What indeed motivates “forgiveness” as a social policy when it is disconnected from admission of wrongdoing and the quest for justice? From the earliest days of his marriage, Beecher learned to treasure the pleasures of looking away from suffering, injustice, and death. His society granted expansive permission for white men to avoid behaving like adult members of a moral community. “Boys will be boys” at the expense of everyone else. The process through which the Confederacy won the peace included a postbellum northern culture where prominent leaders like Beecher fortified misogyny and racism through sanctimonious tropes of evangelical love and forgiveness. Extending facile, unearned forgiveness to self-pitying and unrepentant men, Beecher undermined accountability and justice. He became the flagbearer for an aesthetic and theatrics of gender and race that flirts with maudlin dictatorship.

Further Reading

Debby Applegate, The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher (New York: Doubleday, 2006).

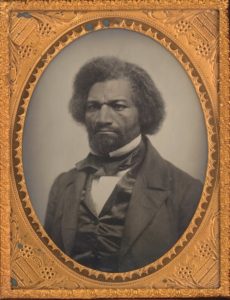

David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018).

David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002).

Barbara Goldsmith, Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1998).

Kate Manne, Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Simon Stow, “Agonistic Homegoing: Frederick Douglass, Joseph Lowery, and the Democratic Value of African American Public Mourning,” American Political Science Review 104, no. 4 (Nov. 2010): 681-97.

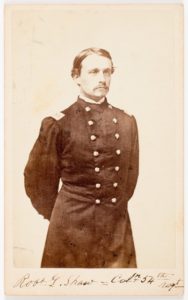

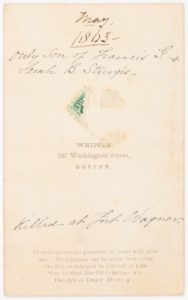

Henry Ward Beecher’s letter to Sarah S. B. Shaw (August 7, 1863) is located at the Boston Athenaeum, Shaw Family Letters received 1859-1940, Mss. .L613. I am grateful for their permission to quote.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s letter to Henry Ward Beecher (Oct. 1866) is in the E. Bruce Kirkham Collection at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Connecticut. The original is at the Sterling Library, Yale University. Lydia Maria Child’s letter to Sarah Shaw (Sept. 7, 1866) is included in Lydia Maria Child, Selected Letters, 1817-1880, ed. Milton Meltzer and Patricia G. Holland (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1982). Additional letters by Lydia Maria Child are collected in A Lydia Maria Child Reader, ed. Carolyn L. Karcher (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997).

This article originally appeared in February 2022.

Kari J. Winter is a Professor of American Studies in the Department of Global Gender and Sexuality Studies at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Her books include The American Dreams of John B. Prentis, Slave Trader; The Blind African Slave: or, Memoirs of Boyrereau Brinch, Nick-named Jeffrey Brace (a scholarly edition of a long-lost 1810 slave narrative), and Subjects of Slavery, Agents of Change: Women and Power in Gothic Novels and Slave Narratives, 1790-1865.