After I read the book, I remember asking a foreign-born friend about Mason & Dixon. I figured she’d be enthusiastic since she was doing her Ph.D. in the history of early astronomical science. “I don’t identify with the culture,” she told me. I was appalled by the response. Exactly what culture did she not identify with? American culture? Pynchon’s book takes place before there was a United States.

In retrospect, I kind of see what she meant. Pynchon is an American novelist in every sense but you wouldn’t recommend him to a foreign visitor. The intimate struggles at the core of our national being don’t interest him in the way they did Melville or Faulkner or Roth or Morrison. In Pynchon’s America, most of us are busy buying muscle cars and steak knives while a few outliers, inclined to plumb the nation’s deeper realms, face a terrifying epistemological void.

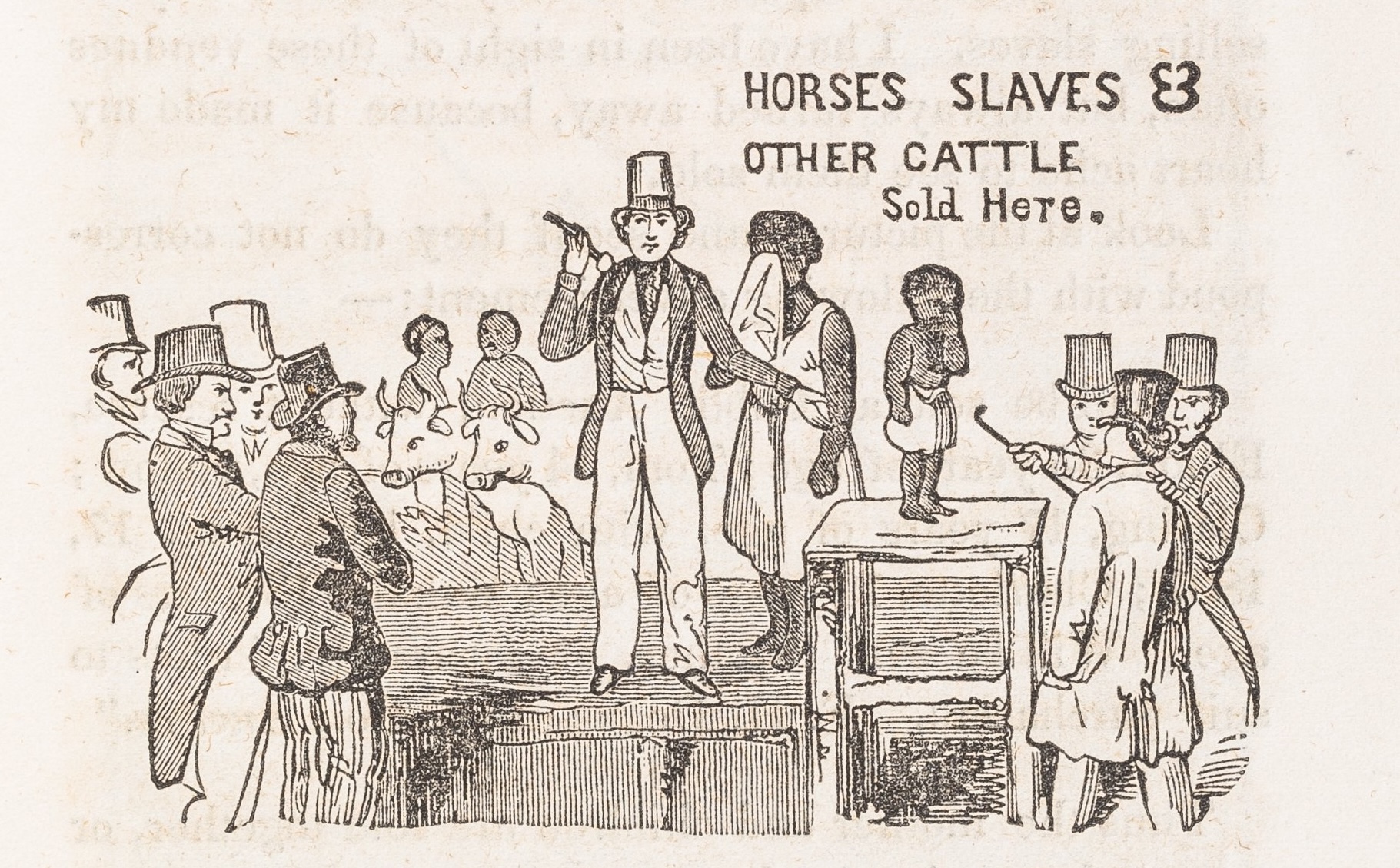

Pynchon’s Mason and Dixon embody neither of these Pynchonian archetypes—they inhabit a world of producers rather than consumers. It is a starkly Newtonian world. There is light and there is dark. There are lines and there are circles. There are statements of truth and statements of abject fiction. But there is also a shadowy netherworld, not quite the dark web of Pynchon’s modern America, but something altogether more creepy.

