About midway through my undergraduate seminar on American captivity narratives last fall, we were discussing one of the earliest American literary works to deploy this essential historic genre: Susanna Haswell Rowson’s 1794 play Slaves in Algiers, or, A Struggle for Freedom, a comedy-melodrama focusing on a group of Americans held captive in Algiers, one of the Barbary States of North Africa. The play is not distinguished by great literary excellence or readability, but it is fascinating in its complex mix of political agendas. On the surface level, the play was part of a wide public effort in the early 1790s to stir sympathy for the real white captives of the time. But it is equally dedicated to serving the ongoing commitment of Rowson (best known as the author of the wildly popular seduction novel Charlotte Temple) to advocate for women’s rights in the new republic and maintain the importance of female virtue. On other political levels, Slaves in Algiers reveals uncomfortable strains of xenophobia and anti-Semitism and–most conspicuously to readers in the present political era–it makes evident the deep roots of America’s imperial fantasies concerning the Islamic world.

The galvanizing moment in our class discussion came as we reread the play’s conclusion. Its closing words are shared by the young American hero and heroine, Henry and Olivia, separated by their respective captivities and now reunited following the Americans’ victory over their Muslim captors. Henry speaks of returning to the United States, “where liberty has established her court–where the warlike Eagle extends his glittering pinions in the sunshine of prosperity.” And Olivia concludes, “Long, long may that prosperity continue–may Freedom spread her benign influence thro’ every nation, till the bright Eagle, united with the dove and the olive branch, waves high, the acknowledged standard of the world.” “Hang on,” I told my students, “Now listen to this–” and I read to them from the conclusion of President Bush’s 2003 State of the Union speech: “America is a strong nation and honorable in the use of our strength. We exercise power without conquest, and we sacrifice for the liberty of strangers. Americans are a free people, who know that freedom is the right of every person and the future of every nation.” Gratifyingly, I heard sucked-in breaths and exclamations at the echoes between early national and contemporary political rhetoric as we contemplated the continuing presence of the past. Bush’s speech was delivered less than two months before the tanks rolled into Iraq; Rowson’s dialogue, less than a decade before the United States’ invasion of Tripoli, the first war authorized under the U.S. Constitution and the country’s first military victory following the Revolution. What my students and I shook our heads over was how precisely for both Rowson’s characters and the current administration the dream is the same: that the world will become an empire of liberty under the leadership of the United States, a country that considers itself entitled to tell everyone else what freedom means and impose itself as “the standard of the world.”

In both the early republic and the present, this troubling dream is recurrently enmeshed with stories of American captives abroad. Reading Slaves in Algiers was not the first time in the captivity class we had had occasion to consider recent events in Iraq. From the opening day, a touch-point for our discussions was the story of the captivity and rescue of Jessica Lynch, taken captive in an ambush in Nasiriyah in March 2003 (two major versions of the narrative, the TV movie Saving Jessica Lynch and the book by journalist Rick Bragg, I Am a Soldier, Too: The Jessica Lynch Story, appeared during the course of the semester). The intense public fascination with Lynch’s captivity and rescue and the less-than-subtle spin the events received in the hands of the military and the media made it abundantly clear that, though we might dwell in class on texts written in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the genre cannot be consigned to a dry past full of impossible religious beliefs and short on alternative narrative thrills.

Recognition of the historic resonance of the Jessica Lynch story came early. In an op-ed piece in The New York Times on April 6, 2003, less than a week after the rescue, Melani McAlister, a professor of American studies at George Washington University, characterized the heavily mythologized version of the story that initially circulated as “the latest iteration of a classic American war fantasy: the captivity narrative.” McAlister brought up parallels between Lynch and the first, most famous captive in the American tradition, Mary Rowlandson, held by Algonquian Indians during King Philip’s War in 1676. “For more than two centuries,” McAlister explained, “our culture has made the liberation of captives into a trope for American righteousness.” This analysis is absolutely right. However, literary works such as Rowson’s play and the nonfictional (or purportedly nonfictional) narratives that became popular in America beginning in the 1790s remind us that, along with the better-known Indian captivity narratives, there is a second captivity tradition focused on white slavery in the Barbary States. These stories encouraged early Americans to see themselves not just as members of a community under God, as Rowlandson’s narrative emphasizes, but as part of a nation finding its way in a complex international scene.

