Let’s stop using the term “puritan.” The migrants to English America, to whom the label has become attached, did not embrace the term, making it historically inaccurate. More importantly, our misappropriation of “puritan” has allowed scholars to ignore and the public to misunderstand religion. The price we pay in the present is a stunted and politicized understanding of the past. Instead, I propose we choose more accurate terms, accepting that “puritan” is almost never what we intend.

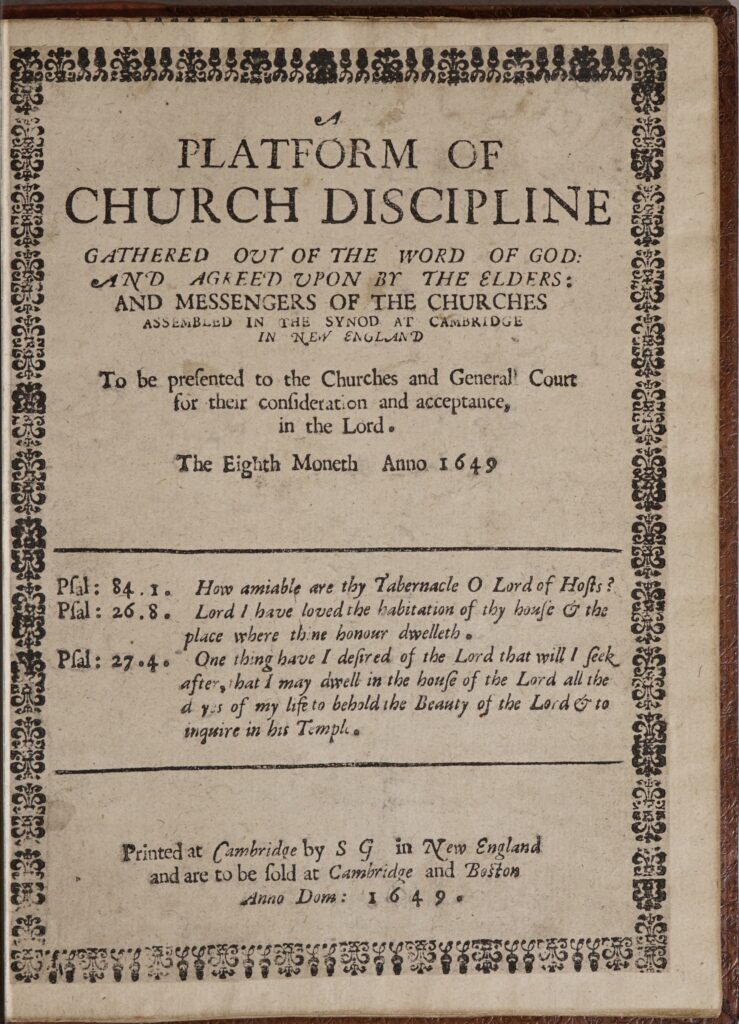

The term “puritan” emerged during the sixteenth century in debates over the nature of the Church of England. Supporters of the church’s modest reformation derided opponents who wanted a more vigorously reformed church as “puritan.” These critics sought to impose Calvinist style discipline on their communities. As a result, the label entered popular use as a taunt against those seen as rigid and judgmental. Unsurprisingly, the subjects of the term “puritan” never embraced the epithet.

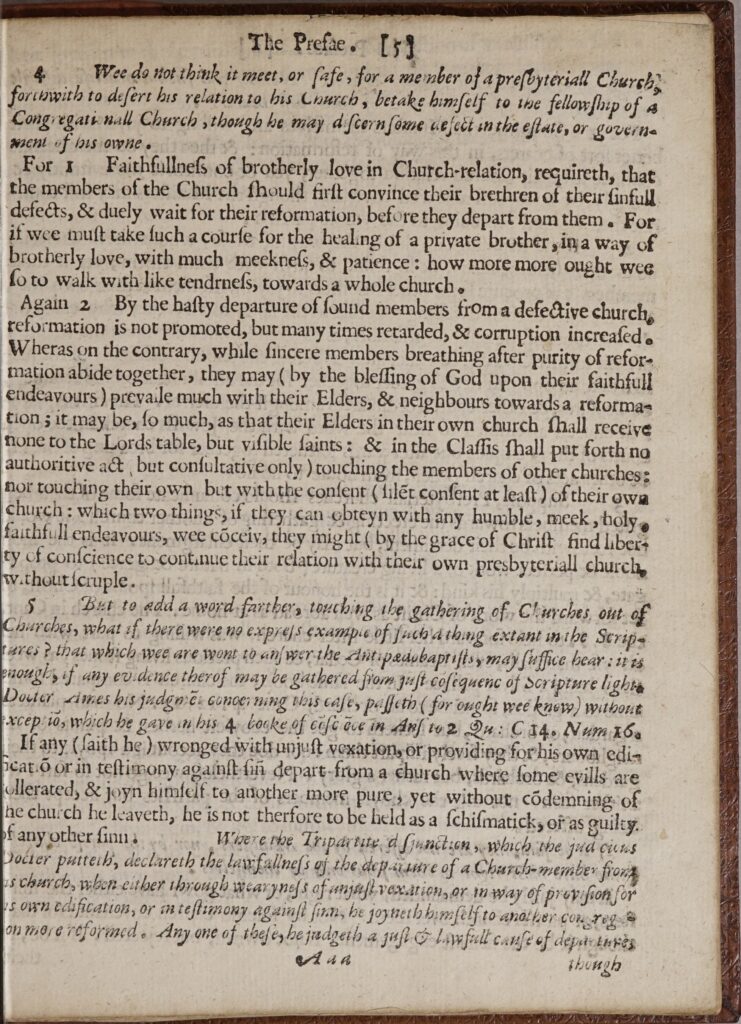

This period in English history when godly reformers worked within the established church in hopes of its reformation lasted until the 1630s, when Archbishop William Laud’s persecutions dashed these hopes. On the English side of the Atlantic, the movement for reform within the established church foundered on Laudian persecution, Atlantic migration, and (after 1640) the fragmentation associated with the civil wars and revolution.