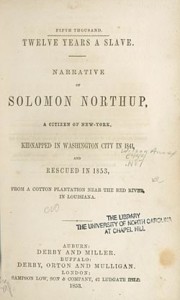

By the time the Union army reached Bayou Boeuf—the neighborhood where Solomon Northup, a free black man kidnapped from upstate New York, had been enslaved for twelve years—it had become a tourist destination. The federals accompanying General Nathaniel P. Banks on the march to Port Hudson, Louisiana, who had read Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave (1853) made a point of seeking out the plantation of Edwin Epps, the last, longest, and most notoriously brutal owner of Solomon Northup before he regained his freedom (fig. 1). On May 19, 1863, 2nd Lt. William H. Root of the 75th New York Volunteers, wrote the following in his diary: “We are in the district that formed the theater of Solomon Northup’s bondage”:

Old Epp’s plantation is a few miles down the Bayou and Epps himself is on the plantation, anoted man made famous of his owning Solomon Northup. Plenty of negroes are found about here who say that they knew Platt [Northup’s name while enslaved] well and have danced to the music of his fiddle often. Some who remember when he was taken out of the lot by the “Northern gemman.” Bayou Boeuf was then the witness of quite a scene which made a lasting impression on the minds of the poor darkies who saw the affair.

The story of Northup did linger, both on the bayou and in the memories of soldiers who traveled in those parts during the war. S. E. Chandler, a sergeant with the 24th New York Cavalry, wrote to the National Tribune in 1894 about Northup and his story, noting that “the book is now out of print, cannot be procured of any regular dealer.” However, he had found a copy of Twelve Years in a secondhand bookshop in Albany. Chandler recalled meeting “a number of returned soldiers who were with Banks on his Red River expedition who told me of having read the book at the time it was published (1854[sic]) and who visited the plantation of Edwin Epps, where Northup … passed years of his life. They told of seeing and talking with his former slave comrades, whose names were Uncle Abram, Wiley, Aunt Phoebe, Patsy, Bob, Henry, and Edward.” Chandler hoped that others who had visited Bayou Boeuf during the war might also write to the National Tribune with “a brief account of what they learned” about the world and the people that Solomon Northup had left behind.

The film serves to remind us what the war accomplished: the dismantling of the institution that cost Northup twelve years of his life.

As the soldiers who went looking for Edwin Epps well understood, to remember the Civil War was also to recall its antecedents and its outcomes—that is, the South and the nation as they existed before, during, and after the bloody conflict. The recent film version of Northup’s story, appearing in the midst of the Civil War’s sesquicentennial, exemplifies this broader understanding of war memory. Like the book before it, Steve McQueen’s Twelve Years a Slave points directly to the bitter roots of the conflict. The film also serves to remind us what the war accomplished: the dismantling of the institution that cost Northup twelve years of his life.

Recently, I began researching the editorial backstory to the first modern republication of Twelve Years a Slave, in 1968, and that edition’s translation into a feature film. It soon became clear that much of the press coverage of the film—which has focused on the film’s level of historical accuracy, and on how true it is to Solomon Northup’s account—has ignored the subsequent history of the story Northup told. Northup came to believe, when looking back at his escape from the bayou, that “all things were working together for my deliverance.” Little could he imagine that his published narrative would also experience redemption more than once in subsequent years.

Northup’s account reached the big screen after traveling the same hard ground of racial conflict that the nation as a whole crossed from the 1850s to the present. The book fell out of print after the Civil War and remained so through the nadir of race relations in the South and the rise of Jim Crow. It was not republished until 1968, in the midst of the Civil Rights movement, when historians had begun to reflect on the African American past in search of antecedents for the radical politics of the present. Now that the Civil War has once again become present in American popular culture due to the sesquicentennial, Twelve Years a Slave has resurfaced, this time in cinematic form.

That such a searing film would appear now seems fitting. While most contemporary textbooks discuss the role that slavery played in disunion, antebellum southern slavery is not often integrated into the popular memory of the war. Although important films about slavery and the Civil War have appeared since the 1960s—from Roots to Glory to Lincoln—none of these are so closely tied to the testimony of one person’s daily experience of slavery. It is the particularity of Northup’s story, as many historians have noted, that allowed him to so keenly reflect antebellum society at large and especially slavery’s hold over daily life in the South before the war.

The film’s attention to violence (a focus it shares with the original text) and to the plantation landscape in which such routine brutality occurred, de-sanitizes slick political justifications for the Civil War. Like Alexander Gardner’s grisly photographs of Antietam in 1862, Twelve Years shocks its intended audience with horrors that have largely been kept from the public eye.

As a work of both memory and memorialization, the film version of Twelve Years a Slave is perhaps the most powerful answer yet to the movie that became the archetype of the Civil War epic from its debut in 1939, David O. Selznick’s production of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind. The inverse of that unforgettable monument to a fictional yet fiercely remembered “Old South,”Twelve Years a Slave reminds us of what the Civil War really swept from American society.

The resulting film is clear-eyed and painful to watch, closely following the experience of its protagonist and taking relatively few liberties with the original text. Countless critics, writers, and historians have hailed it as cinema’s first honest look at the South’s “peculiar institution.” Writing in the New Yorker, David Denby declared it “easily the greatest feature film ever made about American slavery.” Were it not for the collaboration of two historians in Louisiana, however, McQueen’s film could not have become such a testament to what enslaved people endured before the Civil War.

In the spring of 1966, Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon contracted with Louisiana State University Press to republish what seemed to be an improbable story. Solomon Northup was a free black man living in Saratoga Springs, New York, in 1841 when he was lured to Washington, D.C., by two men posing as performers in need of Northup’s skill as a violinist. Awakening to find himself chained in a slave pen, Northup was quickly sent south to the New Orleans slave market, sold under the name of “Platt” to a man named William Ford, and carried to the Bayou Boeuf region of central Louisiana. There he remained in bondage for twelve years, much of that time to a cruel master named Edwin Epps, before he was able to reclaim his freedom.

On his return to New York, Northup arranged to tell his story to a lawyer named David O. Wilson. Like most slave narratives of this period, Twelve Years a Slave was both a condemnation of slavery and a much-needed source of income for its ex-slave narrator. Wilson does not seem to have had serious abolitionist leanings, but he was an aspiring writer and recognized a good publishing prospect in Northup’s story. Harriet Beecher Stowe had published her novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin the year previous, and it met with unprecedented success. The original 1853 edition of Twelve Years a Slave was dedicated to Stowe, who had been pleased to see Northup’s experience come to light. She noted the similarities between Northup’s ordeal and Uncle Tom’s, particularly the fact that Northup had been enslaved to a sadistic master (Epps) in central Louisiana, very near to where Tom suffered the abuses of Simon Legree.

Although Eakin and Logsdon became interested in the narrative independent of one another, Eakin saw it first. She recalled that she was about twelve years old when she first read Twelve Years a Slave. She had accompanied her father to Oak Hall Plantation (near Alexandria, Louisiana), where he had some business with its owner, Dr. W. D. Haas. Haas was the grandson of Douglass Marshall, mentioned in Northup’s account, who owned fifty slaves at Oak Hall in 1860. To keep the young girl occupied, Haas gave her the family’s copy of Northup’s story. She recalled being struck by the familiar names and places in the narrative.

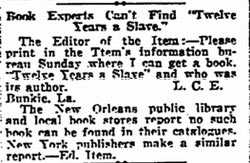

Despite her avid interest in Twelve Years a Slave, Eakin had a difficult time obtaining a copy of her own. The book had long been out of print, as a clipping in the New Orleans Item from 1922 attests. Someone from Eakin’s hometown of Bunkie with the initials “L.C.E.” placed an advertisement in search of a copy of the book and was told none could be had, even in local libraries (fig. 2). Eakin eventually found a copy in a secondhand bookshop in Baton Rouge. As a college student at LSU in the 1940s, she began tracing the life of Northup and apparently never stopped.

Perhaps it is not surprising that Sue Eakin’s is not the face most associated with the recent film adaptation of Twelve Years a Slave (fig. 3). In fact, most people would be hard pressed to consider the woman in her author’s photo (white, grandmotherly, with her hair set and a chain on her eye glasses) on the cutting edge of anything, much less that of African American history. Although it was clearly Eakin who did most of the sleuthing, with Logsdon’s help she brought the remarkable narrative of freeborn Solomon Northup’s ordeal in slavery back into print.

Just as Lt. Root penned his letter from a South soon to be free of slavery, Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon revived Northup’s narrative during another upheaval in American race relations. The political movements of the late 1960s brought with them a rising interest in African American history. At that critical point in a long racial struggle, in an age before digital archives put original nineteenth-century books at readers’ fingertips, Eakin and Logsdon made Twelve Years a Slave accessible to two generations of scholars and their students.

In doing so they became part of a long history of slave narrative publication and re-publication in American letters. With the rise of anti-slavery activism in the 1830s, the publication of slave narratives burgeoned. White abolitionists typically penned an introduction to the former slave’s account; many ex-slaves also relied on amanuenses (who often had heavy-handed editorial intent) to transcribe their stories. Some literary critics have seen this as an unequal relationship, and others see this same inequality in modern editions: the words of a former slave, so this critique goes, are never allowed to stand on their own, without the support of an editor to authenticate them.

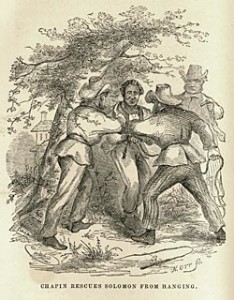

In the case of Northup’s story, however, the process of authentication was always something of a communal one, and it began almost from the moment of Northup’s liberation. Given the illegal nature of Solomon Northup’s enslavement, the effort to retrieve evidence of his sale and to retrace his steps commenced once he was redeemed. After a failed attempt to send a letter to New York and a near lynching (fig. 4), Northup found an ally in Samuel Bass, an itinerant carpenter with antislavery sympathies who got word to those in New York who could vouch for Northup’s status as a free man. A descendent of his father’s owner, Henry B. Northup, traveled to Louisiana to retrieve him, with endorsements and aid from Louisiana Senator Pierre Soulé and the governor of New York.

Both Northups then traveled to New Orleans, where they visited the slave pen where he had been held and the room in which William Ford had purchased him. According to the New York Daily Times, they also visited the office of a notary to “trace the titles of the colored man from Tibaut [Tibeats] to Eppes [sic], from Ford to Tibaut, and from Freedman [the New Orleans trader] to Ford—all the titles being recorded in the proper books kept for that purpose.” The elaborate system of notarial record keeping in New Orleans, which today fills an archive like no other in the country, helped Northup corroborate his own memory of events.

In later years, the accounts of Lt. Root and Sgt. Chandler, too, served to authenticate Northup’s story. And Chandler’s list of people who remembered Northup and his sudden liberation suggests that those who were enslaved with him also were willing to affirm both his story and its strangeness. The inclusion of a woman named “Patsy” on that list is significant since in Northup’s telling she had been the main object of abuse in the Epps household, caught between the sexual coercion of Edwin Epps and the violent jealousies of his wife. That Patsy may have been there still, with Epps, means the war could not have come soon enough.

White members of the Bayou Boeuf community—contemporaries and immediate descendants of those Northup had encountered—also chimed in regarding the accuracy of Northup’s memories. There is evidence that white planter families from the Bayou Boeuf community kept copies of the 1853 edition of Twelve Years a Slave in their libraries. According to Eakin, a family named Townsend “undoubtedly was one of those who owned one of the original editions of which there were a number still preserved.” Apparently the people of Bayou Boeuf were eager to see their community recognized in print, even if it appeared in the context of a truthful account of the brutality of slavery and the slave trade.

