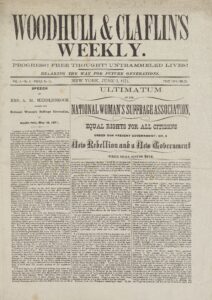

In the fall of 1870, famed feminist Victoria Woodhull published a scathing satirical work of utopian fiction that offered a daring dream—a socialist, agriculturally-based future where women had equal rights. The author of the utopian short story was Annie Denton Cridge. Today, Cridge lacks the fame of her contemporaries, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton or Susan B. Anthony, but for decades she labored on behalf of the nation’s most radical reform movements. Cridge was also an author of utopian fiction at a time when the genre was not as popular as it would become years later. Her utopian short story, “Man’s Rights; or, How Would You Like It?,” originally published in Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, was an amalgamation of the radical causes Annie supported. It combined her socialist and feminist dreams with a commitment to healthy living. The story is representative of a radical and alternative American intellectual current that Annie fostered for decades.

A Healthy Paradise: Annie Denton Cridge’s Feminist Utopia

Cridge’s American utopia did not singularly hinge on technological innovation or economic equality. It was a comprehensive achievement that combined political and economic equality with women’s autonomy and health.

Annie Cridge, born Annie Denton in England in 1825, emigrated to the United States with her brother, William Denton in the 1840s. In America, Annie met her husband, Alfred Cridge. The couple were political firebrands driven by a desire to remake the world into an equal, healthy, and socialist paradise. In the 1850s, Annie and Alfred put their zealous reform spirits to good use by editing a reform periodical, called The Vanguard, with Annie’s brother in Dayton, Ohio. The Vanguard was a spiritualist periodical with a socialist tint. The Cridges filled the pages of the paper with articles about socialist communities, gender equality, and spiritualism.

Annie and Alfred cautiously embraced the new religion for most of the 1850s. However, by 1857 their faith in spiritualism was resolute. Annie’s conversion occurred in 1857 following the death of her child, Denton. When Denton passed away, Annie claimed that she witnessed his spirit leave his body. She also claimed to be a psychometrist, a person capable of not only communicating with departed spirits but of seeing the past historical life of an object by touching it.

The Cridges’ interest in spiritualism was not surprising considering the support the movement gave to the women’s rights movement. Spiritualism recognized the equality of the sexes and carved out a space for women’s leadership within the religion. In her 1989 book Radical Spirits, historian Ann Braude demonstrated the intimate relationship between women’s rights and spiritualism and even the extensive participation of spiritualists in the abolitionist as well as health and dress reform movements. The Cridges were part of this radical circle that championed some of America’s most remarkable causes.

Annie’s spiritualism and self-proclaimed psychometry were not her only unconventional features. Annie and her husband were both committed socialists and vegetarians who envisioned a world colonized by hygienic communes. The two were inspired by the Associationists of the 1840s and 1850s, America’s most popular nineteenth-century communal movement.

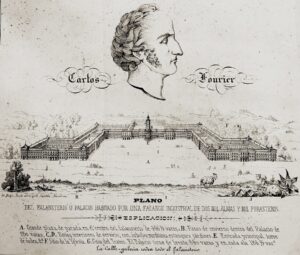

Associationism was a utopian-socialist campaign inspired by the writings of French philosopher Charles Fourier. Fourier’s American followers believed they could remake the world into a utopian paradise by creating a series of joint-stock communities called phalanxes. Associationism was one of the many utopian-socialist campaigns that flowered in the antebellum period. However, unlike other utopian movements such as the Shakers or the Oneida community, Associationism was not grounded in religious belief or headed by a charismatic leader. It followed Charles Fourier’s radical philosophy which admonished industrial development, criticized the anarchy of the capitalist economy, and rebuked repressive gender and sexual norms that perpetuated women’s oppression. Most importantly, Fourier posited a theory of psychological development where complete liberation relied on the fulfillment of individual passion.

In Fourier’s phalanx, diversity, democracy, and difference were obligatory. Societal harmony relied on balancing various passions and embracing political, class, and personality differences. This embrace of difference attracted a cadre of reformers to the movement, including abolitionists, women’s rights advocates, peace reformers, vegetarians, and socialists. From the 1840s to 1860s, Associationists founded dozens of phalanxes around the nation, including the popular Brook Farm community outside of Boston.