The story of Jessica Lynch’s nine days of confinement in the land of Saddam Hussein dovetails with the explicitly political concerns of the Barbary captivity tradition. Beyond offering the earliest American portraits of the Islamic world, captivity narratives and other writings about Barbary from the early republic contrast America as a land of liberty (“the greatest blessing human beings ever possessed,” wrote John Foss) with the tyrannies of Muslim rulers, a new set of oppressive masters to fill in for the British rulers the Revolution had dislodged. In his 1798 narrative, for example, Foss wrote that the Algerines’ “tenderest mercies towards the Christian captives, are the most extreme cruelties,” and quoted the Dey of Algiers, who declared, “[N]ow that I have got you, you Christian dogs, you shall eat stones.” Obviously, such polarizing accounts are politically expedient to this day. Yet at times, early accounts of Barbary provoked a challenge as well: stories of the horrors of white slavery (a term that from the outset writers used interchangeably along with “captivity” and “imprisonment”) could become an unsettling mirror for the nation, one that forced Americans to confront their own hypocrisy by recognizing the similar or worse slavery they practiced at home. In 1790, Ben Franklin made the point through a satiric hoax entitled “On the Slave Trade,” which exposed readers to the fallacies of a proslavery argument as spoken by an imaginary Algerine advocate of Christian slavery. In 1799, William Eaton put it much more bluntly: “Barbary is hell–So, alas, is all America south of Pennsylvania.”

At present we are discovering, I think, the continuing power of “Muslim captivity” to effect such disquieting moral reversals. Only a year and a half after the fact, the rescue of Jessica Lynch has begun to seem like a quaint memory, as our attention has been turned from American captives to American captors, from Lynch’s blond ingenuousness to the scary hard eyes of Lynndie England and her comrades at Abu Ghraib. What of “power without conquest” now? The linking of captivity with a vision of “American righteousness” has never seemed more fraught.

And, of course, in all of these events there is the question of gender. Captives or captors, the ones we remember most are the women. If the fate of Jessica Lynch, her friend Lori Piestewa (killed in the Nasiriyah attack), and Shoshanna Johnson (another captive who survived) spurred little overt discussion of their status as women or the issue of female soldiers, the behavior of Lynndie England and the other women cavorting in the photographs from Abu Ghraib have, at least for some, provoked not just a moral but a gender crisis. Barbara Ehrenreich has written, “A certain kind of feminism, or perhaps I should say a certain kind of feminist naiveté, died in Abu Ghraib.” What died, of course, is the idea that women would never do such things. The photos from the prison, Ehrenreich points out, display “everything that the Islamic fundamentalists believe characterizes Western culture, all nicely arranged in one hideous image: imperial arrogance, sexual depravity . . . and gender equality.” Gender equality: the very principle Susanna Rowson sought to promote through a tale of strong women confronting the Islamic world. Perhaps Slaves in Algiers can offer us as many insights as any modern commentary into the tangle of captivity, domination, and American self-definition that we are confronting, and what gender might have to do with it all.

