To witness the decline of the Enlightenment in American culture, one could do worse than to begin by examining the case of Jane C. Rider, the “Springfield Somnambulist.” The Enlightenment, of course, was a set of scientific, philosophical, and political attitudes circling around the idea that all natural phenomena could be explained in secular, mechanistic terms. Most prominent, and problematic, of these phenomena were those associated with “human nature”–from man’s political strivings to monstrous births, from human disease to the color of one’s skin–all of which were governed by natural forces that were discernable by a careful eye and explicable by a rational mind. Even apparently supernatural or irrational states such as hallucinations, religious visions, trances, outbreaks of insanity, and dreams could be traced to such operations as the circulation of blood through the organs and into the brain, a circulation that might be impeded by poor diet, physical trauma, or unnatural practices. In 1812, Benjamin Rush, the dominant American medical figure of the Enlightenment (and a signer of the Declaration of Independence), described somnambulism, or sleep walking, as “a transient paroxysm” of the brain, “accompanied with muscular action, with incoherent, or coherent conduct.” Rush recommended bleeding, gentle purges, low diet, exercise or labor, avoiding “exciting causes,” and perhaps a “draught of porter, a glass of wine, or a dose of opium” as remedies.

In the spring of 1833, Rider, a well-liked servant of a reputable family in Springfield, Massachusetts, began to act very oddly in the night. This nineteen-year-old daughter of “a respectable mechanic” first experienced intense, intermittent headaches, especially on the left side of her cranium; she slept more than usual; and she reported feeling highly sensitive to the light. Eventually, she began to rise from her bed while still asleep. On some occasions, the Springfield Republican reported, she seemed to perform a somnambulistic parody of her normal work routine, as when “she has got up and set the table for breakfast, with as much regularity as she does when awake, selecting the right articles, and placing them upon the table exactly as they should be.” But more often something was slightly askew: “She frequently goes to the drawers where her clothes are kept, changes the position of the articles, or takes them out, and in some cases has placed some of them where she could not find them when awake.” Some of her behaviors bordered on the marvelous. One night, an eyewitness reported, she threaded a needle twice, sewed a piece of fabric to make a bag for boiling squash, then searched the house for a squash and, not finding one, threw in a piece of meat, and placed the bag in a pot of water over the fire. All of this she accomplished with her eyes closed, and “in a place where there was not sufficient light” to see what she was doing. Other actions seemed at first more mundane: often, she just sat up in bed talking to herself, reciting poetry, praying, or singing. Even here, though, something strange was going on, for when she awoke Miss Rider generally could not repeat the same tunes or lines–most of which seemed to have been learned in her early childhood.

Many in the town of Springfield, as elsewhere during this period of religious revival, took such cases as evidence of a heightened spiritual awareness. In the weeks before the Springfield Somnambulist’s case was reported in the local papers, the Republican ran an account of a “sleeping preacher,” an adolescent girl from New Haven who would arise in her sleep to preach the gospel. When word spread about this miracle, locals flocked to her home, and “the fervor of her praying brought forth a kind of simultaneous panting from all around her.” But in the case of Jane C. Rider, her employers sought a medical cure rather than an exploitation of spiritual prowess, and so they summoned Lemuel Belden, a local doctor with an interest in mental functioning. A graduate of Yale College and a firm believer that all mental processes could be explained by physiological rather than paranormal processes, Belden sought both to banish her troubling symptoms–which must have been increasingly vexing to her employers–and to explain her case to the wider public. In order to do this, he had to pierce the spiritual fog surrounding somnambulism, a fog that was traceable, in large part, to the practices of Franz Anton Mesmer and the “animal magnetizers” of Europe.

