We seem to have entered an era in which global financial capitalism has become more opaque than ever. Mountains of paper bonds, securities, mortgages, and credit change electronic hands in cyberspace, while hedge-fund managers, portfolio insurers, and international bankers manipulate our investments in shrouds of mystery until their schemes crash. And even then the mystery remains. Regulatory officials and lawmakers fail to keep up with the brokers and managers who hatch ingenious plans for investing billions of dollars. Rising expectations and dashed investments operate without obvious economic causes and global markets thrive on guesswork and the kind of rationality that most Americans do not practice. And yet Americans from all walks of life have lined up in unprecedented numbers to ride a roller coaster of boom and bust over the previous three decades, willing to invest with leveraged loans and easy money wherever there is a promise of success, despite the fact that time after time, stocks, bonds, and hedge fund failures spiral into losses of myriad jobs and homes. As one middle-class Chicagoan who had lost his overpriced home recently told a journalist, “I just asked the bank to fund me to the max” because “I had this gut feeling I would be safe from foreclosure.” His gut was wrong. According to many of the authors rushing to publish books from their perches close to the epicenter of hedge funds, most of the catastrophes of the last three decades were utterly predictable, yet “the experts” did not dream of averting them.

Perhaps because our habits of building personal investments such as savings accounts, life insurance, and retirement pensions have provided us with real security against crises and infirmity, many Americans are willing to extend such investment-for-security to encompass the riskier forms of investment-as-a-gamble. Most of the time, personal gains are fairly modest and investments grow at a reasonable pace, with reasonable account managers keeping an eye on stock markets for us behind the scenes. But at times we are reminded about the fragility of economies in which the gambling has run amok. The stock market crash of 1987, a subsequent Internet bubble, the Asian currency crisis of the 1990s, overlapping with a Russian bond default that triggered the failure of hedge fund giant John Merriweather, a portfolio insurance implosion, Bernard Madoff and his massive Ponzi scheme, cascades of bank failures, and the sub prime-mortgage bond tsunami, are only some of the recent debacles that have defied regulatory powers and enticed millions of people into schemes that promised riches before the bubbles burst.

The stories of hard times brought on by speculators and hedge fund gurus who drive up the prices of stocks and bonds through great global webs of investment have become too familiar; bailouts and regulations have been woefully inadequate. The general contours of the great public rush of investors eager to get a piece of the artificially inflated riches, followed by stunning losses of private savings, are equally familiar. But how new are the stories? Americans’ fascination with making their dollars grow through paper speculating, and their fortunes and failures resulting from it, has been a subject of scholarly interest for a long time. Historians have chronicled credit and investment schemes beginning in the late-colonial years and continuing in every era of American history. In the two hundred years between the Revolution and the 1980s, over a dozen episodes of overextended credit or speculative frenzies grew into full-fledged financial panics, some followed by years of depression. In many respects, the crashes and panics of the recent past do not differ in kind from previous historical examples, but only in intensity: the cycles of boom and bust bombard Americans more frequently, the fortunes reported are outlandishly greater, the effects spread far more widely, and the losses to millions of people are much more consequential.

Shocked repeatedly, as we have been in recent decades, by swindles and crashes of mind-boggling dimensions, the Panic of 1792 seems to be a minor episode in comparison. After all, Americans had barely begun to build institutions, make their mark in global commerce outside the former empire, and conquer the western wilderness. How much cash and credit could have been available to speculators in so fragile a republic? How deeply could a panic have affected average Americans’ lives, especially when most Americans still thought about wealth in tangible, material ways, and still doubted that piles of paper securities and IOUs could play a viable role in the “true prosperity” of their country?

As they entered the American Revolution, patriots professed that in order to be successful, their Revolutionary War required a higher degree of self-control and moral virtue than anyone had demanded of them previously. Their conception of virtue, which was refined as they assumed responsibility for independence and mobilized all their resources, entailed self-sacrifice, unflinching commitment, and an impeccable regard for the public cause over private agendas for profits. Three major nonimportation movements during the Imperial Crisis joined elite and middling colonists in public pledges to restrain individual desire for more goods of a wider variety by ceasing to consume an array of British imports. Benjamin Rush’s famous words that a citizen was “public property. His time and talents—his youth—his manhood—his old age—nay more, life, all belong to his country,” became a truism at the onset of the Revolution. Corruption, venality, and luxury, republicans insisted, had no place in the American polity.

