We the People

It was a frigid cold afternoon in February 1988 when I first took students to participate in the district level competition at Syosset High School, Long Island, New York, of the “We the People” program on the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. “Be confident in yourselves,” I told my high schoolers during the long bus ride, as they anticipated stepping on stage to join a simulated congressional hearing. “You can speak eloquently about how the founding of our nation has been an adventure in ideas.” One student, in his youthful enthusiasm, laughed, “This is America, baby. We want to win.” His remark was a reflection of the healthy competitiveness that the program’s course of study promotes. Yet the competitive spirit is grounded in cooperation, for the students have to work together in teams to develop their ideas in depth on a specific topic. “We the People” (formerly known as the Bicentennial Competition on the Constitution) was founded in 1987, chaired by former Chief Justice Warren Burger, and is conducted by the Center for Civic Education. Its premise is that what defines us as a nation is the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights; we are held together by our shared beliefs in the values of liberty, equality, and justice. Students begin a six-month program by studying the text We the People: The Citizen and the Constitution, whose topics include:

- What were the philosophical and historical foundations of the American political system?

- How did the Framers create the Constitution?

- How did the principles and values embodied in the Constitution shape American institutions and practices?

- How have the protections of the Bill of Rights been developed and expanded?

- What rights does the Bill of Rights protect?

- What are the roles of the citizen in American democracy?

The classroom lessons are supplemented by in-depth study of each of the units. Students are divided into six groups of three or four each (depending on the size of the class). Each of the groups prepares a four-minute opening speech on each of three questions. The opening speeches are presented at a district/regional competition in January; the opening remarks are followed by a six-minute questioning period on the specific topic and the overall knowledge of the course. The students must work cooperatively on developing the opening speeches and answering the follow-up questions. Each unit is judged on the following criteria:

- Understanding

- Constitutional application

- Reasoning

- Supporting evidence

- Responsiveness

- Participation

The class that wins the most points will be eligible to compete at the state level. It sounds complicated but it works extremely well. Let’s follow Unit One from the classroom lesson to the simulated hearing at both the district and state levels. The three questions for preparation in Unit One are:

- How were the Founder’s views about government influenced by both classical republicans and natural rights philosophers?

- What are the fundamental characteristics of a constitutional government?

- What effect did colonial experiences have on the Founder’s views about rights and government?

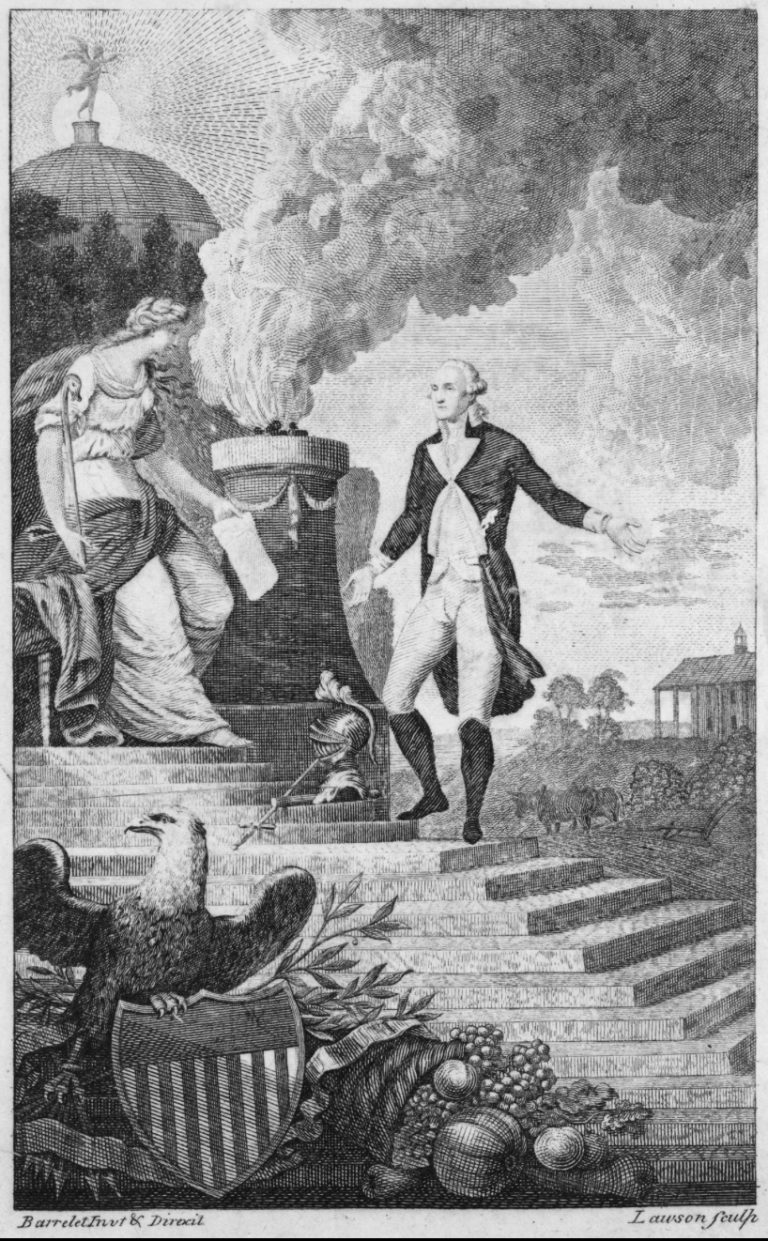

Classical republicanism is a difficult topic for students to understand and so the classroom lesson focused on the story of Cincinnatus and civic virtue. John Barralet’s engraving, General Washington’s Resignation, was distributed to students and analyzed in connection with the Cincinnatus story.

