What’s in a Name

How Durben in Glasgow Became Dearborn in Quebec

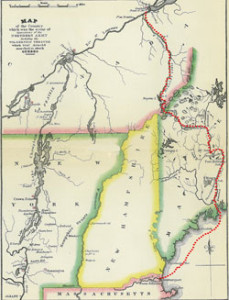

I discovered a Revolutionary-era journal written by a Captain Durben—from an unexpected source—in 2009 while researching Benedict Arnold’s expedition to Quebec, a disastrous 1775 attempt to invade Canada and capture the city for the American cause. One of my primary purposes at that time was to compile a comprehensive bibliography of all printings of every journal written about the Arnold expedition, which seems to have generated more journals than any Revolutionary War battle.

One of many Google searches took me to a surprising entry, featured in an online Americana exhibit created by the Special Collections Section of the University of Glasgow Library, which was devoted to eighteenth-century books and manuscripts. On the fourth page, I found a description of a manuscript titled, “A Journal of the Rebel Expedition,” written by a Captain Durben, along with an image of the journal’s first page. The subtitle stated that this was “An exact copy of a Journal of the Route and Proceedings of 1100 Rebels, who marched from Cambridge, in Massachusetts Bay, under the Command of General Arnold, in the fall of the year 1775; to attack Quebec.” I was immediately intrigued—this document purported to be a manuscript journal of the Arnold expedition that had previously been entirely unknown to me.

Upon reflection, I was astonished that an unknown journal of an important Revolutionary War event had been residing in a university library in Scotland for over 225 years and had never been mentioned in any scholarship on the Revolutionary War. At the same time, I was also skeptical. How did a manuscript journal written by an American officer end up in Scotland? Moreover, I had done enough research on the Quebec expedition to know that there was no American officer involved named Durben. The more I thought about the online exhibit, the more I was convinced that, when I researched it further, the manuscript would turn out to be a disappointment because it would prove not to be an original journal of the expedition to Quebec.

I was immediately intrigued—this document purported to be a manuscript journal of the Arnold expedition that had previously been entirely unknown to me.

The Durben manuscript was contained in a bound volume entitled “Manuscripts from the Library of William Hunter.” Dr. Hunter was a Scottish physician and private book and manuscript collector so active in his era that he was a competitor of the British Library. At his death in 1783, he bequeathed his collection, including the Durben journal, to the Library of the University of Glasgow.

I wrote to the Special Collection librarians there, requesting a photocopy of the manuscript journal. They readily copied the entire file and sent it to me. The package included the Durben journal plus two other, shorter journals of the expedition. No author is identified by name for either of these shorter journals.

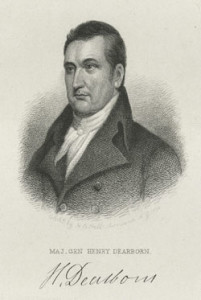

After closely examining the Durben manuscript, I concluded that it was a period copy of a previously unknown journal originally authored by Captain Henry Dearborn (1751-1829) of New Hampshire, probably one of the best-known officers on the expedition other than Arnold himself. Dearborn was captured in the assault on Quebec on December 31, 1775, and was imprisoned in Quebec until he was released on parole early in May 1776. The journal entries cover the period September 13, 1775, through May 18, 1776. These entries were written contemporaneously as events occurred, as the author went along on the expedition and then, during the winter of 1775-1776, when he was imprisoned in Quebec. The transcription was evidently penned sometime thereafter, by Dr. Robert Robertson (1742-1829), a Scottish surgeon serving with the Royal Navy in Quebec in 1776. In what follows I’ll discuss the evidence that led me to these conclusions.

The name “Durben” at first threw me because, as mentioned above, there was no officer in the Arnold expedition with that name. Looking at names that might sound like Durben, I tentatively concluded that the author might be Captain Henry Dearborn. No other officer had a name that sounds anything like Durben, and no other officer’s name begins with the letter “D.”

Two entries in the journal provided additional evidence supporting Dearborn’s authorship. The author mentions two of his officers by name, both of whom were in Captain Dearborn’s company. The first is Joseph Thomas, who was appointed as Dearborn’s Ensign, according to the daily entry for September 18. The author also refers in an entry on November 2 to a Lieutenant Hutchins being in his company. Both Joseph Thomas and Nathaniel Hutchins were officers in Dearborn’s company, and both are listed in New Hampshire Troops in the Quebec Expedition, published by the state of New Hampshire in 1885.