Yet it was abundantly clear, to those who studied events closely, that civic and moral virtue was insufficient to sustain either the Revolutionary War or the rebuilding that followed. For generations, colonists had looked with ambivalence at merchants who marshaled a whole bundle of privileges, including greater access to credit and investment opportunities than most colonists had. But this perspective faded in the late colonial years; older, customary, notions of an organic harmony of interests, which had been especially manifest during the nonimportation movements, gave way slowly to images of a congeries of individuals in the marketplace of goods and services, where every American’s own private interests were said to have social benefits, in turn validating widespread risk-taking and inviting visions of abundance. The idea of restraining individual desire for more and better goods on behalf of the commonwealth’s welfare would arise now and again in the early republic, but it seemed a curiously outmoded way of thinking to an increasing number of Americans after the Revolution. The prospects of hiking up the prices of agricultural goods to what the market would bear appealed to farmers more and more. The prospects of winning supply contracts that promised to yield exaggerated commissions, or getting privateering contracts that legalized snatching the riches on enemy vessels, swept merchants into the role of business agents to state governments and the Continental Congress on a previously unimagined scale.

Not all revolutionary Americans gained from such thinking and behavior. When dire times set in by 1779, wide sections of the revolutionary movement began to question the consequences of mixing private benefits with the ideal of public virtue. Price inflation, severe currency depreciation, chronic food shortages, selling necessities to the enemy, and the failure of price-fixing were placed at the feet of the most visible scapegoats, the merchants and suppliers entrusted with the well-being of everyone. Although a broad swath of Americans welcomed the greater degree of individual autonomy that the Revolution both promised and made possible for the ambitious, they were not complacent about the new interests that seemed to be so handsomely profiting. Critics took note that only a few Americans, most already well-positioned, could live the promise of free individuals pursuing self-interested opportunities; critics also argued that this self-interest had serious social drawbacks if left unbridled. Their public warnings, spread through a growing print culture in America, turned into petitioning and rioting against those perceived to be responsible for economic injustices in their communities.

The critics were correct in claiming that relatively few Americans prospered, or prospered for long, on the scale that the new rhetoric promoted and promised. But those who were already so positioned in the late colonial era, those few with privileged access to resources in land and commerce, together with the ambitious fast-risers who emerged in the wake of the Revolution, were poised to make the most of—indeed, to create—a speculative fever in the war’s aftermath. New Yorker William Duer, a Revolutionary army supplier and international importer, was among the best at grasping opportunities to move much-needed goods for personal gain. Using false clearances, forging commercial bonds, and collaborating with customs officials at foreign ports, he “greased the way” for goods that supplied both patriots and loyalists. After the Revolution he continued to win Army contracts, but more importantly, he was poised to amass state and federal securities in the wake of the war, buying them at drastically reduced prices and gambling that this debt would be assumed as part of Alexander Hamilton’s federal program and thus grow in value. Duer professed the dawning financial wisdom, that money not only embodied the value of actual goods and labor but also the value of future development and profits. Like other ambitious entrepreneurs, he insisted that the enterprise of myriad Americans would be driven not by the necessity to avoid starvation, as so many early modern theorists had thought, but rather by the incentives of high wages and interest rates, and the availability of extensive credit on easy terms. Likewise, the development of commerce and land need not be bound by the limits of one’s available capital, but “could be furthered with barrels, nay store rooms, full of Revolutionary paper.” Duer, and a consortium of ambitious speculators and risk-takers around him, believed that the 1780s presented a golden opportunity to overtrade in public assets, especially the paper securities of state governments and the Continental Congress.

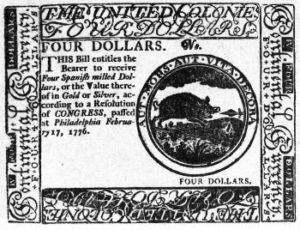

At first, speculators scrambled to accumulate state and Continental Congress currencies at drastically depreciated prices; farmers, veterans, and widows sold the money and certificates issued during the Revolutionary war at a few cents on the dollar in order to raise more usable cash for themselves in the hard times of the 1780s. By the end of the decade, speculators were eagerly purchasing stock in the country’s few state banks and they were looking forward to amassing scrip from the proposed federal Bank of the United States.

