Historians slip easily into categorical thinking. We assign a group or a trend to a category, such as “pirate” or “puritan,” and then all too often we let that well-worn category do the work of analysis. Designating an individual a pirate bestows motives and perspectives, creating a shortcut to deeper understanding. That ubiquitous (and in American historiography nearly meaningless) category of “puritan” covers a multitude of religious inclinations and explains numerous aspects of human existence, from childrearing to politics. Categories allow us to gloss over context and, more importantly, over gaps in evidence. When we have few sources, assigning a category automatically fills in silences and suggests explanations consistent with the particular group or movement. In this era of click-bait headlines and little time to settle in with a complicated and nuanced book (not to mention pressures to publish), categories offer a quick way to make sense of complex phenomena.

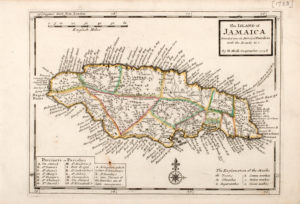

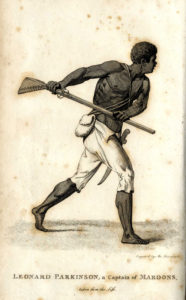

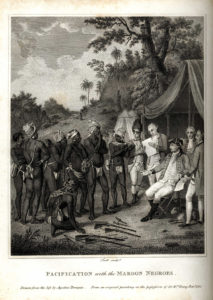

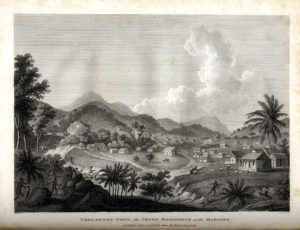

Maroonage represents a case in point: a widespread but only sporadically documentable historical trend, the category of maroon invokes a host of historical specificities. Maroons created independent enclaves of formerly enslaved people and eventually their children, away from and beyond the control of their masters. The Spanish who first confronted and named such a population labeled these communities of escaped slaves “cimarróns,” a term for domesticated cattle that had escaped to live feral in the woods or mountains. The English employed a variation of the word later when they encountered such communities in the Americas. Maroonage arose in locations where geography cooperated, flourishing in topography that granted runaways places not only to hide but to carve out permanent habitations away from their former masters. They emerged on larger islands or the South American mainland where inaccessible retreats sheltered organized enclaves of former slaves. They sustained themselves by growing their own food crops, culling semi-feral livestock, and stealing from the plantations where they had once been held in bondage. They offered haven to later runaways, thereby augmenting their populations; on occasion in Jamaica and elsewhere, they agreed with colonial authorities to return fleeing slaves in exchange for being left alone. Maroonage provided numerous Africans and their descendants an opportunity to live independent of slave regimes. Before the dramatic success of the Haitian Revolution, maroons enjoyed the best hope of African autonomy and self-determination in the Americas. Historians today find the category maroon infinitely appealing, a reversal of the discomfort and confusion with which European imperialists viewed them at the time.

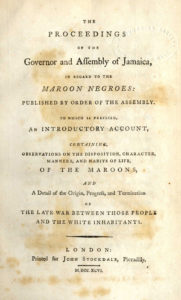

The seductiveness of this category and of categorical thinking generally has shaped the standard narrative of the origins of the Jamaica maroons, one of the best known cases of maroonage in the Caribbean. Their oft-repeated story dates their origins from the English invasion of the island in 1655. In the prevailing account, the invasion granted the island’s slaves an opportunity to flee their Spanish masters and establish the first independent maroon communities in the Jamaican mountains. In doing so, they successfully removed themselves from the slave system, forming autonomous enclaves free of both colonial and imperial authority. The Jamaica maroons persisted for over a century and successfully fought off imperial forces on numerous occasions. Finally in 1796, victorious British authorities demanded that they leave the island en masse. Despite the eighteenth-century order to leave, maroons persist in Jamaica to this day, and many others retained their identity in diasporic movements to Nova Scotia and later West Africa.

