Will the Real Henry “Box” Brown Please Stand Up?

For over two years now, I have been following the trail of a fugitive slave—but one who turned escape itself into an art form. On March 23, 1849, in Richmond, Virginia, an enslaved man named Henry Brown packed himself into a large postal box marked “Philadelphia, PA: This Side Up With Care” and mailed himself to freedom. Twenty-seven hours later, after periods of excruciating travel in which his box was turned upside down several times, he emerged unscathed. Sources report that he even sang a psalm of praise while promenading the yard, flush with victory. This was one of the most spectacular escapes of the antebellum period, and “Box” Brown rapidly became a famous antislavery orator, touring the United States and England with a moving panorama about slavery—large vertical spools painted with scenes of enslavement and freedom—called Henry Box Brown’s Mirror of Slavery. Brown’s escape was celebrated visually by way of several engraved broadsides featuring his song and box and a lithograph of his escape, all of which circulated from 1849-1850. Two narratives of his life were penned, and he continued to perform as a singer, actor, magician, and mesmerist (an early form of hypnotist) in England, the United States, and Canada well into the early 1890s.

Ever the escape artist, Brown sought to evade nineteenth-century culture’s prescriptions for appropriate African American behavior, as well as for the representation of Blacks within art. But was he successful?

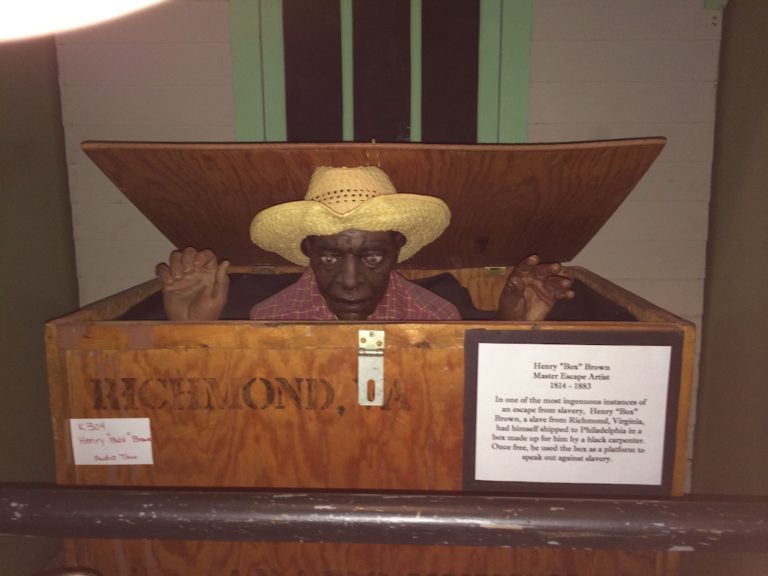

Brown’s remarkable tale has continued to grip the imagination of the general public. Recent portraits of his escape by box have been created by National Geographic, on television, in performance pieces, musicals, operas, books for children, graphic narratives, and even in a wax figure at Baltimore’s National Great Blacks in Wax Museum (fig. 1).

Yet scholarship has lagged behind this swell of public interest. To date there is only one scholarly book about Brown (by Jeffrey Ruggles) and it mainly concentrates on the years before 1875, when Brown returned to the United States with his wife, Jane, daughter, Annie, and son, Edward. To date, many basic factual details about this fascinating man are unknown, such as when he learned magic, whether he was literate, and even when he died. Behind the missing biographical information lies a deeper issue: scholars have not thoroughly excavated the complex multi-media performance work—defined here in terms of the combination of diverse media (visual, textual, aural, and oral)—that Brown fashioned throughout his life.

At some point about two years ago, it became my mission to try to complete the tale of Brown’s incredible life and art, and to figure out who the “real” Henry Box Brown was—the man behind the mask, the man who might exist apart from the many roles he would perform. I had already uncovered key details about Brown’s life. For example, my sources indicated that Brown learned conjure (African magic) from another enslaved man while he was still in slavery and wove it into all of the spectacles he created. Sources I uncovered also indicate that he was literate, writing and performing heroic roles in his own dramas while in England, and that he continued to perform as a mesmerist, musician, and lecturer during the last decade of his life, before he died and was buried at Toronto’s famous Necropolis Cemetery in 1897 (fig. 2).