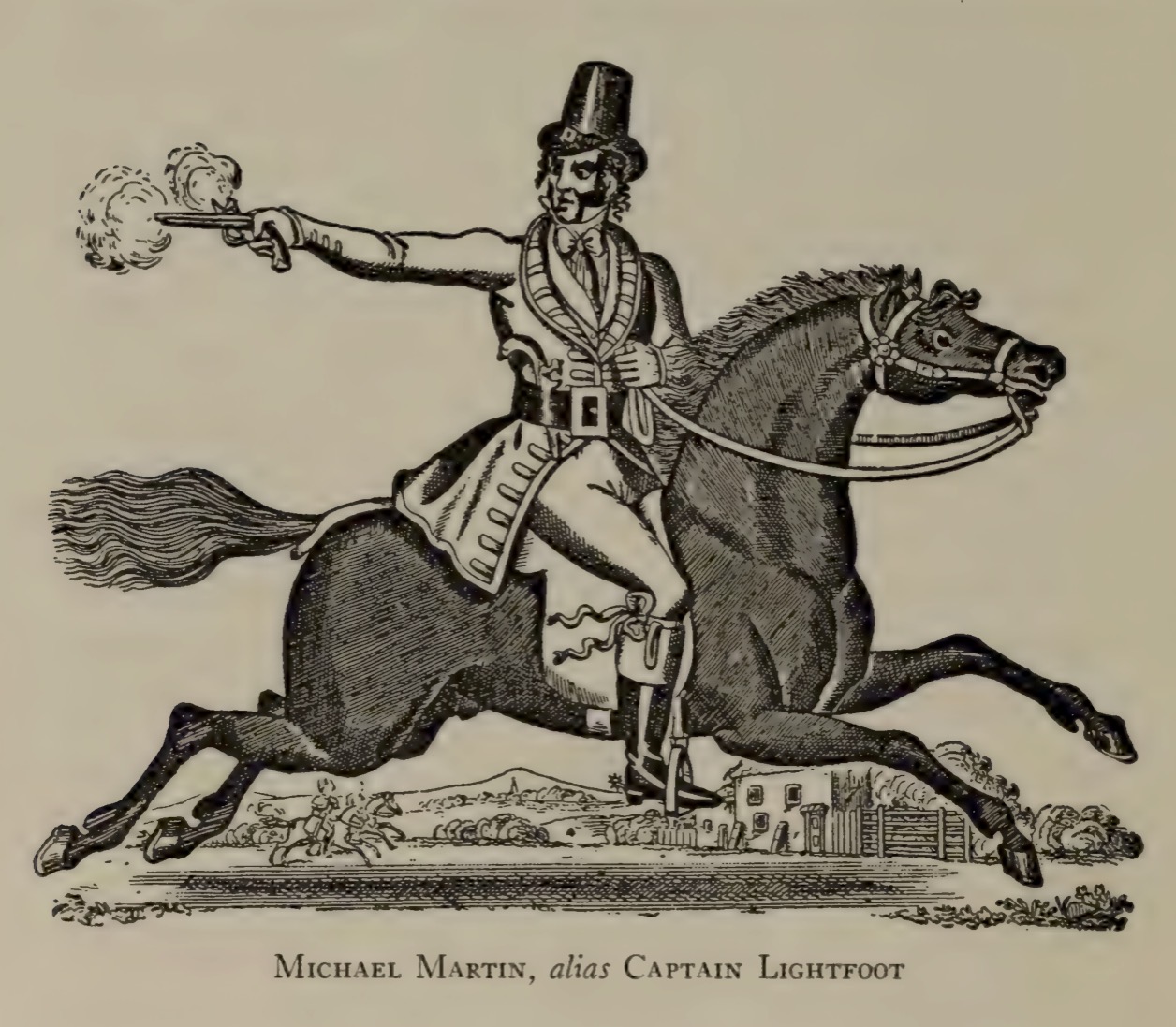

The origins of Barbary captivity reach back to 1492, when the Moriscos (or “Moors”) were violently expelled from Catholic Spain, culminating centuries of crusading violence between the two religions. This expulsion generated intense hostility among Muslims toward Spain and other Christian countries. The Barbary States of Algiers, Tripoli, Tunis, and Morocco–where the Moriscos settled after being driven from their homes–began an extensive program of privateering designed to attack European shipping and take slaves. While this practice had economic benefits and political advantages, vengeance remained a central motive; the pirates’ raids have been memorably characterized as a “sea-borne jihad.” There is no way of telling how many Europeans were enslaved, but the historian Robert Davis estimates that roughly thirty-five thousand Christians were held captive at any given time in the century following 1580, a figure startlingly high in comparison to the number of whites taken captive by North American Indians, if insignificant in comparison to the number of Africans and their descendants later enslaved in America.