In February of 1778, Mesmer announced in Paris his discovery of an invisible “superfine fluid” that surrounded and penetrated all bodies, connecting them in a magnetic chain that, when properly accessed and controlled, served as the key to healing all disease. Mesmer was adept at putting his patients into epileptic-like fits or somnambulistic trances, in which state he would run his hands over the patient’s body, seeking the magnetic poles that controlled the flow of fluid. Sometimes he put groups of his convulsives in special tubs containing “mesmerized” water, in which the patients would transmit the invisible fluid to one another with the aid of special iron rods and ropes linked to their thumbs. At other times he sent them outdoors to form human daisy chains around mesmerized trees; or, alternatively, he brought his patients indoors where their mesmeric flow would be harmonized to the sounds of special mesmeric music wafting from a glass harmonica (the master conducting the proceedings in a lilac taffeta robe). When his subjects were in such states, Mesmer claimed that he could restore the equilibrium of the body’s supply of animal magnetism and cure all ills.

Mesmer’s combination of showmanship and mysticism combined with what today seems an outrageous appeal to the language of Enlightenment to make his new “science” one of the most hotly debated topics of pre-Revolutionary France; it eventually spread across the continent, and indeed across the ocean. As the historian Robert Darnton explains it, part of Mesmerism’s initial appeal was that it promised a rational explanation for illness that strongly resembled the period’s other astounding discoveries. If the public could accept the presence of electricity running through lightning rods, gravity holding one down to the ground, and helium lifting one off of it, then why not believe that an unseen fluid harmonized the individual body with all of nature? And given the sorry record of “legitimate” European medicine in the period, a profession that one historian of medicine recently noted was as likely to kill a patient as to cure her, it is no surprise that Mesmerism–which at least did no damage–successfully passed itself off as the cutting edge of Enlightenment science. By the time Lemuel Belden took on the case of Jane C. Rider, the concept of somnambulism was thoroughly entwined with mesmeric theories and practices. But mesmerism itself had undergone significant changes in the intervening years. Mesmer’s followers, most notably the Marquis de Puységur, advanced the notion that “artificial somnambulism” (as the mesmeric trance was often called) was a purely spiritual state induced only by the power of a properly trained “operator” over a (usually female) subject. Mesmeric or magnetic fluid, they believed, was still a material–if intangible–substance, but mesmerists increasingly spoke of it as an aspect of divinity itself, something that resisted the mechanistic explanations of the Enlightenment. And the mesmeric subjects, in addition to being healed, were increasingly thought to be gifted with clairvoyance, extrasensory perception, and mind-reading capabilities.

To this point, there were occasional outbreaks of American enthusiasm for mesmerism, but it was known mostly through casual discussions of European fads in journals. The mesmerists’ attempts to bring their new science to the new world had been dealt a series of grievous blows as far back as 1784, when Benjamin Franklin participated in a royal French commission that pronounced Mesmer a fraud. Not long afterward, the Marquis de Lafayettte tried to interest George Washington in artificial somnambulism, leading an appalled Thomas Jefferson to circulate copies of the French commission’s report. These pillars of the American Enlightenment, then, had little taste for the more arcane psychic investigations of some of their European counterparts.

And yet “natural somnambulism” manifestly existed, and along with it came strange powers that even Benjamin Rush could not ignore. We often read, he wrote, “of the scholar resuming his studies, the poet his pen, and the artisan his labours, while under [somnambulism’s] influence, with their usual industry, taste and correctness.” Lemuel Belden was most fascinated with Rider’s visual prowess. While she was somnambulating with closed eyes, she could read “a great variety of cards written and presented to her by different individuals” and “told time by watches.” Investigating further, he found that with wadded up cloths in her eye sockets and two thick blindfolds around her head, she could still read the cards and even write, dotting the I’s in the correct places. She also had an increased receptivity to musical tones and to certain memories. But in her trance state she mistook her father for a little boy in the village and in general did not notice or properly recognize her surroundings.

It is not clear whether crowds started flocking to see Rider perform her extraordinary feats before or after Belden took the case and began to publicize it. One might suspect him of charlatanism–he would not have been the first and certainly not the last to exhibit a somnambulist for financial gain or popular attention. And one might suspect that Jane C. Rider herself had some conscious role to play in putting on a show: as word spread of her deeds, she conveniently began to “fall asleep” more often in the daytime; and villagers seemed to have an uncanny sense of when these fits would occur–indeed few if any came away dissatisfied. The servant may well have found, and enjoyed, a ticket to fame by shamming and embellishing some of her strange sleep habits; the doctor, wittingly or not, began to assume a role not unlike a carnival barker, as he put her through various public tests. But what happened next in the career of the Springfield Somnambulist suggests that her condition was not entirely a put-on.

In order to shield Rider from the strain of a “constant succession of visitors” and provide her with the “seclusion which seemed essential to her cure,” Belden had her removed in November 1833 to the State Lunatic Hospital at Worcester. The first state-run asylum erected on “modern” principles, the Worcester hospital had opened in January of that year. At first this seems an odd choice. By the time Rider was admitted, there were approximately 164 inmates at the asylum, more than half of whom had been sent from jails, almshouses, and houses of correction. Many of them were violent, and eight of the first forty had been convicted of murder. In fact, as Gerald Grob has shown in his study of the Worcester hospital, jail keepers were often motivated to send insane convicts to the asylum, not to protect them from ordinary criminals, but to protect the ordinary criminals from the “furiously mad.” The early history of the Worcester asylum seems to confirm for American asylums French historian Michel Foucault’s influential thesis that the European asylum movement–for all its humanitarian rhetoric–was little more than a mechanism for the thorough segregation of the insane from bourgeois society. And yet the humanitarian rhetoric of the asylum was no mere fig leaf for segregation. The first wave of public asylum superintendents justified massive expenditures from the legislature and their own novel powers to rescind the liberties of mentally afflicted citizens by pointing to extraordinary cure rates resulting from their system of treatment, which consisted of careful attention to both the medical and environmental conditions of the insane. The “moral treatment,” as it was known, was shown to cure the great majority of all cases of insanity, even the most violent among them. Some estimates (later disproved) put the cure rate at over 90 percent, and in the more successful asylums over half the admitted patients were discharged as cured within a year.

Into this unlikely environment walked–perhaps while sleeping–the young Jane C. Rider. One can speculate on several reasons for her admission. First is that as a serving girl she was becoming increasingly inconvenient to her employers. Why should they continue to support her when her sleeping self undid all the work that her waking self was charged with performing? And what about all the gawkers showing up to witness the strange theater performed by their domestic? The asylum offered a humane way for the family to get the troublesome servant off their hands, and at public expense. Asylum treatment was far better, for the image of the family, than to abandon her to an almshouse. Second, Belden himself saw an opportunity to expand his solitary observations within the emerging science of psychiatry. (The name had not yet been invented, but most historians date the origins of the psychiatric profession to the emergence of what was then usually called “asylum medicine.”) The superintendent of the asylum, Samuel Woodward, had been one of Belden’s mentors, and even had examined Belden on his matriculation from Yale (according to the Woodward family papers at the American Antiquarian Society). This case offered Belden a chance to bolster his professional ties to an eminent man of science. And finally, for Woodward, Rider was already a notorious case; if he could devise a cure, it would be another feather in his cap. And it was surely a relief to be offered such a fascinating specimen who was neither a furious maniac nor a convicted murderer.

As Belden and Woodward tackled the case, they cast themselves in the familiar scientific role of champions of the Enlightenment dispelling the darkness of mysticism and ignorance. There was absolutely no doubt for either man that Rider’s case depended, as Woodward wrote, “on physical disease,” and that it would “gradually disappear, if a judicious course be pursued.” Praising the initial investigations of his younger trainee, Woodward–acclaimed as one of the leading medical minds of New England–wrote that his and Belden’s views on the causes and treatment “perfectly coincide.” But despite Belden’s training at Yale and Woodward’s status as an examiner there, Woodward’s mentoring of Belden was in some ways a case of the blind leading the blind. Woodward himself had not attended medical school and knew little about the newer approaches to medicine in general and to the study of insanity in particular that were being fashioned in Europe.

