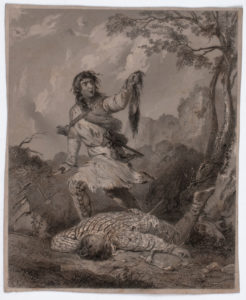

Literature amplified the impact of scalping, with survivors appearing in everything from memoirs of the post-Revolutionary generation to accounts of recent expeditions up the Missouri and the emerging genre of frontier tall tales: history, fiction, and the embellished border in between. These regional literatures, as Jon Coleman has put it, emphasized “the violence done to and committed by frontiersmen” in order “to knit new territories into the nation.” That violence sometimes took the form of encounters with wild animals (as with Hugh Glass) but stories even more frequently promised exciting narratives of “thrilling incidents of Indian warfare.”

Real or imaginary, survivors could be deployed as stock characters in the national drama of conquest. Depending on the angle, they might seem tragic or valiant, but either approach could justify settler colonialism. Such narratives extended U.S. claims to the rest of the continent while also flattering an emergent nationalism that claimed a distinct, superior identity to both Europeans and Native peoples. Survivors might have damaged bodies, but stories could redefine that damage as evidence of American fortitude, and position a survivor as “a convincing witness of the barbarity of the savage red man.” In the era of James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, accounts of white Americans fighting wild animals and “savages” made for popular reading. Such texts reveled in a pleasurable melancholy, inviting readers to mourn what had been sacrificed in the conquest of the West while simultaneously celebrating the inevitable triumph of American expansion. As a result, tales of frontier life were populated with scalped characters, who could supply readers with a reliable shock as they pulled off their hats, handkerchiefs, or wigs to reveal their scarred heads.

Permanently and unmistakably scarred by an act of violence associated with Native Americans (whether or not they were the actual perpetrators) the bodies of scalping survivors were visual evidence for the narratives the nation wanted to tell itself. But those stories were always already contested: Were survivors evidence of American superiority and resilience? Or vulnerability? The uneasy fascination with the scalping survivor as stock character in early American stories demonstrated a struggle to find meaning behind their continued existence. One author worried that Native attackers perhaps did not always intend to kill, as they “always scalped when they could, repeatedly inflicting this mark of dishonor with … little danger to life.” Another explained in a children’s history book that “Indians … would sometimes scalp women and children, whom, for some reason, they did not choose to kill.” Such comments reflected concerns about the intent behind the act: Was scalping intended to annihilate or humiliate?

As pseudo-historical or stock characters, scalping survivors could be tragi-comic, occasionally mentally unstable, intractably anti-Indian. Always, they functioned as an embodied locus of memories for their local communities, signs of a violent past. The story of David Hood is a prime example. In 1782, near Fort Nashborough (what would later become Nashville) Hood was shot, scalped, and left for dead by a party of “Indians” otherwise unidentified in the sources. The next morning, he was found by residents of the fort. When asked if he “wasn’t dead” yet, Hood supposedly replied, not if he could have “half a chance.” Hood recovered and locals described him as “a man raised from the dead.” Soon nicknamed the Opossum, for his success in playing dead, Hood reportedly joked about the advantage his scalping had given him, since, in his words, “the savages” could no longer “get another trophy,” he said, or “jerk [him] by the hair of the head.”

These accounts came from Tennessee histories published decades later in the mid-nineteenth century, however, meaning that Hood’s words and actions come to us indirectly, at best. More likely, they reflect the desire of regional authors to tell a satisfying tale of a settler who “hoodwinked” his careless assailants. Hood insisted on his own role in saving himself, claiming to have deliberately feigned death in order to deceive his attackers, and thereby asserted an identity as a clever “opossum” and not a victim. Yet textual hints show Hood as not fully in control of his own narrative. Other community members portrayed Hood as wacky, garrulous, compulsively making reference to his traumatic experience. Becoming the Possum may have been Hood’s only option for explaining this life-changing event to himself, but his version of the story was repeatedly destabilized by other Tennesseans.

Survivors were regarded as something less than heroes, more than victims: perhaps because they were an uncomfortable reminder that settler colonialism remained contested, that indigenous societies refused to vanish, to cede lands without a fight. Perhaps for that reason accounts often contained storytelling sessions, embedded narratives which permitted (or forced) scalping survivors, whether real or fictional, to narrate their own marked bodies. “To gratify the curiosity of inquirers” within the text meant explaining their scars to its readers, as well.

The Revenant employs a similar method. Early in the film, Fitzgerald’s brutal and precise recounting of his scalping by the Arikara puts pain at the center of the story and in doing so complicates audience perceptions of him. “The Ree done that to you?” asks Jim Bridger while they wait for Glass to die of his wounds. “Yeah they done it,” Fitzgerald replies, explaining that his attackers “took their sweet time with it too. To start I didn’t feel nothin’, just the sound of knives scrapin’ against my skull, them all laughin’ and hollerin’ and whoopin’ and what not … then the blood came, cold, start streakin’ down my face, breathin’ it in, chokin’ on it.” He pauses. “That’s when I felt it. Felt all of it. Got my head turned inside out.” He then shouts at Bridger for scratching his knife across a canteen, the noise an echo of his mental perturbation.

In an interview, screenwriter Mark L. Smith explained how he interpreted Fitzgerald:

“He’s a trapper who has survived a Native American attack earlier in his life, and so he’s kind of partially scalped. He’s someone who is—he’s almost driven by fear in a lot of ways … because he’s always worried about something bringing the next attack on him. … He’s not really a villain at the beginning. He’s not a great guy, he’s not a guy that you’d want to hang out with, but some of his logic makes sense.”

