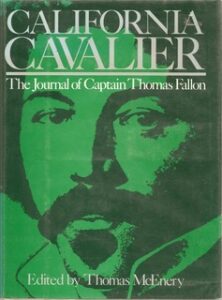

Notwithstanding the sympathetic depiction in the journal, both the stubborn facts of Fallon’s personal story and a growing demand for the untold stories of early California became major obstacles for Tom McEnery’s project to make Fallon a unifying symbol for San Jose. By the time McEnery became mayor in 1983, he had already participated in the restoration of Thomas Fallon’s and Luis Peralta’s houses. McEnery’s next plan was to restore the plaza at the heart of San Jose, and its centerpiece was to be a bronze statue of Thomas Fallon on a horse, carrying the American flag that he had raised over the Juzgado. The statue was commissioned in 1987 and was scheduled to be erected in 1990 in the central plaza of the city. It was to be the first in a series of three statues celebrating San Jose’s multicultural history, one of Thomas Fallon, the next of Luis Peralta, and the last of Saint Joseph, the city’s namesake. McEnery envisioned an educational curriculum centered on these figures that would teach San Jose students about their local history.

If McEnery had chosen Peralta as the first subject of his sculptural troika, things might have turned out differently. When news broke that the $711,000-dollar statue of Fallon was completed and on its way from an Italian foundry to San Jose, all hell broke loose. Latinx residents of the city, many of them descendants of the Californios or more recent immigrants from Mexico, saw the Fallon statue as an insult, deeply disrespectful to the cultural heritage of half of the city’s population. In response to the plan, they packed City Council meetings with protesters, picketed the proposed site of the statue, and lined up support for blocking the statue from teachers’ associations, labor organizations, and the Pueblo Unido de San Jose. Protesters’ objections to the statue were both general—the statue celebrated an “immoral war of conquest” that privileged a “white supremacist” narrative—and specific—Thomas Fallon was peculiarly undeserving of immortalization in bronze.

It hadn’t taken much research for opponents of the statue to uncover the unsavory aspects of Fallon’s character that McEnery had tried to explain away in the journal. Not only had Fallon shot my grandfather Exervier in the back, but he had cheated on and abused his own wife, resulting in divorce proceedings reported in lurid detail in the newspapers. These stories included accusations of habitual drunkenness, deceitful land dealings, and verbal and physical abuse.

It is hard to miss the irony of the last charge: Fallon had been abusive to his own wife, a woman of color. That was precisely what the fictional Fallon of the journal accused Exervier of doing. Fallon’s murder of the fur trader—“I would do it again”—was presented in the journal as an honorable act in defense of an Indigenous woman. By placing that rescue on the front page of the journal, McEnery anticipated and rebutted the charge that Fallon himself was abusive to women of color.

McEnery and San Jose historian Clyde Arbuckle did their best to counter the charges against Fallon. Arbuckle downplayed the reports of Fallon’s abusive behavior, fraudulent land dealings, and drunkenness, claiming that nineteenth-century newspaper reports had been “magnified.” McEnery insisted that his “one objective regarding Fallon and the other planned commemorative statues was to achieve an accurate portrayal of past history.” How, he asked, could Fallon represent oppressive white conquerors when he didn’t even arrive in San Jose until after Mexican troops withdrew from the city? McEnery also emphasized Fallon’s strong friendships with Luis Peralta and other Californios, declaring that “opposition to the statue . . . was fomented by opportunists who ignored the fact that Fallon was a positive symbol of the joining of the American and Californio communities.”

For opponents, “accuracy” was not the point. Once Fallon had been enshrined in bronze, he stood for all settler colonialists and was accountable for their acts of dispossession, violence, and oppression.

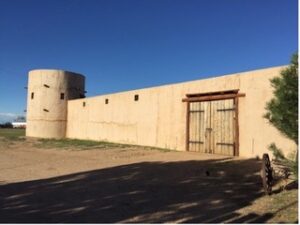

Contentious council meetings, protests, and letters to the editor continued for months, forcing City Hall to delay erecting the statue. In a conciliatory move, Mayor McEnery appointed a Historic Art Advisory Council to come up with a plan of action. The council decided that before the Fallon statue could be displayed, the city would commission and erect four other pieces of art that better reflected the city’s diversity. One by one over the next decade these works of art appeared throughout San Jose. During all that time, Fallon and his horse were moldering in an Oakland storage facility, at a cost exceeding $200,000.

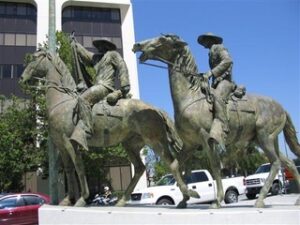

In 1999, after the last of the four art-committee-planned sculptures was erected, modern San Jose’s first Latino mayor, Ron Gonzalez, decided to end Fallon’s exile. Removing the statue from storage, he placed it in an obscure pocket park in a run-down section of town. Picketers still appeared at the dedication, but it was a relatively tame affair. In acknowledgment of the controversy, the art council placed a plaque alongside the statue that briefly summarized the views of both supporters and opponents, concluding with the bland understatement: “This artwork is a reminder that a community’s historic events can be interpreted in many ways, depending upon one’s perspective.” Fallon’s statue was on display, but so were the four more diverse sculptures, providing a balance in artistic representations of the past that city leaders hoped would mollify protesters.

The approach worked for a time; the statue attracted neither protests nor much attention from 1999 to 2020. Then two developments reignited the controversy: the revitalization of the area around the statue, making it much more visible; and the nationwide reckoning with police brutality and white supremacy in the aftermath of the May 2020 murder of George Floyd. Indigenous, Latinx, Asian, and other groups with histories of oppression identified with the revitalized Black Lives Matter movement, and Fallon’s statue became a target once again. Every week protesters doused it with red paint symbolizing “the blood on Fallon’s hands during the Mexican American War,” spray painted words like “genocide” across it, or attempted to burn it. While most protests focused on the statue as “a deeply offensive example of systemic racism,” some of the more personal charges also resurfaced: Fallon was a murderer, a wife-beater, a land swindler, the very worst sort of white settler colonialist.

Costs for cleaning and protecting the statue piled up along with protests. By 2021, San Jose’s government had become much more representative of its diverse population; when Latina City Council members Maya Esparza and Sylvia Arenas joined those in the community calling for the statue’s removal, they met little opposition. After two traumatic years of isolation, political division, and reckoning with racism, city leaders wanted a more unifying message. San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo wrote, “Since this is a public work of art, in a prominent, public place, we should ask ourselves whether it’s really worth tormenting our neighbors with a daily reminder of an image that they view as oppressive.” In November of 2021, the City Council voted unanimously to remove the statue and return it to storage.

* * *

The Fallon statue controversy revolved around competing ways of remembering the history of San Jose and clashing versions of Thomas Fallon’s life. The history of San Jose that Tom McEnery promoted was a “master narrative,” which, as Daniel Richter defines it, is a story that explains “who a people are, where they have been, and what they hope to be.” It is “a serious, essentially mythic business of defining group identity.”