Or, the feeling Philip Vickers Fithian

Can Presbyterians fall in love? Okay, everyone falls in love, but when people think of Presbyterians they normally conjure up images of stoic Protestants whose kids eat oatmeal and memorize the Westminster Confession of Faith. Reverend Maclean, the Montana minister and father figure played by Tom Skerritt in A River Runs Through It, comes to mind. Presbyterians don’t “fall” in love—they rationally, and with good sense, ease themselves into it.

This was my image of Presbyterians until I read the correspondence of Philip Vickers Fithian. Most early American historians know Philip Vickers Fithian. He was the uptight young Presbyterian who served a year (1773-1774) as a tutor at Nomini Hall, the Virginia plantation of Robert Carter, and wrote a magnificently detailed diary about his experience. For most of us, Fithian is valued for his skills as an observer. His journal offers one of our best glimpses into plantation life in the Old Dominion on the eve of the American Revolution.

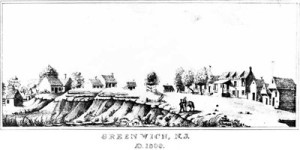

But despite Fithian’s ubiquitous presence in the indexes and footnotes of contemporary works of Virginia scholarship, most of us know little more about him than the very barest facts: He was born in 1747 in the southern New Jersey town of Greenwich. He was the eldest son of Presbyterian farmers but left the agricultural life in 1770 to attend the College of New Jersey at Princeton. After college he worked for a year on Carter’s plantation and was ordained to the Presbyterian ministry. In 1776 he headed off to New York to serve as a chaplain with a New Jersey militia unit in the American War for Independence.

Such chronicling—the stuff of encyclopedia entries and biographical dictionaries—only scratches the surface of Philip’s life. It fails to acknowledge the inner man, the prolific writer who used words—letters and diary entries mostly—to make peace with the ideas that warred for his soul. Philip was a man of passion raised in a Presbyterian world of order. He came of age at a time when Presbyterians were rejecting the pious enthusiasm of the Great Awakening for a common-sense view of Christianity. And while Philip was clearly a student of this newer rational and moderate Protestantism, he remained unquestionably Presbyterian. For he was a man stretched between worlds: one of cautious belief, another of passion and sentiment; one of rational learning, another of devotion and deep emotion. His struggle to bring these worlds together is seen most clearly not in his well-known observations of plantation life but in his letters to the woman he loved—Elizabeth Beatty.

Philip first met Elizabeth “Betsy” Beatty in the spring of 1770 when she visited the southern New Jersey town of Deerfield to attend her sister Mary’s wedding to Enoch Green, the local Presbyterian minister. It may not have been love at first site, but it was close. Philip was enrolled in Green’s preparatory academy, and Betsy was the daughter of Charles Beatty, the minister of the Presbyterian church of Neshaminy, Pennsylvania, and one of the colonies’ most respected clergymen.

Betsy was a new face in Deerfield, a fact that made her especially enchanting to the town’s young men. Philip had spent enough time with Betsy while she was visiting to begin a friendly correspondence with her. In his first letter, written shortly after she returned to Neshaminy, Philip wrote, “You can scarcely conceive . . . how melancholy, Spiritless, & forsaken you left Several when you left Deerfield!” He hoped for a prominent place “in this gloomy Row of the disappointed.” Since Betsy had departed Deerfield he could not “walk nor read, nor talk, nor ride, nor sleep, nor live, with any Stomach!” The “transient golden Minutes” they had spent together, he added, “only fully persuaded me how much real Happiness may be had in your Society.” Philip was smitten.

Betsy did not reply to this letter, and Philip’s obsession waned as he headed off to college in the fall of 1770. While he was there Philip had more than one opportunity to see Betsy again. He joined fellow classmates on weekend excursions to visit Charles Beatty’s church at Neshaminy, and it was during these visits that he made his first serious attempts to court Betsy. Though Philip and Betsy would spend much time together over the course of the next several years, the establishment of a correspondence was equally important to the development of their relationship. Betsy had given Philip permission to write her, a clear sign that she approved of his desire to move the friendship forward. By February 1772 he was signing his letters with the name “Philander” (“loving Friend”), an obvious indicator of his affection for his new correspondent.

