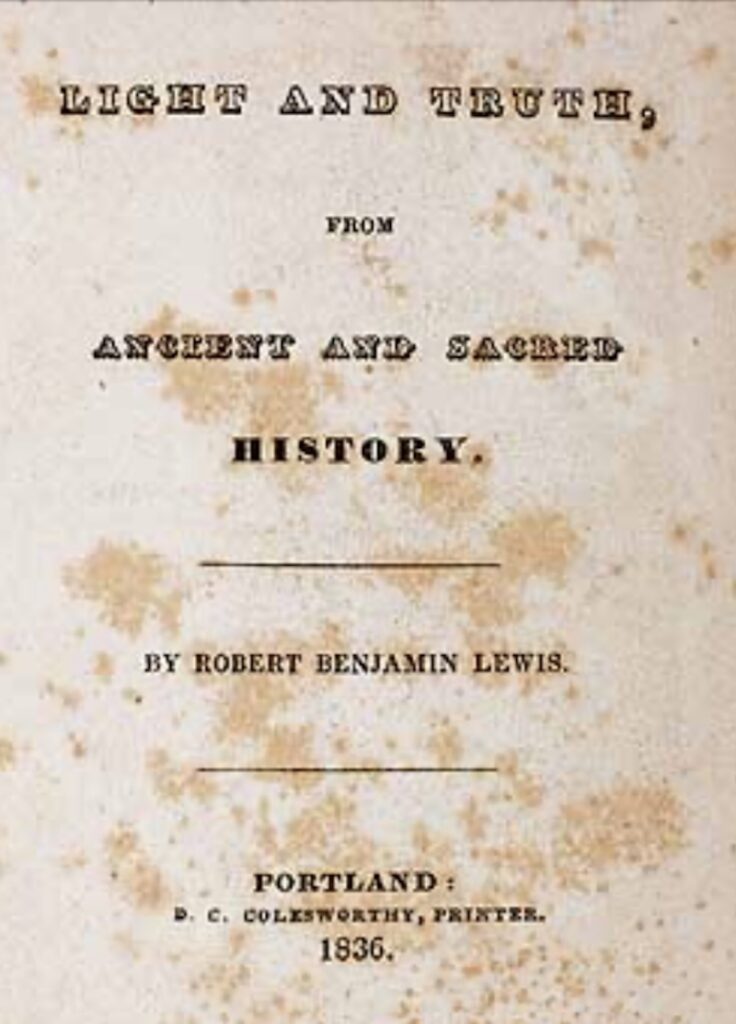

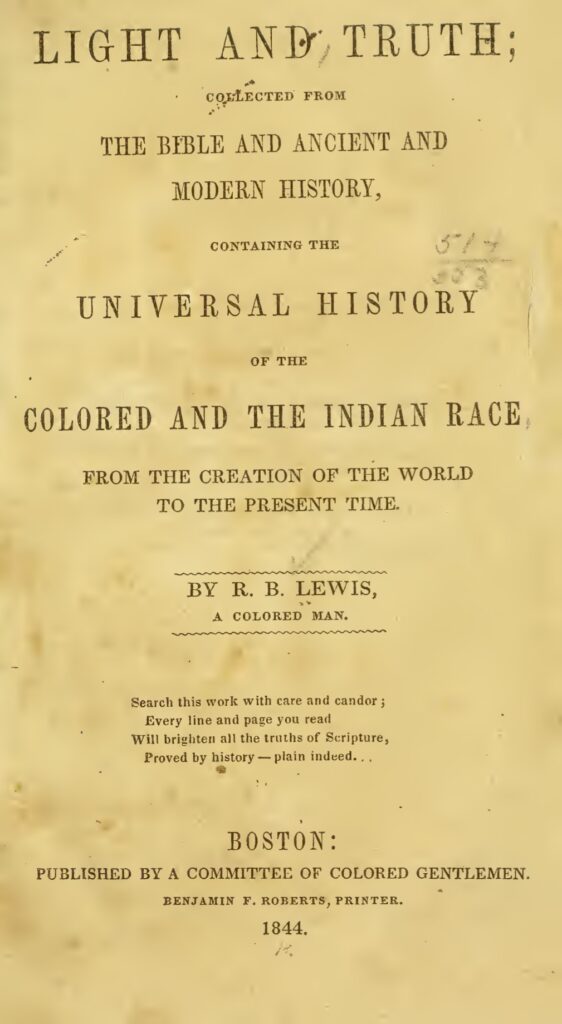

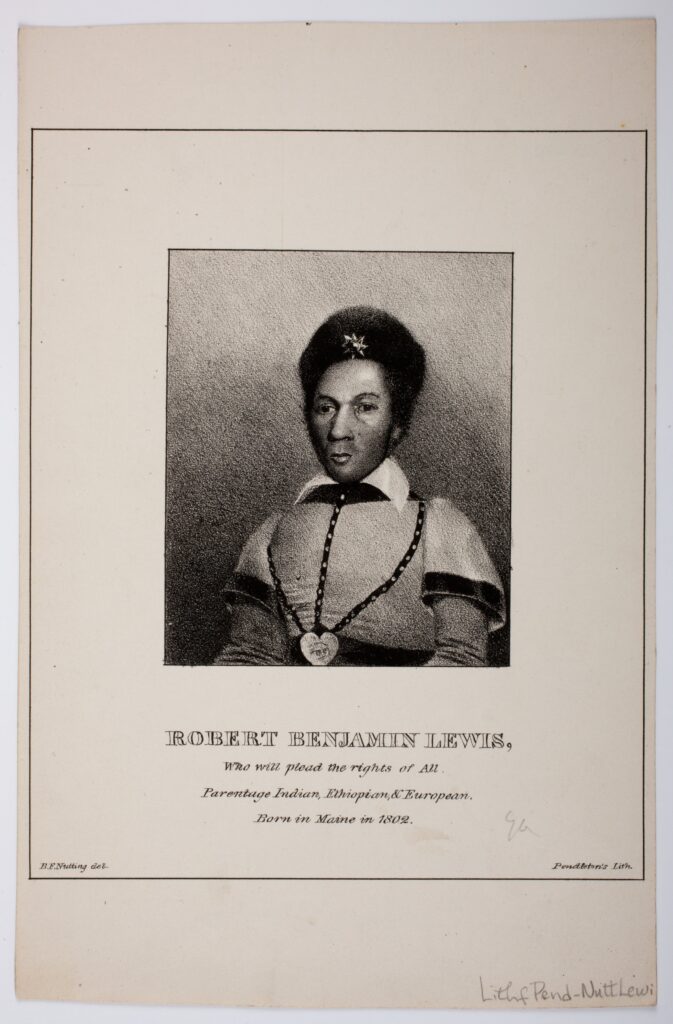

We still don’t know whether Howells actually understood who Mary Lewis and her family were, understood their educational background and community connections, or emotionally understood how the death of a Black husband and father could lead to the scattering of a previously stable and settled family and reduce a homeowning housewife to housekeeper in a stranger’s home. He casts doubt on Mary Lewis’s boasts that one of her sons (probably Euclid, b. 1846) who had gone to sea was a “prodigy of intellect”; yet given the Lewis parents’ intellectual engagement and his sister Mary Augusta’s education and later career, not to mention Esther’s quickness, one would expect the Lewis children to be bright and well-schooled. He mocks the names she had given some of her children—“it is impossible to give a full idea of the splendor and scope of the baptismal names in Mrs. Johnson’s family”—but the Lewises had named Euclid and Esther, as well as Artemisa, Hypatia, Europa, and Victorinus, after historical figures in Light and Truth, probably to give them pride in their African heritage.

Howells also states that “Mrs. Johnson could not show us her husband’s work (a sole copy in the library of an English gentleman at Port au Prince is not to be bought for money)…” His implication is that the book was likely either never written or never published; it may instead be a figment of Mrs. Johnson’s desire for affinity with the Howellses: “…we knew that she did not regard us as quality…. Yet she had a sufficient regard for the literary occupations of the family, Mr. Johnson having been an author. She even professed to have herself written a book, which was still in manuscript, and preserved somewhere among her best clothes.” Of course, the husband’s book was published in multiple editions and can still be found by anyone looking for it; maybe the wife’s manuscript, like the sampler made when she was a girl, will also be found one day.

“Mrs. Johnson” appeared in The Atlantic in January 1868. On March 29, Mary Freeman Heuston Lewis died at not quite fifty-two of “inflammatory fever” at 80 Phillips Street, back in the heart of Black Boston. Did the Howellses know? Esther died in Charlestown, aged not quite sixteen, in 1871, the same year Suburban Sketches was published. Had the Howellses kept in touch with her?

We don’t know how many people reading “Mrs. Johnson” when it appeared in The Atlantic or Suburban Sketches recognized the Lewises and William Johnson. Howells didn’t make much effort to disguise them. As offensive as the essay is—and, we can assume, was to some of its contemporary readers—Howells has inadvertently given us, more than 150 years later, valuable information about an important but nearly forgotten family and its networks.

Further Reading:

For suggestions of where more hidden information concerning the Lewis family might be found, click here.

Bay, Mia. The White Image in the Black Mind: African-American Ideas about White People, 1830-1925. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Ernest, John. Liberation Historiography: African American Writers and the Challenge of History, 1794-1861. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Goldman, Susan, and Carl Dawson. William Dean Howells: A Writer’s Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Merrill, Ginette de B., and George Arms, eds. If Not Literature: Letters of Elinor Mead Howells. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1988.

Nell, William C. William Cooper Nell: Selected Writings 1832-1874, ed. Dorothy Porter Wesley and Constance Porter Uzelac. Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2002.

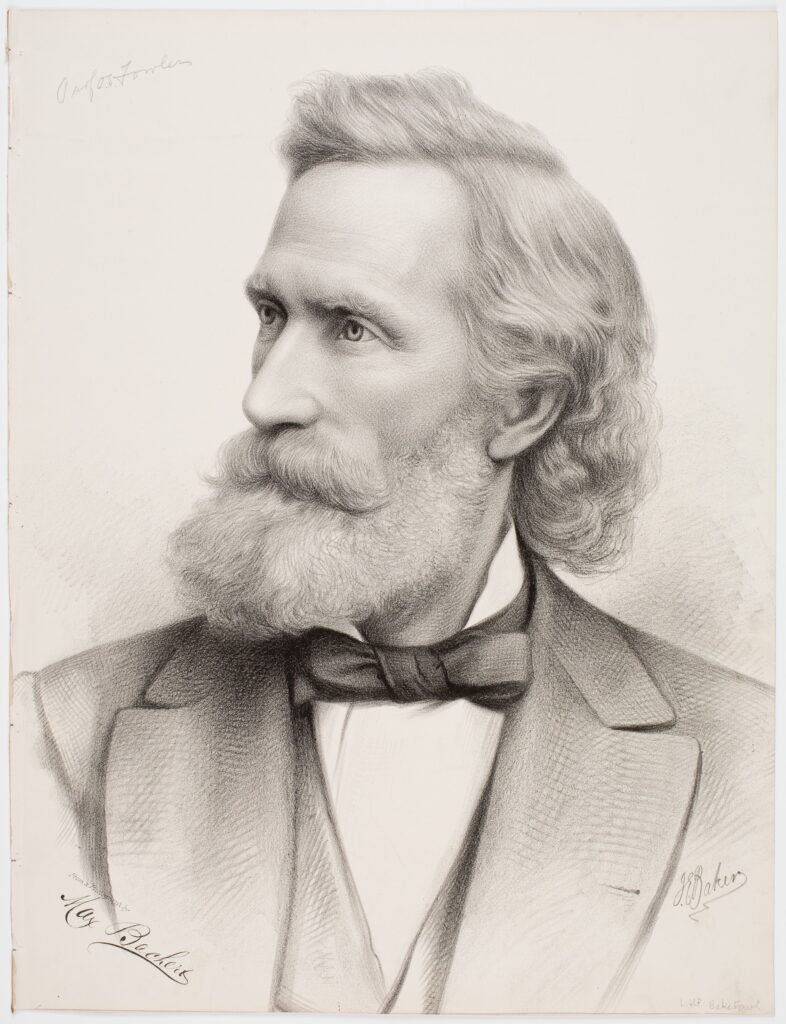

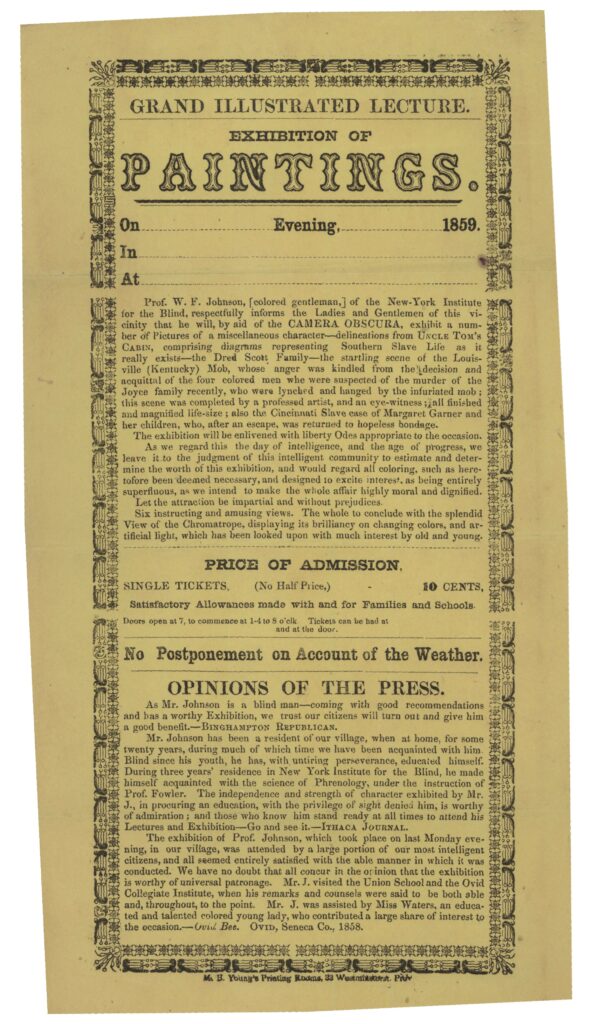

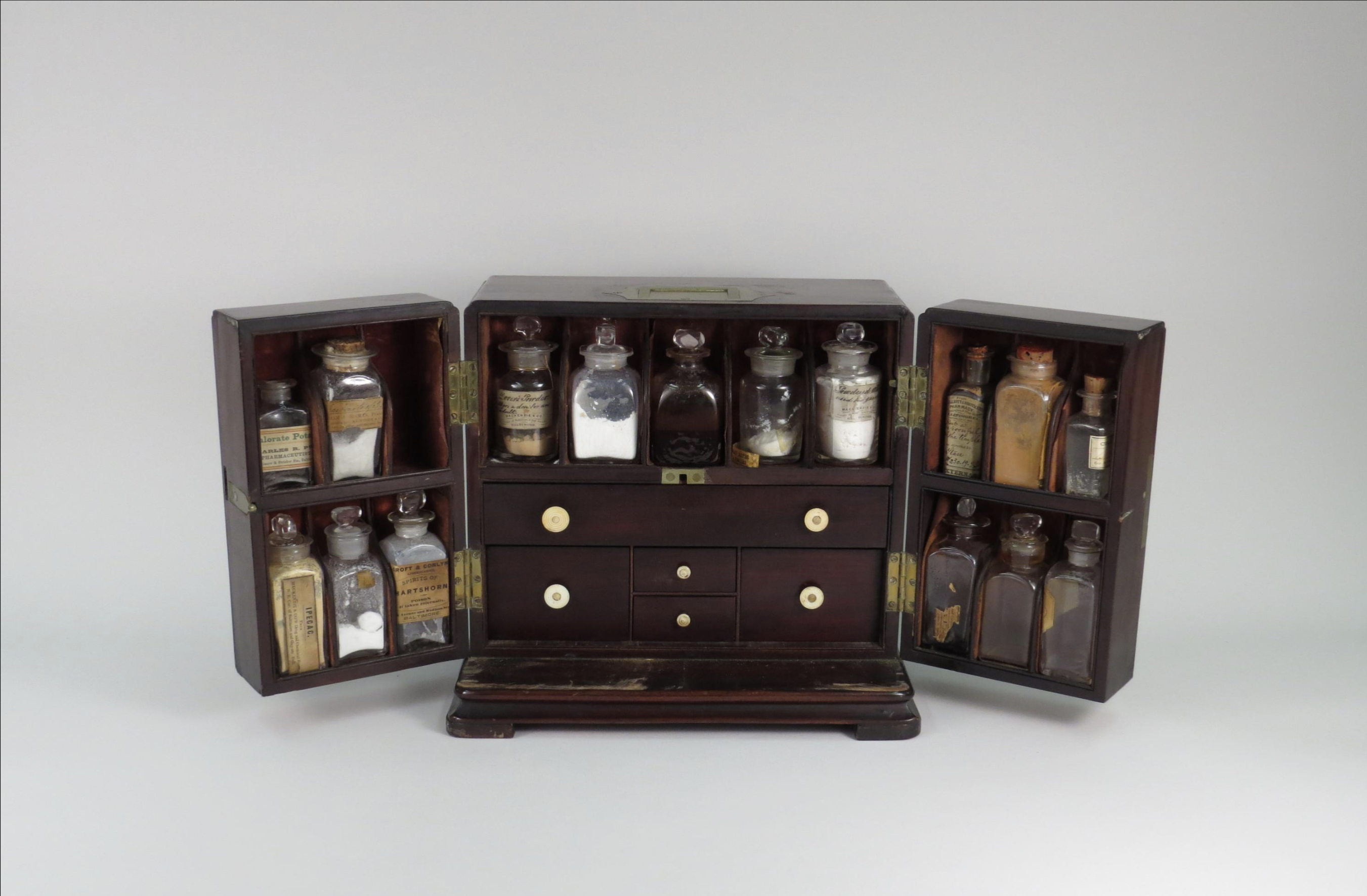

Piola, Erika. “Rev. W. F. Johnson: Blind Phrenologist, Abolitionist, and Picture Show Lecturer.” Beyond the Reading Room (blog), Library Company of Philadelphia, September 30, 2015, http://librarycompany.blogspot.com/2015/09/rev-wf-johnson-blind-phrenologist.html.

Pitts, Reginald H. “Robert Benjamin Lewis.” In Maine’s Visible Black History, edited by H.H. Price and Gerald E. Talbot, 235-40. Gardiner, Maine: Tilbury House, 2006.

Rusert, Britt. Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture. New York: New York University Press, 2017.

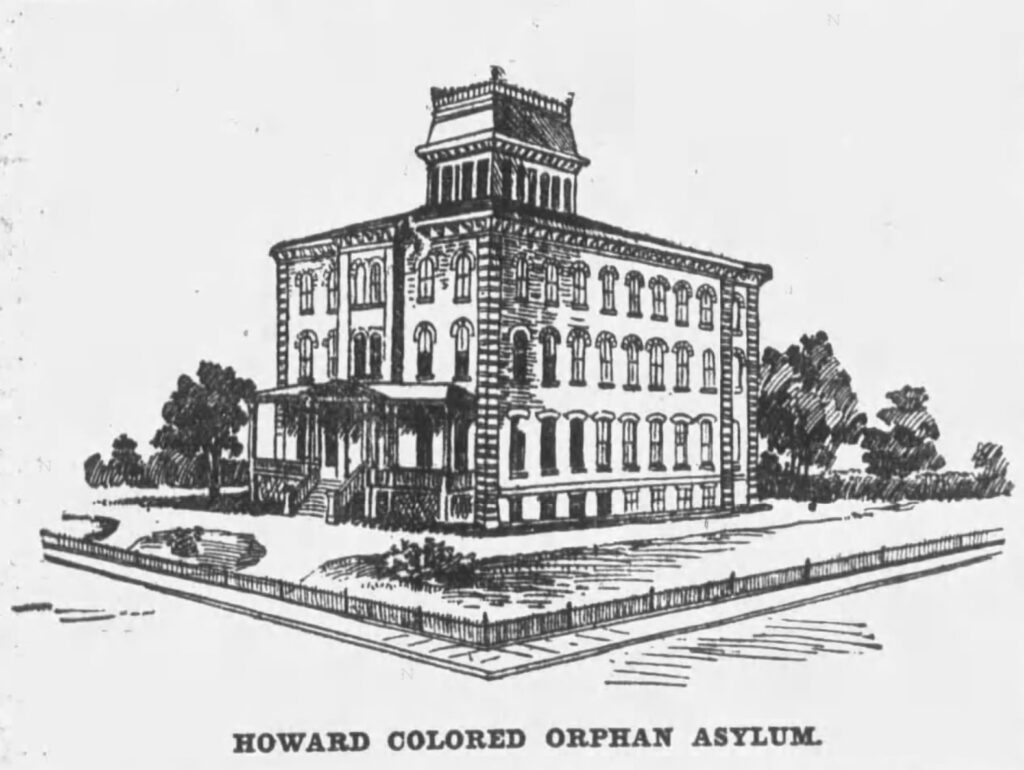

Wellman, Judith. Brooklyn’s Promised Land: The Free Black Community of Weeksville, New York. New York: New York University Press, 2014.

Wells, Kentwood D. “The Magic Lantern in American Churches before 1860.” The Magic Lantern Gazette 27, no. 4 (Winter 2015): 3-33, https://www.academia.edu/40298208/Kentwood_D_Wells_2015_The_magic_lantern_in_American_churches_before_1860_The_Magic_Lantern_Gazette_27_4_3_33.

This article originally appeared in May 2025.

Leslie Brunetta is a member of the Cambridge Black History Project and has published a number of articles on forgotten Black history in that Massachusetts city. She is also co-author, with Catherine L. Craig, of Spider Silk: Evolution and 400 Million Years of Sitting, Waiting, Snagging, and Mating (Yale University Press).