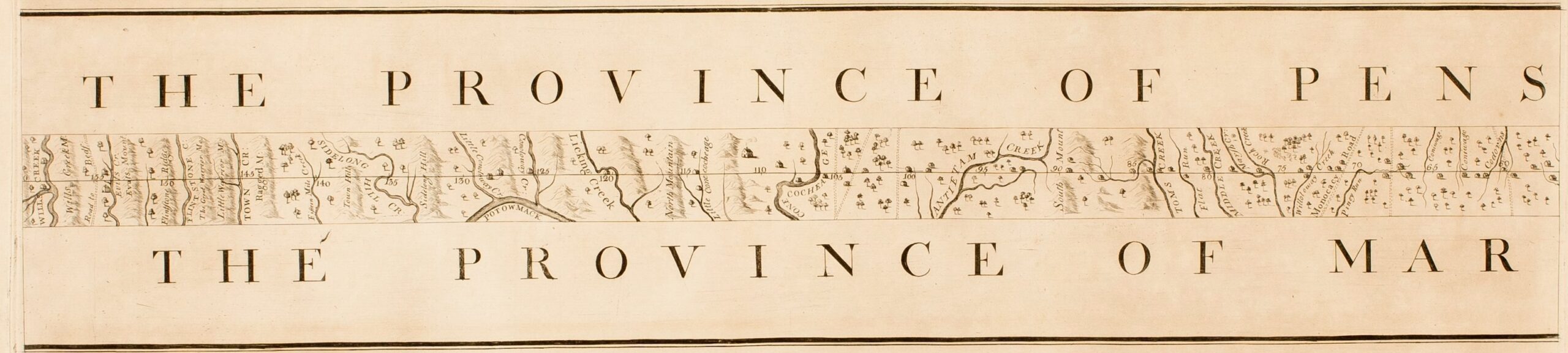

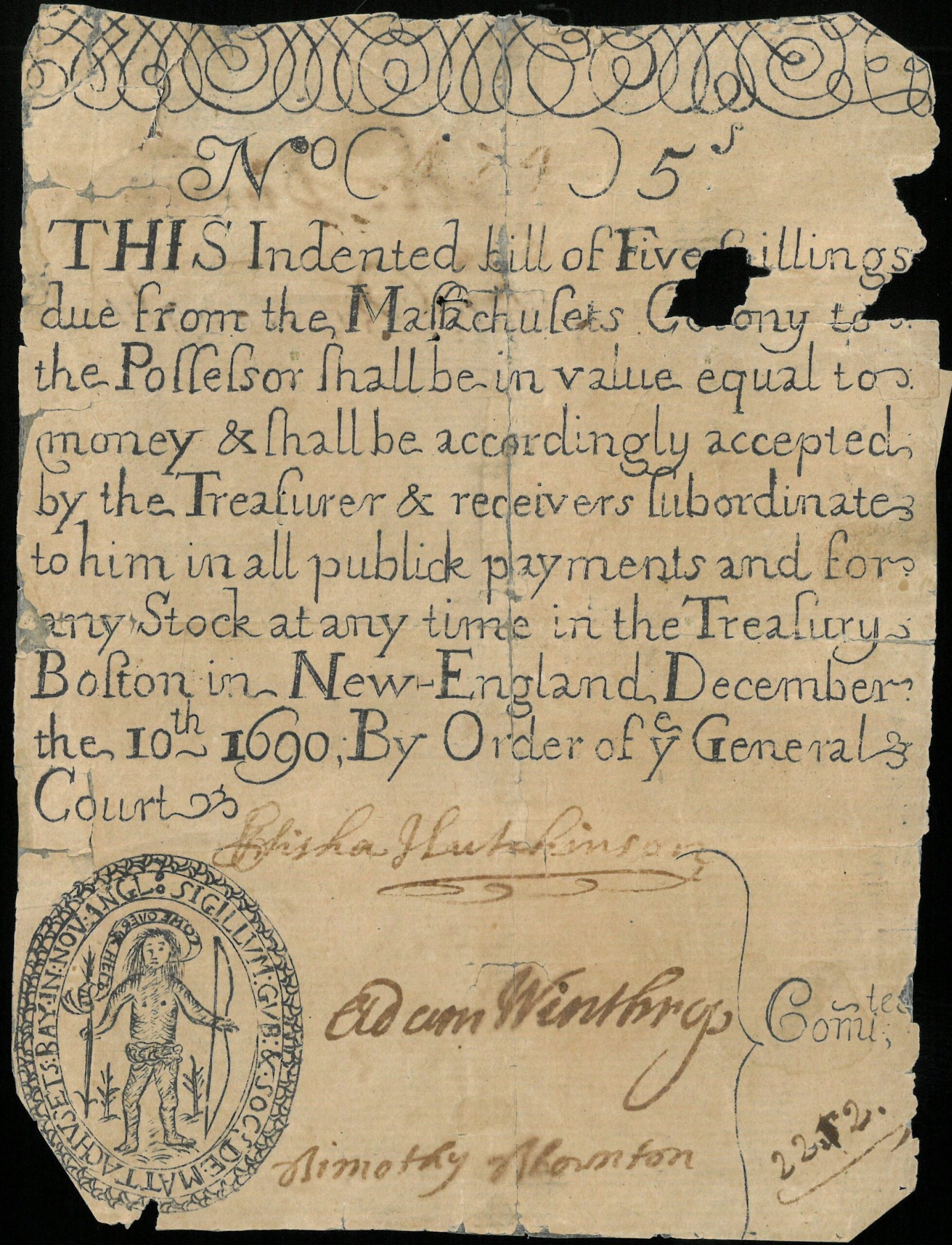

Americans’ experience of Barbary captivity came after the main European captivity period, when the new nation’s independence made it politically and economically vulnerable. After 1776, the U.S. was no longer under the protection of the British navy, and some believed Britain was encouraging the attacks as their own form of vengeance; meanwhile, the new nation lacked the funds and diplomatic muscle to readily negotiate the captives’ release. Barbary pirates captured several American ships in 1784-85, but the major public uproar came in 1793, when additional attacks ensued after Algerian vessels gained access to the Atlantic again, following a peace deal with Portugal brokered by Britain. Soon, up to 120 Americans were being held in Algiers. During this, the nation’s first hostage crisis, accounts of Barbary began to pour forth from the presses in every conceivable genre, including the print version of Slaves in Algiers. Some of these were published as part of efforts to raise money towards freeing the captives, a goal that that would not be achieved until 1796, when, after prolonged struggle and negotiation, the New England poet and U.S. consul Joel Barlow managed to secure their release for the astonishing sum of one million dollars.

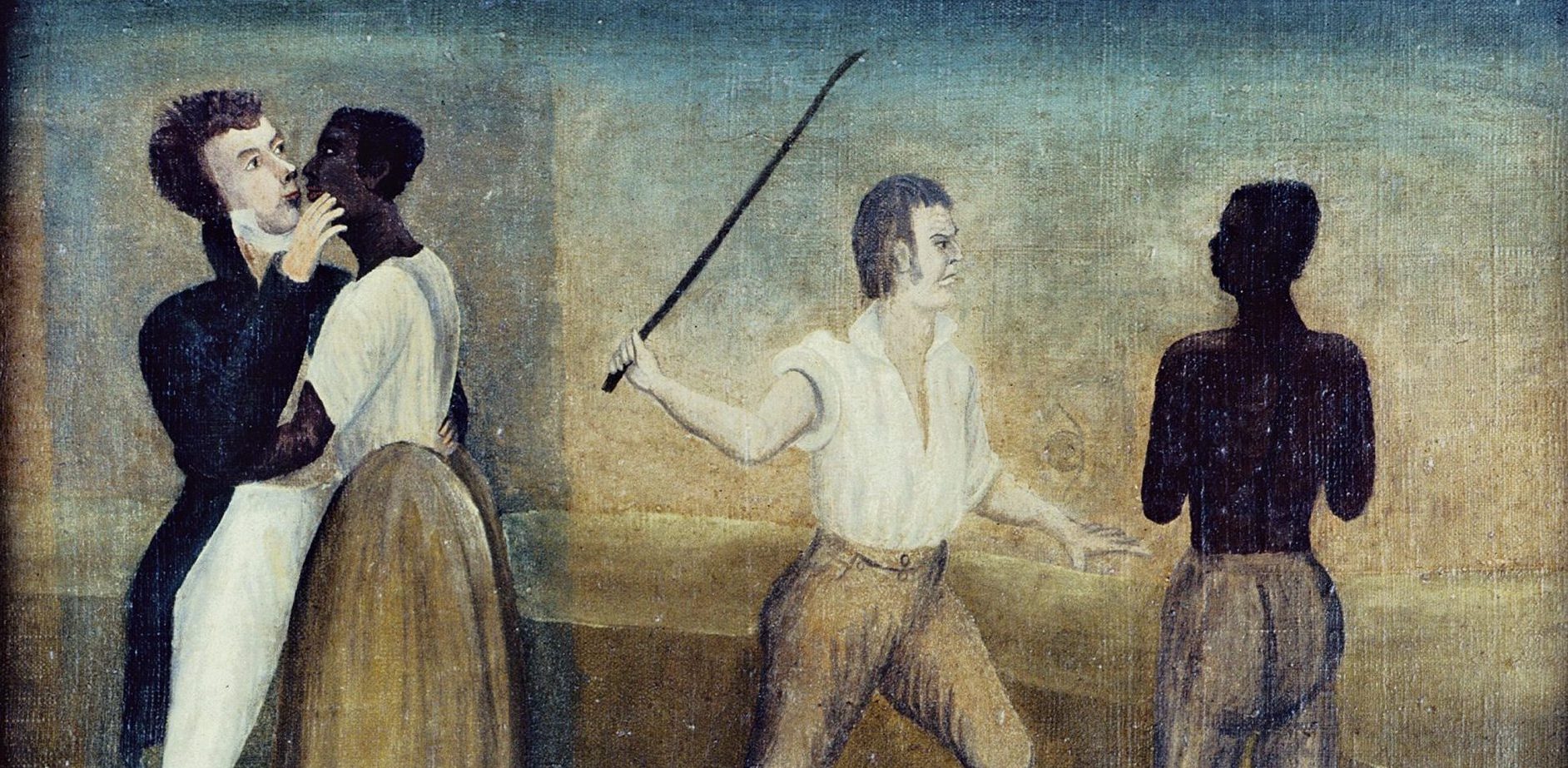

There is little documentation of Anglo-American women’s experience of Barbary captivity, and the existing narratives that focus on female captives appear to be fictional. Yet women occupy an important place in the American imagination of the Muslim world. Early writers emphasized the enclosure and sexual objectification of Muslim women, and representations of female Christian captives in the Barbary States similarly dwelt on their confinement and sexual vulnerability to predatory masters. Such images were both sentimentally affecting and covertly titillating, but they had political meaning as well. Historian Robert J. Allison explains, “Westerners saw the eighteenth-century Muslim world as a wicked mix of political tyranny and wild sex . . . [S]exual tyranny became the ultimate form of Muslim political tyranny.” This tyranny was exemplified through the image of the seraglio, where beautiful women were kept as “slaves to the tyrant’s lust.” The popular though spurious History of the Captivity and Sufferings of Maria Martin (1807), for example, culminates in an account of Martin’s two years of “close confinement” loaded down with irons and chains in a specially built dungeon. The frontispiece image of a topless, chained woman hints at the situation’s erotic implications and the narrative’s emphasis on the female sufferer’s helplessness. Though Martin at first “glow[s] with the desire” to show her fortitude in suffering, she eventually finds herself struggling with illness and depression, until her liberty is purchased and she is freed. Such a figure is almost perfectly reincarnated in the images of Jessica Lynch as captive: alone, broken, and immobilized in a Nasiriyah hospital (and, according to Rick Bragg, a victim of anal rape).