Though much of Philip and Betsy’s courtship was conducted through letters, the exchange of sentiments usually flowed in only one direction. Perhaps Betsy did not like to write. Perhaps she preferred more intimate encounters or feared the lack of privacy inherent in letter writing. Or perhaps she did not want to encourage her suitor with a reply. Whatever the case, women generally did not write as much as men, especially when it came to love and courtship letters. In other words, Betsy may simply have been following the conventions of her day.

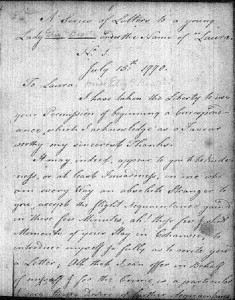

By summer 1772 Philip’s visits to Neshaminy became more frequent and his letters became more sentimental. He now began to address Betsy as “Laura” (a probable reference to Petrarch’s devotion to Laura), a name of affection that he would use for the rest of his life, and he now felt comfortable sharing the daydreams that distracted him from his studies at Princeton. “I lead you by the Hand in a cool bright Evening, & once more, in that lovely garden oh! in that pleasant, pleasant Garden, hold Conversation in Rapture with you!

One of the many turning points in the relationship occurred following the death of Betsy’s father in September 1772. Charles Beatty had died prematurely during a fund-raising visit to Barbados on behalf of the College of New Jersey. Philip’s sympathy for Betsy was authentic. He had lost his parents seven months earlier to an unknown disease, and now Betsy’s mourning excited in him “a fresh & feeling sense of the same Pain, which had not yet Subsided, when on a sudden it was renewed & increased by Sympathy with you.” Using Calvinist language that would have been consoling to the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, Philip tried to comfort Betsy. “It hath pleasured Heaven, whose work we ought to view & reverence, to make you & I & our families orphans! The ways of Providence are indeed mysterious & the Design is to us unknown.” He connected on a deep level with Betsy during this season of sorrow. Her mother had died in 1768 when she was a teenager, and now she, like Philip, was without parents. This shared experience brought the couple closer together. Ten days later, while she visited Philip at Princeton’s graduation, Betsy gave him, in his words, “an expressive & visible Token, or Pledge, of . . . real Friendship.” Though the nature of the pledge is unclear, Philip was pleased by it.

Things seemed to be going well between Philip and Betsy as the summer of 1772 gave way to autumn. Betsy continued to make regular trips to Deerfield to visit her sister, and Philip, who had recently completed his studies at the College of New Jersey and had moved back home, embarked on the occasional visit to Princeton to see friends. There would, in other words, be ample opportunity to sustain the courtship. However, somewhere along the way things went terribly wrong. Philip, it appears, mistook Betsy’s September 1772 pledge of friendship for something much more. In the months after his college graduation he began to come on strong—a bit too strong for Betsy. His letters were now full of romantic gestures and flowery disclosures of his sentiments. In December, while visiting Princeton, Philip proposed marriage (Betsy was in Deerfield at the time) in a passion-filled letter that he would later describe as a “wild and incoherent epistle.” He told Betsy that he would be back in Deerfield the following day and encouraged her to “consult with your own Heart” so that they could discuss his offer. He would then ask her for “a full and conclusive Answer.”

Philip was making demands, but he knew Betsy was the one in control. We do not know the details of what happened on December 3, 1772, but the Deerfield meeting did not go well for Philip. Betsy rejected his proposal. Twelve days later he sounded like a man who had been scorned. He sent Betsy a long poem, which included the lines, “Why does my Heart these raging Tortures feel/Whose Force I cannot from the World conceal?” Philip was left to pick up the pieces.

