Early in the last decade, an Ayn Rand disciple named Alan Greenspan, who had been trusted with the U.S. government’s powers for regulating the financial economy, stated his faith in the ability of that economy to maintain its own stability: “Recent regulatory reform coupled with innovative technologies has spawned rapidly growing markets for, among other products, asset-backed securities, collateral loan obligations, and credit derivative default swaps. These increasingly complex financial instruments have contributed, especially over the recent stressful period, to the development of a far more flexible, efficient, and hence resilient financial system than existed just a quarter-century ago.”

At the beginning of this decade, in the wake of the failure of Greenspan’s faith to prevent the eclipse of one economic order of things, Robert Solow, another towering figure in the economics profession, reflected on Greenspan’s credo and voiced his suspicion that the financialization of the U.S. economy over the last quarter-century created not “real,” but fictitious wealth: “Flexible maybe, resilient apparently not, but how about efficient? How much do all those exotic securities, and the institutions that create them, buy them, and sell them, actually contribute to the ‘real’ economy that provides us with goods and services, now and for the future?”

Solow’s distinction between the “real” economy and the “exotic” realm of securitized debts like mortgage bonds, credit default swaps, toxic debt, and zombie banks is not uniquely his. As a widespread assumption—a persistent distinction in our thought between “real” and “fictive” money, wealth, or productivity—it may be one factor that accounts for the reluctance of many historians to delve into financial dynamics when seeking to account for “Hard Times.” Reflexively, we analyze such dynamics with the tools of the linguistic turn, and so spend our time demonstrating that the fictions on which economic actors build their worlds are, in fact, fictional. (Most historians are also reluctant—maybe even unprepared—to work with numbers.) But when collective euphoria, financial innovation, and astonishing disproportions of power mix together, what bubbles into being is anything but mere vapor. We can minimize its weight by calling it fiction, but we do so only at grave risk to our understanding of what happened and why. For in such financial exchanges we see not only the generation and transfer of real wealth—that is, real effects in the social and political world—but also that such transfers can incorporate great violence and disruption for some as the causes of great profit for others.

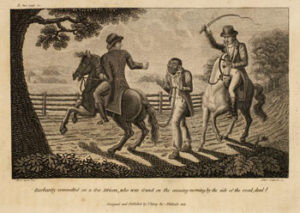

Read casually through the pieces of paper that document Jacob Bieller’s life and enterprises, and this planter of Concordia Parish, Louisiana might look like someone who lived not just thousands, but millions of miles away from the center of international financial markets in the 1830s—and his business might seem even more distant in kind from the markets that worry us in our own day. Browse through the letters between Bieller and his son Joseph, the latter writing from the bank of Bayou Macon, thirty miles or so from Jacob’s own place on the Mississippi River. Joseph wrote his father in an untutored orthography, recounting the events of life on a cotton labor camp, or what contemporaries called a plantation: “I shall be short of corn,” or someone has found the body of the father of Enos, Bieller’s overseer, the old man having “drownded in Deer Drink.” The cyclical rhythm of forced agricultural labor thrummed onward—”I send you by Enos fifteen cotton pickers they are all I can spare. We have twelve thousand weight of cotton to pick yet from the appearance of the boals yet to open.” Always the urge to extract more product clashed with the objection of the enslaved to their condition: “I have had a verry sevear time among my negros at home. they have bin swinging my hogs and pigs. Harry & Roberson I caught. I stake Harry and gave him 175 lashes and Roberson 150. since that I found two hogs badly crippled.” You can almost see the Spanish moss on the low branches, parting as the whining hog lurches out; can picture Enos’s father as he poles his pirogue. His booted foot slips on the wet edge; you hear him splashing frantically as the dark water gurgles.

For good and for ill, though, there is much more in common than what we might initially suspect between Jacob Bieller and—for instance—the men and women who “broke the world” in the most recent collapse of the global financial system. The Panic of 1837 launched America’s biggest and most consequential economic depression before the Civil War. And it was the decisions and behavior of thousands of actors like Bieller that created a perfect financial storm: bringing an end to one kind of capitalist boom; destroying the confidence of the slaveholding class, impoverishing millions of workers and farmers who were linked to the global economy; demolishing the already disrupted lives of hundreds of thousands of people like Harry and Roberson. Historians have usually described the Panic of 1837 differently, fitting it in their own categorical boxes: Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., the court historian of New Deal Democrats, saw “the business community,” with their “dizzy pyramiding of paper credits,” as the problem. Historians of American banking, usually a specialized breed interested in, what else, banking, often blame the Panic on Andrew Jackson—in their telling, an ignorant lout obsessed with the idol of precious metal. For them, the cause of the Panic was the Specie Circular of 1836, which forced U.S. government agencies to stop accepting the paper banknotes pumped out by state-chartered banks and to demand specie (metal coins: gold or silver, usually) in payment for federal land and other obligations.

