If all this trudging back and forth between various offices, houses, and jails sounds less like heroic activism to you and more like a Kafkaesque bureaucratic nightmare, that is my point. Slogging for miles through slush and snow in the dark and the cold, following the legal processes, trying to force public servants to do their jobs, knowing the law, understanding court procedures—this is what it was often like to actively work against slavery. Infuriating, complicated, annoying, tedious.

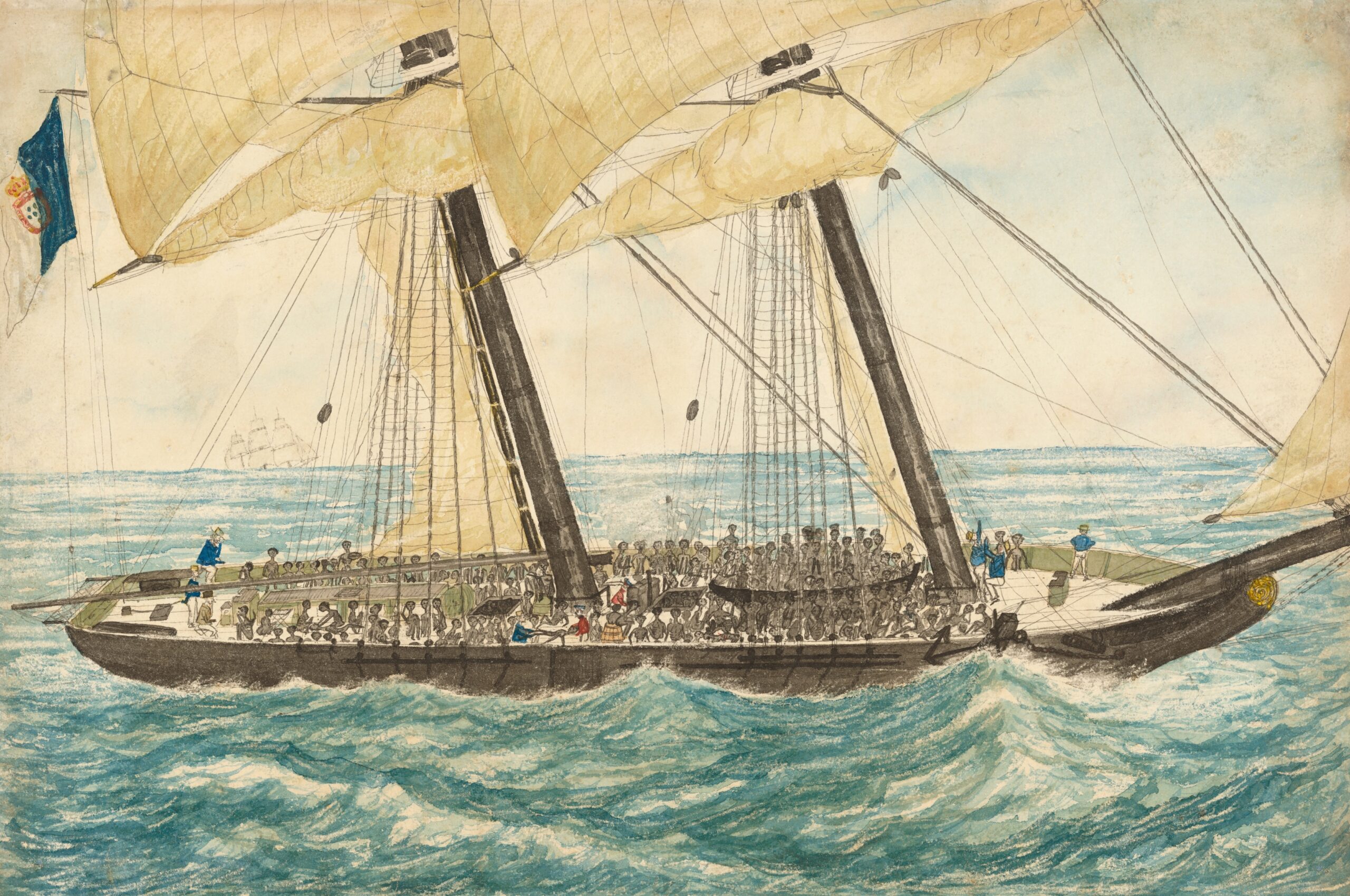

This brand of heroism can be hard to talk about, especially in public-facing histories, which must be not only accurate but entertaining. Sometimes, it seems as if historians work to make the work of activism seem as dramatic and colorful as possible. But it is important, too, to understand that much practical abolitionist work probably didn’t feel heroic or historical or impressive