By the end of the month the gossip mill was churning in this rural world of Greenwich and Deerfield, and Philip thought he now understood the reason for Betsy’s decision. According to what Philip had heard, Betsy did not take his proposal seriously because of his reputation for gallantry. Betsy had heard a rumor that she was not the first or only woman to whom Philip had proposed marriage. We cannot be sure if this accusation was true, but in Philip’s defense, there is no evidence of a marriage proposal to another woman in any of his extant writings. He seems to have been justified when he wrote to defend himself and his reputation. On the other hand, Philip was no stranger to the company of young Presbyterian ladies. He had been accused of gallantry before and would be accused of it again. Yet, he insisted that his proposal to Betsy “was the first & only one, of the like Nature that I ever made.” Somewhere along the way Betsy had received some false information.

The rumors were nonetheless terribly embarrassing for a Presbyterian gentleman who was expected to be above such small capitulations to passion. Philip realized that his reputation would only be salvaged once he ended his relationship with Betsy. He thus announced his intention to “renounce, abjure & annul every Tie, Band, Engagement, or Penalty” between them. This young Presbyterian had learned a valuable lesson. His affections had been too strong and irrational. As one of his Princeton teachers, the theologian and moral philosopher John Witherspoon, had taught, enlightened men were, above all else, rational beings. If a society were to be virtuous and refined, the passions had to be regulated. Failures of self-control reflected failures of reason, and for most Presbyterians of Philip’s generation, failures of reason were also moral failures.

Of course love conquers all, so they say, including arch reason. And Philip could not forget Betsy—even if he had wanted to. She continued to appear in Deerfield, and Philip, who was then living and studying with Green in preparation for his Presbyterian ministerial licensing exam, could not help but see her. Not surprisingly he found Betsy acting “cold” and “indifferent.” Unable to bear the awkward meetings, he decided to resort to the pen once again.

In his first letter in three months, Philip confessed that his marriage proposal of the previous December had been poorly timed and was the result of “over-anxious Desire,” but he admitted that Betsy’s current indifference toward him was stirring his passions into a “strange Commotion.” Philip remained persistent, refusing to take Betsy’s coldness as a sign of rejection. Still, a feeling of desperation overcame him, and he ended up pleading with Betsy to take him back, telling her that he was “in the fullest sense” her “Slave.”

Philip continued with the letters and poetry but to no avail. He pulled out all the stops to get his “dear Laura” back, writing, “Why does my silly Bosom rise/And vent its grief with fruitless sighs?/Shall I sit whining over my pain/And die for one I can’t obtain?/Have I been kept so long at School/To die of Love, as dies the Fool . . . ” This kind of romantic poetry exposes the tensions Philip was feeling. His schooling at Princeton had taught him to guard his passions, but his love for Betsy seemed uncontrollable.

By late spring 1773 Betsy had returned to Pennsylvania, and Philip had immersed himself in his studies. He did not write to her again until August. The occasion for renewing his correspondence was a trip he had made to Princeton to discuss a job opportunity on Carter’s Virginia plantation. During his stay he took a familiar ride into the country to see Betsy’s brothers in Neshaminy. Betsy was also there, and Philip had the occasion to drink tea with her and engage in “some fine Conversation.” Days later Philip wrote to her about the momentous decision he had before him regarding his tutoring opportunity in Virginia. Though Philip would remain with the Carters for only one year, at this stage the ultimate length of his stay was uncertain. In the event that the move would be permanent, he would have to know where he stood with Betsy. How would she respond to his decision to go to Virginia—a place far removed from the Presbyterian orbit in which she traveled?

Judging from Philip’s behavior over the coming months, her response was as he would have wanted, but in a fashion typical of dueling lovers, Philip nonetheless chose to leave for Virginia. Even with Betsy’s renewed affection, the two could not commit to each other. After arriving in Virginia, Philip wrote that had Betsy been “less uncertain of her future Purpose” he would never have left Deerfield.

Philip corresponded with many of his friends during his stay in Virginia, but no one received more letters than Betsy. His epistles from Virginia were not overly passionate, but we know that privately he continued to find it difficult to exercise restraint. “In Spite of all my strongest opposing efforts,” he wrote, “my thoughts dwell on that Vixen Laura. I strive to refuse them admission, or harbour them in my heart, yet like hidden fire they introduce themselves, & seize, & overcome me when perhaps I am pursuing some amusing or useful Study.” Though he was enjoying his time with the Carter family and learning a great deal about Virginia, he could not help “reflecting on my situation last winter, which was near the lovely Laura for whom I cannot but have the truest, and warmest esteem possible! If Heaven shall preserve my life, in some future time, I may again enjoy her good society.”

During his stay with the Carters, Philip had multiple opportunities to meet and court the daughters of some of Virginia’s most prominent planters. Matchmaking was a popular social practice in plantation Virginia, and the Carters were constantly trying to find their new tutor a suitable marriage partner in the hopes that he would take up permanent residence in the Northern Neck. Philip delighted in his chance to meet these young ladies, but he also made it clear in both his public declarations and private writings that his heart belonged to Betsy. He remained so devoted to her that the Carter boys, who were notorious for their infatuations with the girls in the neighborhood, wondered whether their tutor ever thought about the opposite sex. “Yes, Harry, & Bob,” Philip responded in his diary, “Fithian is vulnerable by Cupid’s Arrows—I assure you, Boys, he is, Not by the Girls of Westmoreland—O my dear Laura, I would not injure your friendly Spirit; So long as I breathe Heavens vital air I am unconditionally & wholly Yours.”

As Philip became more assured that Betsy was interested in hearing from him, his correspondence grew more florid.

Perhaps it is not coincidental that this change of tone corresponded with changes in Philip’s reading habits. While in Virginia, he had time to digest some of the era’s most popular fiction, particularly that of Laurence Sterne. Philip had started reading Sterne’s Letters from Yorick to Eliza (1773), composed as a series of love letters between Yorick, an Anglican minister (a pseudonym for Sterne), and Eliza Draper, a young married woman with whom Sterne had carried on a three-month affair. The letters are so laden with passion and maudlin sentiment that it is hard not to think—as some modern scholars have—that Sterne was simply parodying the social conventions of his age. Any irony, however, seems to have escaped the Presbyterian Fithian. His letters are exemplars of the form and style caricatured by Sterne. Of course it may have been especially difficult for Philip to detect Sterne’s irony since his plight paralleled so closely that of Yorick. Both were infatuated with women named Eliza; both were ministers; both found themselves living at great distance from the object of their affections; and both faced the daunting obstacle of keeping passion’s fire aflame with nothing more than paper and quill pen.

Further intertwining his life with Sterne’s art, Philip began copying passages from Sterne in his letters, simply replacing the name “Eliza” with that of “Laura.” Sterne toasted Eliza at his elaborate dinner parties, and Philip toasted Betsy before similar events on the Carter plantation. Sterne encouraged Eliza to begin the practice of rereading his letters to her in India and then, when time permitted, to put them in chronological order as a means of remembering him during their period of separation. Philip did not ask Betsy to do the same with his letters (he wondered if she even saved them), nor could Philip sort the correspondence he received from Betsy since he had only, at the most, two letters. What he could do, however, was organize the copies of the letters he had sent. In May 1774 he wrote her what he called a “chronological” letter cataloging the theme of every piece of correspondence he had sent since they first became acquainted four years earlier.

By modeling his correspondence on Sterne’s letters to Eliza, Philip was fashioning himself as a man of feeling. By the second half of the eighteenth century, Enlightenment rationalism was under attack from a culture of sensibility that celebrated a new kind of gentleman. This new man was no longer asked to govern himself by the dictates of reason alone but was invited to express his emotions in public and private, even to his female friends and correspondents. A real gentleman was thus able to communicate his affections for the opposite sex in much the same way that Sterne had done with Eliza and, to some extent, the way Philip was doing in his letters to Betsy. The culture of sensibility offered Philip a language that, unlike the Presbyterian rationalism in which he was raised and educated, did not condemn his passionate side.