These versions of the Panic are capsules that carry other versions of the history of American capitalism into the bloodstream of historical consciousness. Was the Panic the result of a struggle between factory owners and factory workers, with a dash of hardy Jeffersonian farmers suspicious of the new way of making money? No, it was created by a struggle for greater efficiencies, a process of sweeping away old institutions and prejudices so that the market could be all in all! Yet we have received a recent education in booms and busts, bubbles and panics, one that alerts us to other stories. The first lesson we have learned (or relearned) is that a financial crisis is a mighty and powerful thing. The actors will respond to its impact with language and we historians will want to interrogate those words with the tools of cultural history. Surely it is significant that businessmen were “embarrassed” when their “friends” would not “sustain” their “credit” (Note how the scarequotes “problematize” each word, demanding that we unpack its contextual meaning.) Yet if that is all historians care about, they leave the mechanics of historical financial crises to the court historians of the great banking dynasties, or to economists. The history of financial panics reminds us that we have to integrate the study of big, impersonal forces with the study of how people shape meaning out of their individual lives.

If we look closely at the transformations and innovations that led to the Panic of 1837, we find new evidence about the role of slavery and slave labor in the creation of our modern, industrialized—and post-modernly financialized—world. Look a little more closely at Jacob Bieller, who can tell us things worth the due diligence. In 1837 Bieller was 67 years old. He had grown up in South Carolina, where in the first few years of the nineteenth century he and his father took advantage of that state’s reopening of the African slave trade and speculated in survivors of the Middle Passage. In 1809, little more than a year after Congress closed the legal Atlantic slave trade, Bieller moved west. Driven in part by divorce from his first wife, but drawn by the opportunities for an entrepreneurial slave owner in the new cotton lands opening to the west, Bieller took his son Joseph and 27 enslaved African Americans and settled just up the Mississippi River from Natchez, on the Louisiana side.

The enslaved people that Bieller brought to Concordia Parish became the root of his fortune—as they and a million others like them would become the root of the prosperity of not just the antebellum southwestern states, but of the United States as a whole. And perhaps one could go further than the U.S. By the 1830s, the cotton that enslaved people grew in the new states and territories taken from Native Americans in the early nineteenth century was the most widely traded commodity in the world. Its sale underwrote investments in new forms of enterprise north of slavery. It was also the raw material of the industrial revolution. The creation of textile factories in the British Midlands launched a process of continuous technological innovation, urbanization, and creation of markets that broke the Malthusian traps of traditional agricultural society. First Britain, and then the U.S., and then the rest of Western Europe achieved sustained rates of economic growth never before seen in human history.

The easy way out is to credit this astonishing growth to the increasing division of labor and high pace of technological innovation—the spinning jenny, the mechanical loom—that emerged in the eighteenth-century British manufacturing sector. But world historian Kenneth Pomeranz insists that we also have to look at the capacity of environments to produce resources if we want to understand what really allowed the West to emerge from the rest of the pack. The cotton fields of the slave South were particularly crucial because they allowed Britain to break out of its own “cul-de-sac” of resources: the limits imposed by the delicate balances between labor, land, fuel, food, and fiber that kept such a revolution from occurring in other societies. Even if every acre in Britain were converted into fiber production, the island would have been incapable of matching the capacity of the slave South to produce the raw materials for a textile-based economic transformation, to say nothing of the labor that would have to be taken out of the pool of potential factory workers to produce fiber.

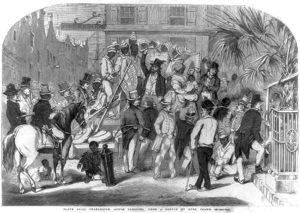

When Jacob Bieller put his two dozen slaves to work growing and picking cotton, his whip was also driving the creation of a new, more complex, more dynamic world economy. In the lifetime between the ratification of the Constitution and the secession of the Confederacy, enslavers moved more than a million enslaved African Americans to cotton-growing areas taken by the new nation from their original inhabitants. Forced migrations and stolen labor yielded an astonishing increase in cotton production: from 1.2 million pounds in 1790 to 2.1 billion in 1859, and an incredible dominance over the international market—by the 1830s, 80% of the cotton used by the British textile industry came from the southern U.S.