Such scenes of gendered oppression are alluded to throughout Slaves in Algiers, although Rowson’s emphasis is on moral and emotional pain rather than spectacles of physical suffering. Rowson dwells on the pain faced by both Muslim and captive American women, who are both in one way or another in bondage to male tyrants and their lusts. The play’s complicated plot involves American male captives who, as they seek freedom, are pursued by Muslim women, who wish to escape gender oppression by escaping with Christian lovers, and American female captives who teach and inspire the women of Algiers. The villains are two swaggering patriarchs: Muley Moloc, the Dey of Algiers, something of a Saddam figure characterized by his “tremendous whiskers” and “huge [scimitar],” and the rich and influential Ben Hassan, a English Jew turned Muslim renegade.

The American women, the older Rebecca and the younger Olivia, are pressured by Ben Hassan and Muley Moloc respectively to marry them. Yet they are given strength by their belief in liberty–both liberty as an American political principle, and liberty as it most directly affected women: freedom to live as a person rather than a sexual object and to choose a partner for love; freedom to be esteemed, as men are or should be, on the content of one’s character. Their strengths lie in their resistance to domination and their moral clarity, traits clearly exhibited by Rebecca when Ben Hassan argues that her commitment to liberty should extend to “liberty in love” (and hence encourage her to be one of his multiple wives): “Hold, Hassan; prostitute not the sacred word by applying it to licentiousness.” For her part, Olivia nobly plans to marry Muley Moloc to save her friends from death–then escape his power by “sink[ing] at once into the silent grave.”

Rebecca and Olivia have subversively indoctrinated the Muslim women around them with their beliefs; the most eager student is Ben Hassan’s daughter Fetnah, who says of Rebecca, “It was she . . . who taught me, woman was never formed to be the abject slave of man . . . She came from that land, where virtue in either sex is the only mark of superiority–She was an American.” Such rhetoric is, of course, really directed at Americans themselves, not all of whom accepted Rowson’s version of women’s high standing. Her contemporary William Cobbett harshly criticized Rowson’s play as the harbinger of a social revolution. “Who knows,” he speculated with dismay, “but our present House of Representatives, for instance[,] may be succeeded by members of the other sex?” Clearly, the “struggle for freedom” of the play’s subtitle is ultimately not so much that of the white captives as it is women’s struggle, or more broadly America’s struggle to live up to its political ideals by recognizing women’s contribution to the emerging nation.

This feminist commitment does not mean, however, that Rowson rejected traditional gender roles. It is hard to know if her insistence on women’s equality would have extended to female soldiers. Conversely, though, it is hard to see her not approving of women like Jessica Lynch and her comrades, who express female virtue much as she and other patriotic women of the period envisioned it, as a combination of love of country combined with devotion to family and other traditional female qualities. Like Rowson’s heroines, Jessica Lynch is plucky but ladylike, an aspiring kindergarten teacher, her tale of survival reassuringly linked to the story of her budding romance with a male soldier. It might not be going too far to see women such as Lynch as embodiments of the values of republican motherhood, the ideology through which the distinct but contained feminism of Rowson and other early national women was channeled.

Yet the vision of gender equality in Slaves in Algiers never escapes or contradicts the play’s imperialism. After all, emphasizing–indeed exaggerating–women’s freedom in America remains to this day one more way of insisting on America’s superiority in relation to Muslim countries. Slaves may show women teaching their sisters the value of liberty, but even this contributes to the dynamic of American Christians deciding they know what is right for the people of Algiers. In the closing scene, the formerly tyrannical Muley Moloc responds to the former captives who have promised him mercy, “I fear from following the steps of my ancestors, I have greatly erred: teach me then, you who so well know how to practice what is right, how to amend my faults.” He is urged to “sink the name of subject in the endearing epithet of fellow-citizen.” Everyone in Algiers must learn to become, in effect, Americans.

