There have been Shakers in the United States as long as the U.S. has been a nation. Never numbering more than a few thousand at any given time, the Shakers have contributed to American culture to a degree unmatched by any other small religious sect. With their American origins in upstate New York of the Revolutionary era, the Shakers are iconic within American culture for their innovation, work ethic, and sheer creative impulse. In all areas of the Shakers’ material output—from architecture and furniture to tools, housewares, textiles, and inspired drawings—a recognizable aesthetic emerged, renowned for its simplicity, elegance, and great beauty. But one area of Shaker creative output has received considerably less attention: music. Besides the ubiquitous “Simple Gifts,” first popularized by Aaron Copeland when he incorporated it as one of several folk themes in Appalachian Spring, Shaker music is virtually unknown today other than to a miniscule segment of scholars and Shaker enthusiasts. Yet, in music as in other areas, the Shakers exhibited astounding innovation and productivity. The quantity of original music produced by nineteenth-century Shakers is truly prodigious. From its earliest period in America, the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing—or Shakers—developed a tradition of music and dance unlike that of any other religious congregation in America.

American Shakers

Founded in England and led by the visionary Ann Lee, the Shakers began to stir the religious atmosphere of the northeast just a few years following their arrival in America as English refugees in 1774. They shared some impulses with other radical sects, such as concern over political corruptibility of clergy and the rejection of “papist” religious ritual, denominational creeds and doctrines, and oath-swearing. Distinctively, the group denounced sexual relations, and expressed its freedom from sin in physical form through exuberant group dances in worship, a practice that accounts for the derisive moniker “Shakers,” a term that the sect decided to embrace. During the last two decades of the eighteenth century, the Shakers drew hundreds of converts across upstate New York and the New England states, establishing nearly a dozen settlements of celibate believers living communally in self-supporting villages.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, Shakerism was making its mark on America. From radical conceptions of God, to gender equality, ecstatic dancing and celibacy, Shaker practices drew converts and detractors alike. As the faith developed more elaborate social organization in the growing eastern villages, the Shaker “Ministry” confronted the challenge of further growth. Beginning in 1805, the Shaker movement spread from its core region of upstate New York and adjacent Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Maine to the trans-Appalachian west. The experience of frontier evangelism gave rise to a dramatic phase in the evolution of Shaker music, stimulating the Shakers’ first production of hymns, a musical genre that would remain central to Shaker worship thereafter. However, western expansion was also critical to other aspects of Shaker musical development. Shaker doctrines involving gender and race equality and the dual-gendered nature of the godhead achieved their first formal articulation in the hands of Shaker songwriters in the west, many of them western men and women converts. This contributed to the infusion into Shaker music of rich and varied expressions of gender and collectivity without parallel in other American religious sects. Voices from the Shaker west also took active roles in finding fresh ways to articulate the notions of spiritual family and believers’ relationship to heavenly “parents.” Such concepts had been evolving in Shaker thought since the preaching of “Mother” Ann Lee, the sect’s visionary founder.

Shaker music

Thousands of music manuscripts survive, and individual songs number perhaps in the tens of thousands.

Although the Shakers’ material culture has received the most modern attention, arguably the most vital facet of Shaker life was not the production of material objects, but rather the production of music. The Shakers were—and are—first and foremost a religious movement, bound together by a unique theology and approach to worship. Music was the indispensable underpinning of Shaker worship, generating a unique aural environment and visual spectacle that drew onlookers by the hundreds or even thousands to Shaker villages from Maine to Indiana during the sect’s height and well beyond. Music helped to define and shape the dance practices that distinguished Shakers from other American sects. And music was among the Shakers’ most important cultural tools. It was through music that many of the vital complexities of Shaker doctrine were diffused and reinforced among rank-and-file believers. Music, with its catalytic capacity for emotional inspiration, helped the Shaker collective achieve the spiritual fervor that sustained the movement over generations. And because music could be even more mobile than Shakers themselves, it could be a potent tool for social cohesion as members of the sect migrated west. The sharing and circulation of music was the crucial instrument that allowed the Shakers to create and maintain a unified and coherent cultural identity across a thousand-mile territory in the early American republic.