Survivors might be portrayed as gruesome novelties, but they were also intended to spark solicitude in nineteenth-century readers, with their scars implicitly justifying the extremes of their Indian-hating violence. Similarly, Fitzgerald is both the clear antagonist of The Revenant—villainous in his abandonment of another white man to the wilderness and his murder of that man’s son—and sympathetic, even if in limited fashion, due to his scarred past and his tenuous present.

Late in the film, Fitzgerald becomes the scalper, as well as the scalped. Having killed one of his pursuers, he unsheathes a knife and takes the man’s scalp: his dexterity as a fur trapper now deployed on humans. While his action could be explained as an act of misdirection—making the murder look like it was done by hostile Natives—it seems clear that Fitzgerald performs the scalping as instinctive, feral act. The film has by this point long made its argument apparent through literal signposting: the men invading the West, a placard proclaims, are “all savages” (“on est tous les sauvages”). Yet such rhetoric is diluted by The Revenant’s insistence that some white men (Glass, Bridger, Captain Henry) possess a fundamental decency that belies their grime. Fitzgerald and the “Ree,” on the other hand, share the suspect status of those who scalp and are scalped: persons who might become hairy objects, not unlike the furs bundled on a trader’s back.

The real-life inspiration for Fitzgerald was not a scalping survivor, nor, as far as anyone can tell, was he uniquely depraved—just a man who made the ethically dubious but not unheard-of decision to abandon a wounded colleague. Yet The Revenant’s screenwriters chose to imagine him as a survivor. Why? In part, no doubt, because the film draws heavily on period source material and insists on a type of historical authenticity, even as the characters and plot are thoroughly Hollywood-ized. That insistence on accuracy, ironically, leads the film to rely on sources that fictionalized the very real suffering of such individuals in order to make arguments about Native savagery and eliminationist American policy. The film follows an old script: its vaunted attention to detail and sympathetic treatment of Native characters notwithstanding, it never fully interrogates the underlying assumptions and premises of nineteenth-century accounts. While the Indian-hating words and deeds of a character like Fitzgerald clearly mark him out as the baddie for contemporary film-goers, The Revenant does not, ultimately, ask audiences to reconsider their relationship to settler colonialism. Indeed, Fitzgerald’s scars are explained as the source of his antagonism, not as a response to it.

Fitzgerald, too, is a “revenant,” “a man raised from the dead” like the historical scalping survivors he is modeled upon. Despite the film’s apparent goal of providing a more nuanced picture of America’s imagined frontiers, The Revenant throws away an opportunity to take a nuanced look at the trauma and violence upon which the West was built, settling instead for repeating the tropes of its nineteenth-century source materials: white Americans facing and overcoming adversity in the wilderness. Fitzgerald’s hatred is given a rationale, even as he’s condemned for it. Displacing all American vulnerability onto Fitzgerald, and making him the villain as a result, lets the film avoid true acknowledgment of the vulnerability—and savagery— of the entire project of settler colonialism. Fitzgerald’s weakness is exposed only to be disavowed: his wickedness and woundedness are intertwined, the story implies, and the West will ultimately belong to those, like Glass, who take back their fates from the hands of others.

Acknowledgements

This essay grew out of the final assignment for a course I taught in Spring 2016, “Imagining the Indian: Native Americans on Page and Screen.” Having (perhaps rashly) promised my students that I, too, would complete my own assignment, I owe them many thanks for their thoughtful discussion of an initial draft. I’d also like to thank Ansel Payne, Laura Helton, Samantha Seeley, the members of my faculty writing group at the University of Alabama, and the editors at Common-place for their critiques and advice.

Further reading

For more on the real Hugh Glass, as well as the popularity of frontier narratives in the early nineteenth century, see Jon T. Coleman, Here Lies Hugh Glass: A Mountain Man, a Bear, and the Rise of the American Nation (2012). An influential example of such narratives, James Hall’s Sketches of History, Life, and Manners, in the West (1835), appears to have been the inspiration for the “metaphysics of Indian-hating” section of Herman Melville’s The Confidence-Man (1857).

For the story of David Hood and other scalping survivors in early Tennessee, see A.W. Putnam, History of Middle Tennessee, or, Life and Times of Gen. James Robertson (1859) and Edwin Paschall, Old Times, or, Tennessee History: for Tennessee Boys and Girls (1869), among others. For another example of conflicting accounts of a survivor’s mental and physical recovery, compare the versions of James Gregg’s Revolutionary-era scalping in two nineteenth-century recountings: The Child’s Picture Book of Indians… By a Citizen of New-England (1833) and “Adventure of Captain Gregg,” John R. Chapin, “Indian Tales,” unbound sheets from Chapin’s Historical Picture Gallery (1856).

For a different take on the role of scalping in American storytelling, see Gordon M. Sayre, “‘Take My Scalp, Please!’: Colonial Mimetism and the French Origins of the Mississippi Tall Tale,” in Matt Cohen and Jeffrey Glover, eds., Colonial Mediascapes: Sensory Worlds of the Early Americas (2014) for an analysis of tales where European travelers claimed to have outwitted antagonistic Native Americans by pretending to pull off their own scalps.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.1 (Fall, 2016).

Mairin Odle is assistant professor of American Studies at the University of Alabama. She is currently working on a book which explores how cross-cultural body modifications in early America remade both physical appearances and ideas about identity. Focusing on indigenous practices of tattooing and scalping, the book traces how these practices were adopted and transformed by colonial powers.