While Donald Trump grabbed the nation’s, and the world’s, attention in the battle for the Republican presidential nomination, one of the more unusual contenders on the Democratic side passed by rather unnoticed. “Meet Lawrence Lessig, The Candidate With A Single Issue,” read the headline of an October 2015 National Public Radio profile of the Harvard Law Professor who had just reached his goal of crowdfunding one million dollars in small donations within thirty days. Lessig never seriously figured in the principal contest between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, but he did briefly outpoll experienced rivals Lincoln Chafee, Martin O’Malley, and Jim Webb before his withdrawal from the race after four months, which he blamed on the Democratic National Committee’s rewriting of the rules to exclude him from their televised debates. In his final message to the American people, Lessig once again pressed the importance of the single issue that headlined his NPR profile: campaign finance reform. His own campaign Website declares that “the system is rigged to favor the powerful and well-connected, and it ignores the voices of ordinary citizens. Our representative democracy has become so corrupted by this fundamental inequality, that only those who fund campaigns are represented. The result is the governmental dysfunction that we see today.” Elsewhere, in a piece penned for The Atlantic, Lessig argues that “Washington will not change until the economy of influence fueled by the lobbying-industrial-congressional complex is radically changed.”

Those who doubt the existence of a “lobbying-industrial-congressional complex” should consult the Website of the Center for Responsive Politics—a non-partisan research group that “tracks money in U.S. politics and its effect on public policy and elections”—which calculates that $3.2 billion dollars was spent lobbying the federal government in 2015, with over 11,000 lobbyists registered as active in the national capital (fig. 1). So why does it take a political outsider to place this important issue at the center of the 2016 election? Lessig suggests that this very fact is symptomatic of the fundamental corruption of the American political system in its current form; because his opponents are so dependent upon contributions from lobbyists to fund their own campaigns, they dare not speak out against them. The center identifies 337 lobbyists who have donated directly to one or more candidates’ campaign committees; this figure includes a number of “bundlers” who collate donations from multiple clients. Daniel Auble, a senior researcher for the center, told Capitol Hill newspaper Roll Call that lobbyists are unusual among donors in giving to both parties, and this fact “lends some credence to the idea that some of these contributions are more transactions or practical than ideological.” One lobbyist was even quoted in the same article as admitting that “elected officials spend too much time raising money, and their time would be better spent focusing on policy.” No wonder 69 percent of respondents to one recent poll conducted by NBC and the Wall Street Journal across all demographics and partisan affiliations agreed with the statement that “I feel angry because our political system seems only to be working for the insiders with money and power, like those on Wall Street or in Washington, rather than working to help everyday people get ahead.”

We should not be surprised by these revelations, however, for lobbying is hardly a novel feature of American politics. Political scientists have tended to treat it as a twentieth- and twenty-first-century phenomenon. A few historians take the story back further, dating its emergence to the massive expansion in the powers of the federal government during the Civil War era. In truth though, lobbyists have been active in Washington, D.C., almost from its founding. Indeed, 2016 will mark not just the election of the forty-fifth president of the United States, but also the 200th anniversary of the creation of the first ever lobbying agency in the national capital, an agency that was founded by a Delaware factory manager named Isaac Briggs.

Isaac Briggs was a man of many talents. Born in Haverford, Pennsylvania, in 1763, he studied at the College (now University) of Pennsylvania, at a time when very few Americans received a college education. After graduation, he served as secretary to the convention which ratified Georgia’s state constitution, helped survey the boundaries of the District of Columbia, taught school, trained as a printer, and tinkered with a design for an early steamboat engine. He was elected to the prestigious American Philosophical Society in 1796, formed a friendship with fellow member Thomas Jefferson, and was appointed by the latter as surveyor general of the Mississippi Territory following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. It was after that appointment expired that Briggs moved into textile manufacturing, as part of a consortium of investors who established the mill town of Triadelphia, Maryland, in 1809 (the town no longer exists, having been wiped out by flooding eighty years later). Financial problems with his Maryland venture in 1814 prompted his move to Delaware, where he took on management of the Wilmington factory of Thomas Little & Company.

The business that took Briggs from Wilmington to Washington in 1816, and secured his own small place in American history, was the Dallas Tariff Act. The United States’ infant manufacturing sector had flourished over the previous two decades, cut off from foreign competitors by the Revolutionary Wars in Europe, but the return of peace reopened domestic markets to cheap imported wares. The beleaguered proprietors clamored for the federal government to raise tariff barriers against this flow of goods from abroad; “already the great importations glut the market, lower the price, and extend the credit, and I am certain in two years will lay in ruin, eighty percent of the present existing manufacturers,” pleaded one typical letter to the Treasury Department. The Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander James Dallas, responded by proposing to Congress a new schedule of rates which would serve to protect home industry. Whether Congress would follow the secretary’s lead was still in doubt, however, when Briggs set out for the national capital in December 1815, at the behest of his neighbors that he “communicate with members [of the government] on the just & reasonable objects of the manufacturers of this District.” The trip was funded by “levy[ing] a Tax on each and every Manufacturer (and those immediately concerned therewith) within a circuit of twenty miles of Wilmington,” with subscriptions ranging from five to twenty-five dollars, even the former of which would have been far beyond the purse of an ordinary factory worker. Even at this early period, money talked in American politics.

Upon arriving in Washington, Briggs soon discovered he was not alone in his mission. From Rhode Island came James Burrill Jr., a lawyer of some repute, recently appointed chief justice of his state’s supreme court, and taking time out between sessions to argue the case of local mill owners at the capital. New York sent Matthew Livingston Davis, a journalist and printer, best known to history for refusing to testify against his friend Aaron Burr following the latter’s fatal duel with Alexander Hamilton, an act of defiance for which Davis had spent time in prison. And New Jersey was represented by Charles Kinsey, himself a papermaker and well-versed in the arguments for protective legislation. “They are all men of talents,” was Briggs’ verdict after their first meeting, “and in the selection of them the manufacturers have given a proof of wisdom.”

Yet the presence of his fellow delegates also gave Briggs cause for concern: would their small lobby be able to act in concert? To this end, on January 13, 1816, he called together his new associates in a committee room in the capitol building, furnished for the purpose by a sympathetic congressman. “I made to them a little speech; on the importance of our speaking the same language, as we had in view the same object—if we should be found some pressing one point, and some another, incompatible, one using this mode of reasoning, and another that, irreconcilable with each other, we should not succeed,” Briggs recorded. He then proposed “that we form ourselves into a Society, under a proper organization, have regular and stated meetings, and each one should communicate his ideas to the Society previously to publication elsewhere.” “This motion was unanimously approved,” he noted happily, “and accordingly James Burrill was appointed President and Matthew L. Davis Secretary.” Thus was founded Washington’s first ever lobbying agency.

Burrill, Davis and Co. were certainly kept busy. Attending congressional debates, conversing with lawmakers, and writing in favor of protection, all these were “engagements laborious and incessant,” Briggs complained to his wife, adding “I have seldom gone to bed before midnight.” Several times they were invited to address the House of Representatives Committee on Commerce and Manufactures, and these occasions were attended by “a very crowded audience, mostly of members of Congress,” who listened “with great attention and respect” to their arguments. “I have often the pleasure to see our friend and your delegate Briggs,” one senator informed a correspondent in Delaware, “—he is very zealous and active in mixing with the Members and I have no doubt is an excellent choice—I think so far as I can collect that the Manufacturing Interest stands well in the minds of a considerable majority of Congress.” Sure enough, while the national legislature was not quite so generous in setting the new rates as the Secretary of the Treasury had recommended, they adopted the principal features of his proposal in the tariff act which came to bear his name. Their assignment completed, Briggs and his allies went their separate ways. Still, while their association was only a temporary one, their activities heralded the increasingly important role that lobbyists would come to play in national policymaking over the following half-century.

Three years later, the tariff was back on the congressional agenda, and the manufacturers launched a new lobbying campaign with their first national convention. The prompt for this meeting was the Panic of 1819, a financial crisis that devastated the American economy. “This distress pervades every part of the Union, every class of society,” lamented one commentator. “It is like the atmosphere which surrounds us—all must inhale it, and none can escape it.” On November 29, 1819, one week before the opening of a new session of Congress, thirty-seven delegates from nine states gathered in New York City for a “Convention of the Friends of National Industry,” to decide how best to pursue their common goal of securing federal aid for domestic producers. At a time when horseback was still the fastest way to travel, this was no small achievement; indeed, it would be another decade before any political party managed to hold its own national convention. Briggs did not attend, having left the textile business to work as a canal engineer, but his former colleague Matthew L. Davis did participate in proceedings. Those present adopted a resolution recommending to their fellow citizens the formation of “societies for the encouragement of domestic industry,” and a petition to Congress pleading for a further increase in tariff rates.

The task of drawing up suitable legislation on the subject fell to Henry Baldwin, representative for the industrial town of Pittsburgh—the “Birmingham of America”—and chair of the House Committee on Manufactures. Baldwin quickly found the tariff to be “a work of labor to write,” complaining that “it is impossible for one mind to view a subject in all its possible scope.” This should hardly be a surprise, for politics was still a part-time occupation for most lawmakers during this period; few could be considered experts on political economy, and with a turnover rate of approximately one-third from one Congress to the next, a significant proportion lacked any national legislative experience whatsoever. In desperation, Baldwin sent early drafts of his work to contacts among the manufacturing community, urging them to “suggest any amendments or alterations which strike you or your friends.” Sensing an opportunity, the manufacturers responded by sending their own man, Eleazar Lord, an agent of the New York-based American Society for the Encouragement of Domestic Manufactures, to assist Baldwin in Washington.

Lord, like Briggs before him, had many strings to his bow, a common characteristic of these early amateur lobbyists before lobbying itself became a recognized profession. Born in 1788 in Franklin, Connecticut, Lord originally planned to devote his life to the church, obtaining his license as a Presbyterian preacher in 1812. But a recurrent eye problem forced him to give up his spiritual calling and re-enter the secular world, where he engaged in banking and later established the Manhattan Fire Insurance Company. He remained active in religious ventures though, most notably as a founding member of the American Bible Society, and retained a rather pious attitude to the informal politicking which pervaded Washington’s social scene. Whereas Briggs had enjoyed socializing with the nation’s political elite, sharing a boarding-house with several congressmen and even dining with President Madison and his family, Lord stiffly informed his employers several weeks into his stay: “I can give but a poor account of the levees, for I have not been to one, nor to any balls, events, or other places of idleness, dissipation, folly, iniquity, & nonsense. Were I disposed to attend such assemblages any where it should not be here. With the views & feelings I have of the solemn responsibility of the representatives, especially at a period like this, & of the manner in which 4 months of their time was whiled away I should feel humbled & ashamed to meet one of them at such a place.”

Lord’s appearance was clearly a blessing for Baldwin. “I did not arrive here a moment too soon,” the New Yorker reported in early January 1820. “I am set at work drafting a schedule of a new tariff. Material alternations & additions can be made if adequate information & statements can be furnished.” “Mr. Lord is here and is very useful,” his new collaborator reiterated three weeks later. By the end of February, the two men were laboring on Sundays and dining together in the committee room as they struggled to complete their mammoth task. At the same time, Lord also cooperated with other members of the Committee on Manufactures to identify wavering legislators and hand deliver them protectionist literature, as well as depositing spare copies in the Library of Congress, to the gratification of future historians. For four months he persevered tirelessly in the cause, filing near-daily reports of proceedings both on and off the floor, in spite of the numerous discouragements that he faced. As he complained on one occasion, “an advocate of Manufacturing here seems to me to be regarded as a kind of insidious, designing & dangerous enemy who against all reason & prosperity wants to filch some favour from the guardians of the country.”

Unfortunately for the manufacturers, Baldwin’s Bill, as it was known to contemporaries (though it might more justly have been labeled Lord’s Bill), was defeated by a single vote in the Senate in May 1820. Nonetheless, Lord earned much praise for his work on their behalf. He was rewarded with editorship of a protectionist newspaper in New York, and the presentation of a silver pitcher from the “friends of National Industry,” in approbation of “the Zeal, talents, and intelligence he displayed at Washington, in support of American Manufacturers, during the first session of the sixteenth Congress.” Lord may not have succeeded in his mission, but the extensive cooperation between he and Baldwin in drawing up the new tariff and pushing for its passage presaged the kind of cozy relationship between legislators and lobbyists that has become commonplace today, to the alarm of critics like Lawrence Lessig.

The first presidential election in which lobbying played a significant role was probably that of 1828. Once again, the story begins with a national convention of manufacturers, this one held in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in July 1827. Ninety-eight delegates attended, representing thirteen of the twenty-four states in the Union. These included two sitting senators and four representatives, one of them the current chair of the Committee on Manufactures, along with a further nineteen who had previously served in the Congress; this figure illustrates that the so-called “revolving door” between governing and lobbying is by no means a new phenomenon. The Harrisburg Convention also embraced a more ambitious agenda than its New York predecessor, committing to paper a whole schedule of rates which it recommended for the attention of the national legislature. “Now there is not a petty manufacturer in the union from the owner of a spinning factory, to the maker of a hobnail—from the mountains of Vermont to the swamps of the Patapsco, who is not pressing forward to the plunder,” complained one commentator. These advocates of high tariff barriers, he added, were “a combining, club-meeting, planning, schemeing, petitioning, memorializing, complaining, statement-making, worrying, teasing, boring [a contemporary term for lobbying], persevereing class of men.”

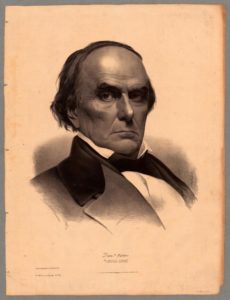

The Harrisburg Convention immediately became a focal point of conflict between supporters of President John Quincy Adams and their opponents who favored the election of Andrew Jackson (fig. 2). “The real design of this convention at Harrisburg is not to advance American industry, but to organize a political club under the direction of the Administration of the general government to direct and control public sentiment,” accused an Opposition newspaper. “Doubtless there are manufacturers among its members, who think they have an interest in its proceedings; but the greater part of them are unquestionably actuated only by a desire to seduce [voters] from the cause of Jackson, under false pretences that himself and friends are opposed to a tariff, while Mr. Adams is in its favor.” The convention’s organizers, in turn, denied any partisan motivation. “The friends of Domestic Manufactures would have been madmen to break down their strength by mingling the economical plans with political matters,” wrote one, for they “are anxious that there may be unanimity upon the subject, and certainly will not mix up anything with the main object that might tend to invite opposition.”

The doings of the Harrisburg Convention dominated the agenda of the final session of Congress before the 1828 election. “The [protective] ‘System’ and the ‘opposition’ to it forms the two elementary principles of the two parties,” one observer recorded. “It was the Basis of the Harrisburg Convention: It is the leading Subject of debate in Congress: It is alluded to in every debate upon every other Subject. It is the leading Subject of State resolutions—some for & some against the System. It is a Standing question in the Newspapers and the principle topic of Conversation in all circles of Society public & private throughout the union.” Meetings were held across the country, urging legislators to adopt the proposals put forward by the convention, and several of the Harrisburg delegates were called upon to testify before the House Committee on Manufactures. Sympathetic congressmen lined up to praise those who attended; “they were not speculators, nor wild theorists, but practical men,” declared one, “—the farmer, the manufacturer, the merchant, the wool-grower and manufacturer, there met,” and he favored an increase in rates, “not only from his own investigation of the subject, but from the[ir] recommendation.” In response, critics questioned their impartiality. “No combination of wool growers and woollen manufacturers, should ever attempt to dictate a tariff to the people of the United States,” proclaimed future president James Buchanan. “They would be more than men, if self-interest did not prejudice their judgment, and call forth propositions for their own benefit, at the expense of the community.”

The result of all this too-ing and fro-ing was the so-called Tariff of Abominations, which imposed some of the highest, and most unevenly distributed, rates in American history. Jackson supporters in Congress assiduously courted states that might prove pivotal in the forthcoming election, offering protection to Kentucky hemp planters, Pennsylvania ironmasters, New York wool growers, and Midwestern grain farmers, while punishing New England industries for their loyalty to Adams. But the real loser was the South, which possessed little manufacturing of its own to benefit from the changes, but would now have to pay higher prices for its imported goods. Historians have recognized Southern anger over federal tariff policy as a source of growing sectional tension during this period, culminating in the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833, but they have overlooked the particular role that lobbying played in that process. For Vice President John C. Calhoun, who would devise South Carolina’s doctrine of nullification, the Harrisburg Convention was “the selected instrument to combine with greater facility the great geographical Northern manufacturing interest in order to enforce more effectually the system of monopoly and extortion against the consuming States.” Thomas Cooper, in his famous “calculate the value of the Union” speech, concurred in this analysis. “There is a mongrel kind of lobby legislation attending at Washington,” he charged, “that operates from without on the members within: giving such statements (uncontradicted) to the various committees, as may best secure the interest of the manufacturers, and directing and managing the votes, as the occasions may require” (fig. 3).

Lobbying has always been controversial, but its practitioners have successfully argued that it is protected by the Constitution. “As a republican citizen, I claim the right of addressing, with respect and decorum, orally & in writing, any man either in or out of congress,” declared Isaac Briggs in 1816, and the existence of that right has been confirmed by several Supreme Court rulings over the the past century. Of course it is not the right of every American citizen to lobby his or her elected representative that concerns critics like Lawrence Lessig, it is the special influence that some professional lobbyists, acting on behalf of wealthy corporations, have exercised in return for funding the campaigns of sympathetic politicians. But where should we draw the line between proper and improper relationships, and how can we prove when wrongdoing has taken place? This too was a problem for nineteenth-century Americans.

Henry Clay built a forty-year career in national politics upon his championing of high tariff barriers (fig. 4). Along the way, he received countless gifts from grateful constituents, including: parcels of cloth; glass and silverware; a spade, shovel, axe, hoe, carving knife and fork; “two pair of Indian rubber over shoes,” a dozen kid gloves, countless hats, and, for the rare occasion he found himself without a hat, four combs; “a bureau travelling trunk,” presumably to keep it all in; “half a dozen bottles of American Cologne water;” several rolls of wallpaper; a pocket knife; a plough; a dozen scythes; and twenty-three barrels of salt. Today, congressional rules prohibit members accepting gifts of any kind from a registered lobbyist, and gifts of more than fifty dollars value from any other source. Prior to the Civil War, in contrast, there was no register of lobbyists, and no rule on accepting gifts. Still, no one seriously accused Clay of seeking to profit from these transactions, though one newspaper writer did jokingly suggest that he might “get up an auction” to dispose of all the “curious articles” sent him by his supporters. They were intended, a donor explained, “as a testimonial of our respect and esteem for the great advocate of protection of domestic manufacturers,” and were neither solicited by the recipient nor of sufficient worth to have influenced his stance on the tariff.

Much more questionable is the conduct of another great American statesman of the period, Daniel Webster (fig. 5). Webster enjoyed a close relationship with many wealthy capitalists, and was remarkably candid about what he described as “subscriptions,” “gifts” and “sweeteners” that he received in order to enable him to make the “financial sacrifice” his continued service in Congress required. Having previously led the fight against increased rates, Webster was a notable convert to protectionism in 1827, the year of the Harrisburg Convention, and just around the same time that a group of Boston manufacturers generously offered him a substantial share in their textile factory. “I can easily believe that a rumoured investment of $50,000 in the Lowell manufacture, may have conquered the heterodoxy of Mr. Webster’s former opinions, and brought him over to the true faith,” commented Thomas Cooper sarcastically, on hearing news of the deal. The terms were such that Webster would not actually pay cash for the shares, but would still enjoy the dividends on credit; in fact, he never paid for them at all until he came to sell them, at a substantial profit, nearly a decade later. “All Webster’s political systems are interwoven with the exploration of a gold-mine for himself,” was the verdict of John Quincy Adams on his Massachusetts colleague’s association with his financial benefactors.

Adams himself provides an example of a lawmaker who took his civic responsibilities extremely seriously. “My principle has always been to refuse all presents offered to me as a public man,” he once recorded rather primly in his diary. Yet even this seemingly straightforward policy was tested when he received a parcel containing several small soaps from an admirer. He initially resolved to insist on paying for the present, but his wife “shamed me out of that fancy,” and he reluctantly decided to accept them. “Where the value is very small, I thought it would be ridiculous to make a point upon it,” he rationalized, before adding, tellingly, “it has not always been easy for me to draw the line of distinction.”

One incidence in which contemporaries did agree that wrongdoing had been committed became public knowledge after a congressional investigation into corruption surrounding the passage of the Tariff of 1857, one of a spate of such investigations into lobbying during that decade. The inquiry was prompted by the bankruptcy of a Massachusetts textile manufacturing company, Lawrence, Stone & Co., whose financial records subsequently disclosed the expenditure of some $87,000 in connection with a mysterious “tariff account.” One partner in the company attempted suicide, another fled to Europe, leaving the third, William W. Stone, to face the music in Washington. Stone’s testimony implicated a number of politicians, both in and out of Congress, and revealed startling details about the methods by which interested parties were already seeking to influence national legislation.

A cabal of woolen textile manufacturers, it transpired, had been for several years secretly cultivating public opinion in favor of admitting raw wool duty free, to increase the profit margin on their own product. Stone admitted that he had met frequently with newspaper editors to promote their cause. “I never offered to pay them one farthing, and they never asked any such thing,” he maintained, but did admit that wherever a favorable article appeared, his associates would buy up large numbers of copies for distribution, and the author might receive “a bonus” for his trouble. The investigating committee also found that the mill owners had “sought to propitiate and conciliate leading and influential men, in all the political parties of the country, to favor their scheme,” making payments to them under various spurious guises. As the report continued, “when such men … are employed to ‘collect statistics’ and write newspaper articles, everybody knows that it is not the labor which they perform, but the weight and influence of their name and character which is the main consideration for the money which is paid them.”

Even more troubling were the details of funds disbursed inside the capitol itself. One thousand dollars, a huge sum for the period, went to Abel R. Corbin, a clerk on the House Committee on Claims, for what the investigating committee called “his advice and assistance, and for the advantage which his official position gave him of ready access to members of the House.” The benefactor claimed this was “a mere trifling gratuity or present, by way of acknowledgement of sundry acts of kindness and advice received from Mr. Corbin during Mr. Stone’s stay in Washington.” This defense was somewhat undermined however by discovery of a letter from Stone to Corbin written following passage of the new tariff, in which the former stated “‘the labourer is worthy of his hire,’ and I enclose a check … for one thousand, in accordance with my understanding with you. You have fairly earned the money.” Ironically, unknown to Stone, Corbin had actually lobbied against the bill, after finding it not to his liking, though this did not prevent him from accepting the payment when it was offered. “Although the committee are not disposed to give Mr. Corbin all the credit which he claims for controlling the legislation of Congress on the most important measures of legislation affecting the revenue and finances of the country for the last ten years,” the investigators’ report dryly concluded, they were satisfied of his willingness to sell whatever influence he did possess to the highest bidder. Corbin would later marry the sister of President Ulysses S. Grant, and get caught up in another scandal when he abused his influence with the White House in colluding with speculators to corner the gold market in 1869.

None of the missing money could be proven to have ended up in the pockets of members of Congress, but there was certainly plenty of suspicion to go around. The Speaker of the House, Nathaniel P. Banks, who had shepherded the bill through the lower chamber, was revealed to have accepted $700 from Lawrence, Stone, & Co., but was cleared of any wrongdoing on the basis of his claim that the payment was a loan, which he still intended to repay, and was unrelated to the tariff. It was also alleged that New York congressman Orsamus B. Matteson (fig. 6) had told the manufacturers that there were twenty-five votes in the House that could be bought for $25,000; again, this charge proved impossible to corroborate, though it does not say much for Matteson’s character that he is the only member of the House ever to face two expulsion hearings on different charges, having previously been implicated in another lobbying scandal. “The inevitable Matteson had his finger in the pie, as usual,” noted one disgusted newspaper writer. As for the investigating committee, they concluded that the whole sorry episode “shows how the legislation of the country may be influenced by large masses of capital, concentrated in the hands of a few persons having a common interest, so as to benefit that interest at the expense of the great mass of the people.”

“One of the most unfortunate and alarming features of the politics of the day, is the prevalence of corruption among those who are selected by the people as their representatives and law-makers. It is impossible to avoid the conclusion that a monarch more powerful than any European sovereign, the Almighty Dollar, is yearly gaining new strength, as the real controlling power of far too much of the legislation of the country, whether Municipal, State, or National. … So far has this custom progressed that our legislative halls are thronged with professional vote-sellers. Nominally, there are lobby members, but really they sell out, at so much a head, some of the honourable members, as pigs are sold in the market.” This newspaper editorial, entitled “The Prevalence of Corruption,” was written not in 2016, as an accompaniment to Lawrence Lessig’s quixotic campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, but over 150 years earlier, on the eve of the Civil War. When Lessig speaks of the need “to fix our democracy first—to take it back from the billionaires and corporations, so we’d have a chance of addressing sensibly the host of critical problems that we face as a nation,” he confronts an issue that is not new to American politics, and that others have confronted before him. Whether the candidate who emerges triumphant from the current race for the White House will have the courage to confront that same issue, in an era when lobbyists are more numerous and more powerful than ever, remains very much in doubt.

Further Reading

Douglas E. Bowers, “From Logrolling to Corruption: The Development of Lobbying in Pennsylvania, 1815-1861,” Journal of the Early Republic 3 (Winter, 1983): 439-474.

Amy Handlin, ed. Dirty Deals? An Encyclopedia of Lobbying, Political Influence, and Corruption, 3 vols. (Santa Barbara, Calif., 2014).

OpenSecrets.Org (Website of the Center for Responsive Politics).

Jeffrey L. Pasley, “Private Access and Public Power: Gentility and Lobbying in the Early Congress,” in Kenneth R. Bowling and Donald R. Kennon, eds., The House and Senate in the 1790s: Petitioning, Lobbying, and Institutional Development (Athens, Ohio, 2002).

Carl E. Prince and Seth Taylor, “Daniel Webster, the Boston Associates, and the U.S. Government’s Role in the Industrializing Process, 1815-1830,” Journal of the Early Republic 2 (Autumn 1982): 283-299.

Mark W. Summers, The Plundering Generation: Corruption and the Crisis of the Union, 1849-1861 (Oxford, 1987).

This article originally appeared in issue 16.4 (September, 2016).

Daniel Peart is a lecturer in American history at Queen Mary University of London. His latest project explores the role that lobbying played in the making of U.S. tariff policy between the War of 1812 and the Civil War.