After extensive research, I have come to the conclusion that Brown manipulated alter-egos throughout his life, including (but not limited to) such sobriquets as “The King of All Mesmerists,” “The African Chief,” and “Dr. Henry Brown, Professor of Electro-Biology.” He created a trickster-like presence and an ever-changing, innovative performance art that melded theater, street shows, magic, painting, singing, print culture, visual imagery, acting, mesmerism, and even medical treatments. Brown’s multi-media art attempted to move beyond the flat and stereotypical representation of African Americans present in the phenomenally popular transatlantic performance mode of the nineteenth-century minstrel show. Ever the escape artist, Brown sought to evade nineteenth-century culture’s prescriptions for appropriate African American behavior, as well as for the representation of Blacks within art. But was he successful? And could I ever uncover the “real” Henry Box Brown?

Act One: A Man and His Box

“I entered the world a slave. . . . Yes, they robbed me of myself before I could know the nature of their wicked arts,” comments Brown in the opening words of his second autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself (1851). In these lines, Brown configures enslavement as a type of negative sorcery (it is his owners, not Brown, who practice “wicked arts”). He is “branded . . . with the mark of bondage” and will only escape by rebranding himself as something more than “stolen property,” as something magical and perhaps even more than human.

Born in 1815 or 1816 on a plantation called Hermitage in Louisa County, Virginia, Brown’s enslavement was not harsh compared to what other slaves endured—he was never beaten or starved. But after his pregnant wife, Nancy, and the couple’s three children were sold away from him in an act of brutal robbery (Brown had been paying his wife’s master Cottrell money on the express condition that he not sell Nancy), Brown seems to have undergone some sort of radical transformation. Initially, in the 1850 narrative, he portrays himself as enduring a type of living death: “My agony was now complete, she with whom I had travelled the journey of life in chains, for the space of twelve years, and the dear little pledges God had given us I could see plainly must now be separated from me for ever, and I must continue, desolate and alone, to drag my chains through the world.” But Brown eventually emerges from this state into a desire to “snap in sunder those bonds by which I was held body and soul.” The image of a miraculous snapping of slavery’s shackles eventually would be incorporated into Brown’s stage shows, to great effect.

At some point in 1849, Brown decided to escape, and he claims that the idea of escaping by box came to him in a sort of magical or mystical moment: “One day, while I was at work, and my thoughts were eagerly feasting upon the idea of freedom, I felt my soul called out to heaven to breathe a prayer to Almighty God. I prayed fervently that he who seeth in secret and knew the inmost desires of my heart, would lend me his aid in bursting my fetters asunder, and in restoring me to the possession of those rights, of which men had robbed me; when the idea suddenly flashed across my mind of shutting myself up in a box, and getting myself conveyed as dry goods to a free state.” Brown subsequently used $83 he had saved from his work as a tobacconist to persuade James C. A. Smith, a free Black, and Samuel A. Smith, a sympathetic white shoemaker, to help him with his plan to ship himself by Adams Express to a free state. Brown was nailed into his box and mailed to the office of Passmore Williamson, a Quaker merchant and active abolitionist, and received by Williamson and other members of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee (a branch of the Underground Railroad). He carried only an awl to bore holes into the box as necessary, and some water. Brown had, however, apparently prepared himself for his exit from the box; should he arrive alive, he would make a grand entrance into the world of abolitionist performance. His first words upon release were, “How do you do, gentlemen?” He then sang a remodeled version of Psalm 40 from the Bible chosen specifically to celebrate his release and freedom, a psalm that begins, “I waited patiently for the LORD; and he inclined unto me, and heard my cry.” It is difficult to see how mailing one’s self in a box from slavery to freedom involves “waiting patiently for the Lord,” but here as elsewhere, Brown cagily manipulates his extraordinary activity so that it does not violate dominant notions of Christian decorum.

As is evident in the astonished expression of the face of the man on the right in an 1850 lithograph depicting the opening of the box (fig. 3), there is already something miraculous about Brown’s escape, something magical and mysterious.

