Who Reads an Early American Book?

More people than you might think

Who reads an early American book? The varied list of readers implied by our table of contents suggests several answers to the question posed by the title of this special issue. But consider also the readers, past and present, represented by the history of one curious early American text: the epitaph on the headstone of a Revolutionary-era poet named Elizabeth Whitman, the prototype for the heroine of one of the new nation’s bestselling novels, Hannah Webster Foster’s The Coquette (1797). The thirty-seven-year-old daughter of a Hartford, Connecticut, minister and an associate of the best-known poets of the new nation, Whitman became famous in the summer of 1788, not for her poetry, but for her death, which helped to bring her poetry to a wider audience than she had enjoyed during her lifetime. Whitman died, self-exiled in South Danvers (now Peabody), Massachusetts, having delivered a stillborn child out of wedlock. Her identity became known as a combination of newspaper notices and gossip circulated throughout New England, the mid-Atlantic, and as far down the coast as Charleston, South Carolina. A flurry of newspaper commentary ensued, and Whitman’s story was recounted in the “first American novel,” William Hill Brown’s The Power of Sympathy, early the next year. In the fall of 1789, a little more than a year after her death, Whitman’s Connecticut friends paid for an unusually wordy headstone to be erected in Danvers.

This humble stone, in memory of

ELIZABETH WHITMAN,

Is inscribed by her weeping friends,

To whom she endeared herself

By uncommon tenderness and affection.

Endowed with superior genius and accomplishments,

She was still more distinguished by humility and benevolence.

Let Candour throw a veil over her frailties,

For great was her charity to others.

She lived an example of calm resignation,

And sustained the last painful scene,

Far from every friend.

Her departure was on the 25th of July, A.D. 1788.

In the 37th year of her age;

The tears of strangers watered her grave.

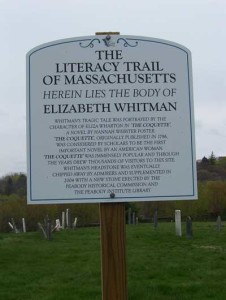

Whitman’s epitaph, which was reproduced with some minor but significant revisions at the close of The Coquette, was one of the most widely reprinted in the nineteenth century. Her grave (like that of the fictional heroine Charlotte Temple in New York City) became a major tourist destination and was also a favorite spot for local youths to become engaged. All this was due in some measure to Foster’s novel, which went through ten editions between 1797 and 1866. Generations of American readers consumed it; grandparents passed it down and told their grandchildren stories about the beautiful, mysterious stranger who died in Danvers; and relic seekers chipped off pieces of her headstone until nothing remained but a soft stump of red freestone with only the last line of the epitaph visible. Some readers in the later part of the nineteenth century even assumed Elizabeth Whitman had provided a model for Hawthorne’s Hester Prynne.

![Elizabeth Whitman's headstone, on the left, damaged by relic seekers, as it has appeared since the late nineteenth century. The new stone, at the right, was installed by the Peabody Historical Commission and Peabody Institute Library in 2004 and mimics the design of Eliza Wharton's headstone in Hannah Webster Foster's The Coquette. Photo courtesy of the Salem News, Salem, Massachusetts. [The photo was used in an article on 24 July 2007]](http://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/9.3.Waterman.1-300x245.jpg)

Many of the strangers whose tears watered Whitman’s grave read an early American book, the one penned by Hannah Foster. Though it eventually fell into obscurity, relegated to a readership of specialists and antiquarians, its extraordinary shelf life should suggest to us something of its value as a roadmap not only to the early decades of the new republic but to much of the nineteenth century.

Can early American books regain such a readership in the twenty-first century? Again the case of The Coquette is instructive. In the spring of 2004 the Peabody Historical Society (PHS), led by Martha Holden and Bill Power, aimed to revive interest in Whitman and in Foster’s novel among local residents. Along with calling for a town read, the society sponsored dramatic renderings of parts of the novel as well as some of Whitman’s extant poems; Peabody Veterans Memorial High School (PVMHS) added the book to the American literature curriculum; and the Peabody Historical Commission and Peabody Institute Library placed a new headstone at the gravesite—one modeled on the version that appeared in Foster’s novel. The new headstone even reproduces the conventions by which early printers sought to create the image of a headstone on the printed page. On its face, that is, the new headstone bears the outline of a headstone as it would have appeared in print, along with repeated winged-skull icons common to early American grave markers. The appearance of these print conventions on an actual “restored” headstone suggests, perhaps, the ways in which the “real” Elizabeth Whitman was eventually overshadowed by her fictional counterpart from Wharton’s novel. Outside the cemetery gates a sign now announces Whitman’s grave as a stop on the Massachusetts Literacy Trail. A few years after the new headstone arrived, and unrelated to the PHS celebration of Whitman, another local resident created a virtual gravesite for Whitman on the popular Website findagrave.com, where readers of Foster’s novel or those who simply stumble upon the story fresh can leave their thoughts along with virtual flowers (and tears) of their own.

The renewed attention given to Whitman and Foster beyond the university classroom suggests that early American books still have much to teach ordinary Americans, even about a world whose political luminaries, thanks to an unending parade of biographies and even HBO miniseries, now feel like familiar friends. During the Peabody discussions of The Coquette, as the PVMHS English department chair, Michalene Hague, wrote to me, “it became clear that people were learning about the era as it presented women’s roles and the lifestyles of ‘acceptable’ society; social mores then and now were discussed and regional connections explored. Our students, living as they do surrounded by history which they take for granted or often forget, benefitted in a community pride way—knowing that the early townspeople looked past the ‘sin’ and nurtured Elizabeth Whitman’s needs at the time.” Another local teacher and community historian, S. M. Smoller, who had brought Whitman’s story to local attention a few years earlier during a Women’s History Month celebration, was drawn to Whitman as a writer, not simply a literary heroine. “As I scrutinized her poetry,” Smoller recalls, “I was taken with her voice, especially when she adopts an attitude of anger and admonishes her deserting lover to go on and live although she knows her life is over.” Smoller was intrigued, too, by the story’s long popularity, the stuff of local legend. Salem resident Robert Buckley, who created the virtual gravesite for Whitman, has one theory: “I believe The Coquette fell into a category of novel that was long on titillation, and offered just enough moral instruction or consequence to justify the titillation. I think it was entertaining to readers because the story of a chaste, well-bred lady’s ruination packed an erotic wallop.”

Who reads an early American book? With a recommendation like that one, even you might.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.3 (April, 2009).

Bryan Waterman is associate professor of English and American literature at New York University and author of Republic of Intellect: The Friendly Club of New York City and the Making of American Literature. His essay “Elizabeth Whitman’s Disappearance and Her ‘Disappointment'” appears in the April 2009 issue of The William and Mary Quarterly.