In the footnotes to the 1968 edition, Eakin reprinted parts of an annotation Dr. Haas had written on the flyleaf of the book in 1930, around the time Eakin first read the narrative. Dr. Haas’s inscription reflected the grudging admission of residents of the area that Northup’s narrative was accurate in its recounting of people and places in Bayou Boeuf: “This story is remarkable in many respects [—] that an uneducated negro after twelve years spent in slavery under a drunken overbearing Master could give so correct a narrative of his experiences is remarkable.”

By 1966, Eakin had completed years of research on Northup’s narrative, but convincing the editors at LSU Press that she was the right person for the editing job was not easy and, ultimately, not entirely successful. When she first approached the press about publishing Twelve Years a Slave, she was a married woman with children, a master’s degree, and an instructor’s position at a small regional state university. Eakin did not receive a PhD until 1978. “(Mrs.) Sue L. Eakin,” as she signed her letters, was not the highly credentialed male historian university presses preferred.

In one telling, Eakin approached the press and was rejected. When she tried again, the editors expressed mild interest. Unbeknownst to her, however, a young scholar at LSU-New Orleans (later, the University of New Orleans) with a BA and MA from the University of Chicago and a PhD from the University of Wisconsin, had discovered his own copy of Twelve Years a Slave, and had decided that it should be reprinted.

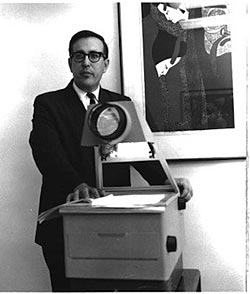

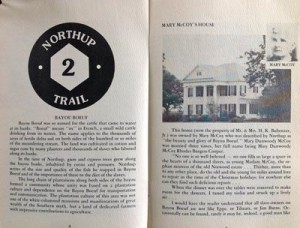

Joseph Logsdon first read Northup’s narrative when one of his students brought the book to class (fig. 5). The woman was a friend of the McCoy family, some of whom were mentioned in Northup’s account, and it was their copy she had brought for Logsdon to see. According to Northup, the young plantation mistress Mary McCoy was “the beauty and the glory of Bayou Boeuf” and a benevolent slave owner who held “about a hundred working hands, besides a great many house servants, yard boys, and young children” (fig. 6). In his first letter to her, Logsdon told Eakin: “The work came to my attention last fall when one of my students … brought me the family’s treasured (and humorously edited) copy of the narrative. After reading the fascinating book, I realized that it should be edited and republished.”

Both historians had gone to the press, within weeks of one another—Eakin with years of research in hand, and Logsdon with an interest in the subject matter and well-placed contacts in the field. After meeting Eakin and discussing a possible collaboration, Logsdon wrote to the director of LSU Press: “Her knowledge of the Bayou Boef [sic] region is truly impressive. There is no question in my mind that, working together, we shall write a much better book.” For Eakin, however, the decision to collaborate with Logsdon was not much of a decision at all, since she had little choice if she wanted to be an editor on the project.

They divided the work between them: Logsdon worked on the New York parts of the account as well as the introduction, and Eakin continued to research and write footnotes to the Louisiana portion. Together, they verified nearly every name, date, and landmark Northup mentioned in his narrative. John Ridley, who wrote the script of the film, told the New York Times that he relied upon the extensive notes in the Eakin and Logsdon edition to write the screenplay.

Logsdon’s most significant contribution, however, may have been his efforts to put Northup’s narrative in a larger context. Logsdon was aware that African American history was of increasing interest to publishers and within the academy. In his “Northup” file, he saved a clipping from theNational Observer dated March 21, 1966 (fig. 7), with the headline “A New Boom as Negroes Seek a Place in History.” The writer noted “the depth and diversity of the current Negro information explosion, a phenomenon that is inundating libraries and schools, spawning new businesses, and creating a sense of pride in heritage among thousands of American Negroes.” The Civil Rights movement and its fight for school integration, as well as “the emergence of Africa” in the popular consciousness, had created an “insatiable public appetite for information on Negro Life.”