This narrative of Jamaica maroonage arising in the aftermath of the English invasion, while highly serviceable, obscures the origins of the autonomous African communities that organized in the Jamaican hinterland. The first independent enclaves were not runaway slaves but rather refugees. They came together in the mountains during an ongoing guerrilla war that pitted the island’s residents under Spanish rule against the newly arrived English invaders. Not classic runaway maroons, they constituted a community of refugees of mixed status (both enslaved and free) who together chose a separate existence in a context of warfare, conquest, and potential exile. Among the assortment of Jamaicans who fled to the interior, those who chose to reside there permanently and peaceably withdrew from the war between Spanish and English forces on the island. They opted out of moving to Cuba, where they would have taken up a social status (whether slave or free) in accordance with that which they had held in Jamaica before the invaders disturbed them. Instead, they chose to fashion a new life of subsistence and autonomy away from both English and Spanish colonists. Their decision was collective rather than individual, and the options they had differed from those available to runaway slaves. By consigning their experience to the category of maroon, we assume we know their identity (former slaves) and goals (autonomous living separate from their masters) even in the absence of definitive evidence.

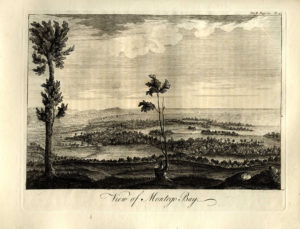

The men, women and children who erected villages in the isolated reaches of Jamaica did so within a context of warfare and displacement. When the English invaded Jamaica, virtually all the residents of the island fled. Initially everyone ran from the main town of Santiago de la Vega, taking their valuables with them. They had been through this drill before: bands of raiders arrived, at irregular intervals, intruding briefly in search of wealth and food and water to resupply their ships. Later, when the population knew that the invaders intended the permanent capture of the island, almost everyone withdrew farther into the mountains rather than accept the terms of the treaty they were offered.

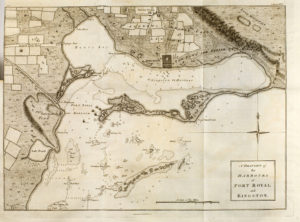

An invasion changed the situation dramatically, forcing the islanders to consider a new future very different from the lives they had lived on Jamaica. The English terms granted European colonists exile to an unnamed Spanish American territory, with transportation provided compliments of the English navy. A handful took that option, becoming wartime refugees, dumped on another population and dependent on the aid it offered. The English hoped that non-Spanish residents would throw their lot in with the invaders. The conquering army also ordered “that all the slaves, negroes and others be ordered by their masters to appear [at a designated meeting place and time] . . . to hear and understand favours and acts of grace that will be told them concerning their freedom.” Expecting these subaltern populations to greet the English as liberators, the army commanders declined to spell out the details of this offer until the meeting. But the African-descended residents chose not to take their chances on the English. This refusal stunned the English, who were aghast when not one slave appeared at the meeting place. With the small resident population—a mix of Spanish, Indian and African—scattered in the inaccessible interior and the English army encamped around Santiago de la Vega (today’s Spanish Town), the scene was set for a five-year-long guerrilla war. The resistance would be fought under the command of a Spaniard, Cristoval Ysassi, whom Philip IV eventually named governor of the island (with instructions to retake it from the English).

At this moment, everyone who had fled before the invaders faced choices: to fight in the resistance and try to reclaim the island; to surrender to the English and accept whatever treatment they meted out; or to slip away from Jamaica without English assistance. Rejecting all those options, some eventually decided to create another future, withdrawing from all European hostilities while remaining in Jamaica. Their process in coming to that decision cannot be documented, but the broad outlines of their lives can be understood. The Africans living in Jamaica when the English arrived were a mix of free and enslaved individuals. Most had been born on the island or had lived there for decades, spoke Spanish, and worshipped in the island’s Catholic church. Their language skills and high level of acculturation prompted the English invariably to refer to them as “Spanish Negroes,” distinguishing them from Africans who arrived as part of the invasion force or subsequently. Joining with the fleeing Spanish women, children, and elderly, some African refugees slipped away in small boats to Cuba. In doing so, they accepted that their status in Jamaica would carry over to Cuba, and there they would live in a Spanish community as an enslaved or free person, as they had done in Jamaica. Of those who stayed in Jamaica, some fought alongside the Spanish against the English. Others chose to strike out on their own; this group established the first isolated African settlements in the interior, as early as February 1656, some ten months after the English landed. These were not runaway slaves, but rather refugees (both slave and free) pursuing their own strategy against the invaders and eventually in defiance of the authority of Ysassi. Their withdrawal departs from the usual maroon narrative at various points, but especially in that they made that choice collectively. As opposed to runaway slaves—who struck out for freedom alone or in small groups—these individuals gathered as a sizeable group. Their joint decision created the communities they formed and an alternate future for themselves and their children in one dramatic moment.

