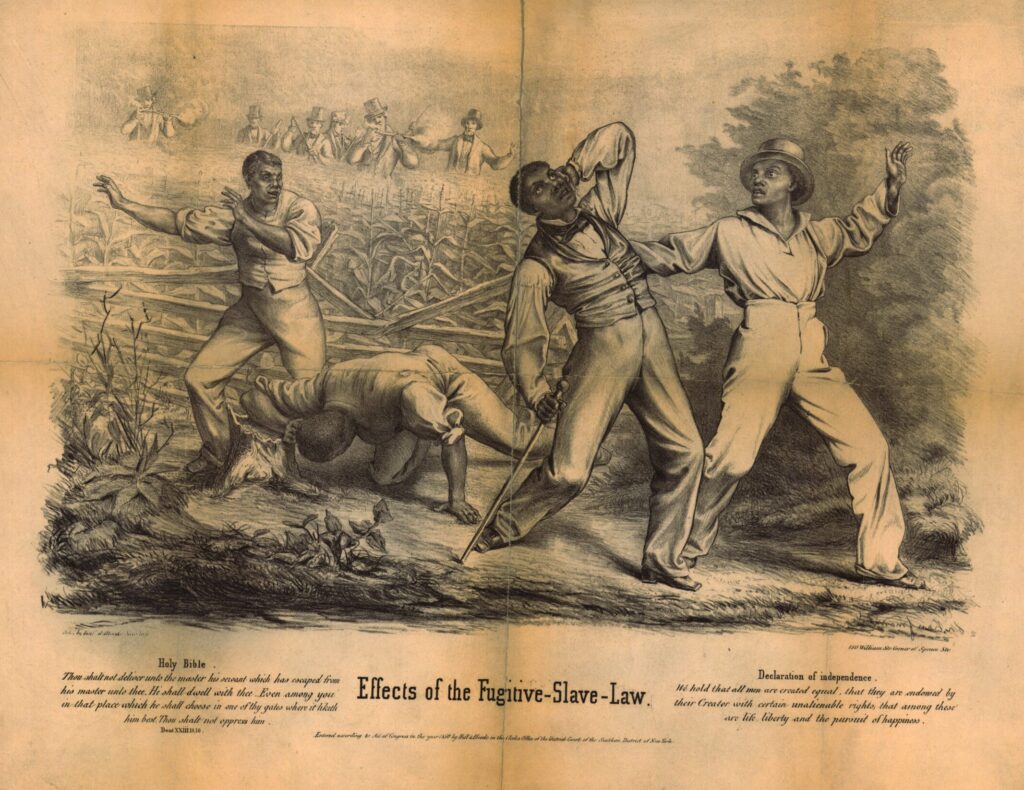

In crafting a “road to the Civil War” narrative, Carter Jackson could do more to acknowledge the deeper origins of the abolition movement and to the dynamic, revolutionary discourse with which Black abolitionists were in conversation. While it makes sense to bookend a story about the abolitionist tactical shift from moral suasion to violence with the 1830s and the 1860s, that story leaves out antislavery and Black radical thought before Walker and Garrison and suggests that the political discourse of violence sprung up in their wake. Carter Jackson’s analysis would have benefited from a brief comparison of early and later abolitionism and how Black thought explored and superseded the Revolution’s ambivalent promise of freedom and equality.

With Force and Freedom, Carter Jackson makes a stimulating and insightful debut which will have a major influence on abolition movement scholarship. She recenters Black leadership in the movement and illuminates how critical it is to understanding the shift in strategy from public persuasion to political violence. While Carter Jackson could have paid more attention in her analysis to the gendering of Black abolitionism and to the earlier movement and development of abolitionist thought, she compellingly connects Black abolitionism and the embrace of revolutionary ideas. Black people and their resistance to slavery were indeed crucial to the expansion of American freedom and equality during the antebellum period and the Civil War. They led a movement devoted to securing perhaps the most radical and elusive principle of all American history: Black humanity.

Further Reading

Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, 2nd ed. (1967; Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992).

Christopher Cameron, To Plead Our Own Cause: African Americans in Massachusetts and the Making of the Antislavery Movement (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2014).

François Furstenberg, “Beyond Freedom and Slavery: Autonomy, Virtue, and Resistance in Early American Political Discourse,” Journal of American History 89, no. 4 (Mar. 2003): 1295-330.

Richard S. Newman, The Transformation of American Abolitionism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

Paul J. Polgar, Standard-Bearers of Equality: America’s First Abolition Movement (Williamsburg and Chapel Hill: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (1961; Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

Benjamin Quarles, “The Revolutionary War as a Black Declaration of Independence,” in Slavery and Freedom in the Age of the American Revolution, ed. Ira Berlin and Ronald Hoffman, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 283-301.

Manisha Sinha, “Coming of Age: The Historiography of Black Abolitionism,” in Prophets of Protest: Reconsidering the History of American Abolitionism, ed. Timothy Patrick McCarthy and John Stauffer (New York: New Press, 2006).

Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

Manisha Sinha, “To ‘Cast Just Obliquy’ on Oppressors: Black Radicalism in the Age of Revolution,” William and Mary Quarterly 64, no. 1 (Jan. 2007): 149-60.

This article originally appeared in December 2023.

William Morgan is a Ph.D. student in the Indiana University Bloomington Department of History. He studies the cultural history of early America with emphases on early Black politics, the long Revolution, and the first abolition movement.