The pages of brothel guides contained sensitive information that unveiled the beauties of the underworld. The circulation of these publications—small booklets that cataloged the names of madams as well as addresses and descriptions of their establishments—was shielded from the light of polite society and handled with the utmost discretion, via mail, hidden in secret compartments of peddlers’ chests, and under counters or in the back of hotels and book shops, their sales hidden below mainstream business. Once possessed, they continued their life of secrecy, tucked away from prying eyes in the coat pockets of men. Knowing how or where to ask for these booklets gave men who were new to the cities the knowledge that allowed them to fulfill their lustful desires—though for a price.

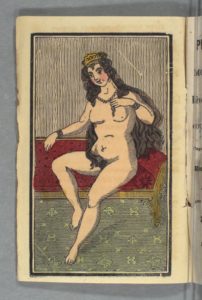

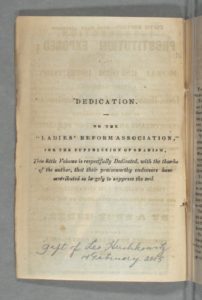

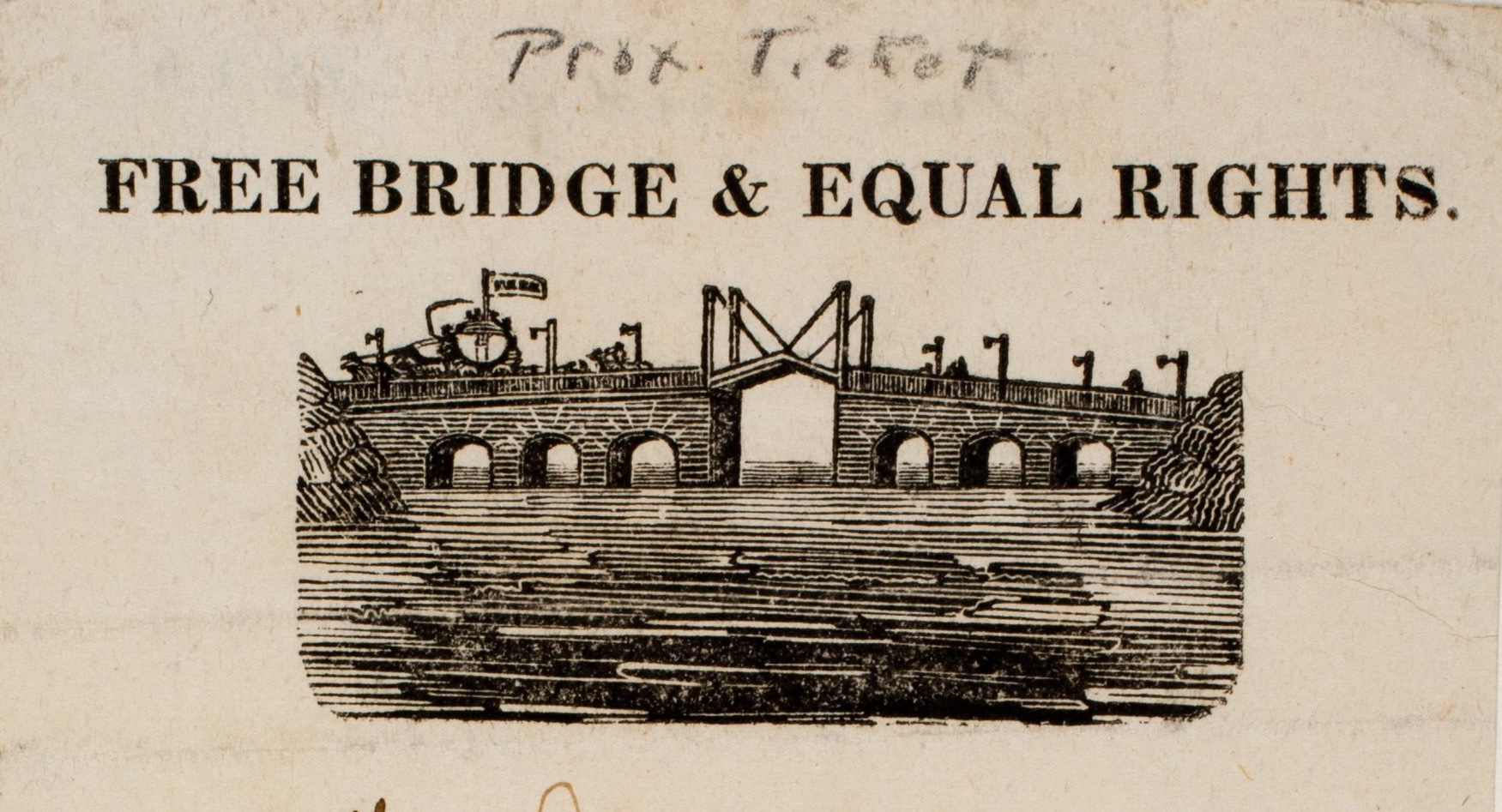

Throughout the nineteenth century, brothel guides directed men to brothels or sex workers in major cities. Brothel guides were illegal under common law obscenity and nuisance laws, which attempted to expunge lewd publications from public circulation. While some states adopted the English common law on obscene items, others created their own obscenity laws. This legal status led publishers to adopt different techniques and styles to obscure them from the public. Brothel guides tended to be small, making them easy to conceal. They also mimicked other types of publications to make it easier to hide the guides’ true purpose. The guides were explicitly constructed to impersonate bourgeois publications, potentially making middle- and upper-class readers more comfortable. During a time when the middle-class was growing and mobility was more possible, brothel guides adopted this language and imagery to speak to those who aspired to or already inhabited the middle class.

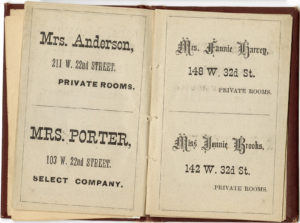

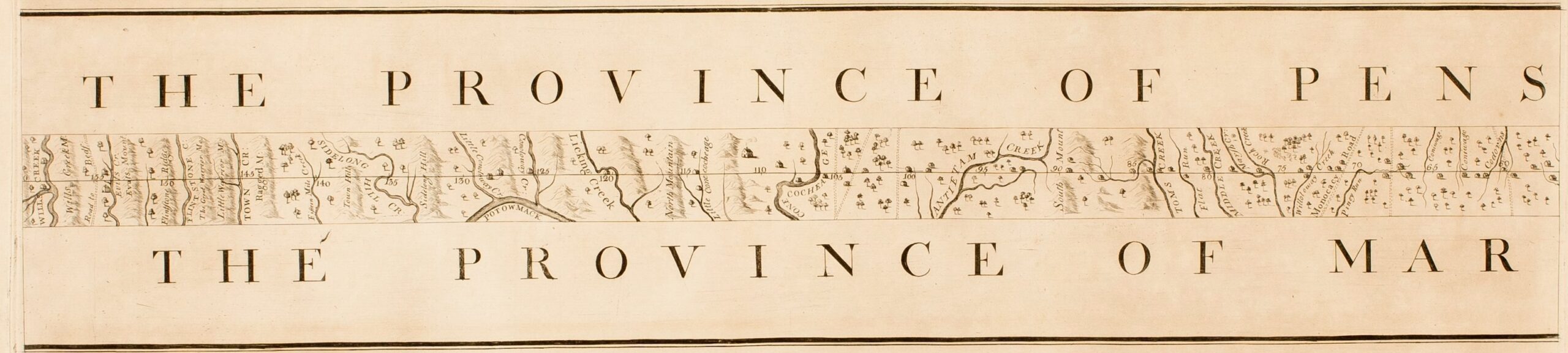

