What is Evans-TCP?

The Common-place Web Library reviews and lists online resources and Websites likely to be of interest to our viewers. Each quarterly issue will feature one or more brief site reviews. The library itself will be an ongoing enterprise with regular new additions and amendments. So we encourage you to check it frequently. At the moment, the library is small, but with your help we expect it to grow rapidly. If you have suggestions for the Web Library, or for site reviews, please forward them to the Administrative Editor.

Molly O’Hagan Hardy serves as the Digital Humanities Curator at the American Antiquarian Society under a public fellowship from the ACLS. She holds a PhD in English from the University of Texas at Austin.

What is Evans-TCP?

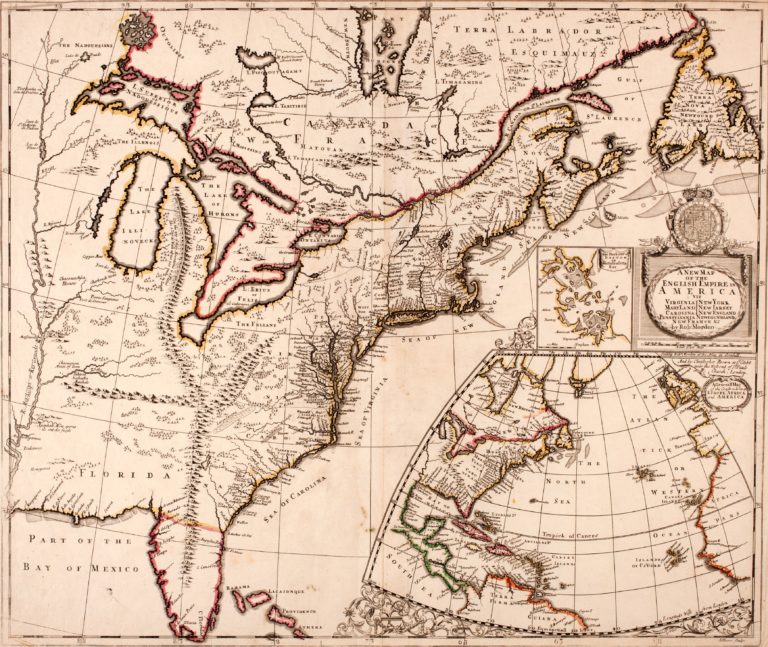

Evans-TCP was a partnership among the Text Creation Partnership (TCP), NewsBank/Readex Co., and the American Antiquarian Society (AAS) that, between 2003 and 2009, created almost 5,000 accurately keyed and fully searchable SGML/XML text editions of early American printed books and pamphlets. The impetuses behind this collaboration were manifold: to increase the readability of early American texts, to make full and corrected texts available for digital projects, and to make searching more accurate because the texts have been corrected. In other words, actual people have typed every word of the selected texts, rendering a much higher degree of accuracy than the optical character recognition (OCR) software that Readex relies on to transform the scans of pages into words. Not only are searches of such texts more reliable, but through Evans-TCP, a user can see the keyed-in text that she searches. When working in the Readex database, a user sees only the image of the original text that has gone through OCR software, but not the text that is being searched. In contrast, the views of the page images are lost in Evans-TCP, but the text is all there. Moreover, in Evans-TCP, a user has access to the XML file, the keyed and encoded texts. Evans-TCP offers a full explanation of its encoding practices, which for the most part are light and invite additions for scholarly digital editions. One caveat about Evans-TCP encoding: for those interested in illustrations of early American texts, it is worth noting that the encoding of images has been minimal. Editor Sarah Winger explains, “This is essentially a compromise: the primary objective for TCP is to create searchable texts. However, we recognize that illustrations, too, are important to a text and can add meaning. The editors account for this by notifying viewers that an illustration is present by capturing useful text associated with it, and by describing it when feasible.”

How can I find out which early American texts are included in the TCP?

In consultation with a number of interested parties, AAS selected which titles within the date range of 1640-1800 would be chosen for Evans-TCP. Needless to say, this selection process was a tricky one. In 2004, a group of ten professors from across the country; eight librarians from AAS, Yale University, the University of Minnesota, and the Boston Library Consortium; two members of the TCP staff; and two Readex staff met to discuss how the selection process would work. The group decided that Evans-TCP would include only first editions unless there was a reason to do otherwise, and that certain categories of imprints would be excluded (e.g., almanacs, heavily illustrated works, music, and non-English language imprints). Works were drawn from selective bibliographies, including Charles Evans’s American Bibliography and Clifford Shipton and James Mooney’s Short-Title Evans, and Jacob Blanck’s Bibliography of American Literature. The following subject headings were also used to select titles from the AAS catalog: Blacks as Authors, Currency/Money/Banking, Indians, Preaching, Salvation, Slavery, Society of Friends, Trials, and Women as Authors. And the following genre headings were used to select titles from the AAS catalog: Anthologies, Broadsides, Captivity Narratives, Memoirs, Novels, Sermons, Songsters, Travel Literature, and Treatises.

The Evans-TCP page offers a number of search options to navigate through these titles: simple, Boolean, proximity, citation, and browsing. The searching is fairly intuitive, but if you need help, check out these instructional videos (though they were creating for EEBO-TCP, the interface is pretty much the same). The browse function is an especially useful way to navigate the collection; browsing can be organized by author’s last name or by title of the work, and it is a good way to get a sense of what is there.

The AAS general catalog is another way to find texts in Evans-TCP. On the upper right side of the screen in an AAS catalog record a user will see a link to any title included in Evans-TCP. When conducting a keyword search in the AAS General Catalog, include “Evans TCP” as a phrase to generate a complete list of records with such a link in it. Or, include other search terms to find out if imprints you are interested in are included in Evans TCP.

Who can access the TCP and how does access work?

This is the really great news: as of June 30, 2014, anyone anywhere has access to the Evans-TCP texts. As was mentioned above, TCP welcomes requests for source files for individual texts, or the whole corpus of its titles. After the June release date, anyone will be free to access and make use of these raw files through an online directory where they can be downloaded. Rebecca Welzenbach, TCP outreach librarian at the University of Michigan, explains, “Our intention is to make them available in such a way that people can find and download them without having to come through us.” Welzenbach does offer one reminder: although TCP includes links to the Readex/Newsbank page images, these will not be publicly available. The TCP makes XML encoded transcriptions, not the whole database, available. It is, however, transcriptions such as these upon which so much digital humanities work from the early modern period to the nineteenth century relies.

What can I do with Evans-TCP texts?

Because the Evans-TCP texts include only about 5,000 imprints before 1820, its corpus is less than ideal for large-scale text mining projects, but it could still be used for single text or author data analysis, or the building of digital scholarly editions, or for pedagogical purposes (many of the titles in Evans-TCP have not been republished in modern editions for the classroom). But we assume that there are ways for early Americanists to make use of this incredible resource that we haven’t even thought of yet.