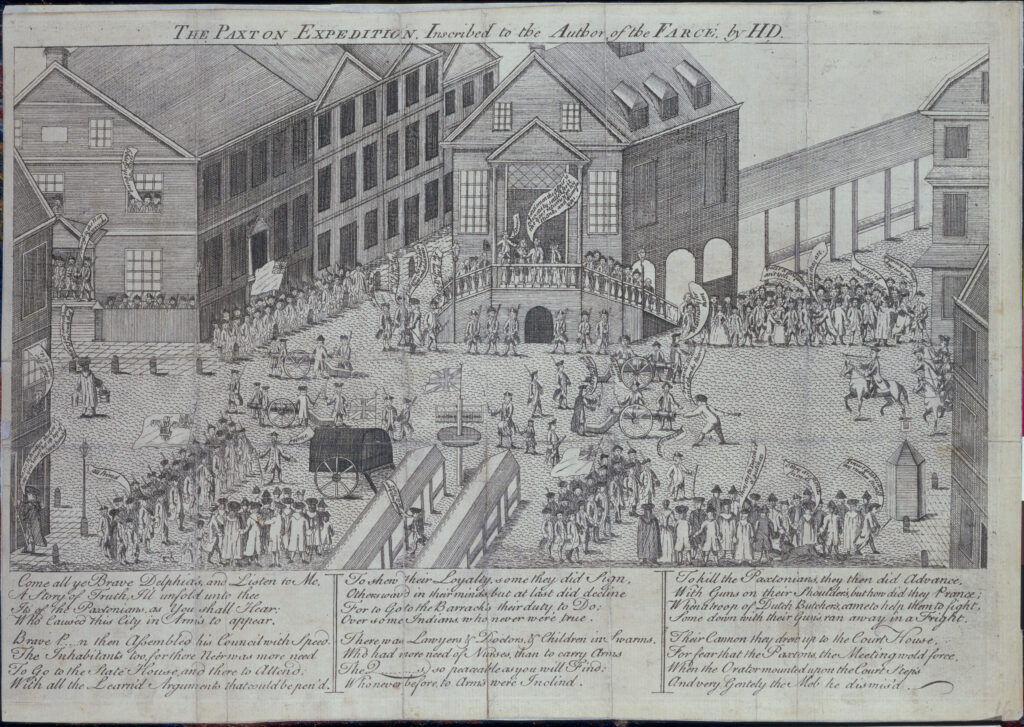

Reverend Wicks Cherrycoke, Mason & Dixon’s narrator, recalls a strange assemblage of travelers journeying in a Jesuit coach, “a Conveyance, wherein the inside is quite noticeably larger than the outside.” He joined the travelers before the French and Indian War, somewhere near the meandering waters of the lower-Susquehanna and the frontier outpost of Lancaster. One of the travelers, the “jovial Gamer” Mr. Edgewise, is heard to say,