The Durben journal concludes with entries for the days of May 17 and 18, 1776, which describe the author leaving on a boat with Major Return J. Meigs. The early exit from Quebec by the two officers, Meigs and Dearborn, is verified by other expedition journals, providing compelling supportive evidence that the author of the Durben journal was Henry Dearborn. In Private James Melvin’s journal, the entry on May 18, 1776, reads: “Pleasant weather; hear that Major Meigs and Captain Dearborn are gone home.” There are also two entries in Captain Simeon Thayer’s journal: “May 17 … Major Meigs had the liberty to walk the town until 4 o’clock. Mr. Laveris came and informed Capt. Dearborn that he had obtained liberty for him to go home on his parole … May 18. About ten o’clock they [Meigs and Dearborn] set sail for Halifax.” It is clear from these entries that it was well known by the men in prison in Quebec that Meigs and Dearborn went home together.

A note located at the end of the “Captia” portion of the Durben manuscript describes how the journal came into the hands of its transcriber. Here, the writer recounts that Meigs and Dearborn went on board the schooner that was to take them to Halifax on May 17, but it did not make it out of the harbor and had to return. It ended up sailing again the next day, but in the intervening period the journal was stolen from Dearborn. “By some accident or another, the Schooner that they sailed in was obliged to return to Quebec; and a person on board of her stole the originals from the author, & gave it to one of his own friends a shore, who was so obliging as to lend it to me to take a copy of it—at least this is the history which I got from that gentleman, of it.” It is clear from this information that Dearborn wrote this journal prior to May 17, 1776.

At the bottom of page 1, Dr. Hunter writes that the journal was given to him by a Mr. Robertson, whom he describes as a surgeon on HMS Juno. Documents held at the University of Glasgow identify the Juno as a “32-gun ship launched in 1757” and “a fifth rate shipping frigate which was burnt on 7 August 1778.” Entries in Naval Documents of the American Revolution confirm that Dr. Robertson was on board the Juno. The frigate arrived in Quebec on June 4, 1776, five months after the assault on Quebec and two weeks after Meigs and Dearborn left Quebec aboard the HMS Niger. Thus, Dearborn was long gone from Quebec when the journal made its way to Robertson via an unknown third party who had stolen it from its original author.

A little over two years later, on August 7, 1778, the Juno was burned in Providence Harbor to prevent its capture by American forces. Since Robertson was not listed as a surgeon on any other ship after 1778, it is reasonable to conclude that he was not on the Juno when it was destroyed, or else he would have been transferred to another ship. I believe it is likely that Robertson transcribed Dearborn’s original manuscript journal while he was on board the Juno, between the time it left Quebec in September 1776 and August 13, 1777, the last known date he was on board.

Dr. William Hunter, the subsequent recipient of the manuscript, died on March 30, 1783, and from his signed notation in the journal we know that it was in his hands before he died. Thus, sometime between 1777 and 1783 Robertson apparently gave his transcribed copy of the journal to Hunter. It has been in the Hunter manuscript collection since that time, and at the time I discovered it had never before been published.

What we have, then, is a journal dating back to 1775, written originally by Henry Dearborn. This original journal was subsequently stolen from its author, transcribed and edited by Robertson, and then given to Hunter. The original manuscript in Dearborn’s handwriting has long since disappeared, or at least its whereabouts are unknown.

After the Quebec experience, Dearborn went on to an impressive military career during the Revolution, participating in the battles of Saratoga, Monmouth, Sullivan’s campaign, and Yorktown, ending as a lieutenant colonel. After the war, Dearborn was appointed a major general in the Maine state militia, a United States marshal in Maine, and was elected to Congress. In 1801, President Thomas Jefferson named Dearborn Secretary of War, and during the War of 1812 James Madison appointed him Senior Major General in the Army, in command of the northeast sector. From 1822 to 1824, he served as Minister Plenipotentiary to Portugal, and he died in Roxbury, Massachusetts, in 1829.

Henry Dearborn is known to have written five other journals of his Revolutionary War experiences, all of which survive in manuscript form. Four of these are in Dearborn’s handwriting. The last discovered journal, covering the march to Quebec, survives at the Boston Public Library (BPL) and was published in the Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1886. According to John Wingate Thornton, a nineteenth-century antiquarian and an expert on handwriting, this last journal held at the BPL is not in Dearborn’s handwriting, although he did make some corrections to the manuscript in his hand. In order to better compare the two journals, I spent a day reviewing the manuscript in Boston.

Comparing the Glasgow journal with the one published by the Massachusetts Historical Society, it is easy to see that many of the entries and the events that are covered are similar. However, the Glasgow journal is shorter and more succinct in its entries, which lends credibility to the conclusion that it was written during the events discussed. It is much more likely that someone writing during a significant army field maneuver would not have time for the more extensive and flowery descriptions that are found in the later journal.

An example of the differences in the two journals can be found in the entries for September 22, 1775. The Durben journal entry reads:

22nd. We got up where the Bateaux were built; from thence we carried thirty three men of each Company in the Bateaux up to Fort Western; That is about forty miles up from the mouth of the River; and at night all our men had mostly got up to the Fort.

