Until I heard this exchange between reporter Lesley Stahl and Smithsonian anthropologist Douglas Owsley I wondered why historians should concern themselves with the peculiar saga of Techamnish Oytpamanat (the Ancient One), better known in media circles as Kennewick Man. I knew those who were arguing over the remains of the nine-thousand-year-old man were talking about archaeology, biology, human migration, and the rights of Native Americans to claim as kin an individual who witnessed the murky dawn of human habitation of the Americas. But apparently, Owsley told me, they were also talking about “American history.” “[O]ur history.” According to Owsley and his colleagues, who have sued the government for access to the remains, they are fighting for nothing less than the right to pursue knowledge, to search for truth. Since Owsley has taken up the cause of curiosity, enlisting all disinterested seekers of truth in his battle, I figure historians should at least pause to consider which side of this court fight they might actually like to join.

The case is a complicated one. The plaintiffs, led by Oregon State anthropologist Robson Bonnichsen, have sued the government for the right to study the ancient remains. The government and the tribal claimants counter that, under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA), the bones are those of a Native American and, by rights, belong to the tribes. But the plaintiffs insist that Kennewick Man is too old to be claimed as kin by anyone now alive. The law, they say, simply cannot apply to anything so old. By extension the plaintiffs’ case suggests that if Kennewick Man cannot be said to belong to one group or tribe, he must somehow belong to all of us, to all humanity.

This sense of belonging to us all is, I think, what Douglas Owsley meant to explain to Lesley Stahl. As such comments suggest, when we talk about Kennewick Man, we are not talking only about American history, but about what might be called species history–the history of Homo sapiens in the Americas. Recovering the history of ancient humanity may in fact be an undertaking in which we all share an interest. But the case of Kennewick Man is teaching us that the pursuit of species history is troubled by the political and intellectual history of the last five hundred years.

For those of you who may have forgotten the story, Kennewick Man reappeared among us in the summer of 1996. Like so many celebrated archaeological finds, the discovery of his bones was an accident, pure and simple. On a hot July afternoon, two young men sneaked into the hydroplane races on the Columbia River near Kennewick, Washington. There on the banks of Lake Wallula, a man-made reservoir under the control of United States Army Corps of Engineers, they happened on a human skull. Figuring their grisly find would keep through an afternoon of boat racing, they stashed the head in the bushes and watched the meet. That night they delivered the skull to the county coroner, who promptly got in touch with an independent forensic anthropologist friend, James Chatters. Later Chatters and the coroner returned to the site and picked from the mud the bones of a nearly complete human skeleton.

At first Chatters was sure he had the remains of a long-dead Euro-American settler, a man who had come west some hundred and fifty years ago looking for a nice place to farm, or for gold and glory. But on closer examination, the forensic details contradicted Chatters’s original hunch.

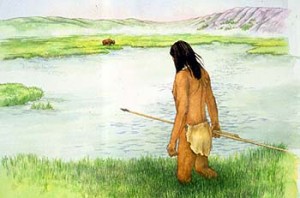

It was Chatters who literally put a face on Kennewick Man. The bones, he decided, did not belong to a Native American. The skull was just the wrong shape–long, not round. At first Chatters was sure he had the remains of a long-dead Euro-American settler, a man who had come west some hundred and fifty years ago looking for a nice place to farm, or for gold and glory. But on closer examination, the forensic details contradicted Chatters’s original hunch. For on his way west, it seemed, the poor pioneer had run into some hostile primitives; lodged in his right pelvic bone was a projectile point of the sort favored by Stone Age hunters. The Man had also survived a few broken ribs and a minor skull fracture. Curious to verify that the remains belonged to an ancient American and not to either an Oregon pioneer or a more recent victim of foul play, Chatters sent a small piece of bone off to a lab at the University of California, Riverside. To his surprise, the lab reported back that the bone was about eighty-four hundred years old, far older than he had suspected.

We have come upon only a handful of American skeletons this old, and Chatters no doubt recognized he had in his home laboratory a prize with enormous scientific potential. If he were to be the lucky one to publish findings on the remains, the skeleton might prove quite valuable to him professionally and personally. As it turned out, Chatters had little time to enjoy his treasure. Basking in the publicity of his sensational find (and no doubt cherishing the professional rewards it could bring), the aptly named Chatters started talking to the press. Instead of using the surprising lab report to question his initial assumptions about the skull’s European look, Chatters stuck to his first impression, reporting that he had found the skull of a man of European descent, an ancient American with caucasoid features.

Reporters ate it up. Suddenly, the old bones took on flesh and began to resemble British actor Patrick Stewart, best known as Captain Jean-Luc Picard of the starship Enterprise. (Others note a resemblance to the Ainu of northern Japan, more plausible kinsmen for ancient Americans.) In the popular press, Chatters’s “caucasoid,” a loosely descriptive term, hardened into the racial category, Caucasian. And before we knew it, we had the story of an ancient European (with a pretty brave heart) wandering around the Columbia Plateau some nine millennia ago.

The early flurry of media attention taught Chatters that he was on to a good thing, and he quickly contacted well-placed acquaintances at the Smithsonian, offering to share the fame likely to come to those able to solve the riddle of Kennewick Man. But in his pursuit of publicity, Chatters made a few mistakes. The bones, remember, were found on land under control of the Army Corps of Engineers. About discoveries on government land, NAGPRA is quite specific: local tribes must be notified of human remains found on federal land. Furthermore, any bones more than five hundred years old are presumed to be those of a Native American. We can excuse Chatters and the local coroner who first thought the remains those of an Oregon pioneer, but once Chatters learned the age of the remains, he should have alerted the local tribes, as NAGPRA clearly required.

NAGPRA, whose provisions Chatters disregarded at his peril, is an important piece of legislation. Without it, there would be no controversy over custody of Kennewick Man. Chatters could have spirited the bones off to his lab, studying them and publishing his findings more or less as he saw fit. But in 1990, Congress had passed a law that made such independent action illegal.

One story traces NAGPRA’s genesis to a mission to Washington in 1986 by William Tallbull to retrieve a sacred pipe taken from his Cheyenne people some hundred years earlier by the United States Army. Tallbull found the pipe at the Museum of Natural History, where he also discovered, quite by accident, storage bins containing the remains of some eighteen thousand individual Native Americans. Outraged, he took his case to Congress, where he found a sympathetic audience. While some museum professionals and archaeologists initially objected to a bill that mandated the return of human remains and sacred objects to tribal members, the law that finally passed represented, as Senator John McCain put it in 1990, a “true compromise” in the face of “very difficult and emotional issues . . . I believe this legislation effectively balances the interest of Native Americans in the rightful and respectful return of their ancestors with the interest of our Nation’s museums in maintaining our rich cultural heritage, the heritage of all American peoples.”

Of course, NAGPRA would affect not just “our Nation’s museums,” as McCain stated, but also archaeologists doing fieldwork and even little boys playing at skullduggery. Still, McCain was optimistic. And so, at least at first, were many archaeologists and museum professionals who accepted the opportunity NAGPRA offered to redefine their historically troubled relations with Native Americans. But behind many a compromise, I suspect, lurk sore losers. The story of Kennewick Man in court suggests that all were not content with the NAGPRA regulations that now governed museum holdings and archaeological digs. The law said that consultation and collaboration should precede independent inquiry, and to a few of the disgruntled, such provisions seemed to privilege Native claims over those of professional archaeologists and anthropologists.

Those determined to challenge the law recognized that among its weakest points was the assertion that what NAGPRA referred to as “cultural affiliation” would determine the disposition of a find as rare as the Kennewick skeleton. In effect, the plaintiffs’ case asks whether we can use “culture” to connect the present with the very remote past. What evidence establishes a convincing case for a cultural link between present-day tribes and a prehistoric wanderer? Is “cultural affiliation” an immutable connection? Could “cultural affiliation” trump a more scientific definition of inheritance, for example? In Bonnischen, et al. v. U.S., the anthropologist-plaintiffs–who would surely under other circumstances defend the importance of culture–ask whether the modes of behavior and belief that bind human beings into communities and link those communities through memory and ritual to their pasts can reach back into “prehistory.”

To counter, some, like the Denver repatriation coordinator Roger Echo-Hawk, insist that tribal memories do indeed stretch to the dawn of time. Echo-Hawk questions the assumptions that make it possible to divide history from prehistory, finding in stories told aloud and passed from generation to generation traces of cultural memories that reach further into the past than we have heretofore imagined. Traditional stories may not look like good evidence to the scientifically trained plaintiffs, but NAGPRA allows the courts to consider oral traditions and sacred beliefs as evidence of cultural affiliation. Much more than a battle over bones, then, the case amounts to nothing less than a contest between two different ways of looking at the world, two different ways of thinking about facts and evidence.

But ultimately, such competing philosophies of culture may be less important to the Kennewick case than a simple matter of law that regulates how such discoveries are to be handled. Neither Chatters nor his friend the coroner bothered to contact the tribes who might be very interested in Kennewick Man: the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Yakama Indian Nation, the Nez Percé, the Wanapum band, and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, all still resident in eastern Washington. But partly with Chatters’s help, the find generated publicity. And the first printed report in the Tri-City Herald, the region’s local paper, prompted a representative of the Umatilla tribe to contact federal authorities. The law was clear. The skeleton was the property of the tribes.

With Native claimants in the picture, Chatters’s dream of professional good fortune evaporated. To be sure, Chatters had gotten a lot of publicity, but his luck started to turn. Much to Chatters’s dismay, agents from the Army Corps of Engineers arrived at his house and took the bones. The government then set about figuring out how to return the remains to the Native claimants–the Umatilla, the Nez Percé, the Yakama, the Wanapum, and the Colville–all of whom, whether by dint of history, tradition, culture, or geography, thought they might be related to the Ancient One. In September 1996, less than two months after the boat race, the Corps of Engineers published an official “Notice of Intent to Repatriate” Kennewick Man’s remains, as NAGPRA said they must. This time, it was not a contending tribal group that challenged repatriation, but a group of eight anthropologists, often identified as “eminent” or “prominent” in press reports. Under the lead of Robson Bonnichsen, head of the privately funded Center for the Study of First Americans at Oregon State University, the anthropologists sued to prevent repatriation. They contended, as Owsley would later suggest to Lesley Stahl, that the Kennewick remains were too old to belong to anyone in particular and therefore must belong to everyone. Furthermore, even if the man did have descendents among the tribes of the Columbia Plateau, the only way to find them would be through the kinds of genetic tests some of the tribal claimants sought to prevent.

What if Kennewick Man was a European wanderer and not a Native American at all? What if Kennewick Man has no descendants? What if neither blood nor culture ties him to a contemporary tribe?

It is tempting to turn the case of Kennewick Man either into a contest between selfless scientists and shortsighted Native Americans, or a struggle between selfish anthropologists and right-minded Native claimants. But both constructions risk simplifying matters that are considerably more complex. The anthropologists are perhaps right to question the assumption that we can easily trace a community’s ancestry far into the past, but they should not be surprised that many will dispute their contention that they speak from neutral ground and for all humanity. The checkered history of their discipline haunts the plaintiffs’ case. It is also apparent that their large claims about a noble and disinterested pursuit of truth serve the much smaller purposes of challenging NAGPRA. Antone Minthorn, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, characterized the struggle over Kennewick Man as a struggle over the interpretation and application of NAGPRA. “It is not science versus religion,” Minthorn wrote, “it is science versus the law.”

While this custody fight, of sorts, continues in the U.S. District Court in Portland in the form of Bonnichsen, et al. v. U.S., the remains of Kennewick Man are locked away for safe keeping in the basement of the Thomas Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture In January 2000, U.S. magistrate John Jelderks decided that Kennewick Man was a Native American, as defined by NAGPRA. Left open, however, was how the law governing Native American remains should apply in the case. To help determine the proper “cultural affiliation” for the remains, the court ordered the genetic tests the tribes objected to in the first place.

Labs are still struggling to produce results, but the Interior Department recently determined that the bones should be turned over to the tribes. According to Secretary Bruce Babbitt, geography and oral tradition establish “a reasonable link between these remains and present-day Indian tribe claimants.” “The oral tradition evidence,” he writes, “reveals that the claimant Indian tribes possess similar traditional histories that relate to the Columbia Plateau’s past landscape. The oral tradition evidence lacks any reference to a migration of people into or out of the Columbia Plateau.” Now that the Interior Department has weighed in, accepting as good evidence the kinds of information the plaintiff-scientists surely consider suspect, the case is back in federal court.

Regardless of whether Interior Department policy, a decision in the courts, or DNA testing ultimately seals the fate of Kennewick Man, the issues raised in the battle of the bones will continue to ripple outward. The case has spilled out of the courts and into the culture at large because it forces us to think about how we sort human beings. What does it mean to label Kennewick Man a Native American? How far back in time can we trace a cultural lineage? How far into the past can we extend our contemporary racial categories? On some of these issues, the language of NAGPRA is simple enough. The law states: “‘Native American’ means of, or relating to, a tribe, or culture that is indigenous to the United States.” In practice, any remains from the period before European contact are assumed to be Native American.

This assumption is precisely why the strange looking Kennewick Man seemed to offer such a good opportunity for discontented anthropologists to challenge the law. What if Kennewick Man was a European wanderer and not a Native American at all? What if Kennewick Man has no descendants? What if neither blood nor culture ties him to a contemporary tribe? Raising such complicated questions–questions that wreak havoc with NAGPRA’s neat categories–serves the interests of the plaintiffs. Who better to claim the odd orphan, their suit suggests, than the anthropologists, who have nothing but the best interests of science, and by extension of all humanity, at heart?

And this skeleton, the plaintiffs tell us, could be really important. In the court of public opinion, the plaintiffs bolster their case by churning up renewed curiosity about the peopling of the Americas. Most of us learned in grade school that near the end of the last ice age, around twelve thousand years ago, human beings followed game from Asia into the Americas, crossing the Bering Strait on a land bridge. But recent archaeological findings suggest human habitation far older than initially suspected. A Bering land bridge and an ice-free corridor down the center of the continent may have been available more than once, and humans may have migrated in waves.

From some newer studies an even more complicated picture of multiple coastal migrations seems to be emerging. According to the innocent-sounding organization, Friends of America’s Past, “Exciting new scientific theories about the peopling of the Americas are changing our understanding of the past.” Kennewick Man promises to add an “important piece to this puzzle.” Outraged, Friends of America’s Past continue, “This unique, nearly complete skeleton was almost reburied without any study.”

In fact, “Friends of America’s Past: A nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting and advancing the rights of scientists and the public to learn about America’s past,” is an organization dedicated to raising funds to help the plaintiffs in Bonnichsen, et al., v. U.S. pursue their challenge to NAGPRA. It is hardly surprising that on their own Website they cast themselves in heroic terms, as valiant Davids struggling against the Goliath of the federal government, a far better villain for their piece than the small tribes of eastern Washington. How ironic as well that for once the government is “for” the Indians and “against” the academics. “It’s time to stand up for the right to learn about the past,” the Friends of America’s Past write. “We all share the past–no one owns it. Imagine if a few people could decide by whom, when, and how evidence from the past can be studied. Is this the legacy we want to leave to future generations?” Of course it isn’t.

What’s more, in the plaintiffs’ scenario, the tribes are not only religious reactionaries, they are guarding ill-gotten privileges. And the mainstream media, particularly reporters covering the story for CBS’s 60 Minutes in October 1998, readily accepted the plaintiffs’ portrait of their opponents. The story 60 Minutes aired underlined the plaintiffs’ contentions: over images of Indian revival–a powwow and a casino–reporter Lesley Stahl repeated Chatters’s suspicion that the “tribes’ fight against further testing of Kennewick Man is based largely on fear, fear that if someone else was here before they were, their status as sovereign nations and all that comes with it–treaty rights and lucrative casinos, like this one on the Umatilla Reservation–could be at risk.”

Of course, as Stahl herself noted, “The Indians say that’s nonsense.” And the Indians are right: under the law, the claim that treaty rights and casinos depend on Native American’s status as “first peoples” is indeed nonsense. As the Umatillas’ Minthorn put it, “The outcome of this case has no legal bearing whatsoever on tribal treaties and tribal sovereignty.” His people, he explains, are not motivated by money, but rather by a desire to defend NAGPRA and by a strong belief that human remains deserve the dignity of permanent burial. Native beliefs about death, burial, and the afterlife are as diverse as the hundreds of cultural traditions they represent, but many tribes do maintain a particular respect for the remains of the dead. For once a law passed by the United States Congress gives the tribes an opportunity to act on their cultural beliefs.

Whatever the merits of the plaintiffs’ case, their position is tainted by their apparent kinship with generations of greedy whites who ignored laws and treaties when laws and treaties thwarted their plans. To back their legal challenge, the plaintiffs have resuscitated some troubling arguments: they hint that Kennewick Man may have been here before the ancestors of contemporary Native Americans. Scholars aired such ideas in the early 1800s, and something pernicious lingers in the assertion that Native Americans came late to the continent. The first generation of American archaeologists who tried to solve the mysteries of the Mound Builders decided that the architectural wonders of ancient America were built by people unrelated to the Indians they knew. Early nineteenth-century scholars imagined a sophisticated and peaceful people eliminated by the violent forebears of the Indians they now fought.

Taken to the extreme, images of battles among the ancients cast a righteous glow over white violence against Native peoples: nineteenth-century white settlers fought in the name of the late, vanquished Mound Builders–the true and rightful owners of the continent. In a milder form, such ideas perhaps eased whatever qualms of conscience came with conquest: when all was said and done, Indians had no better claims to their lands than the European and American usurpers who came after them. This legacy of disputes over treaty rights and first settlement complicates the simple neutrality that Owsley, Bonnichsen, and the rest of the Kennewick plaintiffs seem so ready to adopt. Perhaps in an ideal world, science is disinterested. Scientists, however, rarely are.

It is not hard to understand why the plaintiffs would like to work on the Kennewick remains. We have happened on only a handful of American bones this old, and scientists are sure Kennewick Man can answer many questions about ancient America. Any anthropologist who solves the riddles of the bones–riddles about everything from ancient diet to the origins of American society–will surely receive accolades from the profession and the public. The plaintiffs, who unfortunately missed the opportunities for collaboration and compromise that NAGPRA encourages, fear that repatriation means reburial. They suspect that once the bones of the Ancient One return to the tribes, whatever information they contain will be lost forever. Lost to the plaintiffs, perhaps. But who is to say that an anthropology reconceived in consideration of Native concerns will not extract plenty of information from old bones?

Yet on some level, I sympathize with the plaintiffs’ position. I acknowledge I too experienced a twinge of regret over the repatriation of a collection of Native American skulls, and not a one of them promised to shed light on anything so momentous as who first peopled the Americas. I was just surprised by how beautiful the skulls were and by how much the skulls seemed to tell us, not about the individuals they once belonged to, but about the nineteenth-century Americans who collected them. Last summer I began reading the correspondence of the American naturalist Samuel George Morton. I decided to track down the remnants of the skull collection he built in the 1830s and 1840s. By the time Morton died in 1851, the scientist had gathered in more than one thousand human crania, the bulk of them the skulls of Native Americans. Morton rarely left his native Philadelphia, but with the help of amateur naturalists and doctors in the frontier army, the shelves of his study filled with skulls from the battlefields of Florida and the American West and spoils from the burial grounds of tribes forced off ancestral lands. Morton measured his skulls, but he also cleaned, polished, varnished, and labeled them and then put them on display, inviting the public to visit his collection, free of charge, on Tuesdays and Saturdays.

On his death, Morton’s friends donated his collection to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. In 1893, the academy sent forty of the Native American skulls to Madrid as part of the official United States entry in the exposition commemorating the four-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of the New World. Judges awarded Morton’s crania a silver medal. But when the skulls were returned to the United States, tastes had apparently changed, and academy curators decided not to put the bones back on display. The remnants of Morton’s collection eventually wound up in the storerooms of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The old skulls are now shrouded in bubble-wrap and sealed in plastic containers, awaiting repatriation.

To protect their rights–among them the right to dispose of their dead according to their own traditions, and the right to explore their history according to their own definitions–the tribes have taken a strong position in the dispute. For once, the law is on their side.

Morton’s collection lost its coherence more than a century ago, but I suspect the beauty of the skulls may have motivated him every bit as much as pure science. Morton collected all sorts of heads–not just the heads of humans, but the heads of birds, mammals, and apes. Viewed from one angle, his cranial collection prompted visitors to consider the small physical things that separated human beings from the rest of creation. While Morton presented his collection as a portrait of the continent’s past inhabitants, no doubt visitors saw in the bony forms, the hollow sockets, the toothy grins reminders of their certain future.

But Morton also sorted his skulls by race, measuring the cranial capacity of each of the great families of man. No surprise that white men like him turned out to have the best and biggest heads. His two ways of looking as skulls–as objects that represent humanity and as objects that represent specific races–approximate the two sides in the struggle over Kennewick Man. Should Kennewick Man be made to shed light on a common story of all humanity? Or should he be reserved to a chapter in the history of a particular group?

Morton’s collection, of course, has no direct bearing on the case of Kennewick Man. But when I began to look at the correspondence that accompanied the skulls to Philadelphia, I understood why Native communities feel so strongly about the principles of NAGPRA. Morton measured his skulls, hoping to discover in them an index of racial difference. For his empirical project to work, he needed to know who was who among his heads, and so each skull came with a pedigree of sorts, a provenance laid down by Morton’s friends in the field. Morton’s agents told him how they came by the heads they sent him. Describing their collecting, they detailed the violence behind the scientist’s tranquil speculations. One man collected two “fine” Seminole skulls left unburied after the battle of Lake Okee-Chobee. He apologized that “only two out of twelve killed . . . could be taken the others being very offensive.” A correspondent from Indiana promised to procure for Morton “the skulls of Chapodicac and Rushynble both eminent chiefs,” just “as soon as the Indians are removed from our neighborhood which will be this Fall.” And Morton’s memoirist described one man who “exposed his life robbing an Indian burial place in Oregon, and carried his spoils for two weeks in his pack in highly unsavory condition, and when discovery would have involved danger and probably death.”

Are the plaintiffs in Bonnichsen, et al. v. U.S. the direct descendants of Samuel Morton and his headhunting friends? Yes and no. On the one hand, Bonnichsen and his associates had nothing to do with Kennewick Man’s death. As the plaintiffs contend, his life so predates the disputes NAGPRA was designed to settle that it seems absurd to subject his remains to regulations devised to correct excesses of nineteenth- and twentieth-century science. But then again, Morton is a father of American physical anthropology. Perhaps in the Kennewick case, we witness a moment when the sins of the father are indeed visited on the sons. Little wonder that an atmosphere of hostility and mistrust surrounds the case.

The plaintiffs in the Kennewick case have used the media to create an artificially polarized situation, pitting enlightened professionals against narrow-minded reactionaries, Western science against Native mumbo jumbo. But, as I have tried to suggest, the plaintiffs’ claim to the moral and intellectual high ground is subject to question. So is their claim to speak for science and the unencumbered pursuit of truth.

For one thing, the plaintiffs simply do not represent the entire range of opinion in the community of “enlightened” professionals. Both Keith Kintigh, professor of archaeology at Arizona State University and president of the Society for American Archaeology, and David Hurst Thomas, curator of anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, have expressed support for NAGPRA. They see the law as an invitation to reinvent their profession, as an occasion to replace the racist arrogance that characterized old projects, like Morton’s, with cooperation and consultation. Thomas suggests we need to take a broad view of the issues involved in the Kennewick case. It may be easy, as the media have done, to tell this story as a struggle between disinterested professionals and unenlightened Indians, but “[u]ltimately,” Thomas writes, echoing sentiments expressed by Umatilla chairman Minthorn, “the Kennewick dispute is not a matter of science v. religion, or even Indians v. scientists. At its heart, the matter of the Kennewick skeleton involves political power and property rights.” To protect their rights–among them the right to dispose of their dead according to their own traditions, and the right to explore their history according to their own definitions–the tribes have taken a strong position in the dispute. For once, the law is on their side.

Mr. Owsley, then, may be right after all. The Kennewick case is about “American history.” But perhaps not quite in the way he intended. Our route to the ancient history of the continent is troubled by the history of the last five hundred years. Past relationships haunt the current dispute. Sometime this fall, Magistrate Jelderks will decide how best to dispose of the ancient remains. When the case is closed, Kennewick Man likely will have taught us nearly as much about who we are as a people as about who the people were who dwelled on the banks of the Columbia River nine thousand years ago.

Further Reading: A Note about Kennewick Man on and off the Web

Kennewick Man emerged from the mud of the Columbia River in 1996, only to be caught in the strands of the World Wide Web. To write this piece for Common-place I decided to play the student-researcher and try to reconstruct this story by following Kennewick Man all over the Web. Pursuing Kennewick Man, a sort of model citizen of cyberspace, made me dizzy: there seemed an endless supply of information, an infinite number of links. Consider that the search engine Google lists some 11,100 sites for Kennewick Man and another ninety-three for those inclined to call him Kenniwick Man. The contending parties in the suit (the university-based anthropologists, professional archaeologists, the tribes, the National Park Service, the museums, the newspapers and the networks) maintain Websites with pages devoted to Kennewick Man. The Burke Museum touts its celebrated skeleton on its home page. On your visit to the virtual museum you can even attend a symposium on Kennewick Man and listen to brief presentations by several of the players in the story.

For the local media, the story has also been a good thing. Tri-City Herald maintains a Kennewick Man Virtual Interpretive Center where you can review the paper’s coverage of the case and even sign up to receive by e-mail the breaking news on Kennewick Man. You can also read the story from the point of view of the Archaeological Institute of America. Or from “America’s Leading Indian News Source,” Indian Country. Or from the Journal of Indian Justice. By following the links offered by Friends of America’s Past, you can even give money to the plaintiffs.

When I found the Website that asked for money, I knew I was getting in over my head, and turned to the historian’s more traditional printed sources as an antidote. I needed a community of scholars to help sort out the voices on the Web. Last spring, I attended a conference at Harvard’s Peabody Museum on the tenth anniversary of NAGPRA and read an article by Scott L. Malcomson, “The Color of Bones: How a 9,000-year-old Skeleton Called Kennewick Man Sparked the Strangest Case of Racial Profiling Yet,” New York Times Magazine (April 2, 2000): 40-45, and a book by David Hurst Thomas, Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archaeology and the Battle for Native American Identity (New York, 2000). I also found useful Roger Echo-Hawk’s “Forging a New Ancient History for Native America,” in Native Americans and Archaeologists: Stepping Stones to a Common Ground, eds. Nina Swidler, Kurt E. Dongoske, Roger Anyon, and Alan S. Downer (Walnut Creek, Calif., 1997): 88-102.

Perhaps the best single source on Kennewick Man is Roger Downey’s recent Riddle of the Bones: Politics, Science, Race, and the Story of Kennewick Man (New York, 2000). Downey, a reporter who has been following the story for the “alternative” Seattle Weekly, sorted out the figures in the case, offering his explanations for their various positions. You can read some of Downey’s original columns online. But as the workings of the Web would lead us to expect, Downey has detractors in cyberspace. In his account, he cast Kennewick Man’s self-proclaimed Norse kinsmen, the Asatru Folk Assembly, as the New Age buffoons of the story. And not exactly as harmless buffoons, either. Although the followers of Odin dropped their claim to the remains of the Ancient One, Downey paused to note ties of some Asatru leaders to the Afrikaner Resistance Movement and the white supremacist Church of the Creator. The Odinists struck back, using Amazon’s readers’ forum to denounce Downey’s book as “blatent [sic] lies.” A reader signing herself “maryscats” tried to give the book no stars at all: Amazon, to her consternation, insisted she give it at least one.

I wish I could say that my pursuit of Kennewick Man on the Web turned me into an adept electronic researcher. Not quite. I confess I reverted to form and consumed nearly a ream of paper printing out the contents of the Websites I visited. In some cases this was useful (particularly with the reports on the Kennewick remains compiled by National Park Service archaeologist Francis P. McManamon but in others hardly necessary. I was also left with the impression that even though this story is a relatively manageable one, I would never be able to visit every Website devoted to it or to assess every opinion expressed on it.

Poor Kennewick Man: nine thousand years of repose interrupted by such a lot of chatter.

This article originally appeared in issue 1.2 (January, 2001).

Ann Fabian teaches American studies and history at Rutgers University. Her most recent book is The Unvarnished Truth, a study of personal narratives. She is working on a new book about Samuel George Morton and his collection of skulls.