Brown could easily have died in the box if it had been delayed or sent to the wrong location. He could have been gravely injured when the box was turned upside down, placing him on his head. Yet Brown emerged unscathed. Even at this early date, perhaps Brown envisioned the box as a mystical and transformative space—one that might grant him not only freedom but also a magical resurrection. Oral accounts collected by Jim Magus, who interviewed African American magicians who knew of Brown, suggest that Brown may have learned magic as a boy from another slave. According to Magus’s sources, the adult Brown performed sleights of hand such as picking up a nail, closing his hand over it, intoning an African phrase, and then opening his hand to reveal that the nail had turned into an acorn. If planted, he would say, such acorns would grow into nail trees. In keeping with this idea of Brown as a magician, the box he escaped in may have symbolized to him a type of magic trick in which he could disappear, only to appear again somewhere else, transformed into something new—a free man.

While no definitive account exists that proves that Brown learned magic before his escape, it is clear that he used the symbols of enslavement in later performance work and magic shows. For Brown, both slavery and freedom were entities to be conjured, then, and he drew on both subversively to create symbols for his performances of magic. For example, in shows in England he sometimes restaged his own boxing and unboxing, as Jeffrey Ruggles and others have shown. In another magic act he developed, he would have himself swaddled in Houdini-like fashion in a large canvas sack and shackles, from which he would miraculously escape. Perhaps most importantly, performance posters from the 1870s that have been preserved indicate that his magic act used a number of different boxes to make items appear and reappear: “The Programme will consist of the following: destroying and restoring a handkerchief . . . the wonderful Flying Card and Box Feat . . . the wonderful experiment of passing a watch through a number of Boxes” (emphasis added). The solid and singular space of the postal crate is transformed in his magic act into an entity that is open, plural, and miraculous. It is also possible that Brown employed, in his acts, something known as a Proteus Box, commonly used by magicians or their assistants at the time. These magic boxes had trap doors in the bottom, side, or back from which the magician escapes or seems to vanish, and then he or she might re-enter the box through this portal and seem to come back. Sometimes mirrors were placed diagonally to create a “safe zone” within the box so that it merely looked empty. These Proteus Boxes had to be carefully designed or some spectators, as the box was turned, might find that they were looking at themselves in these mirrors. If Brown utilized such a magic box in his act, the formerly enslaved individual would seem to dematerialize and rematerialize; a viewer also might see himself or herself momentarily and fleetingly in the sightlines of the magic box, certainly an unsettling situation. Perhaps, then, in Brown’s magic act, the box itself comes to symbolize not the living death of slavery but a plural and open space of miraculous transformation, of destruction and also resurrection.

Act Two: A Man and His Panorama

Brown may have learned magic during his enslavement, and threaded it through all of his performance work. Yet he also employed numerous other forms of art in his act, and many of these modes involved a type of early multimedia performance work involving music, paintings, narration, and street performance. For example, after his escape by box, Brown developed a panorama of the experience of enslavement that he showcased in both the United States (in 1850) and in England, where he had to move after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act and an attempt to recapture him. Brown’s panorama first opened in Boston on April 11, 1850, and was a huge success; according to Christine Ariella Crater, “large crowds gathered to view Brown’s Mirror, and newspapers applauded. The Boston Daily Evening Traveler named it ‘one of the finest panoramas now on exhibition.’” Brown’s panorama contained forty-nine scenes, probably eight to ten feet high, painted onto a canvas scroll; Josiah Wolcott (an ornamental sign-painter who had contributed to other abolitionist efforts) seems to have been the primary artist creating most of the images for it. The actual panels of the show have been lost, but various press descriptions of them are discussed by Jeffrey Ruggles and Daphne Brooks.

By all accounts, Brown was a dynamic performer, and his panorama itself incorporated a number of different performance modes. Especially after he began performing in England, it appears that Brown’s art became more sensational, as slavery became (for British audiences after the abolition of slavery in the U.K.) a site of particular excitement and voyeuristic fascination. The following incident reported in the Leeds Times (England) on May 17, 1851, indicates the ways in which Brown used the spectacle of his enslavement in a performative mode:

Great Attraction Caused in England by Mr. Henry Box Brown, a Fugitive Slave who made his escape from Richmond, in Virginia, packed up in a Box, 3 feet 1 inch long by 2 feet wide, and 2 feet 6 inches high. Mr. Brown will leave Bradford for Leeds on Thursday next, May 22nd, at Six o’clock, p.m., accompanied by a Band of Music, packed up in the identical Box, arriving in Leeds by half past Six, then forming a Procession through the principle streets to the Music Hall, Albion Street, where Mr. Brown will be released from the Box, before the audience, and then give the particulars of his Escape from Slavery, also the Song of his Escape. He will then show the GREAT PANORMA OF AMERICAN SLAVERY, which has been exhibited in this country to thousands.

