Bills for “ferryages” appear to be listings of overseers or the enslaved coming to the College on business. Conversely, the records suggest that faculty members rarely visited the Nottoway Quarter. A document from 1742 notes two enslaved individuals, “runaway from Nottoway,” arrived in Williamsburg with a complaint to the faculty about conditions on the plantation. President James Blair and the College Masters appointed Thomas Dawson and John Graeme to “Visit the Plantan:, to enquire into the Matters of Fact, and to endeavour [sic] to put things to rights.” No further information was recorded concerning a resolution of this matter. It appears faculty oversight of the Nottoway Quarter was minimal. The only instance of a Nottoway manager being ordered to make a report on the state of affairs at the Quarter was in 1768. Aside from the 1742 occurrence, no other eighteenth-century documents have been found referencing Nottoway Quarter runaways or those who were reported as absent without leave and nor were any runaway ads posted in The Virginia Gazette. However, one Bursar record from 1765 notes the payment of a charge of thirteen shillings and four pence to the Nottoway Plantation “For takng up a runaway.” It is unclear whether this amount was directed at compensating Nottoway residents for tracking a locally escaped slave or expenses associated with recovering a Quarter laborer.

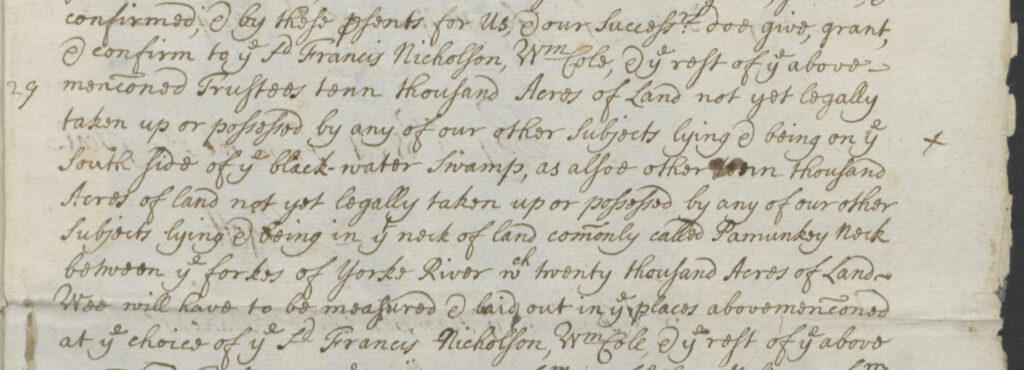

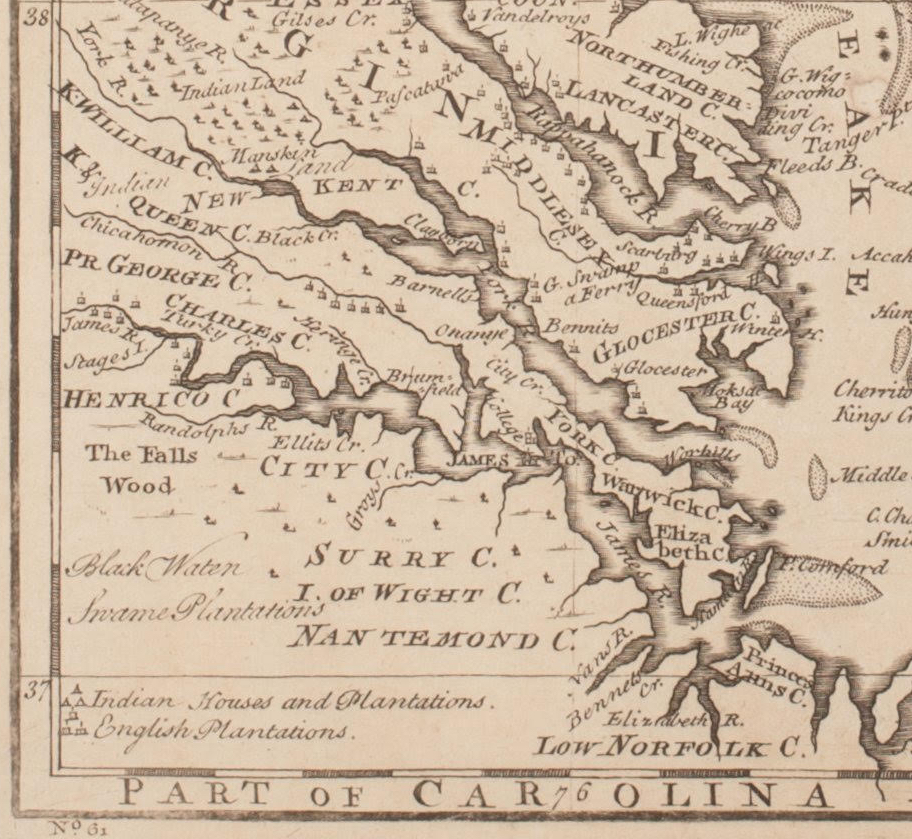

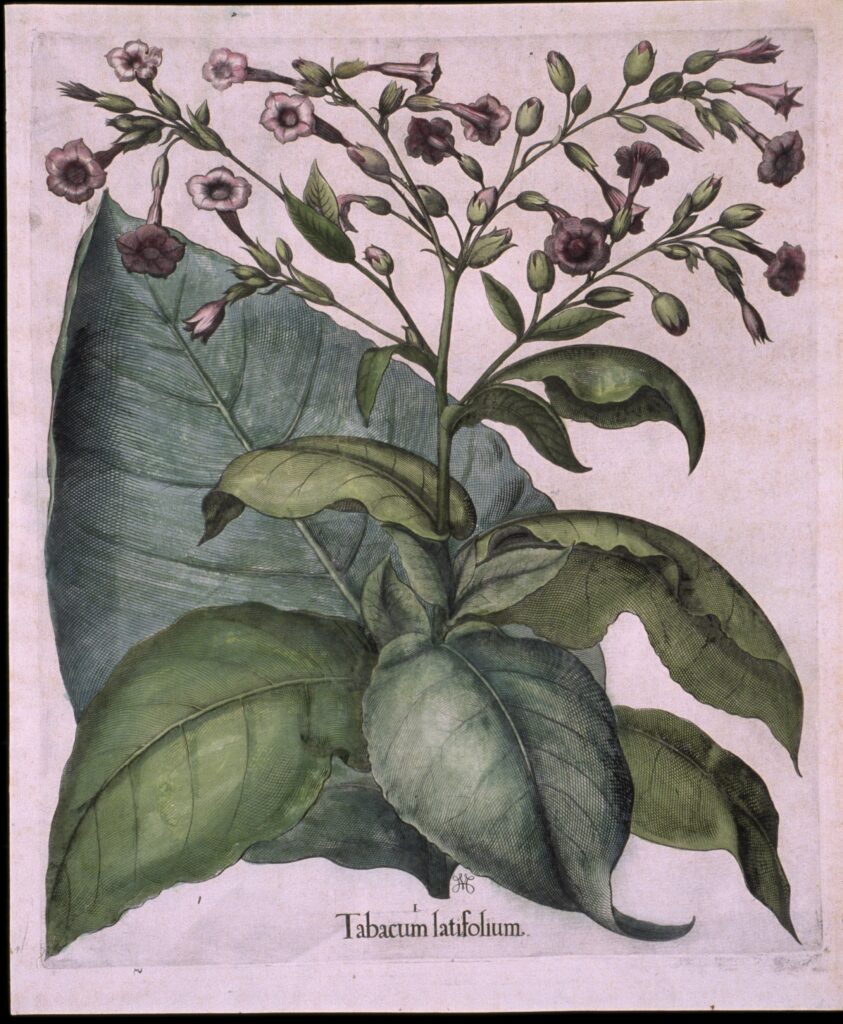

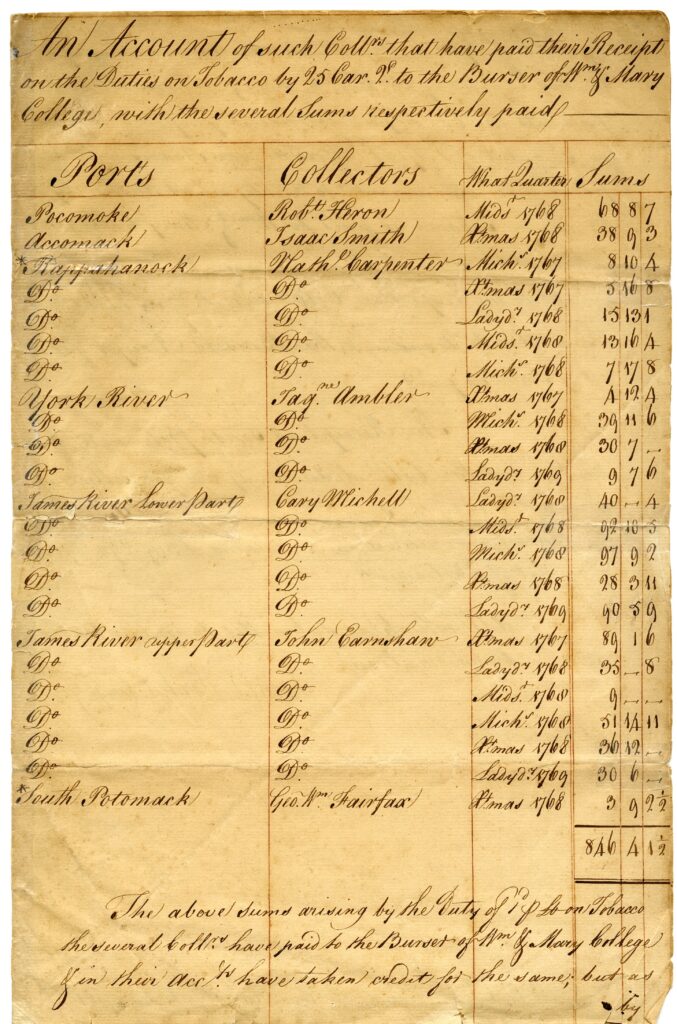

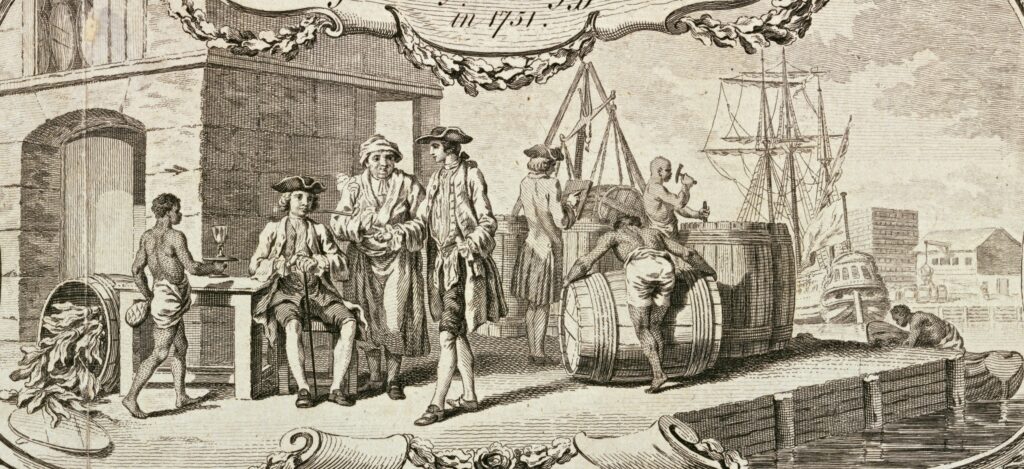

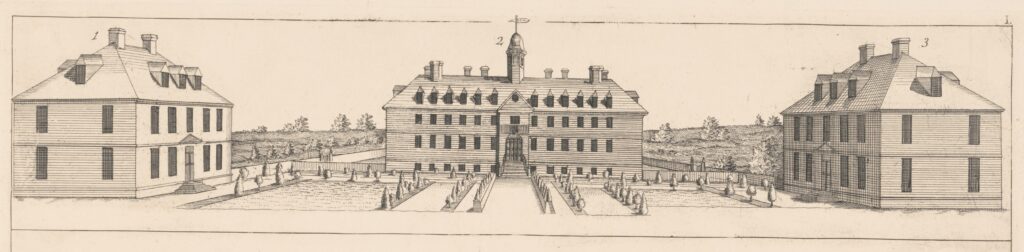

The Nottoway Quarter was thus firmly situated within, and a product of, settler colonialist ideology. Returning to the extant documents—the bursars’ ledgers, faculty minute books, and College papers—allowed us to look more deeply into these processes. While the documents of William & Mary are not obscure, by using the lens of political economy to evaluate the College’s historical finances, new details emerged about the institution’s reliance on expropriated Native treaty lands and enslaved agricultural labor. The dispossession of Native lands for the purposes of organizing English tobacco plantations was a deepening and broadening of merchant capitalism in Virginia. Colonial taxation of tobacco grown by forced labor on colonized Indian lands, conjoined with quitrents derived from treaty lands transferred from the Crown’s trust to the College were added to yields from William & Mary tobacco sales in London. In nearly all instances, College tobacco was grown and harvested by enslaved peoples. Examining the positionality of the Nottoway Quarter to the early financial support of the fledgling College of William and Mary makes clear the deeply intertwined social relations of slavery, political economy, and settler colonialism. Presently, The Lemon Project: A Journey of Reconciliation and the Bray School Initiative are efforts underway at William & Mary to study and respond to the College’s troubling history as it relates to slavery and its legacies. A new consideration of the interconnectedness between the Charter’s call to educate “the Western Indians” and the phrase extolling efforts for the “maintenance and support of the College in all time coming” also requires an acknowledgment of that troubling history and a response to Indigenous communities.

Further Reading:

Gregory Ablavsky, “Making Indians White: The Judicial Abolition of Native Slavery in Revolutionary Virginia and Its Racial Legacy,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 159 (no. 5, 2011): 1457-531.

C.S. Everette, “‘They shalbe slaves for their lives’: Indian Slavery in Colonial Virginia,” in Indian Slavery in Colonial America, ed. Alan Gallay (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009).

Alan Gallay, The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670–1717 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003).

Susan H. Godson et al., The College of William & Mary: A History, vol. 1: 1693–1888 (Williamsburg, VA: King and Queen Press, 1993).

The Lemon Project, William & Mary.

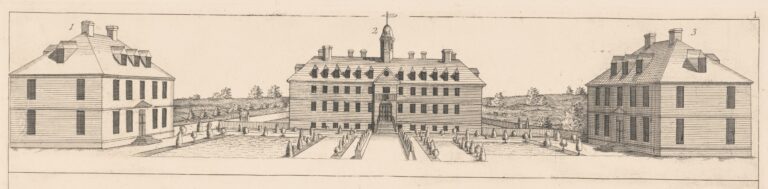

Danielle Moretti-Langholtz and Buck Woodard, eds., Building the Brafferton: The Founding, Funding and Legacy of America’s Indian School (Williamsburg: The Muscarelle Museum of Art, 2019).

E. Morpurgo, Their Majesties’ Royall Colledge: William and Mary in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Washington, D.C.: Hennage Creative Printers, 1976).