We live today with the results of the long days that Bieller’s slaves sweated out in the field, but we also live in a world distantly shaped by the financial decisions of cotton entrepreneurs on both sides of the Atlantic—as well as by the forgetfulness of those who have not learned from their lessons of two centuries ago. Specifically: their decisions about how to obtain and use credit, as well as to manage risk. And there was risk aplenty. Up and down the chain of (mostly white) people who sold, traded, shipped, and speculated on the cotton that enslaved people made, credit and risk were imminent to the task of moving the world’s most important commodity through a chain of buyers and sellers that stretched from Louisiana cotton field to Liverpool cotton exchange. Prices suddenly dropped when rumors raced through New Orleans, New York, or Liverpool: “Optimism prevailed”—till the market learned that the U.S. crop is too big for the demand this year. Cloth isn’t selling because of “overproduction.” The mill workers in Manchester have been “turned out”—laid off.

When rumors of bad news overwhelmed the desire for speculative gain—when the “animal spirits” of the marketplace, to use a term coined by John Maynard Keynes, turned negative—a massive, systemic crash could result. This is what almost happened in 1824-1825, when cotton buyers were initially convinced that the 1824 crop was small. After buying all the bales that they could at rising prices, middlemen discovered that in fact the crop had been very large. Beginning with Adam Smith, utopian economists have argued that the logical outcome of profit-maximizing behavior by all market actors is the maximum collective benefit. In this case, when the price of a pound of cotton plummeted, merchant firms were unable to pay back the short-term commercial loans they had taken, and so they demanded repayment from their fellow firms to whom they had made loans. This individually rational behavior—shoring up liquidity as pressure for payment increased—led to collectively irrational outcomes. Every firm was suddenly moving in the same direction, every firm faced the same crisis, each one responded in the same way. The result was crash and paralysis in the British cotton and credit markets.

The mini-crash of 1824-26, like every financial panic, underlined the problem of systemic risk. The fact that the mid-decade’s outbreak of animal spirits did not end in full-scale economic disaster in the U.S. was a result, some believed, of the expanded ability of the Second Bank of the United States to regulate the level of systemic risk in the American economy. Under the direction of Nicholas Biddle the B.U.S. fulfilled many of the functions of a modern central bank. By forcing smaller, state-chartered banks to redeem their own credit in highly convertible currency, like gold dollars, British pounds, or banknotes of the B.U.S. itself, Biddle’s Bank kept a tight rein on those institutions. They could not issue too much credit. By making and by calling in its own loans, the B.U.S. also “curtailed” speculation on the part of private individuals. The B.U.S. ensured a level of systemic stability that in turn enabled individual market participants to devise workable strategies for hedging against individual counterparties. To avoid the possibility that they might be left holding the hot potato if cotton prices dropped suddenly, middlemen began insisting on shipping cotton bales on consignment. This meant that planters still owned their crop and bore much of the risk of a drop in price, up until one of the buyers working for the Manchester textile companies purchased it.

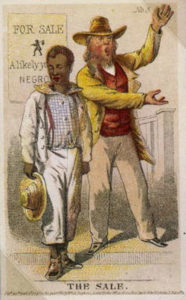

The Bank not only worked to prevent financial panics but to drive steady growth. As the single biggest lender in the economy, it lent directly to individual entrepreneurs—including enslavers like Jacob Bieller, who were always eager to buy more human capital whom they could put to work in the cotton fields of the southwest. “The US Bank and the Planters Bank at this place has thrown a large amt of cash into circulation,” wrote slave trader Isaac Franklin from Natchez in 1832. Franklin was the Sam Walton of the internal slave trade in the U.S., selling hundreds or even thousands of men and women in New Orleans and Natchez in a given year. In fact, by the early 1830s, the Natchez and New Orleans branches had lent out a full third of the capital of the B.U.S., much of it used to buy thousands of enslaved people from the Chesapeake, Kentucky, and North Carolina. Some of the lending was in the form of renewable “accommodation loans” to large-scale planters who were members of, or connected to, the clique of insiders who ran the B.U.S. branch and the series of state banks chartered by the Mississippi government. Even more of the lending was in the form of commercial credit to cotton buyers. This kept the price of cotton steady and, finding its way to the planters themselves, inspired Natchez-area enslavers to buy more of the people that Franklin and others were purchasing in the Chesapeake states and shipping to the Mississippi Valley.