Of course, in practice, not all phalanxes were the same. Alfred Cridge, for one, had a clear, though not universally shared, vision of a phalanx that combined Fourier’s commune with vegetarianism and water-cure. He never succeeded in establishing the phalanx, but the Cridges sustained their utopian dream through The Vanguard, where they created “connection spaces” and wrote columns on “Reform Communities” to help readers join established communes and unite with other community-minded friends.

Even after The Vanguard ceased publication, Annie and Alfred contributed pieces on the benefits of clean and communal living to reform periodicals in the 1860s and 1870s. Eventually, they found a home at Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly where Alfred penned a series of columns on Fourier’s utopian-socialism and Annie published her most famous work of fiction—Man’s Rights.

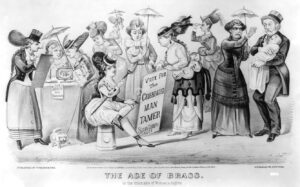

Man’s Rights was an impressive work of satire and utopian fiction that combined her various reform interests into a single utopian vision. In the story, Annie retells a series of dreams she experienced about a city in a faraway land. In these dreams, she visited a sublime city on the planet Mars where contemporary gender roles were reversed. In every house and every kitchen, Cridge encountered overworked and restless men responsible for the housework, cooking, and childrearing. The men were disenfranchised and lacked equal political and economic rights. While women served as the heads of households, the family’s breadwinners, and occupied all positions of government, men occupied the private sphere of the home.

When the city’s gentlemen housekeepers left their residence, Cridge observed that they were dressed in the most fantastic outfits. Many were dressed in ruffles from collar to pantleg and others wore delicate lace headdresses decorated with glitter and tinsel. As she walked past them, she listened to their conversations. They gossiped about fashion and romances. Cridge cringed at their degraded position.

For several more nights, Cridge returned to the city where she witnessed its men gradually protest their unequal condition. One night, Cridge attended a rally where the men of Mars demanded “men’s rights” and objected to the system of housekeeping that women forced them into. Eventually, the men’s rights reformers achieved partial success when their city adopted a system of collective housekeeping.

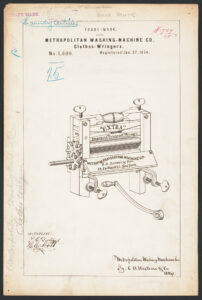

This system included large-scale kitchens with autonomous meal-making technology, caravan machines used to deliver meals to every household, and new washing and ironing machines. As opposed to an isolated domestic system where each individual man labored in the home, collective housekeeping saved time and money. It also freed men of the arduous domestic drudgery that their lives previously revolved around.

Significantly, an important appeal of the Associationist movement was its emphasis on the benefits of collective housekeeping for American women. Associationists emphasized the value and importance of domestic work but argued that housekeeping was forced upon women and used to restrict their social and economic freedoms. In an Associationist phalanx, residents cooked, cleaned, and laundered collectively to avoid waste and save resources.

Members of the phalanx performed labor according to their individual interests and their natural enthusiasm toward specific types of work. Fourier understood that some work was less desirable than others. To make up for this imbalance, laborers who performed unseemly work, such as cleaning, earned higher dividends than their fellow utopians. However, Fourier was not the Elon Musk of the eighteenth century. He largely eschewed technology and was suspicious of its role in liberation. He viewed the dirty and dangerous factories of the eighteenth century as detrimental to one’s mental and physical health and did not believe individuals could find joy in factory work. Fourier even imagined that most of the work performed in the phalanx would be agricultural, not industrial. He embraced collective housekeeping and large-scale communal laundries and kitchens because it emancipated women from the seclusion of the private sphere and provided more choice and freedom for individuals to pursue their vocational interests. His “labor-saving” technology did not provide more leisure time for the utopian. It merely saved the worker from unappealing work. Clearly this aspect of Associationism influenced Cridge as she made it an important part of her fictional vision of male emancipation on Mars.

Although the utopia of Annie’s dreams existed on another planet, her eighth dream transported her to a more familiar place: New York City ten years in the future. Within ten years, America elected its first woman president, half of the Senate were women, and prostitutes were no longer arrested and punished for participating in sex work. Instead, their male companions were arrested and placed in reformation houses.