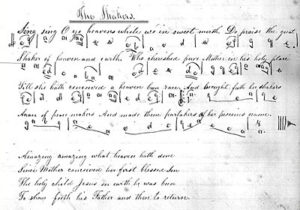

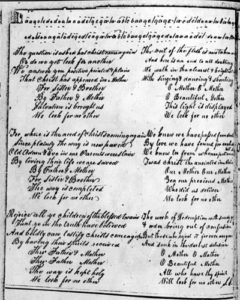

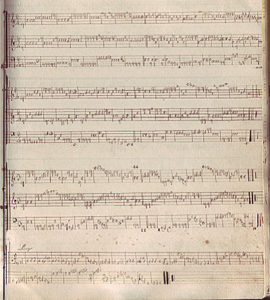

Ironically, two distinctive features of Shaker music—its usual form of notation and its prodigious diffusion in manuscript, as opposed to printed publications—have been largely responsible for shielding it from extensive scholarly attention. By the late 1820s, Shakers everywhere began to favor the use of a notation system in which lower-case letters of the alphabet represented notes of the scale. This replaced a hodgepodge of less effective earlier approaches, ranging from recording texts only and holding tunes in oral tradition, to using conventional music notation in round notes or shape-notes, to using capital letters or other symbols in place of musical notes. The “letteral notation” system adopted after the late 1820s dominated Shaker music everywhere for at least half a century. Thanks to the efforts of several gifted music theorists within the Shaker ranks, the system was formalized so that it could easily be taught (fig. 1). Consequently, hundreds upon hundreds of Shaker music manuscripts survive in which this letteral notation system predominates. Many of these manuscripts are substantial song books comprising hundreds of pages and containing a thousand or more individual songs. Yet because this rich corpus of music appeared to the uninitiated to be so much gibberish, it was consigned largely to obscurity until after the middle of the twentieth century. Also, the hymn books published by the Shakers in the early nineteenth century comprised—like the hymn books of many religious denominations—only hymn texts with no printed notation whatsoever. Consequently, folk musicologists examining American musical traditions in the early twentieth century had virtually no way to document the early music of the Shakers. Collections of Shaker music manuscripts were not then available to scholars. Among twentieth-century Shakers, few survived who knew how to interpret letteral notation any longer. Instead, the remaining Shaker communities were mainly using a set of late nineteenth-century hymnals printed by the Shakers using standard mainstream musical notation, whose contents represented a sharp departure from the music that had dominated the movement at its height decades before. Because of this singular set of circumstances, the landmark early studies of American folk music traditions sidestep the Shakers altogether. It has been left to later scholars to explore and analyze the rich and distinctive musical culture of the Shakers.

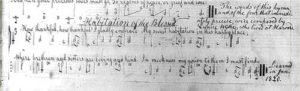

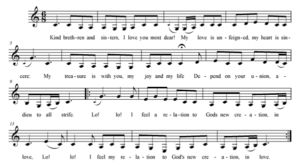

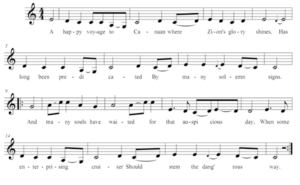

Shaker letteral notation was part of a group of related technical innovations that enabled early Shakers to record and disseminate an immense amount of music. Because it used letters of the alphabet, something the highly literate Shakers knew anyway, its use encouraged the production and recording of music across a far wider swath of the Shaker population than might have been the case had traditional music notation been employed. Use of a five-line staff was optional. The Shaker music theorist Isaac Newton Youngs devised a five-line staff pen around 1834, and many Shaker music manuscripts do place letteral notation on a staff (fig. 2). But just as often, tunes simply appear as strings of lower-case letters interlined with words (fig. 3). The problem of how to convey the movement of the melody stimulated another innovative feature of Shaker notation, namely, the graphic meandering of the letters on the written page. Melodic movement is signaled by the meandering of those strings of letters uphill or downhill relative to the horizontal plane of each written line. Still other music scribes developed diacritical markings to indicate movement of intervals within a melody, allowing songs to be notated using simply strings of letters and their markings in straight horizontal lines, below which the song texts would appear (fig. 4).

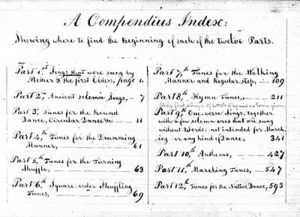

But while the technical innovations of letteral notation set Shaker music apart in some obvious respects relative to other forms of early American music, they do not represent Shaker music’s most significant features. Far more profound are the social and performative innovations. The Shakers engineered a wide range of entirely different musical genres to complement the various aspects of worship—wordless dance songs, hymns, one-verse songs, “occasional” songs, anthems, inspired songs. These genres developed over time, as Shakerism itself evolved. Collective worship might employ many genres simultaneously, often in the same meeting. Some of the older genres never fell entirely out of use but continued to be used alongside much newer ones. The “Compendious Index” from a comprehensive 1845 manuscript compilation by Shaker Russel Haskell of Enfield, Connecticut, reflects the range of Shaker musical genres at mid-century (fig. 5).

During the Shakers’ beginnings in 1780s New England, music consisted mostly of wordless improvised melodies, to which were fitted vocalized syllables or “vocables” (such as “lo-lo” or “vum-vum”). This sort of non-verbal singing freed the worshippers both for group dancing and for the experience of spiritual extremes, unencumbered by complex lyrics. The use of such tunes to accompany dance continued unabated for nearly a century in some Shaker communities. Russel Haskell, the first Shaker to historicize Shaker musical tradition, writes that in the earliest period, “the young converts were led to sing, some of the time, such as they had been accustomed to sing before they believed.” Indeed, the Shakers integrated some “worldly” tunes, especially in the Shakers’ first generation. Some of the tunes adapted to the gender-divided collective dancing bore enough superficial resemblance to popular tunes of the early republic that detractors declared that Shakers worshipped to the bawdy strains of “Yankee Doodle” and “Black Joke.” Eventually, wordless tunes were subdivided according to time signature for different categories of dance, with most taking on 2/4 or 6/8 time for marches and “back-order” dances, versus shuffles and circle dances, respectively.

More innovations ensued as Shakerism entered the nineteenth century. The use of hymns with lyrics seems to be a common enough feature of American sacred music. But for the Shakers, hymn lyrics were an innovation that emerged as the first flush of northeastern expansion gave way to more systematic and wide-ranging missionary work mainly targeting the trans-Appalachian west. The wordless songs alone could lead to spiritual excesses among young believers that were difficult to reign in. During the early western expansion, worship with young converts could easily get out of hand. But hymns could convey Shaker doctrine and history to people who had never seen Shakers before, while at the same time encouraging orderly deportment among exuberant converts. As a proselytizing tool, lyrics could help convey the themes and nuances of Shaker doctrine, as well as the powerful narrative of the Shakers’ short but dramatic history, in ways that wordless dance songs could not possibly accomplish. Several Shaker leaders involved in codifying doctrine also happened to be capable poets, and this contributed to a thriving hymn enterprise. While familiar tunes from hymnody or balladry were sometimes adapted by the Shakers and fitted with new lyrics, new tunes also emerged, albeit with strong folk music influence.

Other innovations followed. Anthems first emerged among eastern Shakers sometime in the early 1810s. Anthems consisted of lengthy prose texts set to continuous, meandering melodies. Shaker anthems appear to be related to the choral anthem tradition found in New England hymnody of the late eighteenth century, in which prose texts often of Biblical origin are set to long, wandering arrangements in three or four-part harmony. In Shaker worship, it is probable that solo individuals sang the anthems, as inspired and scripture-based exhortations to the assembly of listeners. Common anthem motifs include the use of “spirit language” phrases, or one form of what the Shakers considered to be “speaking in tongues,” integrated into spiritual exhortations (such as, “But if ye do as ye are taught by my salinda va, sa lac navoo ar tala van, not one of them shall fail,” a typical phrase from an 1830s anthem). Another common anthem motif was the spelling out of key words in sung phrase (i.e., the sustained spelling of “P-E-A-C-E” or “P-R-A-I-S-E” over a drawn out melodic phrase).

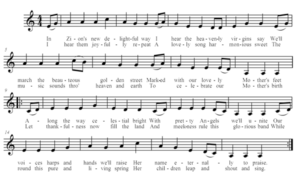

Obedience, order, and union were all highly valued in Shaker life, and one musical innovation that seemed to underscore them was unison singing. While unison singing was by far the dominant mode until the 1870s, harmony was not unheard of. Close examination of some music manuscripts produced by western Shakers in the 1830s reveals a surprising number of hymns and wordless songs recorded in three-part harmony, suggesting that harmonized singing was practiced in specific communities and favored by specific Shakers (figs. 6 and 7). An eastern Shaker experienced “gifts” of harmony in the form of clumsily harmonized anthems in the 1840s. But it was not until the 1870s, when the some of the Shakers’ own unique musical innovations began to be laid aside, that vocal harmonies became a regular feature of Shaker singing.

The music of Shaker worship has never involved any use of musical instruments. The Shakers, like other primitive Christian denominations, have favored the human voice as “the sacred harp” for creating worshipful musical expression. A capella singing tends to set songs in keys of convenience rather than according to absolute pitch, and Shaker singing is no exception. However, for the ease of recording the songs in letteral notation, Shakers developed the practice of recording all major key tunes in C, to prevent the need to integrate sharps and flats (fig. 8). For minor key tunes, Shaker practice is divided. Some manuscripts set virtually all minor tunes in A minor, or the “aeolian” mode (figs. 3 and 4), while others use D minor, or the “dorian” mode (fig. 9). This division reflects a debate that was carried on during the 1840s between two dominant Shaker music scribes over which mode constituted the true “natural” minor. Again, the purpose was to obviate the need for sharps and flats.

In a social sense, Shaker music emerged as a form of democratic expression within the Shaker collective. Shakers permitted music to grow organically from within each community. In sharp contrast, other religious denominations of the nineteenth century removed music production from practitioners’ hands and redirected it to distant, institutionalized boards and publishing houses. For the Shakers, the process of producing music was deeply embedded in the everyday lives of all individuals, in all communities, east and west. Every believer possessed equal potential for experiencing a musical “gift” that could be integrated into the ever-growing repository of music. Ironically, for a sect in which rigid leadership hierarchies helped to impose “Gospel Order,” music production was remarkably free of hierarchical control. Musical gifts could issue from the humblest believer to those holding higher offices. Songs came from women and men, teenaged to elderly, white and black, mixed-race and immigrant believers. And during many periods of Shaker history, songs poured forth spontaneously in seemingly endless quantities, sometimes in the very midst of worship. The contrast with most American religious sects could not be greater. One could hardly imagine a routine worship service in most American denominational settings in which an individual congregant would feel freed and empowered to deliver a newly inspired song on the spot with complete spontaneity, teach it to fellow congregants, and perform it collectively. Yet such was the norm in Shaker worship for more than fifty years. And far from being considered trivial or banal, such music was valued, carefully learned, enthusiastically shared, and meticulously recorded for posterity.

Shakers, the most dispersed communal society in American history, also shaped their music to meet the challenges of geographic separation. Creating and maintaining gospel union lay at the core of Shaker identity, but accomplishing that across a span of a thousand miles was daunting indeed. Yet, because music was democratized and organic, it could be applied more flexibly and prescriptively to suit a range of uses, spiritual and cultural alike, in the life of any Shaker community. Manuscripts reveal songs carefully produced by the hundreds to mark specific holidays, visits, funerals, and other cultural milestones. Songs could also act as custodians of Shakers’ intimate friendships, helping many Shakers living in disparate communities sustain friendships across vast distances for many years. Songs were regularly transmitted in correspondence, carried by visitors, and given as gifts, in addition to being bound into printed collections. While one Shaker in Kentucky might have little available opportunity to feel in “union” with another in New Hampshire, shared songs allowed Shakers to communicate with distant strangers in a common language. In some cases, believers tried to engineer specific days and times when a given song would be collectively performed by a multitude of Shakers as various locations. In one example, believers across both East and West were directed in 1835 to pause on March 1 at six o’clock in the evening and sing two specific hymns to mark the birthday of Ann Lee, because, “the consideration that all the faithful in every Society throughout the land are, at the same time, engaged cannot fail to . . . animate the zeal and cheer the spirits of all her faithful children.” Similarly, one hymnal records that an 1850 New Hampshire song called “All Glean With Care” was “appointed to be universally sung among Believers, Sept. 1, 1850.” And many mid-century hymnals, eastern and western alike, record a song entitled “Saturday Evening,” which promoted a shared period of collective spiritual reflection across the entire Shaker world as the Sabbath neared.

The Shaker music enterprise moves west

On New Year’s Day, 1805, three Shaker missionaries set out on foot from New Lebanon, New York, the spiritual center of the Shaker world. Their destination lay somewhere beyond the Appalachian mountains in the region of the Ohio Valley. News of the remarkable “Kentucky Revivals” had reached eastern cities, and the Shakers hoped that the region’s apparent religious fervor might augur well for a further expansion of the Shaker movement. A journey of nearly three months took the missionary trio through the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, into Tennessee, across the Cumberland Gap, through celebrated revival sites of central Kentucky, and into southwestern Ohio. It was at Turtle Creek in Warren County, some twenty-five miles north of Cincinnati, that the first converts were gathered and the seeds of a permanent western Shaker enterprise were planted.

Music was a crucial component of the Shakers’ westward enterprise. Although the Shakers were just one among many sects active in the revivals of the trans-Appalachian frontier, Shaker worship was nonetheless distinctive for its practices of ecstatic collective singing and dancing. The missionaries had to be effective singers and dancers in order to teach the characteristic features of Shaker worship to entirely new audiences. Also, the missionaries were conscious of their goal of establishing distant communities that would nonetheless be part of one larger collective, with common values, common beliefs, and a common heritage. In the trans-Appalachian west of 1805, few had heard of Ann Lee. The Shakers promoted radical ideas: a dual-gendered godhead, a Christ-spirit that had been manifested in a working-class woman immigrant from Manchester, England, the renunciation of the marriage bed and all sexual relations, the notion of undoing biological family ties to live collectively in spiritual families with shared community of goods, and the conviction that one could confess sins to an elder and thereafter live free from sin apart from the “world’s people” in a separate sphere of “Zion” on earth. In 1805, these ideas had not been formally written down and circulated in any printed tract, except for the lurid distortions and misinformation published by detractors. It quickly became clear that hymns could serve a vital function of transmitting Shaker beliefs and ideals, along with some background of the sect’s short but colorful history. And because the content and structure of hymns was limited only by poets’ imaginations, hymns could also serve a range of didactic functions, inculcating western converts in the expectations of communal life, Shaker work ethic, cultural norms ranging from dress to diet to entertainment, and nuances of Shaker social relations.

During the opening years of the western Shaker missionaries’ work, large groups of converted families were “gathered” at many different locations throughout the region. To assist the original three Shaker missionaries, more eastern Shakers were sent. The eastern Shaker Ministry at New Lebanon, New York, carefully selected each missionary dispatched to the west. Doctrinal grasp, spiritual zeal, charisma, hardy constitution, singing ability, organizational skills, and writing abilities were all considered. In 1806, the first eastern Shaker women arrived, a crucial step in successfully establishing the Shaker faith in the west. Though most converts—men and women alike—made their initial confession of faith to a male Shaker preacher, the difficult work of beginning to transform converts’ households to conform to Shaker ideals needed the guidance of seasoned Shaker sisters. Also, experienced eastern sisters could better counsel women converts on balancing the exhilarating exertion of Shaker worship—which sent women’s hair and clothing flying into disarray—with the need for modesty and decorum. In just a few years, around two dozen eastern Shakers—women and men in equal numbers—were sent to the western region. At each of the settlements organized under communal covenants, the easterners were assigned chief leadership positions of elder or eldress, with western men and women mostly assuming secondary leadership assignments.

Western convert Richard McNemar was instrumental in persuading the eastern Shaker ministry to collect and publish the first set of Shaker hymns. As a singer, poet, and preacher, Richard had joined in the evangelism process after his own conversion in 1805, partnering with the Shaker missionaries and traveling throughout the region to spread the Shaker message to new audiences. Richard was also a deeply erudite man, fluent in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, with a commanding knowledge of scripture. He quickly set his pen to the composition of dozens of hymns laying out all aspects of Shaker doctrine and theology. As the eastern Shaker music scribe Russel Haskell later wrote, “Our first hymns originated among the young believers residing in Ohio or in some of the western states.” Correspondence between eastern and western Shaker leaders during the crucial opening years of the west reveals plans to collect these newly composed hymns, print them, and share them among the eastern Shaker communities. Other Shakers with poetic and musical abilities joined the hymn writing enterprise, including several easterners such as Issachar Bates, the Shakers’ most charismatic frontier preacher who had been part of the initial missionary trio dispatched to the west. By 1812, the eastern Shaker ministry published the sect’s first hymn book, Millennial Praises. Of the 200 or so hymns it contains, the majority were composed in the west, and over half were the work of Richard McNemar. Millennial Praises represented one of the earliest published expressions of Shaker theology. The other major printed theological treatise from this period, Testimony of Christ’s Second Appearing, was also authored in the west and bore the strong influence of several of the western converts. Clearly, Shakerism’s western expansion was noticeably shaping both the movement’s music and its theology.

Babes, mothers, and virgins

Shakers in the west were deeply conscious of being a branch of the broader Shaker spiritual family. All of Shaker culture was predicated on the notion of family, reflected in the forms of address for leaders and rank-and-file believers—Mother, Father, Sister, Brother. Stories of Mother Ann Lee, as recounted in hymns, played a vital role in reinforcing the collective identity of the Shakers across the various communities. Because the western converts’ experience of Shakerism was far removed, both temporally and spatially, from the scenes involving Mother Ann and the other Gospel Parents, narratives contained in hymns were all the more important. Also important was the guidance of the eastern Shaker men and women, who represented a physical link among the distant portions of the Shaker family, and many of whom recalled Mother Ann personally. While Shaker leadership was equally divided between genders, the role of “Mother” was particularly potent. “Mother” was a title reserved for a select few, including the female “lead” of the New Lebanon Ministry.

Shakers in both east and west were acutely aware that their sect’s entirely non-sexual understanding of gender and family constituted probably the biggest single distinction between Shakers and the larger world. Reverence for the concept of motherhood, together with all sorts of family-based metaphors, were woven into the fabric of Shaker culture at all levels, from everyday conversations to correspondence, worship, poetry, and hymns. Letters between east and west were replete with expressions of maternal love: “Therefore you are Mother’s children—and are near her heart. Yea she loveth you as her darlings,” and “Mother’s little children here have a desire to acquaint their spirits with the spirits of Mother’s pretty little children in the east” are typical passages. Familial figures of speech could become excessive and even turn to outright childishness. In an 1818 letter from South Union, Kentucky, Eldress Molly Goodrich, a native easterner, addresses her desire to visit the east and see the Ministry female lead, Mother Lucy Wright. In it she reveals the childish banter exchanged between herself and Elder Benjamin (“Benny”) Seth Youngs:

Now don’t you think it would be very comforting to little Molly to have the privilege to be in the good old first families meeting once more? Yea … ask the baby’s pretty Mamma to let it come home so it can get the chance to suck a little once more; yea … we think that would be a very good way to fat up the poor little Babe. For that little Benny since he has been home & had such a good chance to feast has got as fat as a little pig … I tell him every once in a while that I mean to go home too, and he says nay, Mother won’t let you got home but she lets me go home, for she loves me better than she loves you; then I’ll say nay she don’t, she loves me the best; and so the children goes on.

Biblical references to virgins preparing to receive the bridegroom also served as sources of another figure of speech common in Shaker discourse. All Shakers, men and women alike, thought of themselves as “virgins” espoused to the Christ-spirit. Biblical passages describing the virgins’ preparation of fine garments for wedding nuptials were grist for a great many Shaker hymn texts. Especially in the Shaker west, references to garments were popular and could be read on several levels. From the beginning, western Shaker converts had sought to signal their devotion by dressing like their eastern counterparts. In a frontier setting where cloth was scarce and produced only through great labor, one’s garments were important possessions, and abundant clothing was a sign of wealth. Among the Shakers, gifts of clothing sometimes passed from east to west, with great impact on the recipient, even if the fit was less than perfect, as is evident in a note of thanks written by a western Shaker sister in Indiana territory:

I feel myself honored … for the beautiful garment you sent me. O what a pretty thing—Sure enough what a beauty! I never had so much as dreamed of this … But if I could do with it as little girls of the world do with a present of their Mother’s garment, to have it laid up for them till they grow big enough to wear it, and so look at it once in a while to see how pretty it looks. But but alas! This will not do! For it is too little now, or else I am too big—and yet it was sent to me to put on and wear. And I must and will do it …

Serendipitously, among the early missionaries dispatched to the west were a few gifted poets and singers. Chief among these was Issachar Bates, a member of the first missionary trio, who had been a long-time choirmaster and published poet before becoming a Shaker in 1801. Likewise, some of the earliest western converts included men and women who were already talented hymn writers, as well as enthusiastic singers. Richard McNemar, a leading “New Light” preacher (the term applied to several Kentucky preachers who left the Presbyterian denomination in 1803 when they believed that new revelation or “light” was leading them to deviate from established doctrine) of the region who converted about a month after the Shakers arrived, had taught singing schools and written poetry. Samuel Hooser, an early Shaker convert at the Mercer County, Kentucky, location that became the robust village of Pleasant Hill, had been a Methodist minister from North Carolina with longstanding interests in hymn composition. Hooser, who entered the Shakers with a group of other family members, was among the chief songwriters at Pleasant Hill for decades, together with his niece Hortency Hooser, who also wrote abundant songs. In western Kentucky, the very musical Eades family converted, including Sally Eades, a young mother with an infant named Harvey. Both Sally and Harvey Eades would contribute an enormous quantity of hymns and songs to the western Kentucky Shaker settlement of South Union. Within the work of these western Shaker composers can be found hymns and songs whose themes include family and motherhood, virginity, and the wearing of fine garments.