While planters like Jacob Bieller waited for payment, merchants like the Natchez broker Alvarez Fisk, a Massachusetts-born man who funneled bank money to planters and cotton to Liverpool, lent them operating funds. But ultimately the entire structure was bottomed on, founded on, funded by the bodies of enslaved people: on the ability of slaveholders to extract cotton from them, and on the ability of slaveholders (or bankruptcy courts) to sell them to someone else who wanted to extract cotton. And the fact that cotton fields were the place where the margins of growth were created meant that they presented lenders with both needs and opportunities to hedge against the risk that individual counterparties would default.

For there were many things that could cause individual counterparties, especially planters, to fail. They depended on the bodies and the lives of people whom they also brutally exploited, beginning with their forced migration to a deadly environment. The cotton country of the Mississippi Valley was hot and wet, and the people transported there died of fevers in great number. One of the chatty letters written by Daniel Draffin, an Englishman Jacob Bieller hired to tutor his grandchildren, described the mosquitoes that flew in phalanx formation: “I have been out gunning when I could not take sight they were so numerous.” Mosquitoes loved all of the new blood; and there was plenty of it: 155,000 transported from the old slave states to the new ones in the 1820s, for instance, according to the best existing estimate. And other diseases besides malaria thrived in the radically new environment of the ghost acres. In 1832-33, cholera raged through the slave labor camps of Mississippi and Louisiana, carried on the same steamboats that brought new slaves in and took cotton out. At the “Forks in the Road,” the huge slave market just outside of Natchez, Isaac Franklin desperately hid the evidence of epidemic among his “fancy stock of wool and ivory,” as his cousin coarsely put it. “The way we send out dead negroes at night and keep dark is a sin,” wrote Isaac about secret burials in the woods behind his barracoon. He kept the secret hidden, and the price of men up at $700 per, until “I sold Old Man Alsop’s two scald headed boys for $800 one of them Took the Cholera the day afterwards and died and the other was very near kicking the Bucket.” During boom times in particular, death rates for the enslaved in the new southwestern states and territories were comparable to those in the Caribbean, or in the lowcountry of South Carolina.

Then there was simple failure, sometimes for reasons endemic to slavery’s new frontiers, sometimes not. Even as cotton markets soared in the 1830s, Jacob Bieller, for instance, plunged into his own personal crash. His daughter by his second marriage eloped with an ambitious young local lawyer named Felix Bosworth. She was only fifteen or so, but it seems likely that Bieller’s wife, Nancy, encouraged the elopement because she quickly left home to join her daughter, and began divorce proceedings—claiming half of Bieller’s property. According to Nancy, not only had Jacob threatened to shoot her in 1827, but for years “he kept a concubine in their common dwelling & elsewhere, publicly and openly.” (The courts of Louisiana declined to rule on either charge when they eventually granted the couple a divorce. Jacob’s last will gave tacit freedom “to my slaves Mary Clarkson and her son Coulson, a boy something more than five years old, both bright mulattoes.”)

In a moment of despair, Jacob wrote on the cover of a family bible that his daughter’s elopement had “destroyed my welfare, family, and prospects.” But it was clear that the ultimate hedge for him, for Nancy, and for Alvarez Fisk and Isaac Franklin, was the relative liquidity of enslaved people. (Bieller had recently purchased dozens of additional slaves on credit from Isaac Franklin, paying more than $1,000 each, bringing his total number of captives to over eighty). All he and Nancy had to debate about was the method—he wanted to sell all those determined to be community rather than separate property, and divide the cash. She wanted to divide the men, women, and children up, “scattering them,” she wrote, intentionally. Enslaved people, Nancy said, were “susceptible to a division in kind without injury to us.” Or to a sale, so long as the system was not in crisis and there was a steady market, Jacob could have retorted. Either way, the families of the almost one hundred people listed in Bieller’s documents would be melted like ice in his summer drink.