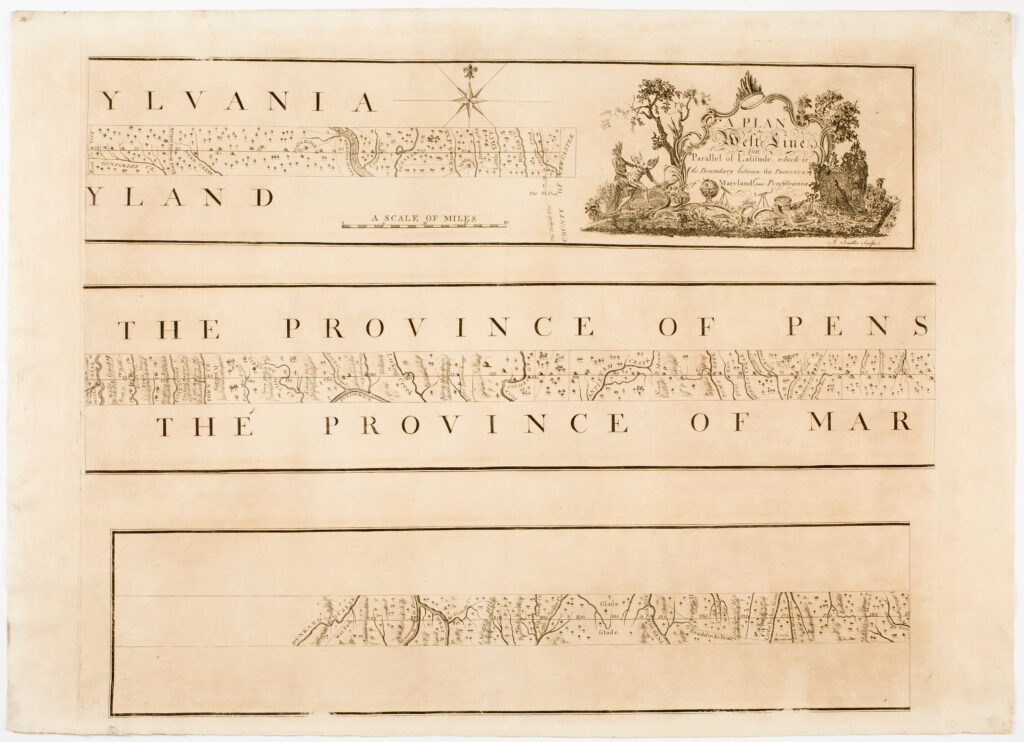

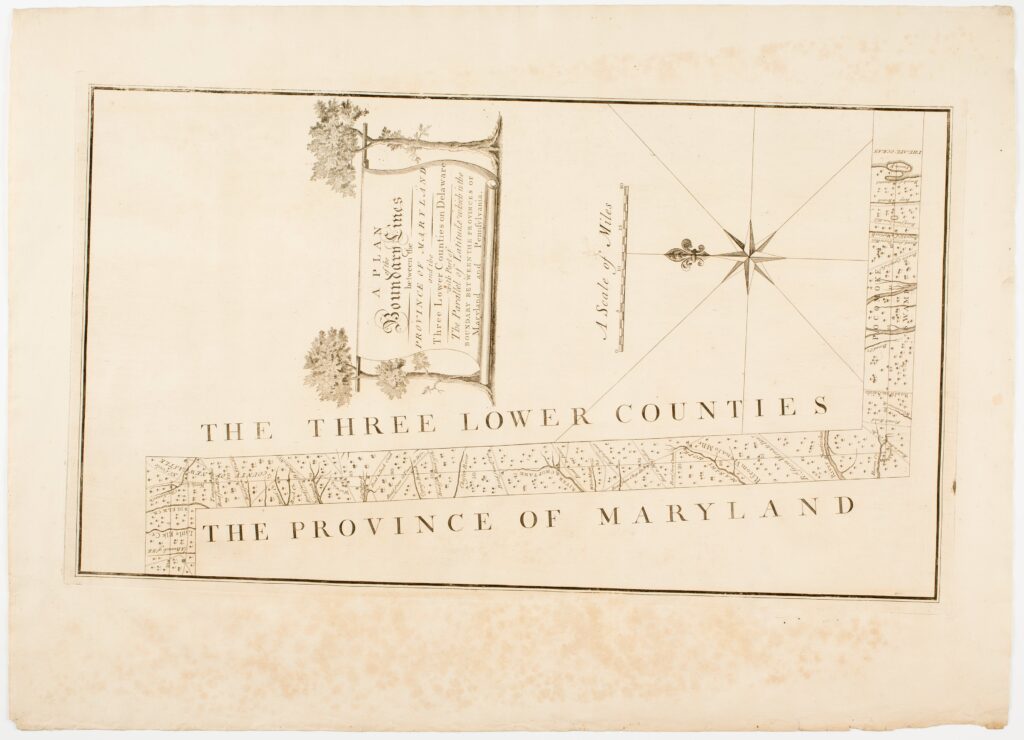

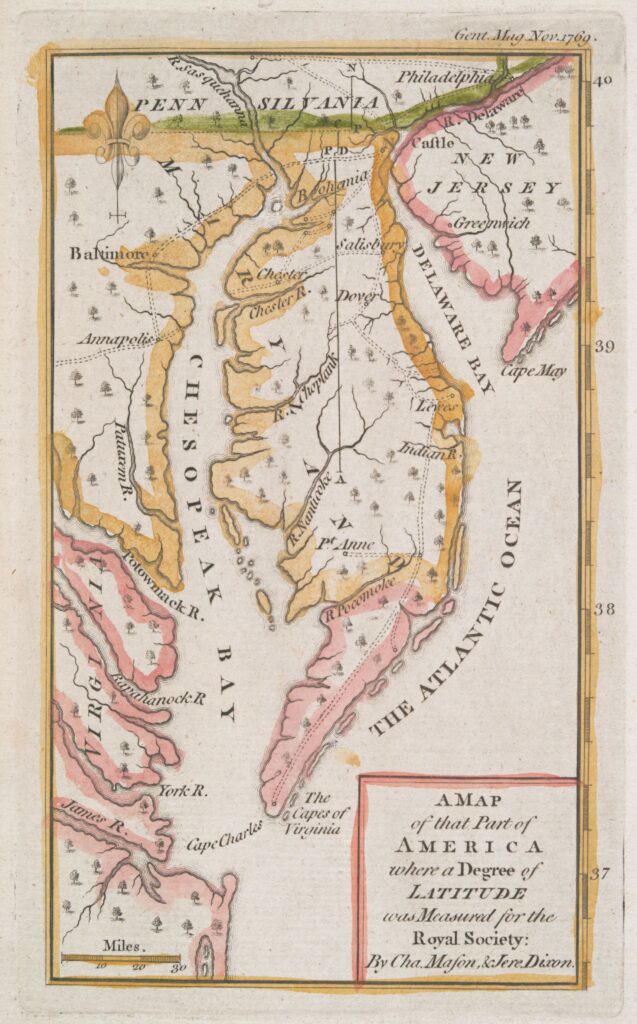

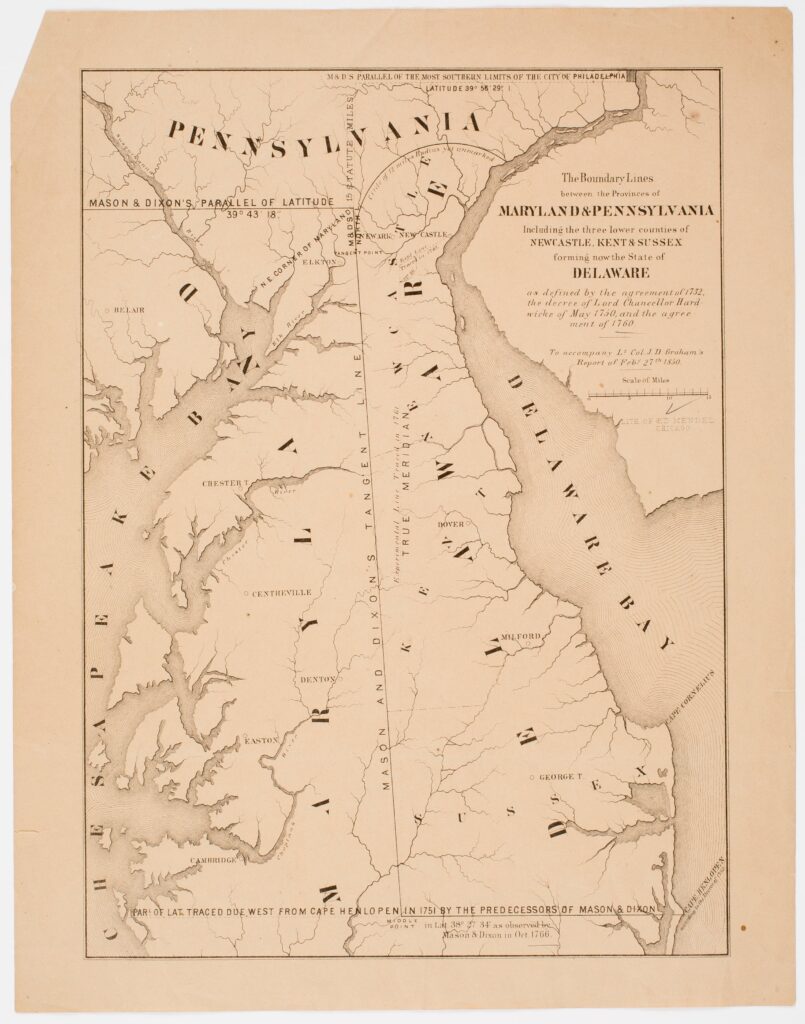

We have passed, tho’ without comment, out of the zone of influence of the western mountains, and into that of the Chesapeake,—as there exists no “Maryland” beyond an Abstraction, a Frame of right lines drawn to enclose and square off the great Bay in its unimagin’d Fecundity, its shoreline tending to Infinite Length, ultimately unmappable,—no more, to be fair, than there exists any “Pennsylvania” but a chronicle of Frauds committed serially against the Indians dwelling there, check’d only by the Ambitions of other Colonies to north and east.

The boundary lines preceding Mason and Dixon, everybody knows, were a sham. What’s to follow, despite the weighty authority of astronomical science, will be no better.