And contrary to the united front they presented in the final write-up of the case, we can see in their course of action at least two theories of the disease operating simultaneously, with crude attempts to join them together. Belden seemed convinced at the outset that the seat of Rider’s troubles was her digestive tract. Before she was admitted to the asylum, he started her on a course of emetics (to induce vomiting); while this did not cure her, he and Woodward experimented with her diet throughout her stay in Worcester. For his part, Woodward decided early on that Rider’s case could be explained by the principles of phrenology, the fashionable science of skull shape as an indication of character, in which he was growing increasingly interested: at this time he was writing letters to the great scientist of brain bumps George Combe, begging him to visit Worcester. The soreness in Rider’s head, Woodward believed, indicated that one of the brain’s regions or “faculties” was overexcited or distended, causing not only pain but enhanced sensory perceptions during her trances.

Both men, though, rejected the mesmeric twaddle that passed for so much scientific thinking regarding somnambulism in Europe. The extraordinary feats of night vision that had made for such good theater in Springfield could not be explained by the dubious workings of “animal magnetism,” which was said to have caused people to discover “the contents of a sealed letter by merely applying it to the pit of the stomach or the back of the head, or what is stranger still, [to detect] the secret thoughts of another only by contact, or without contact, if placed in a certain magnetic relation.” No, Rider’s case would only “admit of a solution on less questionable principles.” When she read those cards with her eyes closed, her sockets filled with rags, and a blindfold tied around her head, “she actually saw.” A tiny amount of light must have penetrated the bindings, which was enough for her retina, with its “increased sensitivity,” to record a sense impression; and “a high degree of excitement in the brain itself [enabled] the mind to perceive even a confused image of the object.”

But how to “cure” such a case? As with so much early-nineteenth-century medicine, the answer was essentially to try everything until something worked. Rider herself had been taking laudanum and ether before bed to help ward off the fits, and, as Belden wrote in an article for the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, “this she was permitted to continue” until it was established that the drugs were ineffective. In order to “subdue that irritability of the brain which formed the basis of the disease,” she was bled copiously, and then had her feet put in a warm bath with mustard flour. Her head was shaved and her scalp “blistered,” or cauterized. She was given a laxative and told to exercise, and her diet was strictly monitored. But the paroxysms continued, and so she was treated to a virtual pharmacy full of drugs, whose names conjure up a repertoire of discarded medical techniques: a nitro-muriatic bath, tincture of stramonium, guaicum, carbonate of iron with extract of conium, emetic of ipecac, sulphate of zinc, calomel, opium, sanguinaria, the liquor potassae arsenitis, purssiate of iron, sulphate of quinine, and nitrite of silver. There is no detailed record of how Rider responded to these interventions, but Belden does tell us that “some medicines… were almost invariably followed by a paroxysm.” One can indeed imagine that a helping of opium followed by the powerful sedative conium might very well bring on something resembling a somnambulistic fit. During one of these paroxysms, Rider cried out, “My head, my head, do cut it open!” Whether this is better explained by phrenological principles or by the massive intake of drugs is an open question.

Jane C. Rider’s trances never entirely vanished, but after a few months in the asylum, wrote Woodward, “she has never appeared so cheerful, and in so good spirits.” She even demonstrated that she could return to her proper station in life, as a servant: “In the absence of one of our attendants . . . she has done more or less work in the halls every day.” There is a creepy geniality to some of Woodward’s notes about his researches at this point, which one senses the patient bore rather stoically, with a smile plastered to her face. “During the last paroxysm I applied leeches to her head. She waked during the paroxysm, not a little surprised at her new head ornaments.” Rider wrote a few letters to Belden, expressing her thanks to her doctors and her assurance that her condition was coming increasingly under control. She hoped soon to be released–”not that I am discontented in the least, for I am not. The time has passed very quick and pleasantly. I take a ride almost every day–that I like very much, and think it does me good.” Woodward, of course, had read this letter before it was sent and added his own postscript to it. Rider knew what her doctors wanted to hear and told it to them. It was this, as much as any improvement in her condition, that appears to have occasioned her release one month later; even Woodward admitted that she still had the occasional sleepwalking fit.

The fact that Jane C. Rider never entirely gave up sleepwalking throughout this ordeal should convince us of the reality of her condition, no matter how theatrical it first appeared. And yet at the end of her tenure at the State Lunatic Hospital, her doctors had no real explanation for her condition, other than a vague confirmation of their initial hypotheses. The episodes seemed to be brought on by “the free use of fruit,” particularly green currants, which Woodward suspected that Rider was smuggling into the asylum despite his strict orders. An irregular menstrual flow may also have been an “exciting” (or precipitating) cause; but the doctors, perhaps out of a sense of decorum, said little about their investigations into this matter. Yet at the core, a fundamental mystery remained. As Belden concluded: “If it be asked how a physical cause, acting either directly or indirectly on the brain, can . . . endow [the brain] with the power of perceiving relations to which it had before been insensible, I can only answer, I do not know . . . [W]e here reach a gulf which human intelligence cannot pass.” Woodward was ultimately awed by the extraordinary snatches of memory that Rider’s sleeping self exhibited. This seemed evidence not only of certain overexcited faculties of the brain, but of the fact that “all knowledge once impressed on the mind, remains indelibly fixed there, and only requires a strong stimulus to call it forth.” For Woodward, the marvelous workings of Rider’s brain seemed to augur “a future state of existence” in which “all the knowledge which we gain in this world will, by the increased energy of mind, be restored to the recollection, and be at the command of the will.” Echoing Belden’s sense of the impassable limit of human understanding, he chalked up this astonishing vision to the only god the Enlightenment ever knew, “the grand designs of the Almighty Intelligence.”

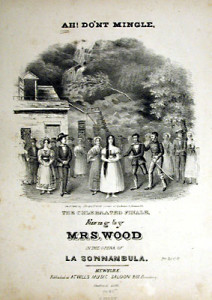

Of the Springfield Somnambulist we know little after her “quick and pleasant” stay at the insane asylum. A magazine piece that revisited Rider’s case twelve years later reported that she was “cured” by Woodward and Belden’s treatment and that since then, there had been “no return of the affection.” But if Jane C. Rider slipped into obscurity, by the end of the decade–and throughout much of the century–the American cultural landscape would be full of sleepwalking young women. Reading while blindfolded, responding to the unspoken will of their operators, peering into the minds of audience members, diagnosing their own and others’ medical conditions, and foretelling future events, they somnambulated across stages in lyceums, museums, theater halls, and amusement parlors nationwide. This happened because, despite the best efforts of men of science like Woodward and Belden, mesmerism finally took hold in America after 1836, when Charles Poyen spread the gospel according to Mesmer, and especially Puységur, on a triumphant New England tour. At least seven mesmeric journals were soon founded; numerous scientific and religious books exploring the secrets of sleep, dreams, trance states, and animal magnetism were published; serious writers like Poe and Hawthorne mined the dramatic and philosophical potential of artificial somnambulism; antimesmeric works like Confessions of a Magnetiser (1845) abounded; and mesmeric scenarios were enacted on the minstrel stage and in melodramas. Not surprisingly, the Bellini opera La Sonnambule became one of the most popular musical productions of the period, with such luminaries as Mrs. Wood (Mary Anne Patton) and Jenny Lind thrilling audiences with their renditions of the title role (see figs.).

The historian Robert C. Fuller has written that mesmerism captured the American popular imagination when it ceased to be a “system of medical healing” and became a full-blown spiritual phenomenon that promised the triumph of mind over matter. In the age of Jacksonian democracy, evangelical Protestantism, and Manifest Destiny, mesmerism complemented the American faith in the power of the individual to conquer material circumstances through heroic acts of will. In an essay that was widely reprinted in the U.S., Poyen wrote that “magnetical sleep” was that aspect of human activity that mirrored the “infinite power” of the “divine spirit.” Although he still couched his discussion of somnambulism in physiological terms, describing it as “a peculiar state of the brain and the nervous system,” the mystical power this state unleashed in the individual could only be fully accessed and manipulated by a new kind of priesthood, the tribe of “magnetizers.” As such, American mesmerism marks a point at which Enlightenment thinking slides over into romanticism, with its refusal to grant to rationality the power to unlock all the secrets of nature, and with its fascination with the spiritual powers of the unmoored individual.