When she returned to this new progressive New York in her last dream, she could not find any women in the city. The factories, workshops, businesses, schools, and hospitals were filled with men, but few women could be found. It was only after Cridge came upon a festival celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the women’s agricultural fair that she realized where America’s women had gone.

Fifty years earlier, the city struggled with a large population of impoverished women with little land, few opportunities, and no support. To remedy their circumstances, a large class of widows, wives, and single women moved out of the city to a vast space of uncultivated land. There, they started their own farms and made agriculture women’s work. Over the years, the grain, fruit, and vegetable farms they cultivated became their source of happiness and health. When Cridge awakened from her final dream, she hopefully asked “may not this dream, after all, be a prophecy?”

In Cridge’s story, America’s women embarked on an agricultural quest to achieve happiness, health, and control over their futures. Even after they achieved political and economic equality, laboring in unsafe and unhealthful factories harmed their physical and spiritual well-being. Cridge’s American utopia did not singularly hinge on technological innovation or economic equality. It was a comprehensive achievement that combined political and economic equality with women’s autonomy and health.

In 1870, Cridge acted upon her agricultural dream and left the East Coast for an agricultural colony in Riverside, California, where she remained until her death in 1873. Like many other vegetarian socialists, Cridge believed women’s emancipation and healthy living for all humans required a large-scale reorganization of societal relations. A sanitary agricultural farm where families and individuals could live cooperatively and grow fruits, vegetables, and grain was a means to achieve a better world. In this regard, Man’s Rights was an individual prophecy for Cridge. Unwilling to wait for the day when the utopia of her dreams finally appeared, she took matters into her own hands and spent the last years of her life attempting to make her work of fiction a reality. In an obituary published by Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, her husband Alfred wrote that “believing that occupation on the land was the keystone of woman’s independence,” his wife spent the last of her lifeforce sustaining the colony.

Read: Annie Denton Cridge, Man’s Rights; or, How Would You Like It? Comprising Dreams (Boston: William Denton, 1870).

Annie was not the only woman who published powerful works of utopian fiction in the mid-to-late 1800s. Decades before Charlotte Perkins Gillman published her popular work of utopian fiction, Herland, in 1915, utopian authors Marie Howland, Jane Sophia Appleton, Elizabeth T. Corbett, and Zebina Forbush published their own visions of a more equal, healthier, and perfect future on earth. Marie Howland, like Cridge, was also a utopian-socialist who participated in the Associationist movement and lived in several communes throughout her life. Cridge and her fellow utopian authors were part of a vibrant community of women authors who used their literary prowess and access to periodicals such as Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, and Godey’s Lady’s Book.

Cridge’s short story, not to mention her illustrious reform career, represents a more radical but influential side of mid-nineteenth-century politics. Existing alongside America’s more traditional reformers who advocated single-issue causes such suffrage and abolition, and the moral and bureaucratic reformers who looked to clean up America’s cities and political system, a cadre of radical socialists worked to reorganize America’s social and economic institutions and remake society into a second Eden. From the 1860s to the 1880s, Americans founded multiple utopian-socialist communities that highlighted the importance of a vegetarian diet and clean living such as Hygieana, Cedar Vale, the Lord’s Farm, Societas Fraternia, Joyful, Israelites, and various Brotherhood of Light and Theosophist communities. Cridge was a pioneer within this group of reformers who, from the 1840s to the 1870s, persisted in their efforts to remake the world, starting with the United States, into a happier and healthier utopia.

Further Reading:

Ann Braude, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001).

Carl Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative: Fourierism in Nineteenth-Century America (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1991).

Justyna Galant, “Ruptures in Separate Spheres: Deconstruction of Cross-Gender Solidarity in George Noyes Miller’s The Strike of a Sex and Annie Denton Cridge’s Man’s Rights,” Utopian Studies 29 (no. 2, 2018): 176–196.

Alfred Denton Cridge, Utopia; or, The History of an Extinct Planet (Oakland, Cal.: Winchester & Pew, 1970).

This article originally appeared in June 2022.

Ashley Garcia is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. She researches the history of utopian socialism in the United States and her dissertation examines the Associationist movement of the 1800s.