On July 4, across the United States of America, hot dogs sizzle on barbeques. Marching bands trumpet the anniversary of American independence. Fireworks fill the night sky from coast to coast. Independence Day is hard to miss. It is bright. It is loud.

Not so in my sleepy New England hometown of Exeter, New Hampshire. No trumpets or firecrackers here. Tumbleweeds might as well be rolling down the streets of New Hampshire’s revolutionary-era capital on the nation’s birthday. Exonians are not unpatriotic; they just like historical accuracy. Here, the independence celebration is keyed not to the adoption of the text of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776, but to the arrival of these words in Exeter. Check back with us in about two weeks.

It is July 16, 2016. The boom of canons has alerted the town to gather on Water Street between Folsom Tavern and Stillwells, an ice cream shop. The crowd is a motley crew. Some people hold iPhones; others hold ten-pound flint-lock muskets. There are folks dressed in wicking Under Armour, and others in wool uniforms. Children lose their grips on red “Exeter Historical Society” balloons, and a blacksmith stokes a portable forge preparing to make hand-wrought nails. At 11 a.m., the sounds of a fife and drum corps approach, followed by a thin man on a horse. John Taylor Gilman is making his entrance.

Gilman dismounts and ascends the hill to the platform outside the Ladd-Gilman House (now the American Independence Museum). He waits his turn. First, the museum’s executive director and then a representative of the town of Exeter’s Board of Selectmen address the crowd. A message from New Hampshire’s governor is read. Finally, George Washington steps up to the microphone. Washington will be spending the day in the tavern museum schmoozing with the hoi polloi as they drink a local brewery’s take on eighteenth-century beer. The nation’s first president introduces Gilman. On July 16, 1776, Gilman was the twenty-two-year-old son of New Hampshire’s revolutionary treasurer. He would have a lifelong career in New Hampshire state politics, but on that day, legend has it, he performed a nation-making piece of oratory as he read to the citizens of New Hampshire the hot-off-the-presses Declaration of Independence.

Gilman unfurls a large single-sided piece of paper and begins to read, “When in the course of human events …” As Gilman reads every one of the Declaration’s 1,320 words, the gathered crowd listens in silence for what, to twenty-first-century ears, seems like an eternity. After a few minutes, there is some noticeable pushing and shoving as a new group of listeners arrives. They are wearing a variety of eighteenth-century British military uniforms. Gilman reads the line, “The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations.” Suddenly, the new arrivals start shouting “boo” and “traitor.” Ragtag militiamen respond to the heckling with loud cries of “huzzah.” Their camp followers—women and children—join in the shouting match. The patriots and the loyalists (including a lone Hessian) begin to square off. They are scheduled to fight a mock battle later in the afternoon. But right now, as Gilman reaches the end of the document, “we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor,” the crowds line up to enter the un-air-conditioned museum.

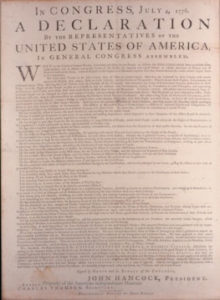

This is the beginning of Exeter’s American Independence Festival, which in addition to a schedule of activities, is the once-a-year opportunity for the public to view the American Independence Museum’s most valuable holding, a Dunlap broadside. This document is the raison d’être of the museum, the festival, and Exeter’s delayed celebration of American independence. So what is it?

The Dunlap Broadside and the Society of the Cincinnati

In Philadelphia on July 2, 1776, the delegates to the Continental Congress voted to declare independence from Great Britain. On July 3, John Adams wrote, “The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival.” He was close. The next day, Congress voted to adopt the words we now know as the Declaration of Independence. The iconic endorsing signatures of all the delegates would be inked a month later, yet the text of the Declaration itself was so meaningful that July 4 became the nation’s birthday.

For these words to spread, however, they needed to take material form; they needed to be printed. That evening, after the votes were tallied and the Declaration adopted, printer John Dunlap was tasked with setting the type and producing approximately 200 copies of the text. His version involved no swirls of calligraphy, just simple seriffed letters printed on a single side. Before all the ink was fully dry, John Hancock, president of the Congress, sent these copies to the colonial legislatures, committees of safety, and military leaders. The broadsides traveled to their destinations via express riders moving at the speed of horse hooves. It took nearly two weeks to get to New Hampshire, the northernmost rebelling colony. As a result, Exeter’s residents thought they were King George’s subjects twelve days longer than Philadelphians. In a letter to Hancock written at Exeter on July 16, 1776, the New Hampshire Committee of Safety acknowledged receipt of its copy and reported, “Such a Declaration was what they most Ardently wished for. And I Verily believe it will be Received with great Satisfaction, Throughout this Colony, a very few Individuals excepted.”