In class discussion, I asked my students what “the plow awaits the plowman,” meant. Where is George Washington’s hand pointing and why? What is Lady Liberty offering him? How does he respond? How do his actions illustrate the story of Cincinnatus? How are his actions a major tenet of classical republicanism? How does classical republicanism shape contemporary political culture? Many students feel that it is an outdated idea. “It’s positively frightening,” one student remarked, “because one has to sacrifice his rights for the common good. Who can determine the common good? How do we know what it is?” “Perhaps,” said another student, “George Washington was fulfilling his own power struggle and not really sacrificing power for the common good.” Another student disagreed, pointing out that Washington gave up the presidency after two terms. “Who gives up power? He must have been acting on the principles of classical republicanism.” A slightly different debate went on at the congressional hearing where this question was called. The students were asked why classical republicanism held that military service was important and whether they thought military service should be mandatory. Students understood the concept of citizen-soldier because of the classroom discussions and their in-depth study of the situation. However, the unit members disagreed among themselves as to whether military service should be mandatory. One student asserted, “Classical republicanism is not relevant today. Citizen-soldiers preparing to defend their country is an outdated idea. We are at the hands of the politicians who get us into war without our consent and this would encourage them. We have a professional army and that is all that is needed. Besides, technology reduces the need for a required draft as most fighting will not be person-to-person combat.” Another replied, “I think our country is stronger if each person is prepared to defend it and gives up time in their life to answer the call of good citizenship. We have been too focused on our individual rights and we are becoming selfish.” After winning the regional competition, the students confronted still different questions at the state level:

- According to the natural rights philosophers, under what circumstances are people justified in exercising their right of revolution?

- What is the importance of the rule of law in a constitutional government?

- How were governments in colonial America similar to or different from the government in England at the time?

In discussion, students were asked a question following up on the first above: Did southerners misuse the Declaration of Independence when they seceded from the Union? The first student to speak spoke forcefully: “They used it correctly. They felt that their liberty was taken away when a president was elected without their consent. Abraham Lincoln did not get one vote from the South.” A second respondent agreed, “We may not like it, but they used it correctly. They established conventions and asked the people to vote for secession. They felt that their property was going to be taken away. After all, the Republican Party platform was illegal in that it went against a Supreme Court decision.” Finally, a third student countered, “They used it incorrectly. It just goes to show you how a leader can manipulate the mob. Madison wanted a Constitution just to avoid mob manipulation at the local level. These people were not defending equality or liberty but slavery.” I’m proud to report that my class won the New York State championship that year, in 1988. (Indeed, I’m delighted to report that my classes have won the state championship in nine of the thirteen years that I’ve participated in the competition.) The national competition, at which there is a team from every state, follows much the same format. At this competition, held in Washington, D.C., two questions are called in the first two days. The totals of the two-day competition will determine the ten classes nationwide that will compete on the third day for the top three spots nationwide. The judges at the national competition, held in the Senate hearing rooms, are usually very prominent officials–constitutional scholars, law professors, justices, and government officials. Take a look at how the Unit One questions and answers changed during the national competition:

- Rights and republican self-government may be said to be the twin pillars of the American political tradition. These pillars are planted in the soil of our history so firmly and seem to reinforce each other so strongly, that it is hard for us at first to credit any suggestion that there may be some tension or problem in their coexistence. Should these two Rs be considered the twin pillars of our political tradition? Why or why not?

- In his classic study of the influence of the frontier on American history, Frederick Jackson Turner observed that “American democracy was born of no theorist’s dream; it was not carried in the Susan Constant to Virginia, nor in the Mayflower to Plymouth . . . free land and an abundance of natural resources open to a fit people, made the democratic type of society in America.” Do you agree or disagree with Turner’s statement? Explain your position.

- The experience of the American Revolution influenced the constitution making that followed Independence. Which lessons learned from the colonists’ break with Great Britain were positive? Which lessons turned out to have been wrong? Which lessons proved to be temporary? Which have survived to the present day?

The Washington experience is one that my students never forget. They remember the discussions, the opening speeches, the dialogues and the camaraderie as the best experience in high school. They make friends with students from all over the country and they keep in touch. They even meet some of them at their respective colleges. There were other discussions to remember besides the ones surrounding natural rights and classical republicanism. Students debated the constitutionality of Bush v. Gore, the power of the Supreme Court, and whether the Bill of Rights is as Madison said, “merely a parchment barrier.” On that frigid February day in 1988, my elated students won the regional competition. They went on to win the New York State championship and came in third in the United States. However, they achieved more than that. They forged a cooperative spirit in working together to plan ideas, they practiced public speaking, and they became critical thinkers, highly knowledgeable about the foundation of the “idea” that is American democracy. They practiced civic responsibility and they learned the values of good citizenship. They are still friends today and the student who once said, “This is America, baby. We want to win,” will be clerking for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg next year.

This article originally appeared in issue 2.4 (July, 2002).

Gloria Sesso is district director of social studies for the Patchogue Medford School District and was the teacher and coach of the “We the People” class and team at Half Hollow Hills East for thirteen years. Patchogue Medford is currently instituting the “We the People” program in its high school.