Both the Spanish and the English were astonished when they realized that some of the refugees had opted out of their struggle altogether to chart their own, separate path. Ysassi, commanding the Spanish resistance, claimed that all the Africans were answerable to him and fighting the English under his command. Yet when the English officer Kempo Sybada, a multilingual Frisian man, happened upon a mounted African, he denied Ysassi’s version of events and claimed complete autonomy for his community. His appears to have been one of a number of independent enclaves of Spanish speaking, predominantly African individuals that coalesced on Jamaica in this period. They came together out of the refugee population and refused to return to slavery or to their lives within Spanish colonial society. Distrusting the English invaders, they created lives away from European colonizers, imperial rivalries, and a world of slavery.

One of these communities would eventually be forced into a relationship with the English government, and we can see through that outcome how it prized its autonomy and self-determination. This connection was forged only after an English party located a village in Lluidas Vale, and threatened to burn its extensive garden crop unless it would help extirpate the Spanish forces on the island. Under the leadership of Juan de Bola, it did so, playing the pivotal role in ending the guerrilla war. After the remaining Spanish departed from the island, de Bola’s community agreed with the English that they would live independently under their own leaders, but would contribute to the English colonial undertaking by serving in the militia (again, under their own officers).

At least in the short term, their deal with the English held. De Bola died in an ambush set by another “Spanish Negro” leader whose community the militia sought to locate and bring under English authority. He and other community leaders received (or regained) houses in Santiago de la Vega, which allowed them to move back and forth between the Vale where the community was centered and the town where their interactions with the English occurred. Far from a case of maroonage, their status represented a different strategy for maintaining freedom and some autonomy under colonial rule.

Other communities—never so unfortunate as to be discovered by the English army—maintained the independent existence they initially chose. At least one other community (and possibly two) remained utterly independent and, despite efforts of the English (aided by de Bola’s troops) to subdue them, they continued as autonomous entities within Jamaica. With similar refugee origins, they presumably became the basis of a future maroon enclave, augmented by increasing numbers of runaways after the English began importing enslaved Africans and Indians. No trace remains to help us understand the transition from the Spanish-speaking refugee communities to a population intermixed with individuals born elsewhere who fled Jamaican slavery. We can only imagine how the refugees and their descendants responded to newly arrived enslaved Africans, people who were unlikely to speak Spanish and who came into the Jamaican interior along a markedly different personal pathway. Out of this complex mix of backgrounds—refugee and runaway—Jamaica’s maroon communities emerged.

Refugee encampments, though they do not conform to the usual narratives of fugitive slaves or outright rebellion, represent another form of resistance. Refugees created autonomous villages and offered another way for Africans in the Atlantic world to seize opportunities to forge a life of their own making. In this case they carved out a space between warring imperial forces, seeing their opportunity to strike out for freedom as a group. Their community formed in an instant—not through a slow accretion of runaways—and they brought to it shared language, culture, and a collective past. Depositing all independent African enclaves into the familiar category of runaway slave maroons reduces the range of African experiences of freedom and struggle in the Americas.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Marisa Fuentes for urging me to write this history in a short and accessible form.

Further Reading

The most comprehensive account of the Jamaica maroons remains Mavis C. Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 1655-1796: A History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal (Granby, Mass., 1988). An interesting literary perspective can be found in Cynthia James’s The Maroon Narrative: Caribbean Literature in English across Boundaries, Ethnicities, and Centuries, Studies in Caribbean Literature (Portsmouth, N.H., 2002), 11-14. For treaties between slave-owning authorities and maroons that included provisions for the return of runaways, see Alvin O. Thompson, Flight to Freedom: African Runaways and Maroons in the Americas (Jamaica, 2006), 208-11. My book, The English Conquest of Jamaica: Oliver Cromwell’s Bid for Empire (Cambridge, Mass., 2017), reconsiders the English invasion and the resultant refugee exodus and guerrilla war, among other topics. The Anglo-Spanish treaty, negotiated but never adopted (and quoted above), can be found in “Articles of Capitulation at the Conquest of Jamaica, 1655,” Jamaica Historical Review I:1 (1945): 114-15.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.4 (Summer, 2017).

Carla Gardina Pestana is professor and Joyce Appleby Endowed Chair of America in the World at UCLA. She writes on religion, empire, and the Atlantic world; her most recent book, published by Belknap, is The English Conquest of Jamaica: Oliver Cromwell’s Bid for Empire.