For everyone who drew profit in the system, enslaved human beings were the ultimate hedge. Cotton merchants, bankers, slave traders—everybody whose money the planter borrowed and could not pay until the time the cotton was sold at a high enough price to pay off his or her debts—all could expect that eventually enslaved people would either 1) make enough cotton to enable the planter to get clear or 2) be sold in order to generate the liquidity to pay off the debt. In 1824, Vincent Nolte, a freewheeling entrepreneur who almost cornered the New Orleans cotton market more than once in the 1810s, lent $48,000 to Louisiana-based enslaver Alonzo Walsh. The terms? Walsh had to pay the money back in four years at a rate of about eight percent. To secure payment he committed to consigning his entire crop each year to Nolte to be sold in Liverpool. And, just in case, he provided collateral: “from 90 to a 100 head of first rate slaves will be mortgaged.” In 1824 those nearly five score people meant up to $80,000 on the New Orleans auction block—a form of property whose value fluctuated less than bales of cotton.

Yet enslavers had already—by the end of the 1820s—created a highly innovative alternative to the existing financial structure. The Consolidated Association of the Planters of Louisiana (despite its name, the “C.A.P.L.” was still a bank) created more leverage for enslavers at less cost, and on longer terms. It did so by securitizing slaves, hedging even more effectively against the individual investors’ losses—so long as the financial system itself did not fail. Here is how it worked: potential borrowers mortgaged slaves and cultivated land to the C.A.P.L., which entitled them to borrow up to half of the assessed value of their property from the C.A.P.L. in bank notes. To convince others to accept the notes thus disbursed at face value, the C.A.P.L. convinced the Louisiana legislature to back $2.5 million in bank bonds (due in ten to fifteen years, bearing five percent interest) with the “faith and credit” of the people of the state. The great British merchant bank Baring Brothers agreed to advance the C.A.P.L. the equivalent of $2.5 million in sterling bills, and market the bonds on European securities markets.

The bonds effectively converted enslavers’ biggest investment—human beings, or “hands,” from Maryland and Virginia and North Carolina and Kentucky—into multiple streams of income, all under their own control, since all borrowers were officially stockholders in the bank. The sale of the bonds created a pool of high-quality credit to be lent back to the planters at a rate significantly lower than the rate of return that they could expect that money to produce. That pool could be used for all sorts of income-generating purposes: buying more slaves (to produce more cotton and sugar and hence more income) or lending to other enslavers. Clever borrowers could pyramid their leverage even higher—by borrowing on the same collateral from multiple lenders, by also getting unsecured short-term commercial loans from the C.A.P.L., by purchasing new slaves with the money they borrowed and borrowing on them too. They had mortgaged their slaves—sometimes multiple times, and sometimes they even mortgaged fictitious slaves—but in contrast to what Walsh had to promise Nolte in 1824, this type of mortgage gave the enslaver tremendous margins, control, and flexibility. It was hard to imagine that such borrowers would be foreclosed, even if they fell behind on their payments. After all, the borrowers owned the bank.

Using the C.A.P.L. model, slaveowners were now able to monetize their slaves by securitizing them and then leveraging them multiple times on the international financial market. This also allowed a much wider group of people to profit from the opportunities of slavery’s expansion. Perhaps it was no accident that the typical bond issued by the C.A.P.L. and the series of copycat institutions that followed was denominated at $1,000, which was roughly the price of a field hand. For the investor who bought it from the House of Baring Brothers or some other seller, a bond was really the purchase of a completely commodified slave: not a particular individual, but a tiny percentage of each of thousands of slaves. The investor, of course, escaped the risk inherent in owning an individual slave, who might die, run away, or become rebellious.

Between 1831 and 1834, for reasons about which historians have argued long and hard (without, alas, reaching consensus), President Andrew Jackson fought a brutal battle against the Second Bank of the United States. The Bank had pumped millions of dollars of loans into Mississippi and Louisiana in Jackson’s first term—almost half of the Bank’s total balance sheet was there by 1832—but it remained unpopular in the large sections of the southwest. Creditors are not always loved among those to whom they lend. Jackson vetoed the recharter of the B.U.S. in 1832, and won reelection that fall against a pro-Bank opponent. The next year, he ordered the transfer of the government’s deposits out of the Bank. Jackson claimed that by giving the B.U.S. effective control over the financial market, the federal government had made “the rich richer and the potent more powerful.” No doubt it had done so. But he distributed the deposits to a horde of so-called “pet banks”—state-chartered institutions that, at least initially, were run by his political allies—who in turn were often not members of the old cliques that had run the banks that the B.U.S. treated as favorites. In reaction, Biddle called in millions of dollars of loans, provoking a recession that began in late 1833. In early 1834, however, the B.U.S. had to concede and move on to doing business as a still large, but significantly shrunken ordinary bank. Now, nothing—no bank, no other institution—regulated the financial economy of the U.S.