at all. Much of it was the frustrating and incomplete result of sheer doggedness. The story of the brig Brilliante reminds us that history is not just made by firsts: It’s made by repetitive efforts, too. Ruggles’ tedious brand of heroism serves to remind us of the thousands of other acts of quotidian courage performed by thousands of forgotten people, who had jobs and small businesses and children, but who were nonetheless willing to spend hours and hours walking through filthy snow.

Further Reading:

Primary sources:

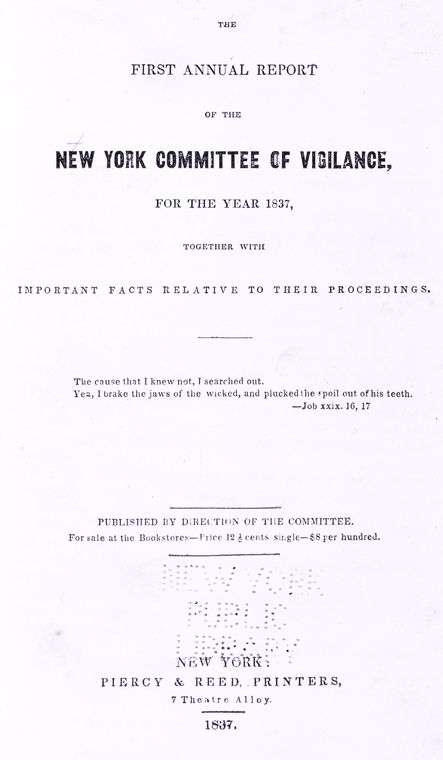

David Ruggles, The First Annual Report of the New York Committee of Vigilance, for the Year 1837, Together With Important Facts Relative to Their Proceedings (New York: Piercy & Reed, 1837), https://reader.library.cornell.edu/docviewer/digital?id=may839002#mode/2up.

David Ruggles, The Mirror of Liberty, vol. 1, no. 1 (New York: David Ruggles, 1838).

