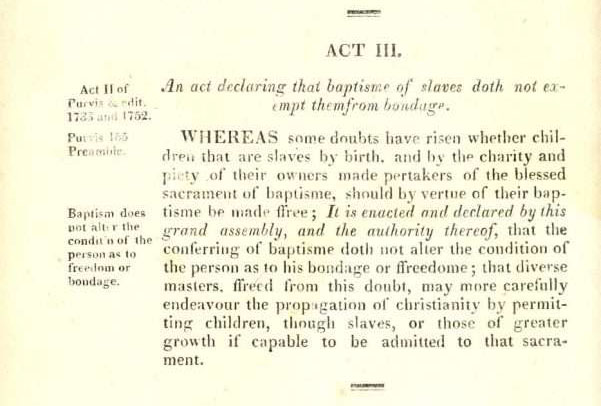

Nevertheless, in 1729, an Anglican minister named James Blair in Virginia expressed skepticism about the motives of enslaved Africans who converted to Christianity in a letter he wrote to the Bishop of London. Enslaved people were, on Blair’s account, “very desirous to become Christians; and in order to it come and give an account of the Lord’s Prayer and the Creed and the Ten Commandments, and so are baptized and frequent this church; and the Negro children are now commonly baptized.” However, he was suspicious. “I doubt not some of the Negroes are Sincere Converts; but the far greater part of them little mind the serious part, only and in hopes that they shall meet with so much the more respect, and that some time or other Christianity will help them to their freedom.”

The minister’s solution was, unsurprisingly, more theological education. “I hope their very coming to church,” he added, “will in time infuse into them some better principles than they have had.” Two years later, in the rebellion’s aftermath, Blair lamented, “it is certain that notwithstanding all the precaution we ministers took to assure them that Baptism altered nothing as to their servitude, or other temporal circumstances; yet they were willing to feed themselves with a secret fancy that it did, and that the King designed that all Christian should be made free.”

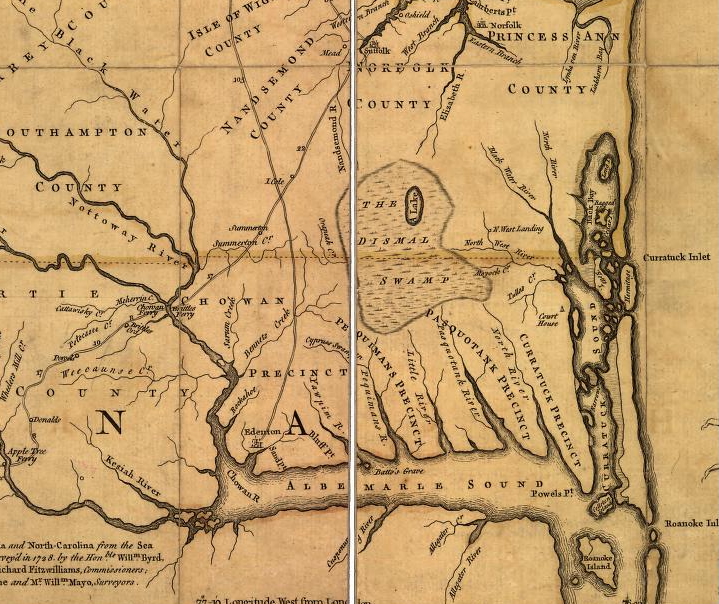

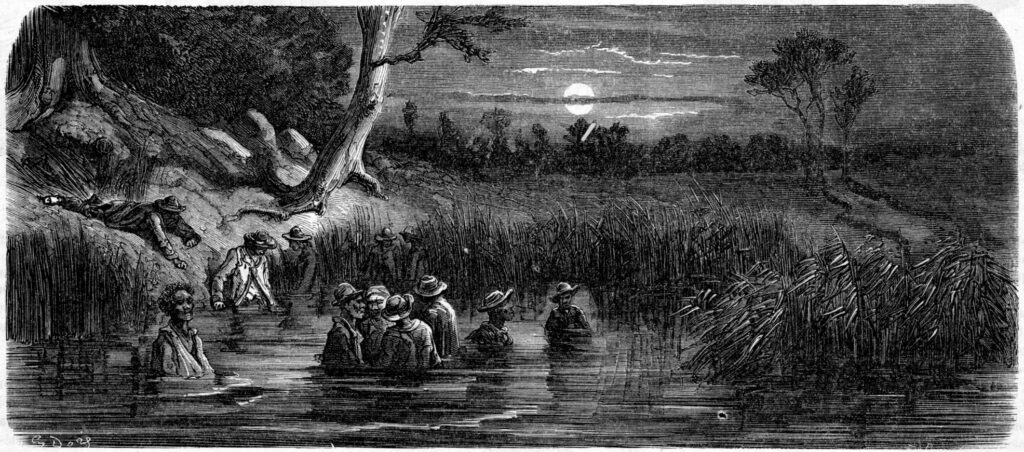

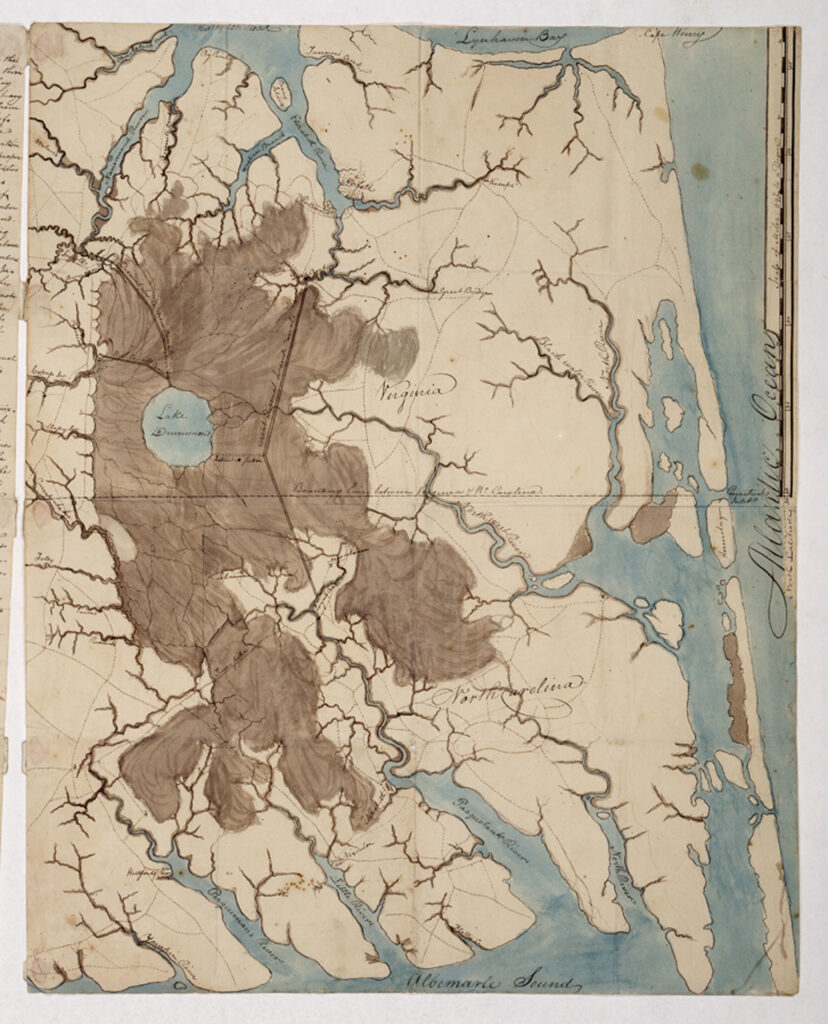

Despite his attempts to dismiss the association between Christian baptism and emancipation from slavery as foolish, the minister’s letters acknowledged that the Anglican Church was not the only source of spiritual authority, neither in the Dismal Swamp region of southeast Virginia and northeast North Carolina, nor anywhere else in the British Empire. Many of the Chesapeake rebels had their own notions about Christianity which were shaped by their broader understanding of the sources of spiritual and political power.