Brothel guides attempted to impersonate city directories, taking on similar characteristics that gave readers contact information and a description of the cities’ inhabitants. Printed city directories in America had been around since the eighteenth century and consisted of names, addresses, and professions of occupants of the towns and cities. Brothel guides emulated this type of print listing. They provided the name of the women, their addresses, and sometimes vague hints at their career, forcing the reader to infer that the women were not just offering lodging or food, but also sex. For example, the Gentlemen’s Pocket Directory for 1876-1877 of New York City and Philadelphia lists brothels as “Boarding Houses” with no further information that identify the listings as brothels. Comparing the “boarding houses” in the Gentlemen’s Pocket Directory to listings in other brothel guides, it is apparent these were not just offering lodging, as you can find the listings in other brothel guides. This particular guide fully adopted the characteristics of city guides. It listed not just brothels, but hotels, mail stations, pool rooms, post offices, and more.

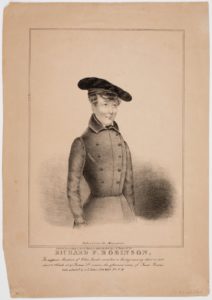

The nineteenth-century public was fascinated by titillating tales of the underworld. People expressed this intrigue by reading about gruesome crimes in the penny press or flash papers, which spotlighted “licentious” behavior like gambling and the activities of sex workers. For example, the January 14, 1843, issue of the Whip described a ball held by a well-known sex worker known as a Princess Julia. Widespread interest in such topics meant that they occasionally spilled over into mainstream press and became major news stories. One such occasion was the 1836 murder of sex worker Helen Jewett in New York City and the subsequent trial of Richard Robinson, a clerk accused of her murder. Whether reading the flash press or brothel guides, illicit publications allowed middle-and upper-class men to have a foot in two worlds.