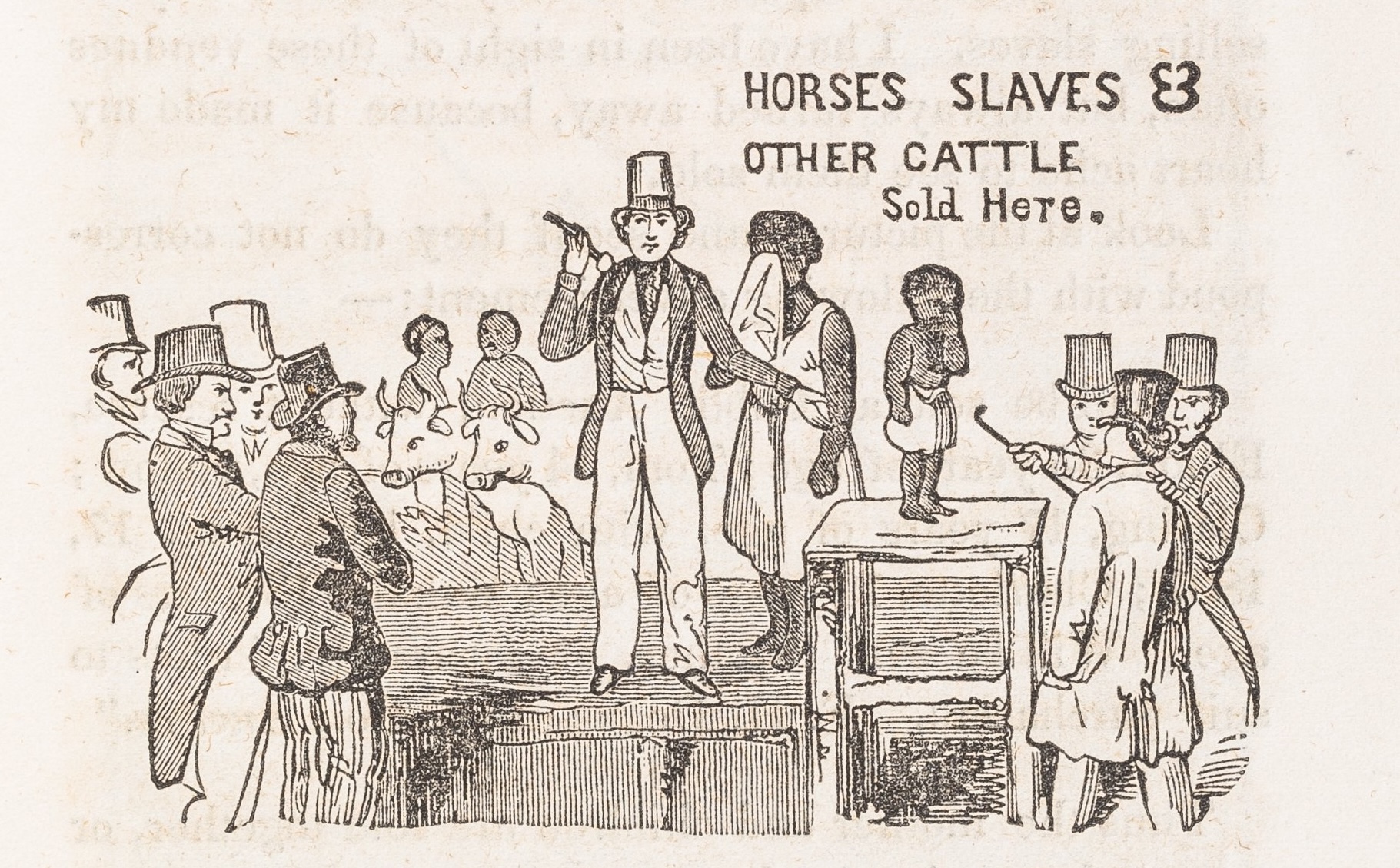

The McMurteries’ argument, on its face, seems compelling, and the Browns did not counter the facts put forward. But the Browns’ defense of their actions tells us a great deal about the conflicting legal regimes of the British Empire in the middle of the eighteenth century, as well as the ways that conflict vested authority in the marine insurance business and rendered it profitable.

The Browns justified their behavior by pointing to two sources of authority. The first was the Governor of Rhode Island. They affirmed that the vessel was “in the actual Employ” of Stephen Hopkins, “Esquire, Governor, Captain-General, and Commander in Chief” of Rhode Island. Their flag of truce was his genuine issue, they asserted, and they had the paperwork to prove it. What this meant was that the precise number of prisoners on their vessel, headed in either direction, was irrelevant—by the authority of Hopkins’ papers, they were genuine flag trucers.

The second source of authority by which the Browns defended their actions was their insurance policy itself. The Browns pointed out that their policy was a comprehensive one, which not only covered capture by British vessels, but also included a specific wartime proviso that the underwriters were not allowed to argue about the legality of capture. “The Assurers,” they pointed out, “promised to pay the Loss, without further Proof, than the said Policy; and to prevent any Dispute thereafter about the Legality of the said Insurance, they promised to pay at the usual Time without any Delay, or intention to plead the Goods were not lawful Seizures by Custom-house Officers in Providence only excepted, as by the said Policy of Insurance more fully may appear.” In other words, it was irrelevant whether or not the Browns’ activities were adjudged in the end to be legal. They had purchased an insurance policy that explicitly protected them against the inconvenience and cost of a lengthy dispute about whether their activities were legal or not. The matter was not supposed to get to law in the first place.

What would the Privy Council decide?

Britain’s Privy Council had been taking an increasing interest in commercial law over the course of the eighteenth century. Like the British admiralty courts, which operated as a distinct system, the Privy Council grappled with the colonists’ boundless enthusiasm for illegal trade, and with various legal complications brought about by the expansion of privateering. In aggregate, increasing numbers of cases appealed from the American colonial supreme courts were overturned by the Privy Council, demonstrating the Council’s newfound inclination to assert its own control over enforcement of the Navigation Acts.

This, then, seems to be a familiar story of expanding imperial authority—one of the sort that seems to prefigure the American Revolution. One might assume the Privy Council would leap at the chance to support underwriters who, in this instance, were actually trying to force merchants to adhere to a stricter interpretation of the law. To take the McMurteries’ side would seem to bolster the authority of the empire, to affirm strict interpretations of the laws of truce, to help stamp out contraband trade with the enemy, to support the privateers who helped enforce the laws of trade, and to encourage the alignment of insurance policies with British law. In short, it would seem to be a great opportunity to assert the authority of the empire over unruly traders who placed profits over loyalty.

However, matters were not so simple as a unified empire opposing conniving free traders, because the empire had many component parts and many different interests. Flag trucing was an extremely useful practice for cash-strapped colonial governments, in that it allowed them to offload expensive prisoners and recover subjects, at the price only of a private shipowner’s for-profit voyage. To support trade under flags of truce, then, was to support a prospering trade for the empire’s own colonies. The revenue produced by this trade stabilized and empowered local imperial administrators, who generally operated under a great deal of pressure.