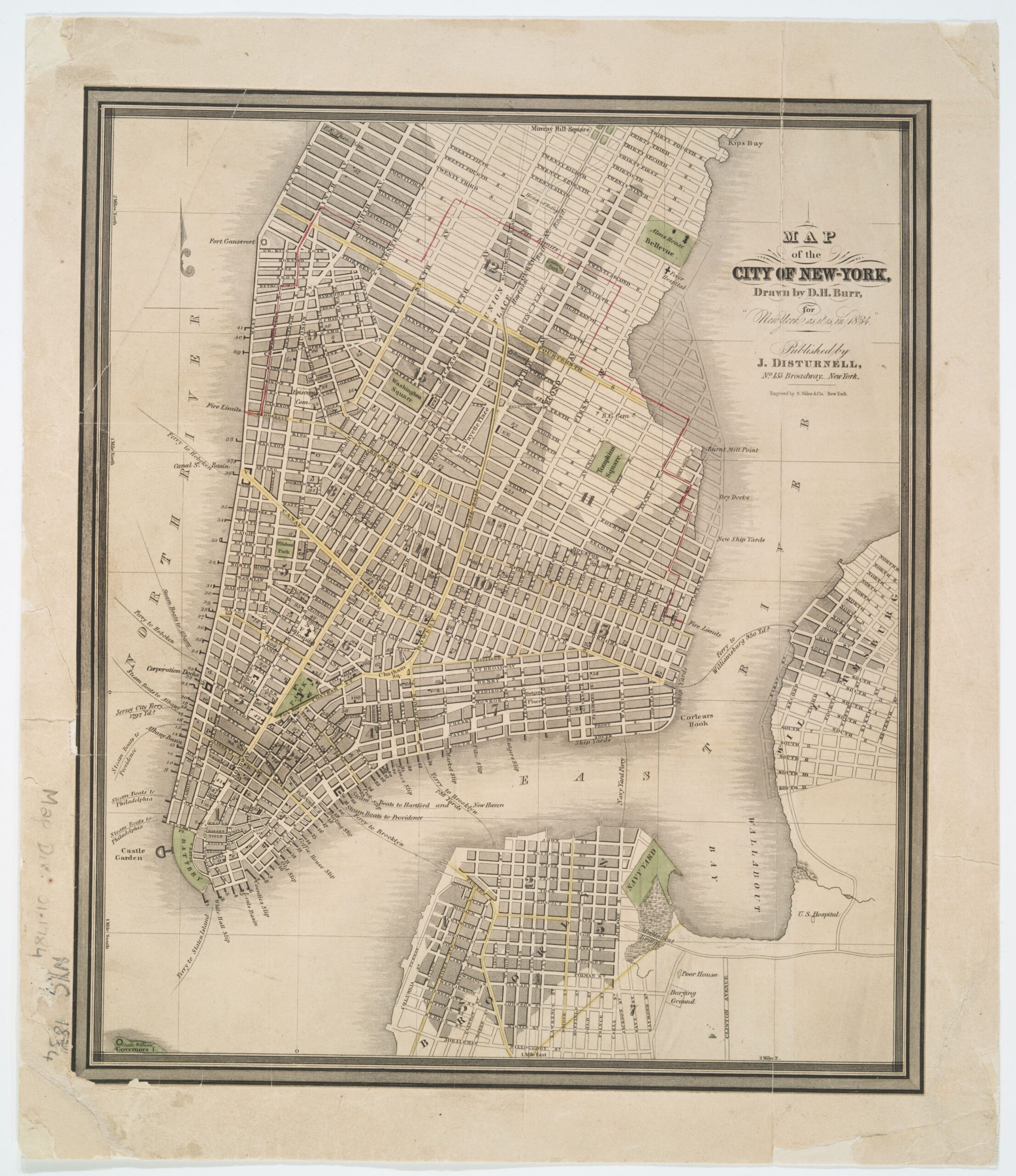

Edwin Williams and John Disturnell, New York as it is, in 1837 (New York: J. Dusturnell, 1837).

Frank M. O’Brien, The Story of the Sun (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1918).

Laws Relative to Slaves and Servants, Passed by the Legislature of New-York, March 31st, 1817. Together with Extracts from the Laws of the United States, Respecting Slaves (New York: S. Wood & Sons, 1817).

Longworth’s American Almanac, New York Register, and City Directory (New York: Thomas Longworth, 1836).

Secondary sources:

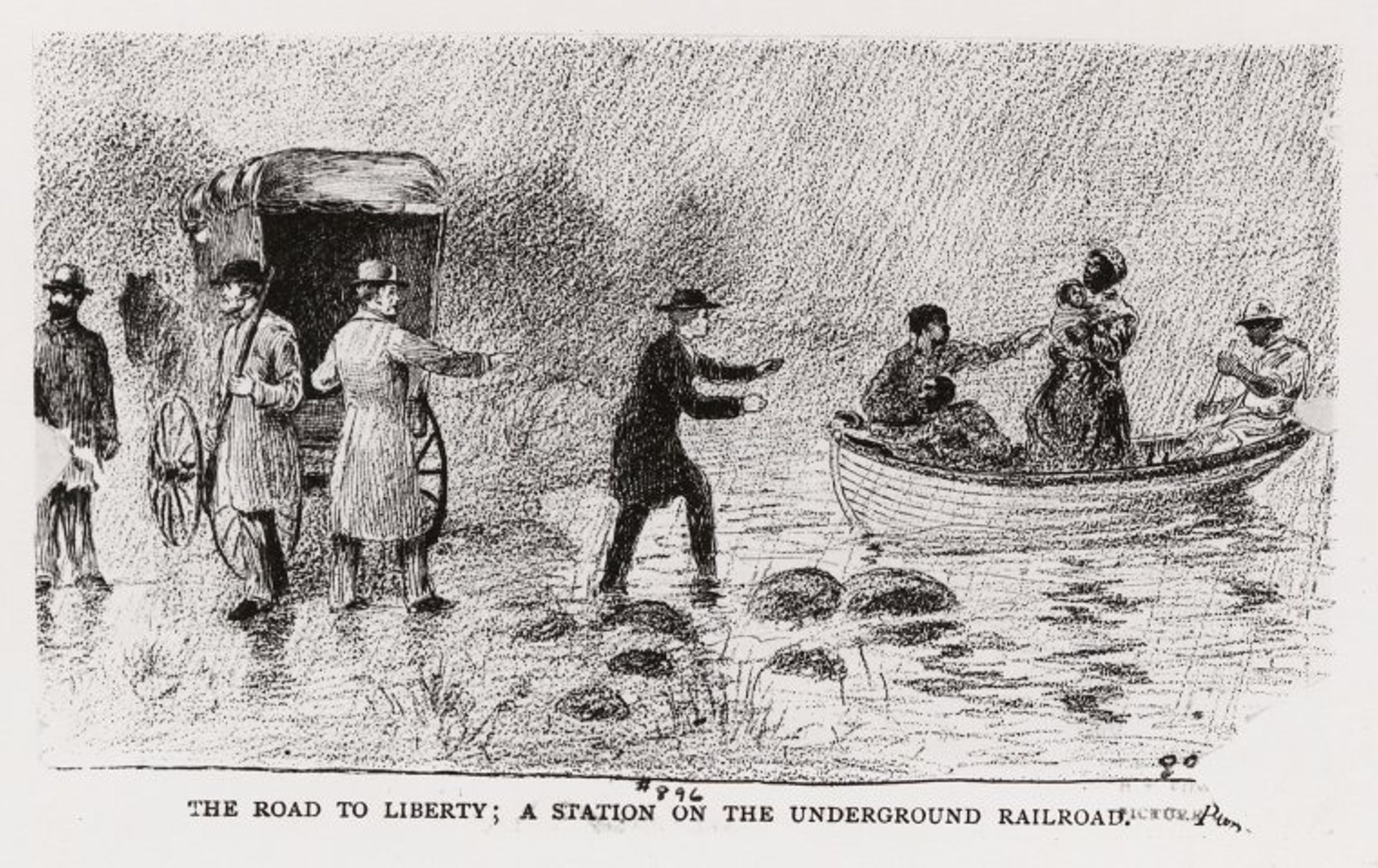

Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement (New York: Amistad, 2006).

Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of America’s Fugitive Slaves (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

Graham Russell Hodges, David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York City (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Jesse Olsavsky, The Most Absolute Abolition: Runaways, Vigilance Committees, and the Rise of Revolutionary Abolitionism, 1835-1861 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2022).

This article originally appeared in December 2024.

Isaac Kolding is a PhD candidate in English at the State University of New York at Buffalo. His research focuses on the intersection between radical abolitionist rhetoric and literature in the nineteenth-century U.S. His writing appears in American Literature, American Literary Realism, and J19: The Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists.