Witnessing Historical Thinking: Teaching Students to Construct Historical Narratives

The advent of narrative history in the popular press makes engaging history students seem like a simple task. However, as teachers we are up against myriad competitors that shape our students’ historical sense. From the History Channel, to MythBusters, to Disney’s Pocahontas, students come to class with preconceived notions of what should constitute engaging approaches to history. And for most, analytic articles on Puritan theology or Native American animism will not do. Sam Wineburg, a Stanford professor of education and observer of history teachers, reminds us, “historical thinking, in its deepest forms, is neither a natural process nor something that springs automatically from psychological development. Its achievement … actually goes against the grain of how we ordinarily think. … The odds of achieving mature historical understanding are stacked against us in a world in which Disney and MTV call the shots.” Coaching students to develop these critical and analytical thinking skills is one facet of my teaching. Another is to engage my students’ imaginations.

John Demos, emeritus professor of history at Yale, eloquently describes the importance of imagination: “Clio is a time traveler, and we, her acolytes, delight in following her on long and varied journeys of the mind. Words, pried loose from documents, carry us across the centuries. Our experience is as full and rewarding as our imagination allows it to be. And in these travels imagination is all.” In my teaching, I find that narratives consistently awaken students’ imaginations, enticing them to make the history they are expected to learn their own.

Yet “narrative history” is frequently discussed in opposition to “critical history” or “analytic history,” the argument apparently being that narratives are somehow not suitable to the crafting of complex historical arguments. The core of teaching history at the secondary level, for many of us, is to teach students to read critically and write analytically—that is, to analyze texts and then make arguments about them. The focus is typically not on engaging students in the creation of narratives. The well-worn analogy between the historian and the detective remains popular today—indeed, the PBS show History Detectives perfectly encapsulates the connection, one that is repeated in countless lessons online and in print that lead students to identify and marshal evidence in order to support a thesis. As Peter Stearns asserts, history involves “An ability to form an argument, using data for a purpose, a capacity to glean data from primary sources…[and refine] some capacity for handling diverse interpretations and testing theories about change.” Giving students a framework that lets them see the information they gather as evidence being collected in support of an argument helps them learn the larger skill of thinking analytically about data.

The historians’ tasks of textual analysis and critical analytic writing can be taught in a variety of ways. I have found that, contrary to the opposition within the discipline between narrative and critical history, using narrative to teach these skills helps students connect the habits of thinking like a historian to their own lives, and actively engages them in the content I want them to learn. Wineburg writes, “[h]istory teaches us a way to make choices, to balance opinions, to tell stories, and to become uneasy—when necessary—about the stories we tell.”

This essay reflects themes and ideas presented by Darcy R. Fryer in “Common School” (Common-Place, Volume 12, Number 2). Teaching Early America, as she presents it, provides numerous possibilities to incorporate new scholarship into the secondary school classroom. Here I will share a number of lessons and assignments that I have used successfully to guide students to explore primary and secondary texts. The work engages students’ historical imaginations and builds analytical and critical thinking skills—in short, these lessons teach students how to use historical narrative to make an argument.

I have been teaching early American history for more than twenty years. My primary assignment is to teach the first half of a two-year American history course. We focus on American history from the beginnings (Kennewick Man) through 1877, the end of Reconstruction. Our core text for the fall is Alan Taylor’s American Colonies, which challenges students to see early America through the trifocal lens of environmental history, ethnographic study, and the interconnected networks of the Atlantic world. By explicitly teaching content through a range of media and having students see each medium as a potential model for historical interpretation, students are prepared to craft their own interpretations of history by using narrative.

To understand the clash of cultures in the encounter between Europeans and Native Americans, we watch Bruce Beresford’s film version of Brian Moore’s historical novel, Black Robe. The film is rich, clear, and engaging (although somewhat problematic in its portrayal of the Iroquois). Students analyze how the film’s narrative makes an analytical point about history. For example, in the film’s depiction of an Algonquin band delivering Father LaForgue (based loosely on the Jesuit missionary Noel Chabanel) to a Huron village, cultural misunderstandings ensnare both the Natives and the French. When LaForgue demonstrates the power of writing, some see it as sorcery—the capturing of the spirit. LaForgue encourages this Native interpretation because it imbues him with the special wisdom he believes himself to possess as a Christian, in the process making an argument about the nature of relations between Europeans and Native peoples. We discuss the film, and they read excerpts from The Jesuit Relations. Because the film models for them how to consider historical events through contesting lenses, they are able to write coherently (in an analytic essay assignment) about the clash of cultures.

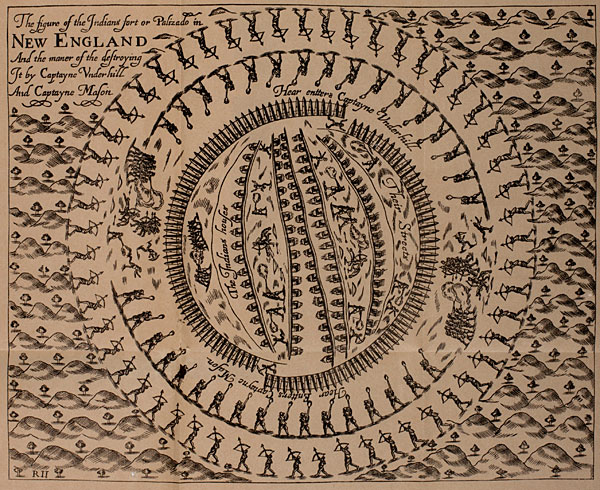

We also analyze an English woodcut depicting the Pequot War. Like Black Robe, this image requires students to reflect on perspective. Most of my students come to class with simplistic notions about Natives in this period, viewing them as disorganized but loosely allied against the Europeans, noble savages facing a technologically and bureaucratically superior adversary. The more careful observers in my classes notice that the image shows English troops, led by captains Underhill and Mason, attacking a Pequot walled village, aided by members of at least one Native tribe (who they learn included the Narragansett, keen rivals of the Pequot for access to wampum). The woodcut tells a dramatic and violent story of the unstable alliances that shaped seventeenth-century British North America, but it also constitutes a visual narrative that very quickly makes an analytic point about a history my students usually think they know.