In the same article, John Hope Franklin, then teaching at the University of Chicago, argued that “the Negroes’ contributions to the nation have been obscured by history, and deliberately so. The traditional view of the Negro that depicts him as irresponsible and shiftless was part of the apparatus used to uphold his degraded status, and justify the institution of slavery.” A “reexamination” of that view was underway, but not all of this new work was genuine. Pointing to the efforts of publishers and writers to turn a profit by quickly filling the void in black history, Franklin said: “There are people slapping anything at all to do with Negroes between two covers and making a profit on it.”

Logsdon must have seen the Northup project as one that would address Franklin’s concerns. The experience of enslavement narrated by one of the enslaved, a dramatic story filled with detail that could be verified and used by scholars and teachers, was the antithesis of the slapdash productions to which Franklin alluded. In light of Northup’s obvious intelligence, remarkable survival, and industrious frame of mind even under slavery (in addition to playing the violin at plantation parties, he saved his first master, William Ford, both time and money by devising a means for transporting timber down the bayou instead of over land), Twelve Years a Slave would contribute meaningfully to a rebirth of research and writing in African American history.

Logsdon also worked to promote the new edition among prominent historians. He enlisted the help of Kenneth Stampp, eminent historian of American slavery at the University of California-Berkeley, who agreed to write a blurb for the book (though it does not seem to have ever been used). Stampp called the narrative a “priceless document,” asserting that while Frederick Douglass’s narrative was the “superior” of the two, “in some respects Northup’s narrative is more valuable to the historian.” Because he had been born a free man, Northup (perhaps more so than Douglass) “tasted the bitterness of slavery.”

When the 1968 edition appeared—doubling the accepted canon of nineteenth-century slave narratives to two—it was as if Northup had offered up his story again, in another tumultuous era for race relations in America. A review for the Florida Historical Quarterly (whose blurb, strangely, still appears on the cover of the 2010 LSU Press edition) insisted that the book “should be must reading for every young Southerner. Only in accounts such as this can they understand the true nature of the curse which, more than a hundred years later, still hangs like a millstone around the neck of the South, hampering final emancipation for white and black alike.” Such a directive reflects the time and place in which Eakin and Logsdon reintroduced Northup’s remarkable story, delivering his account to an eager new generation.

If Logsdon provided the larger framework for Northup’s narrative, it was Eakin who reconstructed “the world of Solomon Northup,” to quote Logsdon himself. But in truth, Eakin’s relationship to her subject was not entirely academic—nor was it always objective. She seems to have been drawn to Twelve Years a Slave in large part because while it narrated Northup’s trials, the text also recorded a detailed history of her beloved Bayou Boeuf. In the early 1970s, for instance, she secured funding for a brochure called Backtracking: Twelve Years a Slave, which numbers the various sites of Northup’s enslavement and provides brief commentary on the people and places he encountered (fig. 8). This text serves as a (now mostly outdated) travel guide through the community where Northup was enslaved for so long.

Perhaps nothing so well illustrates Eakin’s familiarity with the world in which Northup found himself, however, than the map of “The Bayou Boeuf Country” she created with the help of a local cartographer named Rufus Smith (fig. 9). The names and property lines of plantation owners cluster on either side of the bayou, and the cleared land is ringed by swamps and mostly impassable forests. Like Northup’s narrative, the map is full of names and places, topographic notations, and marked routes between plantations. Eakin did her best to highlight Bayou Boeuf, its landmarks, and Northup’s journeys through it. But she was unable to render that same landscape from Northup’s perspective, that is, from the perspective of a free man who suddenly found himself enslaved in plantation country, far from a port or a coastline that might have afforded him swift passage home.

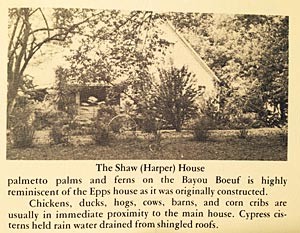

Sue Eakin’s mapping of Solomon Northup’s “world” and his journeys through it has been translated into three dimensions in Steve McQueen’s film. With the camera, he tracks Northup through what historian Walter Johnson describes as the “carceral landscape” of the mid-nineteenth century Lower Mississippi Valley, a vast territory of cotton and cane with few opportunities for escape. In Northup’s recollection, it was as though even the sun was beyond the reach of the bayou’s inmates: “In the edge of the swamp, not a half mile from Epps’ house was a large space, thousands of acres in extent, thickly covered with palmetto. Tall trees, whose long arms interlocked each other, formed a canopy above them, so dense as to exclude the beams of the sun. It was like twilight always, even in the middle of the brightest day.”