The utopian faithful, more like Greenspan than like Keynes, have controlled both academic economics and economic policy-making over the last quarter-century. They have argued that a self-regulating market will unleash innovation, leading to the best possible outcome. The history of the 1830s, however, suggests otherwise—insisting, instead, that unregulated financial markets permit financial innovation that then leads to speculative bubbles. They in turn popped, as bubbles do. The consequences can be massive, complex, and lasting.

Economists of financial crisis such as the late Hyman Minsky and Charles Kindleberger (names unfashionable before 2008), argued that most historical bubbles contain three crucial elements: policymakers who believed markets were stable and did not need regulation; financial innovations that make it easier to create and expand the leverage of borrowers; and what economic writer John Cassidy helpfully shorthands as “New Era thinking typified by overconfidence and disaster myopia.” By “New Era thinking” he means those who believe that, to quote the title of another recent work on financial panics, “This Time is Different”—that the rules have changed and prices will continue to climb. Belief leads one to want to buy into speculation, even if one must assume large debts to do so, because one is confident that prices will keep rising and one can sell to some other buyer further down the road. In this way, every boom takes on aspects of a Ponzi scheme. “Disaster myopia,” meanwhile, refers to the common propensity of economic actors to underestimate both the likelihood and the likely magnitude of financial panic. The magnitude is exacerbated by the extent of indebtedness (entered into because of overconfidence) and the degree to which individual hedging and unregulated over-leveraging make it likely that pulling one card will bring down the whole structure.

The anti-B.U.S. elements in Jackson’s administration did not replace Biddle’s institution with any other check within the financial system, opening the way for all three developments. State politicians, to whom the ball was in effect handed, apparently assumed that nothing could go wrong. After 1832, the securitization, world-wide marketing, and multiple leveraging of enslaved people, pioneered by the C.A.P.L., proliferated. Across the southwest, cotton entrepreneurs created a series of banks, many of them far larger than the C.A.P.L. In 1832, the state of Louisiana chartered the Union Bank of Louisiana, which issued $7 million in state bonds. The bank contracted with Baring Brothers to sell them, and Baring sent some to their American partners, Prime, Ward, and King in New York City. Soon Union Bank securities were circulating in all the financial centers of Europe and North America. Next, in 1833, came the mammoth Citizens’ Bank of Louisiana, which was capitalized with an issue of $12 million in bonds that Hope and Company in Amsterdam agreed to market.

Still the Louisiana legislature churned out new bank charters. The New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad and Banking Company—$3 million. The New Orleans Gas Light and Banking Company—$6 million. And on and on, until, by 1836, New Orleans was, per resident, the U.S. city with the greatest density of bank capital—$64 million in all. Other states and territories in the area, self-consciously copying Louisiana, began to create new banks of their own, each one exploiting the loopholes of the now-unregulated system with innovative financial devices. Mississippi issued $15.5 million in state bonds to capitalize its own Union Bank. Alabama did not issue state bonds, but the Rothschilds, financiers of London and Paris and bitter rivals of the Baring Brothers, invested heavily in Alabama’s banking system. Florida sold $3 million dollars of bonds to capitalize its own Union Bank, and another million or so for smaller institutions. Arkansas, with almost no residents, did something similar. By the end of the 1830s, the state-chartered banks of the cotton-growing states had issued bonds for well over $50 million dollars.