As many warned, and as Philip no doubt knew, the culture of sensibility, with its emphasis on feeling and emotion, could turn destructive. Passions detached from an equally strong rational faculty could undermine the rational foundation of social order. While it is understandable that Philip would have found a kindred spirit in Yorick, he thus could not allow himself—as Yorick was in danger of doing—to become enslaved by his passions. The moral philosophers who advocated sentimental behavior as a means of sustaining a virtuous society made sure to stress that such affections needed always to be held in check by reason. The man of feeling was not an emotional enthusiast but instead pursued a “moderated sensibility.” For Philip, this was easier said than done.

Sentimental fiction and the passions it could elicit from readers such as Philip were also dangerous from the perspective of Philip’s religion. Laurence Sterne was not the kind of author Presbyterian ministers normally turned to when they wanted to teach their parishioners about courtship and marriage. John Witherspoon, Philip’s Princeton mentor, believed that writers like Sterne promoted ideas about the opposite sex that were “impossible to gratify.” Such literature relegated the God-given institution of marriage to the “scoffs of the libertines.” Philip’s letters suggest that he never quite forgot Dr. Witherspoon’s lessons. However much he may have identified with Yorick, he never let his passions get the better of him. In this sense, he remained the true Presbyterian.

Joy and tragedy characterized the rest of Philip and Betsy’s Presbyterian love affair. Upon his return from Virginia, Philip was licensed as a Presbyterian minister. The Philadelphia presbytery sent him to the Susquehanna and Shenandoah River valleys as an itinerant missionary to the Scots-Irish settlers in these regions. But before he left he had managed to win Betsy’s heart. Whatever reservations she may have once had about pursuing a relationship with Philip had all but disappeared. As he prepared to head west, he paused for a heartfelt and emotional good-bye with the woman he loved. Betsy wept during the course of their conversation; her tears, Philip wrote, “drowned me in melancholy Rapture.” As she held Philip’s hand, he sat in a “mournful Posture by her Side.”

Philip left for the backcountry with marriage on his mind. He and Betsy had had their share of difficult moments together, but their relationship now appeared to be secure. During a break in his itinerant tour, on October 27, 1775, the couple wed at the Deerfield Presbyterian Church. Whatever kind of honeymoon the newlyweds enjoyed was short lived. Philip needed to finish his missionary tour.

In May 1776, after returning to Greenwich, Philip was assigned to preach before his home congregation, the Greenwich Presbyterian Church. He and Betsy probably settled down in the local farm house in which he had been born and raised. But whatever wedded bliss they shared would not last long, for these were revolutionary times, and Philip, like most Presbyterians of his age, was a patriot.

Only a few weeks into his preaching stint at Greenwich, duty called once again. By mid-July 1776 Philip was serving as a chaplain to a regiment of New Jersey militia stationed in New York City. He would soon find himself in the midst of the Battle of Brooklyn, preaching weekly sermons to the troops and ministering to their physical and spiritual needs. Through it all he kept in close contact with Betsy, reporting on the events of the war, instructing her on business matters, and reaffirming his love for her. After the Battle of Harlem Heights, with Philip’s regiment stationed near Mount Washington, New York, dysentery entered the camp. Philip would become one of its victims. On September 19, he wrote Betsy about his return to Greenwich and his hopes for their renewed life together. He ended the epistle with a prayer: “Peace & God’s Blessing be with my Betsey, my dear Wife, forever may you be happy.” It was the last letter Philip Vickers Fithian would ever write.

This article originally appeared in issue 8.2 (January, 2008).

John Fea teaches American history at Messiah College in Grantham, Pa. He is the author of The Way of Improvement Leads Home: Philip Vickers Fithian and the Rural Enlightenment in Early America (2008).