There was no shortage of ways for Duer to invest these stocks and securities. Plans to turn the newly independent country toward manufacturing popped up everywhere, though most of them failed for want of capital and plentiful cheap labor. But Duer leaped at the opportunity to develop one such plan, the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (SEUM), in early 1791. Acting as an agent for Alexander Hamilton and Tench Coxe, the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, he mobilized the corps of mid-Atlantic speculators who held bundles of state and federal securities issued during the Revolution; having purchased these “barrels” of paper from veterans, suppliers, and army agents at a fraction of their face value, Duer’s circle was poised by the end of the 1780s to invest or resell these securities to another layer of speculators—middling Americans with their own deep ambitions—at enormous profits. So long as a federal financial plan was not yet in place, including the much-talked-about Bank of the United States, the speculators could not be certain that their fistfuls of paper would be redeemed at the level of profit they wished to gain. But Duer acted as if the rumors and wishes would soon come to pass. He assumed authority over the sums amassed for the SEUM—especially wartime securities of state and Congressional governments—and used their prestige to attract further investors who sank their private savings in the project. Then, before building a single manufactory or mill on the SEUM site, Duer and his associates used the SEUM’s precarious paper funds to speculate in different schemes in New York and New Jersey. To top it off, they ran state-chartered lotteries that granted SEUM investors the privilege of raising still more funds to indemnify themselves from losses in the value of their investment, should the SEUM not work out. Investors promised to bring skilled labor and machinery for manufacturing, attract miners and equipment to take iron and copper from nearby hills, and build stores and homes for future migrants. But the site, the future Paterson, New Jersey, became, instead, an opportunity for a few men to “make a bubble of this business” from stock shares, wartime securities, and unpaid loans from friends.

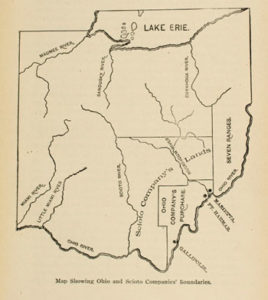

Then, too, there were Duer’s dreams of colonizing land beyond the original states. Like numerous speculators of his day, Duer obtained a vast tract of land from Congress, based on his promise to raise a small fraction of the land’s cost quickly, make further payments much later in the future, and settle migrants on surveyed tracts. He formed a syndicate to settle the Scioto tract, stretching over 4 million acres along the Ohio River, with French immigrants. However, within months after a few families arrived and crossed into the Ohio Valley, Duer’s debts to Congress went unpaid, his promissory notes were rejected in France, and suppliers who sent goods to the new Ohio towns begged for payments. The small nucleus of French settlers languished from hunger and vulnerability to Indian attacks, and then dispersed. Duer fared just as poorly in developing land in Maine and along the Mississippi River near St. Louis.

Duer and the circle of speculators around him believed their securities would continue rising in value so long as the Hamiltonian plan for public credit and a central bank was put into place, and so long as the Bank of New York continued to make loans to Duer for his speculations. Rumors surfaced in spring 1791 that Duer’s circle was cornering the newly issued scrip of the Bank of the United States, borrowing heavily in order to buy the scrip, on the expectation that its value would rise. However, after an initial surge in scrip and securities prices, values fell precipitously in mid-1791. On guard against the potential for a complete collapse of credit and prices across the nation, Hamilton initiated a kind of bailout, in which the Treasury purchased large amounts of circulating securities in order to restore their higher values. When the Bank of New York refused Duer further loans to buy securities and cover his debts, Hamilton lamented that however irresponsible Duer had been with other people’s money, his downfall would harm thousands of Americans and the economy overall. Reluctantly, Hamilton instructed the Bank to buy Duer’s stock at market prices, thereby averting his ruin and a tremendous shock to the economy that autumn.

Yet, despite the need for government support and a publicity campaign warning Americans about the dire effect that any speculative craze would have on the economy’s stability, the Duer circle was buoyed into a new frenzy of securities and stock-buying by the end of 1791, and planned to corner the market on federal securities in order to sell them at inflated prices to not only those whose appetites for speculation were already whetted, but also to “my fellow inhabitants of this city [New York] and far beyond.” Rumors held that Duer not only speculated on the first shares of the Bank of the United States, using information gleaned from the first stock holders’ meeting to time his purchases, but he also demanded advances from the SEUM and his land companies, as well as extensive loans from his erstwhile friends, to buy “as much paper as my chests will hold.” By late 1791, his obligations far outran his ability to pay, so he widened his circle of speculation further and scrambled to borrow “small sums” at usurious rates from “shopkeepers, widows, orphans, butchers, cartmen, Gardeners, market women & even the noted Bawd Mrs. McCarty.”