Armed with repeated infusions of new cash lent by banks who handed it out with little concern for whether or not mortgaged slaves had already been “hypothecated”—assigned to someone else as a hedge against loans—southwestern enslavers brought tens of thousands of additional slaves into the cotton states. Some of the purchasers were long-time residents in states like Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi. Some were new migrants fired by the “spirit of emigration,” the belief that “there is scarcely any other portion of the globe” that could permit “the slave holder or merchant of moderate capital” to convert said capital into a fortune. They calculated the money that they would make: from the labor of one “hand”—one enslaved person in a cotton field—”between three and four hundred dollars” a year, said one man who thought his expectations modest—”though some claim to make six or seven hundred dollars.” Not bad returns for an “asset” purchased for only two or three times that amount, which could also be mortgaged to produce multiple streams of income. So migrants and longterm residents alike trooped to the banks, mortgaged property (some of which, later critics would charge, did not even exist) and spent the credit they received. Huge amounts of money were shifted around: to slave traders, to the sellers of goods like food and cheap clothing, to slave owners in the Chesapeake who sold people to the southwest, to the banks in Virginia and elsewhere who took their slice of profit as the financiers of the domestic slave traders. By the time the decade was out, at least 250,000 enslaved men, women, and children had been shifted from the old terrain of slavery to the new. There they were set to work: clearing forests from which Native Americans had recently been evicted by Andrew Jackson’s policies; planting cotton seed; tilling it while the harvest neared.

A quarter million people were moved by force, sold, mortgaged, collateralized, securitized, sold again 3,000 miles from where they actually toiled. Each summer they learned how to pick the fields clean faster, at the end of a whip. From 1831 to 1837, cotton production almost doubled, from 300 million pounds to over 600 million. Too much was reaching Liverpool for Manchester to spin and weave, much less to sell to consumers in the form of cloth. Prices per pound at New Orleans, which had begun the boom in 1834 at eighteen cents, slipped to less than ten by late 1836. “Everybody is in debt neck over ears,” was the word from Alabama, but slave “traders are not discouraged”—many of their buyers believed that cotton prices would begin to climb again. They had no evidence to suggest a return to rising prices. Supply clearly exceeded demand. Yet here was the psychology, the animal spirits of the typical bubble at work, saying: this time is different. But as the slowing prices began to pinch, the Bank of England, alarmed at the outflow of capital to the U.S. in the form of securities purchases, cut its lending in the late summer of 1836. (At the about the same time, Andrew Jackson issued his Specie Circular, which slowed the purchases of public land, but appears to have had little effect on what transpired next in the cotton market.) Merchant firms subsequently began to call in their loans to each other.

In early 1837, a visitor to Florida, which was already—as it has ever been—one of the most bubble-prone and speculative parts of the U.S.—wrote that “there is great risk to the money lender and paper shaver—for the whole land, with very few exceptions, are all in debt for property and a fall in cotton must bring a crash with most tremendous consequences to all trades and pursuits.” Back in Britain, the crash had already begun. Three massive Liverpool and London firms, unable to meet their commercial debt because cotton prices had dropped, collapsed at the end of 1836. The tsunami rushed across the ocean to their trading partners in New Orleans. By late March each of the top ten cotton-buying firms there had collapsed.

Except for planters, who were mostly debtors, almost every market actor—cotton merchants, dry-goods merchants, Southern bankers, Northern bankers—now realized that they were both creditors and debtors. But as they scrambled to collect debts from others so that they could pay off their own, two things were happening. The first was that their individually rational pursuit of liquidity created the collectively irrational outcome of systemic failure. No one was able to pay debts, and so most buying and selling ground to a halt. An attempt to restart the system failed. A second, bigger crash in 1839 finished off many of the survivors of the 1837 panic. During those two years, meanwhile, a second consequence had emerged: the discovery that most of the debt owed by planters and those who dealt with them was “toxic,” to use a recent term. It was unpayable. The planters of Mississippi owed New Orleans banks alone $33 million, estimated one expert, and could not hope to net more than $10 million from their 1837 crop to pay off that debt. Nor could they sell off capital to raise cash because prices for slaves and land, the ultimate collateral in the system, had plummeted as the first wave of bankruptcy-driven sales tapped what little cash there was in the system. This meant that the financial system wasn’t just frozen, but that many creditors’ balance sheets were overwhelmed.

After the cotton-brokerage and plantation-supply firms, the next to go were the southwestern banks, whose currency and credit became worthless. They were unable to continue to make coupon payments—interest installments on the bonds they had sold on far-off securities markets. Some might have been able to collect from their debtors by foreclosing mortgages on slaves and land, but, of course, the markets for those two assets had collapsed. Many slave owners had layered multiple mortgages on each slave, meanwhile, and were using political leverage to protect them from the consequences of their financial over-leverage. The ultimate expression of this practice was the repudiation of the government-backed bonds by the legislatures of several southwestern states and territories, most notably Mississippi and Florida—in effect, they toxified the bonds themselves, emancipating slave-owning debtors from the holders of slave-backed securities. The power of the state had created the securitized slave, and now the power of the state destroyed it, in order to protect that slave’s owner from his creditors.