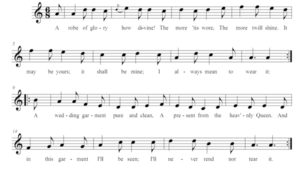

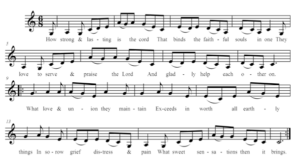

The title of this essay comes from a hymn called “Do Or Die” written by Issachar Bates. Taking the perspective of a western Shaker, it incorporates familial and maternal metaphors, including a mother nursing her infants (song score 1).

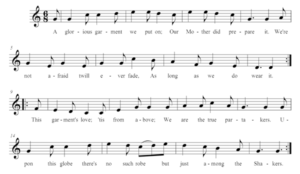

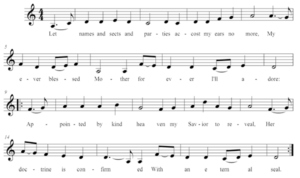

Among the virtually countless hymns composed by Richard McNemar are two that take the form of ballads presenting aspects of Shaker history, including episodes from the life of Ann Lee. Significantly, early correspondence from the Shaker west includes specific requests for historical detail from the easterners so that western converts might better be oriented to their spiritual heritage as Shakers. Such detail was probably intended for integration into these hymns (song scores 2 and 3).

“The Wedding Garment” reflects an early point in the western Shaker experience, probably circa 1807. It integrates scriptural references to the virgins preparing to receive the bridegroom together with numerous garment metaphors also drawn from scripture. Its strong melody also incorporates a wordless phrase, indicating that dance may have accompanied the singing of this hymn (song score 4).

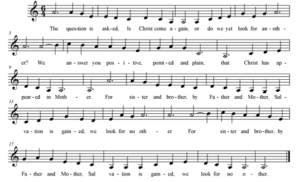

“Is Christ Come Again?” is a doctrinal hymn written by Sally Eades of South Union, Kentucky. Eades was among the earliest converts in far western Kentucky, and her family had originated in Virginia. Nothing is known of her earlier education or musical knowledge. But her complex hymn texts number in the dozens, and many of her songs are recorded in three-part harmony. This one displays a sophisticated understanding of the dual-gendered godhead, along with the parallel gender structure of Shaker authority and membership tiers (song score 5).

Hortency Hooser, a Pleasant Hill sister, was probably around thirty years old when she wrote the popular song “In Love.” It uses a repeated refrain, a somewhat more common feature of western Shaker hymnody (song score 6). Hooser also produced “Golden Street,” a joyous vision of Zion filled with gorgeously attired virgins (song score 7). Her uncle Samuel Hooser produced several hymns circulated and sung throughout the Shaker world for nearly a century. One of his many hymns alludes to the strong cord of unity binding the Shakers west and east, a popular theme in Shaker hymnody (song score 8).

Thousands of Shaker songs are unattributed to any specific individual, but bear attributions of a place of origin. Such is the case with two songs that present the popular theme of spiritual garments or “robes.” Both songs are classified as dance music, are identified as coming from Ohio, and appear to date to around 1815 (song scores 9 and 10).

Today the Shakers are perhaps best known for the many distinctive things they crafted, built, and manufactured, from furniture and cabinets to architectural structures and household tools. Renowned for their simplicity and elegance, Shaker-made objects are presumed to contain some transcendent vestige of the fervent spiritual movement of which they were a part. And perhaps they do. After all, the value in the marketplace of Shaker-made objects points to that possibility.

And yet, Shaker songs are the one completely genuine Shaker-made creation that can be acquired at virtually no cost, apart from the effort required to locate and view them in scores and manuscripts, sing them, and learn them. They are every bit as Shaker-made as any finely crafted chair, cabinet, basket, or oval box, because music has always been just as central to the Shakers’ cultural output as any material object. Indeed, because Shakers produced their music precisely to enliven and guide their spiritual lives and collective worship, it reflects core Shaker values far more directly than any other aspect of their creative practice. Yet today only a handful of Shaker songs are widely known.

A Shaker sister wrote in the 1840s of a vision in which Ann Lee reassured her that the enormous time taken to learn and record so many songs was not wasted time. In the vision, Ann Lee declared that the time would come that these songs would be “needed” for the edification of people yet unborn. With renewed public interest in early forms of American folk music, perhaps that time has come. This obscure music still has the power to awe, impress, astonish, and inspire a contemporary audience. The Shaker movement remains without question a powerful and even iconic element in American folk culture. Because the Shakers’ music was among the sect’s most potent forms of spiritual expression and creative output, it deserves fresh attention.

