History happens on the internet, and so does historiography. In recent years, scholars and lay commentators alike have advocated an alternative vocabulary for describing the historical violence of racial slavery. We should substitute “enslavement” for “slavery”; “enslaved person” for “slave”; “enslaver” for “slave owner” or “slaveholder”; “slave labor camp” for “plantation”; “freedom-seeking” or “self-emancipated” for “fugitive.” These arguments have been advanced by public history and educational organizations, governmental agencies, and scholarly organizations—all aiming to address (and perhaps redress) the legacies of Atlantic slavery by centering questions of language. From this perspective, the oft-cited “power” or “importance” of language resides precisely in its capacity to inflict or alleviate harm. But this all-too-neat categorization of right and wrong, good and bad terms and phrases actually underestimates the power of language by insisting upon its moral and semantic stability. Language is far too dynamic and slippery a medium to serve as foundation for such broad normative claims. This move to revise our collective historical vocabulary, moreover, introduces as many complications as it seeks to resolve. In what follows, then, I aim merely to question the assumptions that undergird arguments for what I call reparative semantics and, in so doing, illuminate some of the historiographical problems that arise in the process.

First, we should endeavor to understand the arguments for reparative semantics on their own terms. The preference for “enslaved person” over “slave,” for example, is most often framed as a question of humanity or personhood. The phrase “enslaved person,” that is, supposedly acknowledges or restores the full humanity of the enslaved, whereas the term “slave” is objectifying, commodifying, or dehumanizing. “Slave” evacuates the personhood of historical subjects, signifying instead a totalizing identity altogether outside the realm of the human. In this sense, the phrase “enslaved person” is meant to stake a quasi-metaphysical claim: Those who were enslaved were not merely “slaves,” they were fully complex persons victimized by the institution of slavery. “Enslaved person” recognizes the complete humanity of the enslaved by detaching it from slave status. (It is worth noting that similar developments are taking place with respect to non-English languages. In Spanish, for example, esclavo might be replaced by esclavizado; in Portuguese, escravo by escravizado. Some speakers of French, meanwhile, have adopted the neologism esclavasigé.)

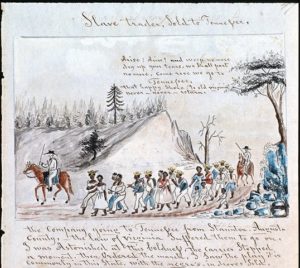

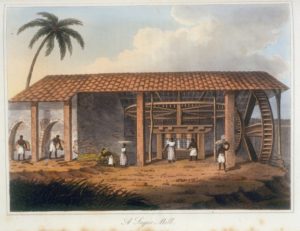

The preference for “enslaver” over “slave owner” or “slaveholder” works in similar ways. The former intends to emphasize the violent practices and processes that constituted racial slavery while deemphasizing the seeming neutrality of identity markers like “owner” or “master.” The latter terms, that is, function as little more than historiographical euphemisms obscuring the mundane forms of brutality to which the enslaved were subjected. This focus on historical process likewise bolsters the argument for using “enslavement” in the place of “slavery”—where one highlights how individual historical actors promulgated racial slavery and its attendant ideologies, the other suggests a kind of transhistorical phenomenon that operates of its own accord. Phrases like “freedom-seeking” or “self-emancipated” individuals, moreover, stress the agency of the enslaved where “fugitive” assumes the perspective of slaveholding legal regimes. Finally, the use of “slave labor camp” aims to supplant “plantation,” tinged as it is by a certain nostalgia for the “moonlight and magnolias” paternalism of the Old South.

As we can see, these are perfectly legitimate reasons to abandon one terminology for another. Still, I think the above arguments should give us pause. This is not to take issue with the use of terms like “enslavement,” “enslaved person,” or “enslaver”—all of which I use periodically in my own scholarship—but rather to question the normative argument that this language produces a more rigorous, righteous, or politically efficacious approach to the historiography of slavery.

Let’s consider the phrase “enslaved person.” First, there is the issue of the presumed equation of “slave” with an “identity.” I would be surprised if any scholar or student of slavery considered “identity” an appropriate term to describe what was in fact a legal status and social condition. Proponents of reparative semantics advocate a turn away from the term “slave” as a marker of identity, though it remains unclear whether anyone has made such an assertion in the first place. Second, suggesting that those enslaved in the African diaspora were not in fact “slaves” easily slips into a kind of social constructivism whereby “slavery” did not happen at all. That is, the argument goes, it is impossible truly to make any person a “slave” because their essential humanity cannot be extinguished: People are not “slaves,” they can only be “enslaved.” (This rhetoric seems especially risky at a time when myths of Irish or white “slavery” persist online and new conspiracy theories spread unabated—for example, that the Middle Passage never occurred because people of African descent are indigenous to North America.) Removing “slave” from our historical terminology implies that slavery is ultimately a state of being rather than a matter of law or social practice. In other words, “slave” is an ontological condition rather than the outcome of observable social and legal processes by which persons come to assume or inherit the status of “slave.” One could certainly make the former claim, but it would not be a historical one. Arguing that people cannot be “slaves” renders ever more difficult the task of understanding how that history itself unfolded.

Second, this claim arguably leads us to misunderstand the history of slavery as a process of reducing persons to nonpersons. As I have shown elsewhere, it is commonplace to describe slavery as the “commodification” or “dehumanization” of enslaved people. We often take for granted, for example, that slaves were nonpersons in the eyes of the law—or, as Saidiya Hartman has notably argued, that slaves’ legal personhood was only legible as criminality. This particular framing is troublesome on two fronts. First, it neglects a rich body of scholarship on the comparative law of slavery, which has demonstrated how distinct legal regimes in African, Iberian, Francophone, Dutch, and Anglo-American contexts, respectively, constructed and perpetuated enslavement as an institution and practice. If we know, for example, that Iberian and Dutch legal regimes—which shared a common ancestor in Roman canon law—endowed slaves with certain rights and obligations unavailable in Anglo-American contexts, then to insist that the slave is definitionally a legal nonperson is to privilege the latter over the former. This perspective thereby reifies a nationalist framework belying the truly global character of Atlantic slavery. Taking #VastEarlyAmerica seriously as an interpretive framework requires shirking the tendency to subsume diverse colonial histories to an Anglo-American model. And second, even if we limited our analysis to the United States or broader Anglo-American sphere, crucial work by historians including Laura Edwards, Ariela Gross, Martha Jones, Dylan Penningroth, and Kimberly Welch, among others, has revealed a deep history of American slaves’ legal claims-making in spite of their alleged lack of “legal personality.”

While rhetorically appealing, I would venture that this manner of conceptualizing history fundamentally misconstrues the historical dynamics of enslavement: Rather than seeking to extinguish the humanity of its victims, slavery rather invests in, and relies upon, their human capacity for suffering. As scholars across history and literary studies—including Walter Johnson, Christopher Freeburg, Jeannine DeLombard, and myself—have argued, we might yet frame our approach to the history of slavery not as the restoration of personhood to the enslaved, but as the recognition that enslaved personhood was the very basis of that system. (Indeed, recent philosophical and social scientific work suggests that similar forms of historical violence are predicated upon the humanity of its victims, not the deprivation thereof.)