But not all debts could be repudiated. And many of the creditors were located in northern states. Their attempts to collect increasingly brought Southern planters to calculate the value of the Union. Nor could Southern entrepreneurs recapitalize their own institutions. After repudiation, outside investors were cautious about lending money to Southern institutions. In the 1830s it was still not clear where the center of gravity of the national financial economy was located—Philadelphia, home of the B.U.S., and New Orleans were both in contention. By the early 1840s, Wall Street and New York had emerged as the definitive victor. Slave owners continued to supply virtually all of the industrial world’s most important commodity, but the post-1837 inability of Southern planters to control their own financing or get the capital that would enable them to diversify led them to sacrifice massive skimmings of their profits to financial intermediaries and creditors. They sought greater revenues in the only ways that they could. The first was by making more and more cotton. They forced enslaved people to achieve an incredible intensity of labor, developed new kinds of seed, and expanded their acreage, but the increase in cotton production (which rose from 600 million pounds in 1837 to two billion in 1859) was more than the market could absorb. The price remained low in most years in comparison to historic levels.

The second method of enhancing revenues was by seeking new territory, both in order to add to the land under cultivation and with the hope of provoking a new boom. Unleashing the animal spirits of speculation in new territories had almost worked before, so why not try it again by acquiring California, Cuba, Mexico, or Kansas for slavery? The result of the commitment of political capital to that end, of course, was the Civil War, in which the consequences of the long-term financial difficulties of the cotton economy played a major role in Southern defeat.

Financial innovation in the 1820s and 1830s thus had massive, unforeseen, and often ironic consequences. But they were consequences in the “real” economy. Of course, there is something magical, fictitious, and strange about commodifying houses, land, and most of all, human beings. Each of those things has its own claim to being treated as something unique, with moral rights. The house acquires extra-financial value from the lives that are lived in it and which turn it into a home. Its market value depends, as well, on the domestic and family ideologies that “invest” it with more value than wood, stone, and skillful carpentry alone can supply. The land, still more immovable than the house, teems with claims, both human and non-human, historical and ecological. The securitization of a human is far more offensive still to our moral sensibilities, turning persons into numbers and paper bonds, and so dividing them up and recombining them by legislative fiat that you can carry them across the ocean in suitcases and sell them to people who profess their support for emancipation. If that isn’t fiction, then I don’t know what is. And yet in the end the reverberations set off by the leveraging of slavery’s inequities into further equity for those who exploited them were what brought the structure of real-life slavery crashing down.

Further reading

The records of Jacob Bieller and the people he brought to northeast Louisiana can be found in the Alonzo Snyder Papers at the Hill Library of Louisiana State University. Another excellent primary source that illuminates the issues discussed in this article is the R.C. Ballard Papers, located in the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina. A recent book that looks at the aftereffects of Andrew Jackson’s victory over the Second Bank of the United States is R.H. Kilbourne, Slave Agriculture and Financial Markets in Antebellum America: The Bank of the United States in Mississippi, 1831-1852 (London, 2006.) Kilbourne argues that the fall of the Bank made the ultimate calamity of 1837 inevitable.

A recent award-winning dissertation by Jessica Lepler—”1837: Anatomy of a Panic,” (Ph.D. Diss., Brandeis University, 2007)—recreates the collapse of the international economy. Perhaps the most significant book in recent years about world history on the grand scale is Kenneth Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World-Economy (Princeton, 2000), which argues that “ghost acres” of southwestern cotton fields enabled Europe to break out of the “resource cul-de-sac” that trapped the Chinese economy before it could reach what scholars used to call the takeoff point of modernization.

Finally, an excellent introduction to the way that the economic profession has, over the past fifty years, increasingly hidden from the investigation of historical issues like panics and crises in the “utopian economics” of simple models and free-market panaceas is John Cassidy, How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities (New York, 2009).

This article originally appeared in issue 10.3 (April, 2010).

Edward E. Baptist is Associate Professor of History at Cornell University. He is writing a book on how the expansion of slavery in the nineteenth century shaped African America, the United States, and the world.