Further Reading

Efforts by non-Shaker scholars to document Shaker history began over a century ago with the work of J. P. MacLean, an Ohio historian who began collecting Shaker manuscripts and talking to aging Shakers at the dwindling communities in southwestern Ohio. His book, Shakers of Ohio (Columbus, Ohio, 1907), remains the most comprehensive descriptive history of the Shaker west, though the information MacLean presents is not referenced. In the mid-twentieth century, Edward Deming Andrews produced the first comprehensive history of the entire Shaker movement, The People Called Shakers: A Search for the Perfect Society (Mineola, New York, 1963). A more recent general history is Stephen J. Stein, The Shaker Experience in America: A History of the United Society of Believers (New Haven, Conn., 1992). The early relationship between the Shaker east and west is addressed in “‘Our Spiritual Ancestors’: Alonzo Hollister’s Record of Shaker “Pioneers” in the West,” Communal Societies 31:2 (November 2011): 45-60. The drama of the west’s first thirty years, along with the role of music in the expansion process, is addressed in Carol Medlicott, Issachar Bates: A Shaker’s Life Journey (University Press of New England, forthcoming 2013).

Edward Deming Andrews was also the first non-Shaker to produce a book-length survey of Shaker music, The Gift to be Simple: Songs, Dances, and Rituals of the American Shakers (New York, 1940). Two major surveys followed in the 1970s, including Daniel W. Patterson’s impressive and indispensable The Shaker Spiritual (Princeton, N.J., 1979); and Harold E. Cook, Shaker Music: A Manifestation of American Folk Culture (Lewisburg, Penn., 1973). More recently, scholars of Shaker music have focused on specific genres, hymn books, or settings within the Shaker world. Christian Goodwillie and Jane Crosthwaite present the story of the Shakers’ production of their first hymnal Millennial Praises, and—significantly—restore the majority of its tunes, in Millennial Praises: A Shaker Hymnal (Amherst, Mass., 2009). Carol Medlicott and Christian Goodwillie, in Richard McNemar, Music, and the Western Shaker Communities: Branches of One Living Tree (Kent, Ohio, 2013), execute a similar project for the Shakers’ “western” hymnal of 1833, reconstructing over 100 original tunes and analyzing the hymnal as a window into the history of the west’s first thirty years. Essays in that book also explore the evolution of Shaker hymnody and music notation more generally, and trace the Shakers’ involvement in a printing enterprise. The importance of the hymn genre as a binding element in Shaker culture across the nineteenth century is explored by Carol Medlicott in ‘Partake a Little Morsel’: Popular Shaker Hymns of the Nineteenth Century (Clinton, New York, 2010), who examines evidence for a set of hymns relatively unknown to Shaker scholars that in fact may have dominated worship across much of the nineteenth century. Carol Medlicott offers a series of fresh arguments about the specific innovative aspects of Shaker music in “Innovations in Music and Song,” in Inspired Innovations: A Celebration of Shaker Ingenuity, by M. Stephen Miller (Lebanon, N.H., 2010): 199-206.

There are many significant collections of Shaker primary sources, some of which include vast numbers of music manuscripts. Western Reserve Historical Society alone possesses over 500 Shaker music manuscripts. The Library of Congress is also an important source for Shaker music manuscripts, including an exquisite early hymn compilation by Paulina Bryant of Pleasant Hill, “Record of Ancient songs” (Item 361, Shaker Manuscript Collection). The Library of Congress also houses in its music collection the 600-page manuscript volume assembled by Connecticut Shaker Russel Haskell in 1845, “A Record of Spiritual Songs … in Twelve Parts” (Music Division, 2131/.S4E5). In it, Haskell explains the origin of the hymn genre around 1805 and how it was a marked departure from earlier Shaker songs that were mostly wordless.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.2 (Winter, 2013).

Carol Medlicott is a cultural and historical geographer at Northern Kentucky University. Her work considers various aspects of the western Shaker experience and of early Shaker expansion more broadly. Her publications on the Shaker west include Richard McNemar and the Music of the Shaker West: Branches of One Living Tree (co-authored with Christian Goodwillie, Kent State University Press, 2013) and Issachar Bates: A Shaker’s Journey (University Press of New England, 2013).