In reference to the printer’s name and the poster-like format, the physical documents printed during this first edition of America’s most foundational text have become known as “Dunlap broadsides.” In 2017, only twenty-six copies are known to survive. These rare sheets of old paper have been found in all sorts of unusual places. One copy was discovered in an unopened crate in a bookstore. Another was being used to wrap a bundle of other papers in an attic. In 1989, one was found behind a painting bought at a flea market for four dollars. In 1991, it sold for $2.42 million; in 2000, it was sold again for an unprecedented $8.14 million. Invaluable words, yes. Priceless paper, no. Dunlap broadsides command prices, huge prices. They are very valuable commodities.

The Dunlap broadside (the broadside) on display during Exeter’s American Independence Festival was “discovered” in 1985 in the attic of the Ladd-Gilman House. The house was built in the early eighteenth century and was the home of the politically prominent Gilman family. During the Revolutionary War when Exeter was the state capital and a booming inland seaport, the house served as the treasury. In 1902, the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Hampshire acquired the house from the Gilman family. The society, a hereditary organization composed of the eldest male descendants of New Hampshire’s commissioned officers who served in the Continental Army and Navy, named it Cincinnati Memorial Hall. In this clubhouse, members gathered for meetings and brought with them artifacts from the revolutionary era for a kind of grown-up show-and-tell. Some of these objects had been passed down in their families; others were acquired over time. The collection grew: political cartoons, swords, furniture, rare books, original drafts of the Constitution complete with handwritten notes, an eighteenth-century purple heart, and portraits of revolutionary leaders by famous artists. Despite the value of the items at Cincinnati Memorial Hall, the collection was unorganized and record-keeping haphazard. The society, however, knew it owned valuable artifacts. In 1985, the society hired a local electrician to install a security system, which required attic access. Local lore suggests that the electrician’s assistant “discovered” the broadside in a stack of old newspapers serving as insulation. The society, in turn, argues that the broadside was “rediscovered” by a member during an inventory of the items stored in the attic inspired by the electrician’s need for access. Regardless of who should be credited with finding the document, it quickly became clear that this piece of paper was worth quite a lot of money. By selling the broadside, the society could afford to repair and restore the rest of its collection, including the Ladd-Gilman house and Folsom Tavern.

The society had stumbled upon a bounty, or at least the members and appraisers thought so. The society reached out to leading sellers of historic documents and rare books. Most valued the broadside at around $500,000 (adjusted for inflation to 2017, that would be about $1.1 million). This is probably a low estimate given the more than $2 million sale price of the copy discovered and sold just a few years later.

The price tag, however, proved inconsequential. As the society prepared to send the broadside to auction, the state of New Hampshire intervened. It turns out that, in legal terms, the mystery of who found the broadside matters a lot less than who lost it. Did a member give it to the society during the show-and-tell meetings sometime after 1902? Or was it the original copy—the one sent to the Committee of Safety by Hancock that arrived on July 16, 1776—hidden in the attic of the state treasury? In 1776, after all, the broadside was not a rare, valuable piece of old paper; it was treason. If the Gilmans hid the broadside in their house in the 1770s, it was never theirs to convey to the society. It was technically state property. And the state of New Hampshire wanted it back.

Lawyers for the society and the state battled for five years. In 1990, they reached a deal that, among other things, required the society to transfer “its rights and interest” in the broadside and “title” to all of its other “Historical Material” to a new non-profit corporation, “which will actively operate a museum and study center of the American Revolution . . . on the Society’s historically significant properties in Exeter, New Hampshire.” The state’s goal was to keep the broadside in New Hampshire and “afford the public maximum opportunity for its viewing.” The parties agreed that by displaying the document at the new museum, “the public shall have ample opportunity to view the broadside.” Thus, the American Independence Museum was born.

The American Independence Museum and Exeter’s American Independence Festival

With the agreement with the state of New Hampshire, the broadside had transformed from the Society of the Cincinnati’s bounty to its burden. Whereas a sale might have brought money into the society, ownership came with costs. The agreement did not require the state to commit any financial support to the American Independence Museum. Running the museum was more expensive than maintaining a private clubhouse. The society became the museum’s largest donor not only in terms of its collection but also in terms of operating budget. And over time, the museum exhibited its most important artifact less and less. By far the most valuable piece of paper in Exeter if not in the entire state of New Hampshire, the broadside needed both security and preservation. The security system installed at the time of its discovery was inadequate to safeguard it. The historic Ladd-Gilman house where the museum was located could not be climate controlled. To save the valuable paper from theft, humidity, and temperature fluctuations, it was moved to a bank vault. A full-size duplicate was put on permanent display, but according to the agreement with the state, the museum still needed to provide the public with access to the original.