If the moment of mesmeric ascent signals the decline of the Enlightenment in American culture, it also marks the site of an ongoing battle between that self-proclaimed bastion of Enlightenment thinking–the asylum–and key developments in American social and cultural life. Many of the same forces that mesmerists claimed could be put to therapeutic use were considered by asylum superintendents to be extraordinary threats to mental health. The orphic pronouncements, the claims to supernatural control over one’s body, and even excessive enthusiasm for new doctrines–all these were treated as symptoms of a mind diseased, rather than as gateways to universal health. This is because for all its novelty, the asylum was at core a paternalistic and socially conservative institution. Asylum superintendents considered settled, traditional practices and ways of life the most healthy, and they believed that the modern emphasis in literature, religion, and politics on the powers of the individual to remake him or herself left solitary individuals at risk to pursue dangerous impulses and follow frightening new doctrines. Mesmerism, too, threatened the authority of the new psychiatric profession by promising a quick, universal solution to imbalances between the mind and the body, precisely the problem that asylum superintendents were proposing to solve in their own institutions. It is not surprising then, that as mesmerism gained influence in American popular culture, so too did it regularly find its way onto the list of “exciting causes” of insanity in the annual reports of American insane asylums.

The story of Jane C. Rider can be read as an episode in the clash between rival systems of mind cure. The asylum movement that “cured” her carried the torch of Enlightenment thinking (humans have power over nature only through the secular exercise of rationality); the mesmerists who ultimately cornered the market in somnambulism and related trance states embodied a popular mystical romanticism (humans have power over nature through their recognition of and manipulation of the divine spark within them). But this is only a partial explanation, for no categories so broad as the Enlightenment and romanticism can explain the fumbling attempts of the doctors, the journalists, the townspeople, the employers, and Jane C. Rider herself to understand what was for all of them a wondrous and horrifying condition. And so we are left at the end with little totems of historical curiosity and pathos: the cloths wadded up in Jane C. Rider’s eyes, those little green currants that were considered to be the source of her woes, and her agonized cries of “My head, my head, do cut it open!”

Further Reading:

Jane C. Rider’s story is taken largely from L. W. Belden, The Case of Jane C. Rider, the Somnambulist (Springfield, Mass., 1834), which also contains selected case notes from Samuel Woodward. Thanks to Patricia Cline Cohen for pointing me to this fascinating little booklet. A useful interpretive frame for the history of mesmerism–as well as the source of my subtitle–is Robert Darnton, Mesmerism and the End of Enlightenment in France (Cambridge, Mass., 1968). On the American history of mesmerism, see Robert C. Fuller, Mesmerism and the American Cure of Souls (Philadelphia, 1982). No study of nineteenth-century insane asylums would be complete without consideration of Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (New York, 1979); but one must not take all of his sweeping (though generally brilliant) arguments for granted. A more careful–though less critical–study of the American asylum movement is Gerald N. Grob, Mental Institutions in America: Social Policy to 1875 (New York, 1973). Grob’s work on the Massachusetts State Lunatic Hospital and the career of Samuel Woodward has also been helpful here; see his The State and the Mentally Ill: A History of Worcester State Hospital in Massachusetts (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1963). An indispensable study of insane asylums within the broad contexts of nineteenth-century politics and society is David J. Rothman, The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic (Boston, 1971). A highly readable and beautifully illustrated overview of ideas about madness in America is Lynn Gamwell and Nancy Tomes, Madness in America: Cultural and Medical Perceptions of Mental Illness before 1914 (Ithaca, 1995). I wish to acknowledge the excellent research assistance of Jessica Mitchell in preparing this article.

This article originally appeared in issue 4.2 (January, 2004).

Benjamin Reiss is assistant professor of English at Tulane University. He is the author of The Showman and the Slave: Race, Death, and Memory in Barnum’s America (Cambridge, Mass., 2001). He is currently at work on a cultural and literary history of nineteenth-century American insane asylums.