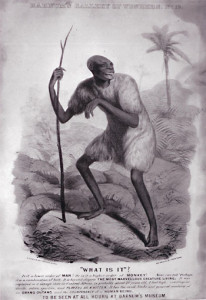

A Currier & Ives lithograph from the early 1860s captioned “WHAT IS IT? OR ‘MAN MONKEY’” provides a telling illustration of nineteenth-century curiosity. Its title refers to the diminutive, stooped, black figure standing in the center of the image. But it might also describe the response of the white spectators who surround him and are invited to question the nature of this “most singular animal” combining “characteristics of both the HUMAN and BRUTE species.” The image thus hints at the kinds of things the U.S. public would have considered curious, as well as the ways the public expressed its curiosity. In the nineteenth century, the showman P. T. Barnum transformed the longstanding practice of exhibiting human curiosities into a profitable business. As the lithograph promoting the attractions in Barnum’s American Museum demonstrates, freak shows were considered acceptable entertainment for consumers from across the social spectrum, including women and children. It also suggests that human exhibitions provided opportunities for exchange between viewer and spectacle. In contrast to displays of inanimate objects, living curiosities were expected to interact with the customers who paid to see them.

In the lithograph, the spectators stand close to the What Is It? but they still maintain a respectful distance; they look but they do not touch. This scene differs markedly from accounts of white working-class and African American spectators, who had little concern for the polite conventions obeyed by more elite museum goers. Their more rowdy displays of curiosity were particularly volatile in the case of racial exhibits like the What Is It?, which raised questions about the humanity of black people precisely at the moment when the U.S was poised on the verge of civil war over the question of slavery. The What Is It? was advertised as a hybrid of man and monkey discovered in a distant and exotic place that was “the wilds of California” when the exhibit toured in London, but was more often said to have been discovered in Africa. Although the creature was often represented as “docile . . . and playful as a kitten,” he belonged to roughly the same genre as the more menacing wild men, savages, and cannibals promoted by Barnum and other showmen of the time.

The wild man was a stock sideshow personality, along with other common types such as fat ladies, tattooed people, giants, and midgets. During the period of their greatest popularity (roughly 1840-1940), freak shows consistently trafficked in representations of people of color that combined pedagogy and entertainment, pseudoscientific jargon, and fantastic hyperbole. In doing so, they offered simplified answers to the pressing concerns about race that would have preoccupied their predominantly white audiences, already anxious about slavery and its aftermath, the great waves of seemingly inassimilable immigrants, and imperial expansion. Freak show savages offered a simple equation of race with monstrous bodily deviance. As the black body in front of them was transformed into a hypervisible spectacle, audience members could believe that they in turn blended together into a transparent, homogenous whiteness. Those most anxious about their own status as citizens applauded the reassuring vision of nonwhite bodies that absolutely could not be assimilated.

Indeed, whether presented as foolish and docile or wild with rage and bloodlust, the unassimilability of the dark-skinned body was the dominant message conveyed by the racial freak. As W.C. Thompson explained in his 1905 memoir, On the Road with a Circus, “[T]he original circus wild man, the denizen of Borneo, was white, but his successors have almost invariably had dark skins.” The predictability of such connections between wildness and dark skin was confirmed by journalist Scott Hart, who noted as late as 1946 in the popular miscellany Coronet, “[M]ost Wild Men from Borneo are amiable Negro boys from about the circus lot who are trained to growl, flash a set of fake tusks and eat raw meat . . . The Wild Man is always from Borneo. The Bear Woman is from the darkest wilds of Africa. The Pinheaded Man is from the jungle-ridden regions of Somewhere.” The formulaic print “ethnographies” that often accompanied these exhibits associated wildness with remote geographical locales. An undated pamphlet on Waino and Plutano, the Wild Men of Borneo who were exhibited between 1852 and 1905, for example, informed the reader, “Borneo is an island so large that England, Ireland, and Scotland might be set down in the middle of it. The interior of this vast island is a dense forest, inhabited by a race of humanity very little different from the animal creation.” Couched in pedagogical terms, such explanatory narratives perpetuated commonly held assumptions about the physical and cultural otherness of non-Western and non-white people.

In contrast to the presentation of physically disabled freaks, who during the course of their performance might answer questions, lecture the audience about their unusual bodies, or demonstrate their capacity to perform everyday activities, the wild man was deliberately inarticulate, his snarls and roars a sign of his absolute inability to communicate through language. “I was all stripped ‘cept around the middle and wore a claw necklace; had to make out as if I couldn’t talk. ‘Twas mighty tiresome to howl and grin all day,” recalled a former wild man quoted in Thompson’s memoir. Sometimes eating raw meat, biting the heads off live animals, or drinking blood, the wild man’s voracious and indiscriminate appetite epitomized western audiences’ understanding of “savage.” Often described in the terms of popular evolutionary science as a “missing link,” wild men (including the docile What Is It?) were said to come from a lost species located somewhere on the developmental chain between human and beast. While such acts were a regular part of low-budget traveling carnivals, they were equally popular in more reputable venues such as World’s Fairs and museums and among middle-class audiences such as the group in the lithograph.

Authenticity was always an important part of the freak show’s promotional rhetoric, which advertised exhibits as LIVE! TRUE! REAL! GENUINE! Despite such hyperbolic claims of veracity, the exotic act was the most easily and regularly fabricated of all attractions. More often than not, those advertised as Zulu warriors, Wild Men from Borneo, and Dahomeans were actually people of color from local urban centers. Although a number of men played the part of Barnum’s What Is It?, the most famous and longstanding was William Henry Johnson, a developmentally disabled black man from New Jersey. The journalist William C. Fitzgerald noted the financial benefits of such fraudulence in an 1897 Strand Magazine article on side shows: “Certainly it is far easier and cheaper to engage and ‘fit-up’ as the ‘Cuban Wonder’ an astute individual from the New York slums, than to send costly missions to the Pearl of the Antilles in search of human curiosities.” The memoirs of former sideshow managers and employees are unapologetic about the fabrication of ethnographic freaks. Indeed, the creation of a wild man is a recurrent chapter in the formulaic genre of the carnival memoir. Hart told the following story:

On a platform before the tent a tense, narrow-cheeked man related how the unfortunate individual from Borneo knew the whereabouts of neither father, mother, nor home, and that five thousand dollars would be paid anyone providing such information. Inside the tent, a fat rural woman said, “Oh, ain’t that awful!” A child asked, “You reckon he can get out?” But when dinnertime came, the Wild Man was taken to meet a distinguished local circus fan and his wife. In the ensuing pleasantries, he created a very happy social impression. With professional awareness, however, the Wild Man failed to mention that he came from South Carolina.

Hart reveled in the discrepancy between the exhibit’s deliberately mystified promotional rhetoric and the mundane, but quite respectable, activities of the Wild Man upon leaving the display platform. But other stories demonstrated a less salutary arrangement between performers and their managers. Thompson described the career of Calvin Bird, “a negro who hailed from Pearson, GA [who] toured most of the country, mystifying all who saw him and sending them away impressed with a conviction that he was all he was represented to be. Not until he appeared at a Syracuse hospital with a request that his horns be removed was the secret of his unnatural appearance disclosed. Under his scalp was found inserted a silver plate, in which stood two standards. In these, when he was on exhibition, Bird screwed two goat horns.” In contrast to the comfortable arrangement between Hart’s wild man and his promoters, Bird suffered bodily harm for the sake of his act, the victim of abusive surgeons and greedy showmen. Bird’s harrowing experience led Thompson to conclude, “[T]he life of the professional wild man is an unhappy one at best.”

Such anecdotal evidence bespeaks the pragmatic, and often cruel, opportunism of sideshow managers, who cared only about the lucrative consequences of maintaining a steady supply of unique and varied attractions. Accounts of their fraudulence are numerous and unsurprising. After all, it was the showman’s job to create illusions that amused and deceived his customers, and the wild man conformed to prevailing beliefs about racial inferiority. The standard was set by P. T. Barnum, who began his career in 1835 by exhibiting a racial freak, the elderly, disabled slave named Joice Heth who claimed to be the 161-year-old nurse of George Washington. A black woman whose body was contorted with age and years of hard labor was easily transformed into a sensation through Barnum’s skillful publicity campaign. When an autopsy following Heth’s death revealed her to be no more than eighty, Barnum deflected controversy by professing himself the victim of a hoax devised by Heth and her former owners. Barnum’s autobiographical writings provide different and somewhat contradictory accounts of these events, but they are consistently uninterested in proving that Heth was what she claimed to be. In some versions, Barnum conspires with Heth to deceive the public, while in others he is innocent, but in each version he establishes humbug as the rule rather than the exception in the showman’s trade.

These examples attest to the discrepancy between black actor and stage persona. But while it is not particularly surprising to find that racial freaks were actually local people of color tricked out in costume, the audiences’ role defies our expectation: rather than credulous, audiences seemed rarely to believe what they saw. For instance, having viewed the What is It? at Barnum’s Museum in 1854, the New York lawyer and diarist George Templeton Strong opined, “Some say it’s an advanced chimpanzee, others that it’s a cross between nigger and baboon. But it seems to me clearly an idiotic negro dwarf, raised, perhaps, in Alabama or Virginia. The showman’s story of capture (with three other specimens that died) by a party in pursuit of the gorilla on the western coast of Africa is probably bosh.” Strong distinguished himself from more credulous observers by describing the showman’s fantastic account of peril and adventure as “bosh.”

Such skepticism was common among diverse groups of patrons, but the most striking responses were registered by black spectators. In numerous instances, African Americans looked with suspicion and disbelief at racist performances, refused to enter into their fiction, and loudly enjoined the audience into collective incredulity. In his 1913 biography, circus veteran George Middleton wrote, “In the side show we have a big negro whom we had fitted up with rings in his nose, a leopard skin, some assagais and a large shield made out of cows’ skin. While he was sitting on stage in the side show, along came two negro women and remarked, ‘See that nigger over there? He ain’t no Zulu, that’s Bill Jackson. He worked over here at Camden on the dock. I seen that nigger often.’ Poor old Bill Jackson was as uneasy as if he was sitting on needles, holding the shield between him and the two negro women.”

The women in Middleton’s anecdote disrupted the exhibition by speaking directly to the stage. The gesture of recognition–”I know you!”–dispelled the illusion of the wild man’s absolute otherness, relocating him within the community of onlookers. Instead of a Zulu, he was Bill Jackson; rather than hailing from Africa, he was a dock worker from New Jersey. The account humorously transforms the shield intended as a sign of tribal savagery into a barrier to protect the guilty man from the female customers he was supposed to terrify.

Such examples invite us to turn from an analysis of the content of freak exhibition to questions of spectatorship. The racism of wild men and cannibal acts was crude and obvious, but why were audiences so ready to interrupt these performances? The freak show implicitly situated the viewer in a particular relationship to its content; however the response of actual spectators did not always conform to structural expectations. In the scenes I have described, the cry of recognition utterly disrupted the action taking place onstage and provoked the audience to join in a ritual of communal disbelief. It was impossible for the wild man to continue beyond that moment, for his act depended on the illusion of his absolute inscrutability. Only during a live encounter can the viewer’s response register with and alter the course of the dramatic action. An important ingredient in the audience’s enjoyment of freak shows seems to have been precisely this capacity to actively deconstruct the visual evidence presented to them. The combination of interruption, misidentification, and the possibility of fraudulence contributed considerably to the show’s appeal.

The pleasures of unmasking were part of a broader nineteenth-century preoccupation with the figure of the confidence man, whose reliance on trickery and deception was the unsavory counterpart to the Horatio Alger story of legitimate success gained through hard work and ingenuity. Barnum’s hoaxes ingenuously tapped into the public appreciation for the pleasures of questioning, debate, and evaluation. Ferreting out deception at the freak show doubtless filled audiences with satisfaction in their ability to distinguish between a scam and the real thing. George Templeton Strong took manifest pride in recognizing the What is It? as an ordinary African American and not a missing link. But even more striking were the scenes of recognition that addressed racial boundaries and identifications among African Americans, who uniquely stood on both sides of the stage as viewers and performers. A black audience contemplating the spectacle of a black man performing as an African savage would have a particularly savvy understanding of the slippery nature of theatrical representation. To hail the savage as “one of us” would be unacceptable because it threatened to equate African American spectators with the professed barbarism of Africa. But to stop the savage performer in his tracks gave the lie to that equation and, in the process, substantiated the power of the black “gaze”: a subversive rejection of the freak show’s conventional wisdom.

Revisiting these anecdotes tells us something about nineteenth-century curiosity, but also about our own attitudes towards spectatorship, consumption, and desire. While we no longer exhibit people of color as freaks, white audiences continue to enjoy the spectacle of African American basketball players, dancers, and musicians. Black spectators still confront the dilemmas of identification when they see black film and TV actors relegated to idiotic, exaggerated, or marginal roles. Greater access to media industries has enabled black comedians, filmmakers, actors, and activists to respond critically to racial stereotypes. At the same time, contemporary spectacles are far more carefully choreographed and insulated against the kinds of spontaneous outbursts that disrupted nineteenth-century performances. Looking to the past reminds us that, while curiosity may remain a constant, its forms and objects change over time. We may also realize the importance of focusing our own curious gaze not only on the objects, but on the complex responses of the onlooker who contemplates them.

Further Reading:

For more academic studies of the freak show, see Rachel Adams, Sideshow U.S.A.: Freaks and the American Cultural Imagination (Chicago, 2001); Robert Bogdan, Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit (Chicago, 1985); Leonard Cassuto, The Inhuman Race: The Racial Grotesque in American Literature and Culture (New York, 1997); James Cook Jr. The Arts of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum (Cambridge, 2001); Andrea Stulman Dennett, Weird and Wonderful: The Dime Museum in America (New York, 1997); Bernth Lindfors, ed., Africans on Stage: Studies in Ethnological Show Business (Bloomington, 1999) and “P. T. Barnum and Africa,” Studies in Popular Culture 7 (1984); Robert Rydell, All the World’s A Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916 (Chicago, 1984); Rosemarie Garland Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture (New York, 1996) and Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (New York, 1996). Fredrick Drimmer’s Very Special People (New York, 1983); Daniel Mannix’s Freaks: We Who Are Not As Others (San Francisco, 1990); and James Taylor and Kathleen Kotcher’s Shocked and Amazed: On and Off the Midway (Gilforld, Conn., 2002) are extensively illustrated, readable overviews written from the perspective of freak show fans. On the life and career of P. T. Barnum, see Bluford Adams, E Pluribus Barnum: The Great Showman and the Making of U.S. Popular Culture (Minneapolis, 1997); Neil Harris, Humbug: The Art of P. T. Barnum (Chicago, 1973); Philip B. Kunhardt Jr., Philip B. Kunhardt III, Peter W. Kunhardt, P. T. Barnum: America’s Greatest Showman (New York, 1995); Benjamin Reiss, The Showman and the Slave: Race, Death, and Memory in Barnum’s America (Cambridge, 2001); A.H. Saxton, P. T. Barnum: The Legend and the Man (New York, 1989); and Barnum’s own autobiography, Struggles and Triumphs (1869; rpt. New York, 1970).

This article originally appeared in issue 4.2 (January, 2004).

Rachel Adams is associate professor of English at Columbia University.