In McQueen’s film, elements of the landscape become characters in the story. He filmed oak trees, for instance, in long, watery shots of gnarled branches draped with Spanish moss and, at two points in the story, with the bodies of black men. In one scene, when Northup considers escape, the sweating indecision he suffers in the maze of scrub brush is frightening. When he then stumbles on a lynching—through which McQueen also evokes a more recent reign of terror in the South—the impassability of that space for a black man in the 1840s becomes plain.

Given how closely McQueen’s film hews to Northup’s account, Eakin would probably have been pleased with the film. But there is one important point on which Sue Eakin would have taken issue with McQueen’s version. It concerns the house where Epps lived—the very house where Lt. Root made a stop on his way to Port Hudson. Eakin exerted much effort to help preserve the Edwin Epps house, built with the help of Northup in 1852 (figs. 10 and 11). Since 1976, the structure has been moved twice and now sits, restored, on the campus of LSU-Alexandria. Eakin had found the house herself, after considerable searching: “I had a time documenting the house,” she wrote, “because I had mistaken it for another of the hundreds of thousands of old slave cabins which had once lined the Bayou Boeuf.” Eakin rightly pointed out that the house, a modest one, was “far more typical of plantation houses as known within the miles of plantations in the lower Red River Valley than the columned mansions ‘restored’ mostly with oil money after World War II.”

Much of the movie, in fact, was filmed on the grounds of the sorts of “columned mansions” to which Eakin alluded. The Felicity Plantation in Vacherie, Louisiana, plays the part of the Epps house in Steve McQueen’s movie and such a house, Eakin might have argued, would have been entirely too extravagant for a man who began his career as an overseer. In her Backtracking guide, she included a photograph of the P.L. Shaw House, a neighboring plantation to the Epps place with a nearly identical structure. The Shaw house was still in good repair at the time the photo was taken and probably offers something close to what Lt. Root and his companions found on Epps’s property in 1863 (fig. 12).

Eakin would have also appreciated the film’s high-profile release during the Civil War’s sesquicentennial. But she would have continued to point to our garbled understanding of the slave South and our even more confused attempts to remember the society that the Civil War upended. “It was here,” she seemed to say, “and here, and here.” The peeling houses and the bloodlines that persisted in Bayou Boeuf were also remains of the war and the last physical evidence of the antebellum society it (rightly) destroyed.

Further Reading

Two editions of Northup’s narrative have been published in advance of the film: Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave, ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. (New York, 2013); Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave, Enhanced Edition, ed. Sue Eakin (Longboat Key, Fla., 2013). The 1968 edition is Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave, Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon, eds. (Baton Rouge, La., 1968).

On the history of slave narratives, see Marion Wilson Starling’s The Slave Narrative: Its Place in American History (New Haven, Conn., 1981).

For critiques of Twelve Years a Slave as a book and a film, see David Denby, “Fighting to Survive:Twelve Years a Slave and All is Lost,” The New Yorker (October 21, 2013); Noah Berlotsky, “How Twelve Years a Slave Gets History Right: By Getting It Wrong,” The Atlantic.com (October 28, 2013); Jimmy So, “The ‘12 Years a Slave‘ Book Shows Slavery As Even More Appalling Than In the Film,” The Daily Beast.com (October 18, 2013); and Forrest Wickman, “How Accurate is Twelve Years a Slave?” Slate.com Culture Blog (October 17, 2013).

This article originally appeared in issue 14.2 (Winter, 2014).

Mary Niall Mitchell is Joseph Tregle Professor in Early American History and Ethel & Herman Midlo Chair in New Orleans Studies at the University of New Orleans.