This is no sedate recitation of events like that performed by antislavery orators such as William and Ellen Craft, who also toured in England after staging a spectacular escape from slavery in which Ellen (who was very light-skinned) passed as white and male and William (who was darker) passed as her enslaved property. There is a band, a parade, and a spectacular release; Brown then sings the song of his escape and the panorama of American slavery is shown. As the stage manager, Brown organizes and masterminds the show, but he also narrates and performs in it. In so doing, he expresses control and even ownership over his ordeal, turning his enslavement and escape into an exciting adventure rather than a tragedy that garners only pity or sympathy.

In England, Brown expanded his performance repertoire even further, shattering expected decorum for how former U.S. slaves should speak and act. For instance, he took on new identities such as “the African chief,” as this notice from the Preston Guardian on May 4, 1861, indicates: “Panorama of Slavery—the Panorama of Slavery exhibited by Mr. Henry Box Brown closed in Burnley on the evening of Wednesday first. During his stay, Mr. Brown, who is a man of colour, has attracted considerable attention. On several occasions he paraded the streets dressed as an African chief; and Mrs. Box Brown occasionally described her panorama of the Holy Land. Presents were also given away toward the close of his stay.” While other fugitives, such as Frederick Douglass, were emphasizing their Americanness, Brown creates an exotic lineage for himself, as well as a new stage character who (like Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko) may have had a noble origin. As Marcus Wood notes, through such shows, Brown “shattered the ceremonial and rhetorical proprieties of the formal lecture hall. He introduced elements of his own art and folk culture and fused them with the visual conventions of the circus, beast show, and pictorial panorama.” In so doing he broke away from other abolitionists, but he also challenged the notion of enslaved identity as flat or stereotypical, restaging and reenacting his miraculous demolition of the bonds of enslavement and bursting into new personae with each new performance.

Act Three: A Man and His Magic

Yet Brown was still, in a fashion, shackled by the bonds of enslavement, as he continued to climb into and out of the box in which he escaped, which he carried from place to place with him for many years. My suspicion is that Brown increasingly turned in the later part of his life to magic and mesmerism because these performative modes offered him a stronger means to symbolically take control of the traumatic legacy of slavery. On Jan. 12, 1867, the Cardiff Times reports that Brown was having great success in England with his lectures on the subjects of “Mesmerism and Electro Biology.” Brown may have used his magic and mesmerism to turn the white viewer himself or herself into a spectacle. In England, Brown worked with the mesmerist Chadwick, who possessed, one account said, “a most wonderful influence of all who submitted themselves to his operation: he sent them to sleep, awoke them, made them jump about transfixed to their chairs; at his command they were riveted to the platform, from which they could not move, unless commanded to do so by the operation; they jumped, they danced, they rang imaginary bells, rolled about, held one leg in the air, as long as the mesmerizer choose, and then they were all sent to sleep again.” As Ruggles suggests, because Brown had lived so many years as someone who had to “submit” to the authority of the masters, as well as the public, he might now relish using mesmerism to have absolute control over a white audience’s mental and physical powers.

When Brown returned to the United States in 1875 and then settled in Canada in the early 1880s with his wife and children (Edward and Annie), he continued to perform as a mesmerist and magician, crossing the border frequently. Shows by Brown are listed in the Salem Gazette in 1875 as well as in the Oct. 17, 1878, issue of the Bangor Daily Whig and Courier (Bangor, Maine). After this Brown apparently moved on to Canada, where the Markdale Standard of September 28, 1882, lists him performing “a dramatic entertainment” on October 10. The nature of the dramatic entertainment in Markdale is unclear, but what is clear is that Brown often multiplies the modes in which he performs, moving beyond mesmerism into what seems to be early forms of medical treatment. For example, we find him applying for, and being granted, a permit to perform in London, Ontario, in 1882. A newspaper describes the planned performance as follows:

Professor Box Brown appeared in the Town Hall last night, and obtained leave to address the Council. He related the thrilling scenes and incidents connected with his escape from slavery, and how he was packed away in a box three feet one inch in length by two feet in width; that he wanted the use of the hall for one of these lectures, and if so granted would expose conjuring, give an exhibition of legerdemain, and would lecture on animal magnetism, biology, sociology, tricology, and micology. The use of the hall was granted, the Professor to pay all expenses. (London Advertiser, November 16, 1882)

Brown relates his enslavement (again), but he also plans to lecture to his audience on a variety of scientific subjects including biology, sociology, tricology (presumably trichology, the study of hair loss), and micology (presumably mycology, a branch of science concerned with the healing and harmful properties of fungi). Brown here appears to become a type of healer or doctor.

Of all these roles, it appears that mesmerism and magic were closest to Brown’s heart. Indeed, he continued to perform as a mesmerist and magician in London, Ontario, for at least four more years. The London Advertiser reports on March 1, 1883, that “Prof. Box Brown applied for the use of the [City] Hall for a lecture on mesmerism, and a free ‘invite’ to the members of the Council, whom he would undertake to mesmerize individually or collectively. His application was favorably received.” Three years later, the Daily British Whig (another London, Ontario, newspaper) reports on April 30, 1886, that on May 1 “‘Box’ Brown is advertised to exhibit his feats of magic in the town hall.”

In these shows, Brown seeks to again turn slavery itself into a type of spectacle—but a spectacle that he can control and manipulate through magic acts and the proliferation of visual and sensory modes of performance. Ruggles contends that over the twenty-five years during which Brown performed in Britain, from 1850 to 1875, he appears to have “emancipated himself, in a sense, from his personal history of enslavement.” Yet rather than emancipating himself from the history of enslavement, perhaps by repeatedly employing the symbols of bondage (shackles, boxes, and so on), in acts of mesmerism, magic, and conjure, Brown attained a type of emotional dominion over these experiences and was able to reshape and refigure them for different performative purposes. Brown’s performances may have been a form of witnessing and testifying to the trauma that was enslavement, but one that allowed him to once again restage his story in a manner that gave him control over its ultimate outcome and meaning.

The modes Brown employed were not only visual; instead he attempted to call up a powerful multisensory experience of enslavement, one that might put the audience into the moment of slavery. When Brown first stepped out of his original box in 1849, singing was part of his performance and he apparently possessed an excellent voice; in later years he continued to incorporate music into his shows. The Northern Tribune (Cheboygan, Michigan) lists a performance on Dec. 1, 1883, “under the formidable name of Professor Box Brown’s Troubadour Jubilee Singers,” and the Weekly Expositor (Brockway Centre, Michigan) from Aug. 16, 1883, has a notice of a concert by Brown and the Jubilee Singers, as does the Daily British Whig (of London, Ontario) on May 4, 1886. At times Brown’s family also performed with him, as this notice in another Ontario newspaper—the Brantford Evening Telegram of Feb. 2, 1889—makes clear:

Last evening, Professor Brown and Family gave one of their unique entertainments in Wycliffe Hall (YMCA location) to a fair audience. First, Professor Brown told us about slavery and his escape from the slave scouts to Philadelphia in a box from which incident he was for many years called “Box Brown.” He then proceeded to give a number of feats of legerdemain (tricks of a stage magician) of the usual order and after which the Company rendered a number of planation songs which were well appreciated by those present. The ladies were very good singers and there was more of plantation energy than usual in such entertainment. The Professor stated at the close that a number of gentlemen in the city were anxious to have him give a lecture on slavery and to do so in about two weeks.

After the popularity of the acclaimed Fisk Jubilee singers in the 1870s and early 1880s, as Adrienne Shadd has documented, a number of African American and African Canadian groups like the Ball Family Jubilee Singers and the O’Banyoun Jubilee Singers performed in this mode, often singing slave songs and Negro spirituals. Brown and his family appear to have joined the rising tide of interest in jubilee singers and singing.

Of course, jubilee singing was not the only mode of popular art to utilize “plantation songs.” Minstrel shows also used this type of music, and they were commercial successes in this time period, both in the United States and Canada. These acts mocked and stereotyped African Americans and glorified slavery. Such a mode of performance is evident, for example, in the 1894 production at the Canadian National Exhibition titled “In Days of Slavery.” Archival posters for “In Days of Slavery” describe it as a “Grand Afro-American Production” that featured “fun, mirth and melody, introducing Cotton-Picking Scenes, Old-Fashioned Melodies, Southern Plantation Songs, Buck and Wing Dancing, Cake Walks, etc., by the world famous Eclipse Quartette.” Given that these types of shows were popular in this time period, the nature of the Brown family’s 1889 performance of “plantation songs” calls for further research. However, it is vital to note that in later shows, Brown continues to multiply performance modes to create an early form of multimedia art: orally, he narrates his escape; visually, he shows magic tricks, and aurally his family sings plantation songs. Brown’s art engages with slavery as he attempts to control it through the activation of multisensory aesthetic forms that might mediate and refigure its trauma.

Conclusion: Mysterious to the End

Further study of Brown is necessary, for we have only scratched the surface of this fascinating early African American/African Canadian performance artist’s work, especially in regards to his post-1875 years. Brown has much to teach us about representations of African Americans in nineteenth-century transatlantic visual culture. Brown played with, mocked, and hollowed out the symbols of enslavement, while crafting an artistic identity that was magical and transformative. He carved routes into and out of the metaphorical box in which the dominant culture attempted to contain him, frequently pushing back against the limiting way African Americans were configured in popular nineteenth-century performance modes such as the minstrel show.

However, Brown’s story is not yet concluded. Much remains to be discovered about the final decade of Brown’s life (1887-1897), and whether he was still performing in Toronto. Toronto Street Directories, legal documents from Toronto General Hospital, and the city of Toronto tax rolls from the 1880s and 1890s that I have consulted indicate that Brown lived in Toronto from 1886-1897, sometimes listing his employment as “Professor of Animal Magnetism,” “Lecturer,” or “Traveler.” Toronto death and cemetery records that I have uncovered indicate that Brown died on June 15, 1897, and is buried in Toronto’s Necropolis Cemetery. By the time of his death, tax rolls and census records show that both children had married and were living elsewhere. He unsuccessfully sued Toronto General Hospital (from whom he had been renting a property since 1886) in 1892-1893 after he fell through some stairs they refused to repair. As late as 1891, tax rolls for the city of Toronto list his occupation as “Concert Conductor.” Therefore it is possible he was still involved in music, but no actual performance notices have been found. A great mystery of Brown’s life remains, then. Did he ever escape the demand to perform enslaved subjectivity? To put this another way, did he ever symbolically stop climbing into and out of his original box?

Another enigma concerns the remaining members of Brown’s family who performed with him, and whether they carried on his artistic legacy in some fashion. Brown’s daughter, Annie, appeared with him in magic acts when she was five and (as we have seen) she sang with him in Brantford when she was nineteen. She paid for his funeral plot in Necropolis, but at the time of his death she was married and living in Pennsylvania. A singer and music teacher, she lived to be 101 and according to the Kane Republican (of Kane, Pennsylvania) died on April 13, 1971. Her daughter Gertrude Mae Jefferson also lists her occupation in a 1920 census record as being in the theater and music. After Brown’s death, his widow, Jane, lived with her daughter, Annie Jefferson, until June 6, 1924, when she too died (fig. 4).

Brown’s artistic heritage may have lived on in his wife, daughter, or granddaughter. But to date little is known of their work in music or theater, and that is another piece of the story of Box Brown that demands further archival research.

Perhaps we might envision Brown’s life as itself a sort of magic act. Every great magic trick has three parts. In the first part, called “the pledge,” the magician shows something ordinary, such as a deck of cards, a bird, or, in this case, a man. The magician asks you to inspect this ordinary man, this ordinary entity, and to make sure it is real, unadulterated, and “normal.” In the second part of the trick, called “the turn,” the magician takes this ordinary object and makes it do something extraordinary: disappear or perhaps fly away. In the third act of the trick (considered the hardest), called “the prestige,” the magician has to bring back the object that has magically disappeared. To some extent, Brown does this—we see him take an “ordinary man” (the slave Henry Brown) and make him disappear. He then brings him back, transformed through a series of alter-egos: “Box Brown,” “Professor Henry Brown,” “The African Chief,” and so on. But in a certain sense, I am not sure that Brown has in fact been brought back. His outlines remain murky, mysterious, and unstable. But perhaps that is all for the good. Brown ultimately provides a larger-than-life hero fit for our modern times—one who ceaselessly transforms himself in order to shape a realm of personal and artistic liberation, a realm of freedom in which he could never be entirely captured by any box, by any magic trick, or by any one performative space.

Acknowledgments

I owe a great debt to the following individuals for help with this essay: Jeffrey Ruggles, Heather Murray, Karolyn Smardz Frost, Jeannine DeLombard, Anna Mae Duane, Walter Woodward, Mary Chapman, Linda Cobon, Guylaine Petrin, Peter Linehan, Michael P. Lynch, Brendan Kane, and librarians at Toronto Public Library (especially Irena Lewycka). I also thank the Humanities Institute at the University of Connecticut, the Felberbaum Family Foundation, and the Office of the Vice President for Research at the University of Connecticut for financial support of research travel.

Further Reading

Basic details of Brown’s early life are contained in two autobiographical works: Narrative of Henry Box Brown, Who Escaped from Slavery, Enclosed in a Box 3 Feet Long and 2 Wide. Written from a Statement of Facts Made by Himself. With Remarks Upon the Remedy for Slavery. By Charles Stearns (Boston, 1849) and Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself (Manchester, 1851). For other details about the escape, see William Still, The Underground Rail Road: A Record (Philadelphia, 1872). The best scholarly treatment of Brown’s life and art is provided by Jeffrey Ruggles in The Unboxing of Henry Brown (Richmond, 2003). Astute analysis of Brown’s performance work can also be found in Daphne Brooks, Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850-1910 (North Carolina, 2006) and Marcus Wood, “‘All Right!’: The Narrative of Henry Box Brown as a Test Case for the Racial Prescription of Rhetoric and Semiotics” in American Antiquarian Society: A Journal of American History and Culture 107:1 (1998): 65-104. The reception of Brown’s work in Boston is discussed by Christine Ariella Crater in “Brown, Henry Box” (see the Pennsylvania Center for the Book, spring 2011). Treatments of Brown’s magic act or magic in this time period can be found in Jim Haskins and Kathleen Benson, Conjure Times (New York, 2001), in Jim Magus, Magical Heroes: The Lives and Legends of Great African American Magicians (Georgia, 1995), in David Price, Magic: A Pictorial History of Conjurers in the Theater (New York, 1985), and in Jim Steinmeyer, Hiding the Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible and Learned to Disappear (New York, 2003). On Black jubilee singers in Canada, see Adrienne Shadd, The Journey from Tollgate to Parkway: African Canadians in Hamilton (Toronto, 2010).

Accounts of performances discussed in this article include: the Leeds Times (England) on May 17, 1851, and the Preston Guardian on May 4, 1861 (both available through 19th Century British Library Newspapers Online 1600-1950, Gale/Cengage); the Cardiff Times on Jan. 12, 1867 (available through Welsh Newspapers Online); the Salem Gazette in 1875 (see Artemis, Gale Group); the Bangor Daily Whig and Courier (Bangor, Maine) on Oct. 17, 1878 (see British Newspapers Online 1600-1950, Gale/Cengage); the Markdale Standard on Sept. 28, 1882 (available from Ontario Community Newspapers, OurOntario.ca); the Northern Tribune (Cheboygan, Michigan) on Dec. 1, 1883, and the Weekly Expositor (Brockway Centre, Michigan) on Aug. 16, 1883 (both available from Chronicling America, a Library of Congress website); the London Advertiser on Nov. 16, 1882, and March 1, 1883, and the Daily British Whig (London, Ontario) on April 30, 1886, and May 4, 1886 (both available from the digital archive Paper of Record); and the Brantford Evening Telegram on Feb. 2, 1889 (account reproduced in the Brant Historical Society Newsletter 4:4 [Winter 1997]: 4-5).

This article originally appeared in issue 16.1 (Fall, 2015).

Martha J. Cutter is a professor of English and Africana Studies at the University of Connecticut, where she teaches classes on African American literature. She has published widely on nineteenth-century African American literature and culture and on visual/verbal texts.