Reading the play in 2004, as we struggle with the continuing mess in Iraq, Rowson’s fantasy of neatly transferring democratic values to grateful recipients is all too ironic. And, post-Abu Ghraib, some of the play’s images are just a little creepy. I notice now, as I did not a year ago, how much the conclusion of Slaves in Algiers turns on the spectacle of abject Muslim men. Muley Moloc is stripped of his political and phallic power, reduced to thanking his former captives for their lenience. More obviously, Ben Hassan, who bears the weight of Rowson’s anti-Semitism as well as her anti-Muslim attitudes, is humiliated in implicitly sexual terms: unmanned by the slaves’ uprising, he seeks to escape by donning his wife’s clothes, and has a male Spanish slave fall in love with him. The Americans’ rather self-congratulatory declarations of mercy and might at the end are made possible by the very spectacle of disempowered prisoners before them.

Even Rowson’s vision of women’s equality cannot, it seems, escape the images of domination and submission the play has set loose. In the epilogue, Rowson plays with reversing the hierarchy of gender subordination, claiming that women who understand the real power of their sex “hold in silken chains–the lordly tyrant man.” She imagines what a female viewer might take from her play: “‘Women were born for universal sway; / Men to adore, be silent, and obey.’” Such assertions are, Rowson reassures us, only meant flippantly. But her qualification cannot entirely erase the thought that the lines allow a moment of breathing room: just what would it feel like for women to be the dominant ones, with men at our mercy? Given the images of confinement and sexual vulnerability always close at hand in the Barbary context, I wonder if these lines may not hint at the rush Lynndie England and others must have felt in Abu Ghraib. Whether or not they consciously saw themselves reversing the all-too-familiar image of the woman as victim, they were getting to experience themselves not only as Americans, but as women, on top.

Such images challenge us on every level. If once the theme of Barbary captivity forced Americans to confront their own investment in slavery, it now seems to demand we examine the very dynamics of domination as they permeate both gender and foreign relations. But as we confront the dilemmas of the present, the past remains illuminating. Rowson’s characters do not, after all, inflict corporeal vengeance or other cruelty upon their former captors. Once again the character Rebecca states it clearly: “Let us not throw on another’s neck, the chains we scorn to wear.” For all the signs of nascent American imperialism in her play, Rowson stood behind an idealistic vision of a world “where virtue in either sex is the only mark of superiority.” Without a virtuous citizenry, educated Americans of her era believed, the republic itself could not survive. And central to the period’s conception of virtue was a person’s capacity for feeling and sympathy for others–a capacity essential to understanding that the experience of captivity or imprisonment is truly terrible for all people.

Further Reading:

Susanna Haswell Rowson, Slaves in Algiers, or, A Struggle for Freedom, eds. Jennifer Margulis and Karen M. Poremski (Acton, Mass., 2000); Paul Baepler, ed., White Slaves, African Masters: An Anthology of American Barbary Captivity Narratives (Chicago, 1999); Robert J. Allison, The Crescent Obscured: The United States and the Muslim World, 1776-1815 (Chicago, 1995); Robert C. Davis, Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800 (New York, 2003); James R. Lewis, “Savages of the Seas: Barbary Captivity Tales and Images of Muslims in the Early Republic,” Journal of American Culture 13.2 (1990): 75-84; Paul Michael Baepler, “The Barbary Captivity Narrative and American Culture,” Early American Literature 39.2 (2004): 217-46; Malini Johar Schueller, U.S. Orientalisms: Nation, Race, and Gender in Literature, 1790-1890 (Ann Arbor, 1998).

This article originally appeared in issue 5.1 (October, 2004).

Anne G. Myles is assistant professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. She has published numerous articles on various aspects of dissent and gender in early America.