Duer’s paper castle began to crumble in the early months of 1792 when overdue debts plagued him and the Bank of New York closed its doors to him. The First Bank slowed the expansion of its loans and contracted its supply of circulating banknotes, which forced a general credit contraction throughout the economy. Soon the Federal government initiated a suit for repayment on Duer’s army contracts and land holdings. When small lenders came forward in distress, he blamed his problems (which were just as much their problems) on brokers and agents who “acted outside my authority;” he stopped payments on his obligations just as the general fall of stocks and reputations caught up with him in early 1792. Like many of the credit crises in our times, there was no great precipitating international event, no war or revolution, that initiated the generalized collapse.

The Panic of 1792 did not generate a bailout plan. At first, mobs of small note holders who despaired of getting their money back held Duer virtually a prisoner in his house. Within weeks, his larger creditors took the additional step of committing him to the city prison, where he lived out most of the rest of his days. Duer’s debt to scores of Americans was so enormous that his own undoing was only a beginning to the panic. In the ensuing confusion “Speculators fought like Dogs, Cursing & abusing each other like pick pockets & trying every fraud to prey on each other’s distress” over the rapid decline in securities values. Some sold off their own securities and defaulted on loans, adding to the contagion; some fled the city to evade lenders; others in Duer’s circle landed in jail, and many people who trusted him with their small savings went to the poor house. By March, food prices rose, “and as for confidence there [was] no such thing.” Hamilton, who continued to believe that public offices were best tended by men who anticipated private rewards, kept a safe distance from New York. From Philadelphia, where the new Bank of the United States offices were headquartered, he engineered huge open-market purchases of bank stocks, which helped manage the national financial market by prompting a rise in stock prices and restoring some of the Bank’s lost credibility. Four years later the state of New York refused to lighten the laws concerning debt and bankruptcy, for fear Duer would be released and “get in the game again.” He never did; Duer died in his prison cell in 1799.

Was the excess of self-interest that provoked the Panic of 1792 any more or less consequential than the periodic crises engineered by our own era’s Mad Hatters? Measured in dollars, the post-Revolutionary generation’s speculative fever was miniscule compared to trading done now on Wall Street. Post-Revolutionary Americans also practiced more face-to-face negotiations over loans and credit, and lived within a more interpersonal matrix of trust and reputation, than our own generation’s traders who buy stocks online and build portfolios with Wall Streeters they will never (and perhaps never care to) meet. The international reach of men like Duer was hardly comparable to the complicated and interdependent reach of postmodern capital markets today. Perhaps those Americans endowed with inside information and social access are prone to a form of blindness that admits the light of potential profits to be garnered from fistfuls of securities while shutting out any light that might illuminate dire outcomes, no matter what era they live in. But what is it that entices so many people of all walks of life to gamble with life savings? What makes them too arrogant to guard against overextending themselves? Like our recent hard times, the Panic of 1792 drew scornful attention to the agents of speculation and the evils of overdrawn credit; people pointed fingers and agreed that men such as Duer deserved to languish somewhere out of sight. And yet, before the panic, that same bandwagon was crowded with an eager public investing its small sums in an unpredictable future built on scraps of paper. In that respect, little seems to have changed. For every Duer historians meet in the sources for 1792 there is a John Merriweather or a Bernard Madoff two hundred years later.

Further reading

On the Panic of 1792, I offered one interpretation in Cathy Matson, “Public Vices, Private Benefit: William Duer and His Circle, 1776-1792,” in Conrad Edick Wright, ed., New York and the Rise of American Capitalism: Economic Development and the Social and Political History of an American State, 1780-1870 (New York, 1989), 72-123. For parallel stories of paper and land speculation, financial insecurity, and the speculating mania of Americans during the 1780s and 1790s, see Bruce Mann, Republic of Debtors: Bankruptcy in the Age of American Independence (Cambridge, 2002); Jane Kamensky, The Exchange Artist: A Tale of High-Flying Speculation and America’s First Banking Collapse (New York, 2008); Allan Taylor, The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution (New York, 2007); and Lawrence A. Peskin, Manufacturing Revolution: The Intellectual Origins of Early American Industry (Baltimore, 2003). Thanks to Christian Koot and Ken Cohen for their insights.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.3 (April, 2010).

Cathy Matson is Professor of History at the University of Delaware and Director of the Library Company of Philadelphia’s Program in Early American Economy and Society. She has written books and articles on the political economy and economic culture of colonial and early national years and is currently at work on her fourth book, “A Gamblers’ Ocean: The Economic Culture of Commerce in Philadelphia, 1750 to 1811.”