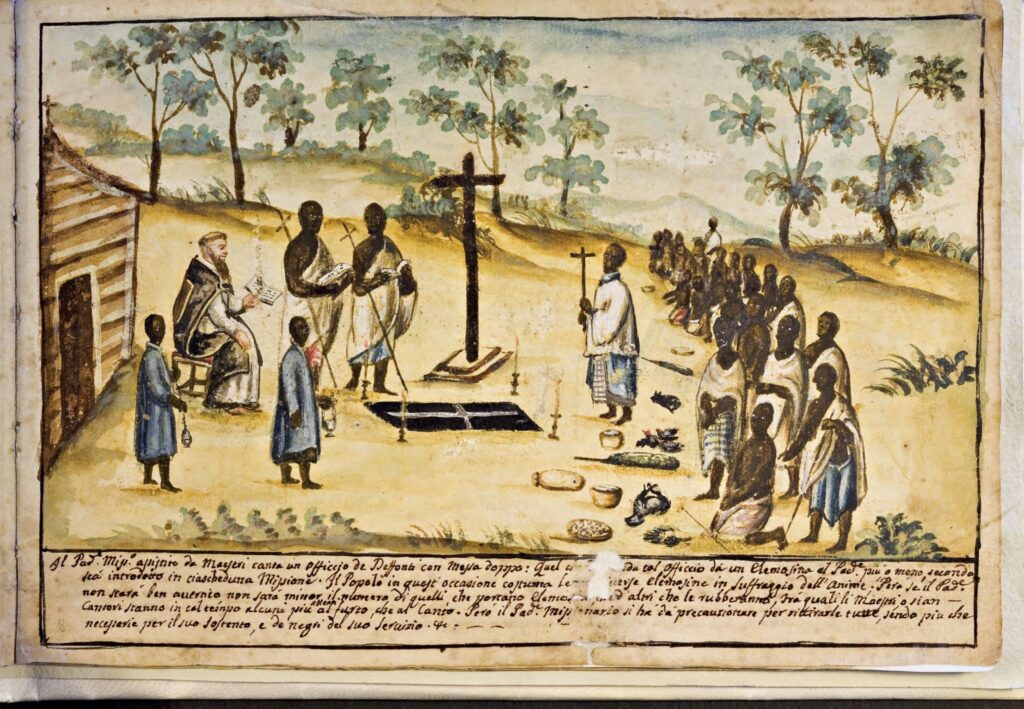

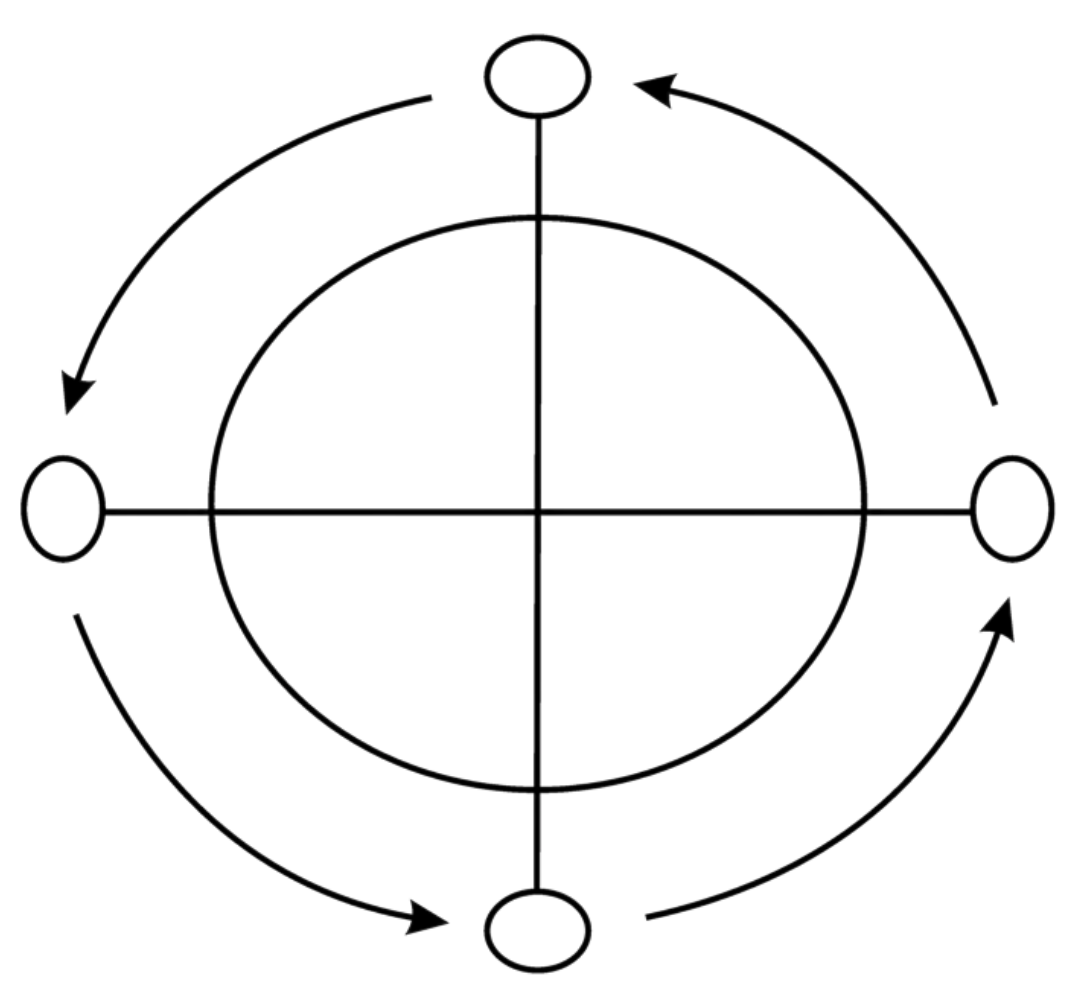

As early as the fifteenth century, Catholic Portuguese missionaries had brought Christianity into the Kongo/Angola region of West Africa, and the Kongo Kingdom had adapted Christianity as its official state religion in the early sixteenth century. After the Kongo Kingdom collapsed in 1710, in part due to civil wars fueled by the trans-Atlantic slave trade, BaKongo people made up most of the Africans enslaved by the English between 1710 and 1740. Historians have argued that among these enslaved Christians were the leaders of the Chesapeake Rebellion, and that they understood the rumors about emancipation through the lens of their Christian heritage. Sensitivity to the influence of BaKongo cosmology on Kongo Christianity provides useful context to that argument and can help us better understand the choices made by leaders of the rebellion.