Jennifer Oast, Institutional Slavery: Slaveholding Churches, Schools, Colleges, and Businesses in Virginia, 1680–1860 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Kristalyn Shefveland, Anglo-Native Virginia: Trade, Conversion, and Indian Slavery in the Old Dominion, 1646–1722 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018).

Buck Woodard, “Indian Land Sales and Allotment in Antebellum Virginia: Trustees, Tribal Agency, and the Nottoway Reservation,” American Nineteenth Century History 17 (no. 2, 2016): 161-80.

This article originally appeared in December 2022.

Buck Woodard is a Professorial Lecturer of Anthropology at American University in Washington, D.C. and chair of the Virginia Indian Advisory Board’s Workgroup on State Recognition for the Secretary of the Commonwealth. Recent work includes “An Alternative to Red Power: Political Alliance as Tribal Activism in Virginia” (2020) and as co-author of Building the Brafferton: The Founding, Funding, and Legacy of America’s Indian School (2019).

Danielle Moretti-Langholtz is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Anthropology at William & Mary in Williamsburg. She is also the Director of the American Indian Resource Center and the Director of the Native Studies minor. As well, she is the Curator of Native American Art at the Muscarelle Museum of Art and the co-author of Building the Brafferton: The Founding, Funding, and Legacy of America’s Indian School (2019).