What He Did For Love: David Claypoole Johnston and the Boston Irish, 1825-1865

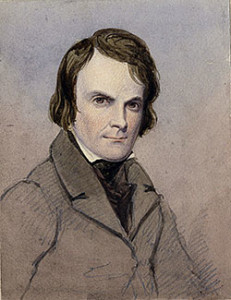

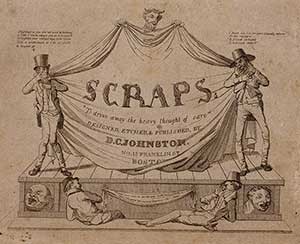

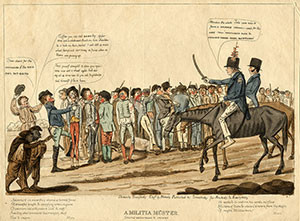

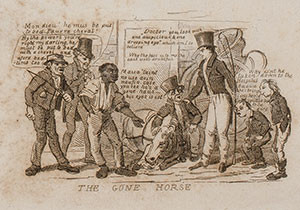

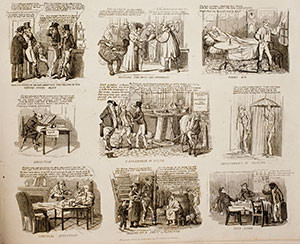

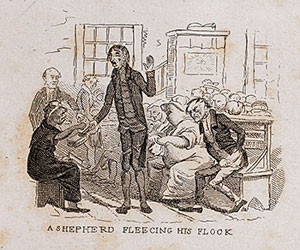

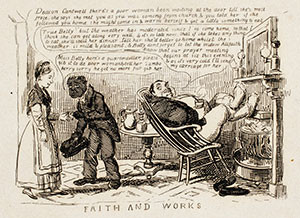

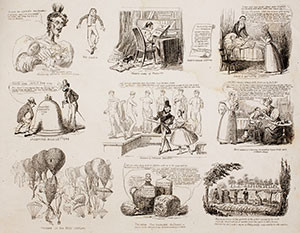

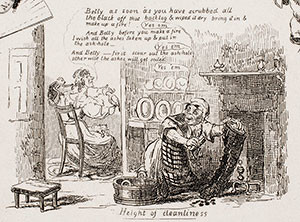

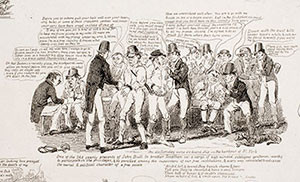

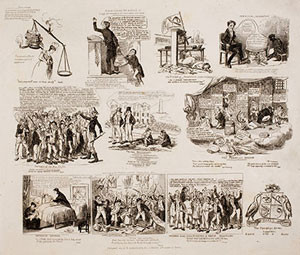

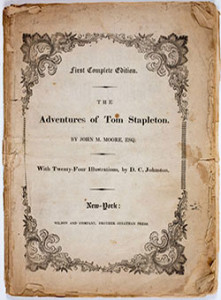

David Claypoole Johnston was an engraver, artist, and satirical commentator on American life, who can reasonably be called the best known and most popular American graphic artist of the first half of the nineteenth century (fig. 1). Born in Philadelphia, he apprenticed there, and moved to Boston in 1825, living and working in the city until his death in 1865. The cartoons, prints, and yearly satiric periodicals on which his contemporary reputation as “the famous caricature designer” rested were advertised, editorially noted, and sometimes extensively reviewed in the Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Baltimore and Charleston newspapers. Their circulation reached considerably farther—throughout the smaller cities of New England (Portland, Portsmouth, Providence, and Hartford)—and at times to Savannah, Cincinnati, and New Orleans. Love and marriage pulled this Protestant artisan and satirist, born into a family of performers, into the orbit of Boston’s tight-knit yet marginal Irish and Catholic community.

David Claypoole Johnston was no Irishman, but he married into the clan, and thereby hangs this tale. His own ethnicity was Scottish and English. Born in Philadelphia in 1798, he was the child of an Englishwoman, the young former actress Charlotte Rowson (the sister of the author Susanna Rowson), and William P. Johnston, an accountant, bookkeeper, and devotee of the stage, whose ancestors had come to New Jersey in the early eighteenth century from southern England and from Edinburgh in Scotland. Charlotte had been baptized in the Church of England, and by the mid-eighteenth century, members of the Johnston family were being married in the Anglican Church and buried in the Anglican cemetery. Indeed, Johnston’s great-grandfather, a Scotsman born in Edinburgh, had sought out the Anglican rather than the Presbyterian church when he arrived in his new homeland.

After their marriage, William and Charlotte became parishioners of old St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. Given Philadelphia’s high ethnic diversity by early American standards, David would have known a number of people of Irish descent, and more than a few Catholics; working as he did in the book trades, he surely would have known of, and perhaps met, the great publisher and printer Matthew Carey, the city’s most famous and successful Irish Catholic. Johnston’s master in the engraving trade, Francis Kearny, was himself the descendant of Irish Catholics who had come to New Jersey, but his family had shed its ancestral faith within a generation, also becoming Anglicans.

There is no reason to suspect Johnston of piety in his early life. He was a caricaturist from the time he could hold a pencil, and in his youth an accomplished mimic, an amateur musician with a predilection for comic songs, and as he recalled, “a nice man for a party.” His autobiography makes no mention of religious feeling or religious matters, and none of the work that he produced in Philadelphia between 1815 and 1825 had any religious content. Out of this religious genealogy, we can draw at least one conclusion: there is no evidence of any strain of Calvinist, Reformed, or Evangelical sentiment in Johnston’s background.

Human love, not a wrenching religious conversion or spiritual journey, determined Johnston’s trajectory. In this, he followed the path of his parents. Smitten by her appearances on the Philadelphia stage, William Johnston had pursued the eighteen-year-old Charlotte Rowson to Boston when her family had moved there to open the city’s first theater in 1797. He proposed, married her in Boston, and brought her back to his native city. Charlotte retired from the stage, but William maintained some involvement in theatrical business affairs in Philadelphia, eventually becoming treasurer of the Chestnut Street Theater. David, their oldest son, himself took a turn on the professional stage; as a young engraver looking for additional income, he spent three seasons as a part-time actor in Philadelphia and Baltimore.

In 1825, David Johnston moved to Boston, looking for a better reception from the city’s publishers than he had received in his turbulent early years in his home city. Shortly after his arrival, Johnston became a boarder at the Irishman Thomas Murphy’s well-known establishment on Federal Street—a seemingly small step that would prove momentous. The house was convenient to the Federal Street Theatre, where Johnston had “engaged with the Boston managers” for a year to finance his transition between the publishing worlds of Philadelphia and Boston. At that time, he met Murphy’s daughters, Mary Priscilla, then 17, and Sara Elizabeth, then 15. He seems to have been accepted quickly as a member of the household, to judge by a birthday acrostic he composed for Mary Priscilla in 1826. His theatrical background, which would have rendered him somewhat marginal in the eyes of most residents of respectable Boston households, and disqualified him from social contact with their young women, did not seem to have mattered.

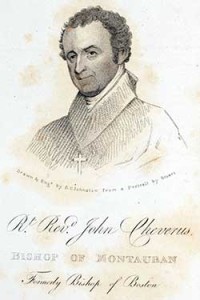

Thomas Murphy had joined the campaign of the United Irishmen in County Wexford in the 1790s, and came to Massachusetts around 1798 after the crushing of the rebellion. Adapting well to his new country, despite the seemingly unpropitious religious climate of Massachusetts, he had become a prosperous innkeeper and then a boarding house proprietor in Concord, Woburn, and finally in Boston. He was a true pillar of both his community and his church: president of the Charitable Irish Society, founder and officer of the Vincent De Paul Society, the Roman Catholic Charitable Relief Society, and the Irish Orphans Annual Fair. His boarding house was a block or two from the Federal Street Theatre; far more important, it was next door to the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, “the first house below the Catholic Church” as his advertisements always said. Priests were always traveling between the Bishop’s seat and their scattered flocks in the far-flung Boston diocese, which until 1843 covered all six New England states. Visiting priests were surely often part of Murphy’s extended household. Both proximity and devotion made Thomas Murphy an important layman.

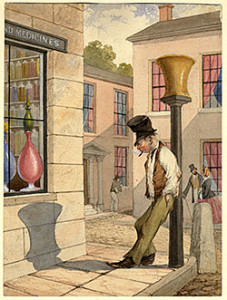

By the end of the theatrical season of 1825, Johnston was able “to cut the boards,” as he put it, to go back to “cutting copper.” His plan to use the theater as a bridge to full-time engraving had succeeded. He “became known to the book publishers,” and opened a shop at 81 Washington Street, where his “abilities were more than appreciated” and “liberally rewarded.” Despite his growing success, Johnston did not leave the boarding house. In fact, he would never leave the Murphy household. Smitten by a beautiful young woman, as his father had been, David patiently courted Sarah Elizabeth, and married her in 1829, just after her nineteenth birthday; he was thirty-one.