The MHS journal entry expands the account:

Septemr 22d. Proceeded up the River. We pass’d Fort Richmond at 11: O clock where there are but few Settlements at Present, this afternoon we pass’d Pownalborough, Where there is a Courthouse and Gaol—and some very good Settlements, This day at 4 O Clock we arrived at the place where our Batteaus were Built.

We were order’d to Leave one Sergeant, one Corporal and Thirteen men here to take a Long the Batteau’s, they embarked on Board the Batteaus, and we proceeded up the River to Cabisaconty, or Gardners Town, Where Doctor Gardner of Boston owns a Large Tract of Land and some Mills, & a Number of very good dwelling Houses, where we Stayed Last night, on Shore.

Another even more significant variation is found in the comparable entries for October 4, although it is not clear if the same events for that day are being described in the two accounts.

The Durben journal entry records: “4th. We haled [hauled] up our Bateaux at the Portage, and dried them.”

The MHS entry states: “4 Our Course in general from the mouth of the river to this place has been from North, to North East, from here we Steer N.:W. to Norrigwalk, which is Twelve miles to where we arrived to night, the River here is not very rapid. Except Two bad falls, the Land on the North side of the river is very good, where there are 2 or 3 families settled, at Norrigwalk, is to be seen the ruins of an Indian Town, also a fort, a Chapel, and a Large Tract of Clear Land but not very good, there is but one family here at present Half a Mile above this old fort, is a Great fall, where there is a Carrying place of one Mile and a Quarter.”

The missing Quebec expedition journal in Dearborn’s own handwriting is an obvious omission in the personal accounts of his Revolutionary War experiences. Until now, it was thought that the original manuscript journal written at the time by Dearborn was the one published by the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1886—although not in his handwriting. Now, however, we know better, because we have that original journal, or at least a sanitized version of it, from the late eighteenth century.

Finding Henry Dearborn’s original journal has been exciting and rewarding in ways I could not have predicted. I am convinced that had I not followed through on tedious Google searches, this journal would have never been discovered and made public. As Revolutionary War manuscripts go, this one is not earth-shattering, nor does it contain any momentous revelations that will change the history of the invasion of Canada. But in its own right it is a significant finding that clarifies the history of one participant’s own narratives of the war, and presents the original version of an account that has been known only through later revisions.

After Benedict Arnold himself, Henry Dearborn was the most famous military man on the expedition to Quebec, and he was one of only a handful of American officers to write a journal covering the entire period of the Revolutionary War. Moreover, Dearborn’s subsequent career was unmatched by any other participant in the expedition. By virtue of his appointment as Senior Major General during the War of 1812, he rose to a higher military rank, and as congressman and Secretary of War, he attained a higher civilian position than any other expedition alumnus except for Vice President Aaron Burr. Discovery of the Dearborn journal also reveals a fascinating story about how an American manuscript made its way to from Quebec to Scotland, where it has been unknowingly preserved for over 200 years.

To date, I have succeeded in identifying thirty-three extant journals of the Quebec expedition, including the three found in the University of Glasgow Library. When I started this journey, I did not expect to find any previously unknown and unpublished journals, particularly in Scotland. Much to my surprise, there are still unknown manuscripts to be found in the unlikeliest of places. I now know that research that starts out in one direction can lead to surprising and unexpected results that are more rewarding than the original objective.

Further Reading:

The complete transcribed Dearborn journal, as well as the two smaller journals, and notes by Robertson and Hunter, can be found in Stephen Darley, Voices from a Wilderness Expedition: The Journals and Men of Benedict Arnold’s Expedition to Quebec in 1775 (Bloomington, Ind., 2011).

To read other journals of the Quebec expedition, see the compilation of thirteen journals by Kenneth Roberts, March to Quebec: Journals of the Members of Arnold’s Expedition (New York, 1946). The best histories of the Arnold expedition are Justin H. Smith, Arnold’s March from Cambridge to Quebec (New York, 1903); John Codman, Arnold’s Expedition to Quebec (New York, 1901), and Thomas A. Desjardin, Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold’s March to Quebec in 1775 (New York, 2006).

There are numerous publications of individual Revolutionary War journals from a variety of battles and campaigns. Two compilations of journals from the war are John C. Dann, ed., The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for American Independence (Chicago, 1980) and George C. Scheer and Hugh Rankin, Rebels and Redcoats (New York, 1957).

For background on Benedict Arnold, the most thoroughly researched biography is James Kirby Martin, Benedict Arnold, Revolutionary Hero: An American Warrior Reconsidered (New York, 1997).

This article originally appeared in issue 14.3 (Spring, 2014).

Stephen Darley is a retired attorney and independent scholar based in North Haven, Conn. He has been conducting research on the Revolutionary War in general, and Benedict Arnold in particular, for over forty years.