To help students become more conscious of the complexity of historical events, I have created a lesson called “Fateful Years: Seventeenth Century Crisis in North America.” In it, students are asked to develop their own narratives in order to better understand the notion of historical patterns. Their charge is to gather primary and secondary sources, and use them to tell the story of conflicting perspectives on the causes of the Pueblo Revolt, Bacon’s Rebellion, or King Philip’s War —all of which occurred within seven years of each other, but in vastly different parts of the North American continent, involving different players, and driven by entirely different causal forces. Students read their sources, determine key historical actors, actions, and chronologies. Then they dramatize the conflict in a simulation or “play” of sorts. They are assessed on their understanding of the different points of view and the coherence of their narratives, both in the simulation (and script) as well as in a reflection essay. Students remember this lesson, and genuinely enjoy it. In fact, they advocate for more student-crafted simulations as the year progresses.

The major research project for the fall semester is designed to encourage students to pull together all these new skills of historical thinking (point of view, continuity, change, chronology) and incorporate them in creating a piece of analytical history. Using the annual theme and framework of National History Day, students choose topics, generate “reporter” and “essential” questions, and take notes in a shared “Google doc” so that I am able to monitor their progress and give constructive feedback. National History Day (a bit of a misnomer) is a structured series of presentations where students share their work before judges and the public. I am not so much interested in the competition that History Day engenders, but in the process of creating a project. My students often use local archives, museums, and sophisticated online archives to find primary sources, and read current scholarship on their topic. For example, students in recent years have used materials in the Massachusetts Historical Society to create projects on the Essex Junto, Cotton Mather, and John Adams. Students have used the American Antiquarian Society for research on Noah Webster and John B. Gough and the temperance movement. One student traveled to Sheffield, Massachusetts, to interview scholars about Mum Bet (Elizabeth Freeman) and the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. Another went to the Portland Historical Society in Maine to find a treasure trove of documents on the Maine Law of 1851. Together with current scholarship from JSTOR and books from interlibrary exchanges, my students are able to do real historical work, and they are excited to put those skills to use. Here is one example.

One student recently became interested in the story of the alliances between the Narragansett and the Puritans in the seventeenth century. As he read accounts of the Narragansett, he found himself asking questions about the causes of the destruction of the tribe in the so-called “Great Swamp Massacre” of December 1675. He knew he needed to do more than simply provide a narrative of the events. Eventually, he crafted a thesis about the diplomatic and racial (ethnic) causes of the massacre, and tied it to a long-term pattern of Native removal. For his project, he then wrote a script (using free storyboarding software called Celtx) and started filming. He travelled to South Kingston, Rhode Island, and trekked out into the woods to the actual site to get some shots, but the principal body of his film was a narrative driven by document analysis. To gild the lily, he wrote original music for the film and played it on his violin and guitar as the soundtrack. His film, “The Great Swamp Massacre,” was 10 minutes long and a remarkable demonstration of his ability to think historically and present a complex view of a historical event. His film was shown at the Omohundro Institute for Early American History and Culture conference in Boston that year—quite an achievement for a high school student!

Demos notes that “[i]t is … strangely jarring for us to see or touch some pieces—some physical chunk—of the panorama of the past. Confronted with artifacts (instead of verbal description), imagination goes limp, sensation intervenes…The effect [of artifacts] was immediate, and visceral, and acute anxiety. So here is the way it looked and was: no mere words could quite have conveyed the feeling.” My students grapple with that distance and try to make sense of it for themselves.

Stéphane Lévesque argues that the goal of history teaching is to “devise a conception of history and identify procedural concepts of the discipline relevant to twenty-first-century students, to give students the means to a more critical and disciplinary study of the past,” and to encourage students toward “disciplinary history” rather than “memory-history.” But the divide between discipline and memory, between argument and narrative, need not be so absolute. By providing different models of historical inquiry, guiding students as they analyze primary and secondary sources toward a specific project, and then coaching students as they research and craft their own historical narratives (in films or websites, for example), we can help students use narrative to discover the power of historical thinking.

Further Reading

The best books to start to understand “historical thinking” are Samuel Wineburg’s Historical Thinking and other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Temple, 2001) and Stéphane Lévesque’s Thinking Historically: Educating Students for the Twenty-First Century (Toronto, 2008). Also see the website Historical Thinking Matters (historicalthinkingmatters.org), Peter Stearns, “Thinking Historically in the Classroom” (Perspectives, October 1995), and the collection edited by Donald A. Yerxa, Recent Themes in Historical Thinking: Historians in Conversation (South Carolina, 2008). The core fall text for my class is Alan Taylor’s American Colonies: The Settling of North America (Penguin, 2002), although I have recently considered using Daniel K. Richter’s Before the Revolution: America’s Ancient Pasts (Cambridge, 2011), but have yet to switch. The Native image referred to in the article is “The Figure of the Indian Fort or Palizado in New England” (London, 1638). For more information on National History Day, see the analysis by Scott Scheuerell in The History Teacher 40:3, and their website (www.nhd.org).

This article originally appeared in issue 12.3 (April, 2012).

Charles L. Newhall is a history teacher at St. John’s Preparatory School in Danvers, Massachusetts, and co-editor of the Common School column. His research focuses on the intellectual and cultural history of the early national republic.