By the early 2000s, the museum decided that the original Dunlap broadside would only be available for public viewing during its most important annual event held every year on the third weekend in July. Exeter’s American Independence Festival, earlier called Revolutionary War Days and originally a part of the town of Exeter’s Old Home Days, was created in 1990. Although the local Chamber of Commerce and various town committees were involved, the museum’s staff turned a collection of contemporaneous programming into a single event, which aimed to draw attention and paid attendance to the museum. They used posters and printed schedules to pitch a celebration of Exeter’s revolutionary era glory. The broadside (printed to be hung like a poster) inspired a festival created by a poster.

During its twenty-seven-year history, the festival has changed a great deal. It has expanded to four days and shrunk to one. It has featured canoe rallies and clambakes, petting zoos and parades, archaeological digs and artisanal demonstrations, funnel cakes and fifes, duck races and sidewalk sales, hot air balloon demonstrations and hay rides, a giant teepee and a giant Declaration, and even the “tar and feathering” (with maple syrup) of the museum’s first director.

Four essential features, however, have been constant. First, the town of Exeter launches its fireworks display on the Saturday night (in the spirit of Yankee frugality, it enjoys a post-Fourth fireworks discount). Second, militia re-enactors convey the dependence of American independence on war (a fitting lesson from the descendants of George Washington’s military officers). Third, the text of the Declaration of Independence is performed as public oratory (John Taylor Gilman’s re-enactor has at times shared this honor with the local Boy Scout troop). And fourth, since the festival’s inception, the broadside has always been made available for public viewing. It is, after all, the reason the festival exists.

Every year numerous historical inaccuracies are incorporated into the festival (among the most glaring: no revolutionary battle was fought here, and George Washington enjoyed a meal at Folsom Tavern in 1789, not in 1776). Much of the event is historical re-enactor fantasy and fairground kitsch. Nevertheless, what makes the festival fascinating is that it actually does celebrate historical accuracy in a keenly local way.

Regardless of their geographic distance from Philadelphia, most American cities and towns celebrate Independence Day on July 4. This small New Hampshire town celebrates American independence when the king’s subjects in Exeter would have gotten the news that they had been declared American citizens. If you can ignore the microphone, Gilman’s oration of the Declaration’s poetic statements of universal rights and its long litany of royal usurpations is still powerful. After nearly two and a half centuries, the enunciation of these words commands silence, raises goose bumps, and makes eyes water. The Declaration’s text still deserves its celebration. And, the nearly two-week wait for fireworks and festivities literally brings home the power of the broadside as an object. It is a concrete reminder that the Declaration was once a material thing, ink on paper that traveled by literal horsepower. As a public history lesson, the festival historicizes “timeless” documents and our expectations of instantaneous communication. It reminds us of the roles of tyranny, force, and eloquence in the creation of the American nation.

Whether or not the document on display on July 16, 2016, is the same piece of paper that took nearly two weeks in the saddle to be delivered to Exeter on July 16, 1776, it is an original printing of the Declaration of Independence. And it was found in a small town that often feels like it exists outside history. No longer a bustling seaport, Exeter has become an academy town where elite high school students escape the world to focus on their educations. The festival reminds us that Exeter was once a more politically important place. Exonians at the festival celebrate their town’s outsized past by looking at and hearing a work of national creation that traveled a long way and a long time to get to them.

Acknowledgments

As an early American historian, I relished the novel delight of interviewing my sources for this article, and want to express my gratitude to Carol Walker Aten, Tracey McGrail, Stephen Jeffries, Bob Mitchell, Laura Martin, Victoria Su, and Emma Bray. I am also deeply indebted to several archivists: Rachel Passannante of the American Independence Museum, Barbara Rimkunas of the Exeter Historical Society, and Brian Burford of the New Hampshire State Division of Archives and Records Management.

Further Reading

For the history of the Declaration of Independence, see Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York, 1997); David Armitage, The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (Cambridge, Mass., 2007); Frederick R. Goff, The John Dunlap Broadside: The First Printing of the Declaration of Independence (Washington, 1976); and online resources based on the “Declaration Database” project at the Center for American Political Studies at Harvard University.

For the history of Exeter, see W. Jeffrey Bolster, ed., Cross-Grained & Wily Waters: A Guide to the Piscataqua Maritime Region (Portsmouth, N.H., 2002); and Barbara Rimkunas, Hidden History of Exeter (Charleston, S.C., 2014). Early histories of the town were written by Charles Henry Bell in 1876 and 1888 and are available online.

This article originally appeared in issue 18.1 (Winter, 2018).

Jessica Lepler is an associate professor of history at the University of New Hampshire. Her first book, The Many Panics of 1837: People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis, won the James H. Broussard Best First Book Prize from the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic.