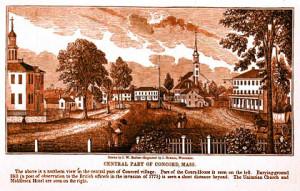

Concord, Massachusetts, is often portrayed as the quintessential New England town, and it is easy to understand why. Founded in 1635 as the first Puritan settlement above tidewater, the town appears connected to its past, even after nearly 370 years of growth and change. The historic center, which has evolved from the nucleated village planted by the original English settlers, still anchors the town. Colonial and early nineteenth-century houses line the same road that the king’s troops took into the village on the fateful nineteenth of April 1775. Visitors today pass many of the sights–the Greek Revival Unitarian Meetinghouse, the hill burial ground, the Wright Tavern, the Colonial Inn, the Town Hall, the cluster of shops and offices around the common and the milldam–that were familiar in the era of the Transcendentalists. Walk a mile or so in any direction, and you can enjoy the natural beauty of a landscape that seems miraculously to have escaped the ravages of suburban development. Early in the morning or in midwinter at Walden Pond, you can imagine yourself as solitary as Thoreau in his cabin. Concord encourages such illusions. It suggests rootedness, authenticity, an organic sense of place rarely found in the contemporary United States. No wonder the New York Times recently recommended the town for a weekend getaway: “Concord,” it declared, “is no Colonial Williamsburg.”

In these adulatory terms, Concord has been celebrated for a century and a half. It was, said the Boston Globe in 1909, “an ideal town,” which, in its tradition of “plain living and high thinking,” offered an alternative to an America dominated by the “commercial spirit.” Founded on Puritan rectitude, the town focused on “destiny rather than dollars,” cultivated a heritage of liberty and conscience, and brought forth two American revolutions. The first was the opening battle of the War of Independence, when minutemen confronted British regulars at the North Bridge on April 19, 1775; the second the movement for intellectual independence associated with the Transcendentalist writers and residents Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. “It is a model of what a New England town should be,” observed the Globe. “Concord, one of the oldest towns in the commonwealth, has retained through all the stress and strain of 275 years much of her pristine purity and most of her Puritan ideals.” As the home of Puritans, minutemen, and Transcendentalists, Concord symbolized the New England tradition at its best.

Few places enjoy so enviable an image. But such reputations do not arise spontaneously in a culture. They are consciously crafted by interested parties to shape the present and the future. Concord’s identity in the public mind was the work of several generations, inside and outside the town, and for all its apparent seamlessness, it gathers together strands of thought that were once incompatible. Who invented this pristine, revolutionary Concord, and why?

I. Concord staked its claim to be the birthplace of Independence during the celebration of “America’s jubilee” on April 19, 1825, the fiftieth anniversary of Concord Fight. Concord was then an expansive town of nineteen hundred inhabitants, thriving with crafts and trade in the village and surrounded by farms prospering on demand from rising urban centers in the long boom that accompanied the opening phase of the Industrial Revolution in the Northeast. It also occupied a prominent place on the political landscape; as a shire town, where the county courts convened, it had risen into a leading center of Middlesex County, and its politicians were major players on that stage. Economic and political ambitions, as well as pride in the past, drove the insistence that Concord was the “first site of forcible resistance to British aggression.”

It may seem natural to us that in 1825 the children and grandchildren of minutemen would commemorate the fight at the North Bridge. It was not. Concord had, in fact, done little to mark the occasion since April 19, 1776, when the town minister, the Reverend William Emerson, preached an anniversary sermon in honor of the “memorable Day that . . . marked in plain though crimson Lines the Path of Duty for those to tread, that nobly scorned to wear the british Yoke.” Like his colleague, the Reverend Jonas Clark of Lexington, who also gave a public address that day “to commemorate the murder, blood-shed and commencement of hostilities, between Great-Britain and America” in his town, Emerson meant to shore up patriot morale. He was soon off to serve and die as chaplain to an ill-fated military expedition to Ticonderoga; the annual anniversary sermon ended with him. Still, civic pride remained strong, and townspeople never lost an opportunity to remind others of their indispensable role in the Revolution. Twice–once in 1792 and again in 1813-14–they sought aid from the state legislature to erect a monument to the battle, only to be foiled by alert representatives from Boston, jealous lest Concord gain greater prominence and thereby strengthen its recurrent bid to become the capital of Massachusetts. In 1798, as war with France appeared imminent, a group of fervent Federalists held a public meeting and vowed “in holy remembrance of those who bled” on “the memorable 19th of April” to “defend by our valor, what they won by their blood.” The beleaguered President Adams appreciated Concord’s support, but advised his supporters to drop all that talk about April 19. This was no time to stir up old resentments against British “cruelty”: “If Concord drank the first blood of martyred freemen, Concord should be the first to forget the injury when it is no longer useful to remember it.”

Whatever the reason, the inhabitants made few public displays of local patriotism. Training days for the militia were rarely scheduled for the nineteenth of April, and when the citizens assembled to celebrate American Independence, it was on the Fourth of July. Such commemorations were invariably held in the village, not at the battlefield. Back in 1792, the North Bridge had been torn down and the main road over the Concord River rerouted; the adjoining land fell into the hands of the Reverend Ezra Ripley, Emerson’s successor in the pulpit and the Old Manse, who incorporated it into his back pasture. It was no longer possible to travel to the site of “the shot heard ’round the world.” Then again, with so many veterans of Concord Fight still living in town, trading reminiscences in the taverns and telling tales of military glory to eager young boys, there was no special need to do so.

All that changed with the approach of the jubilee. On April 19, 1824, the two volunteer military companies, the Concord Artillery and the Light Infantry, drilled on the common, enjoyed a public dinner, then marched to the battle site, where their host, the Reverend Ripley, delivered “an instructive address.” Five months later, the aging Marquis de Lafayette came to town, near the start of his year-long procession through the republic as “the nation’s Guest.” That gala occasion certainly burnished local pride; George Washington’s old comrade in arms was delighted to be “at the place where the first resistance was made to British invasion in 1775,” regretting only that he could not personally visit the exact spot. But the affair was also something of a public relations disaster. The official reception was held in a tent on the common, which had room only for town officials, the welcoming committee, a few veterans, and the ladies who served the cake and punch; everybody else had to glimpse the festivities from behind the ropes that cordoned off the tent and were patrolled by soldiers. In their eagerness to see the general, many inhabitants pressed against the barriers, the guards pushed back, and tempers rose. Some people began to complain aloud at the favoritism: “although they were not as well dressed nor as educated in society . . . as those within . . . their fathers had served the country, some had fought with Lafayette in the battles of the Revolution, and they were as grateful for his services.” Luckily, the town escaped a riot. Ten years later, resentment was still simmering as Concord prepared to celebrate its bicentennial. One resident dubbed the birthday party “Another Lafayette Celebration!” and vowed to boycott the event. “Well do I remember the insulting treatment I received when, among others, I attempted to look at Lafayette; we had to stand back then at the point of the bayonet, whilst the great folks sat and drank at our expense.”

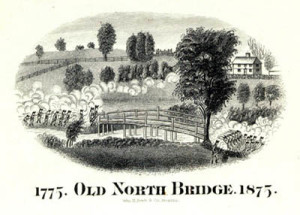

Despite such complaints, Concord’s leaders moved forward with plans for a large-scale commemoration of the April 19 jubilee. At the initiative of ten inhabitants, including the father of Henry David Thoreau, the town meeting voted in March 1825 to hold a public celebration of the “Concord Battle, in which the enemies of freedom were first met and forcibly repulsed by brave Americans.” This was to be more than a local affair. Six months earlier, the newly formed Bunker Hill Monument Association had launched a public campaign to raise money for erecting its proposed memorial to the Charlestown battle that broke British military power in Massachusetts. In a bid to win support from Concord, the association pledged part of its funds to build a smaller monument in the town “where the first conflict was had.” Not surprisingly, Concord seized on the proposal and joined its commemoration to the Bunker Hill scheme. Two events dominated the ceremonies on April 19, 1825: the laying of a cornerstone for the monument in the village center and the delivery of a formal address at the meetinghouse by Edward Everett, the Harvard professor who had parlayed his role as secretary of the Bunker Hill Monument Association into a successful candidacy for the Middlesex County seat in Congress at the recent November 1824 elections. With these decisions, Concord highlighted the agenda of the BHMA, whose conservative leaders, drawn from Boston’s elite, aspired to impose their Federalist vision of society on New England. Commemorating the past was a key instrument of that purpose; through public observation of such landmark events as Forefathers’ Day, when the Pilgrims supposedly stepped onto Plymouth Rock, and of the Concord Fight, the elite hoped to gather a deferential populace behind its leadership, in shared “patriotic feelings” on “sacred ground.”

That agenda certainly suited the leading figures in Concord, such as the lawyer Samuel Hoar, who was designated “president of the day” by the committee of arrangements for the April 19 celebration. Back in 1820-21, Hoar had represented Concord at the state constitutional convention, and he had worked closely with Daniel Webster and other Federalist leaders to preserve those twin pillars of the social order: tax support for ministers and churches and property qualifications for suffrage and office. His Concord colleague at that conclave was the lawyer John Keyes, a Republican who pushed for the expansion of voting rights but had no objections to the establishment of religion. The two men were archrivals, who, within a decade, would end up as fellow travelers in the Whig Party. On April 19, 1825, both were overshadowed by Everett, who, as it happened, had soundly defeated Keyes for his congressional seat. Keyes was reduced to offering a toast at the public dinner following Everett’s address. Hoar, who was inexplicably replaced at the last minute as president of the day, made no mark in the official records.

Everett’s two-hour address to a “crowded audience” enhanced his reputation for eloquence and won him equal standing to Daniel Webster as the leading orator of New England’s “Age of Commemoration.” He surely flattered his listeners, who included veterans of the fight wearing special badges of honor, by lifting events of April 19, 1775, to the plane of universal history. “It was one of those great days, one of those elemental occasions in the world’s affairs, when the people arise, and act for themselves.” In this rehearsal of events, it was not the murderous advance of British troops on Lexington Common or the two-minute skirmish at Concord Bridge that seized Everett’s attention. The longest part of the narrative recounted the rallying of “the indignant yeomanry” in response to the Concord alarm: “unprepared husbandmen, without concert, discipline, or leaders,” drove the “picked men” of the British army back to Boston in defeat. With this theme, Everett deftly got himself out of a sticky situation. In the months leading up to the jubilee, spokesmen for Lexington and Concord had conducted a public feud over which town deserved credit for mounting the first resistance to the British assault and thus for starting the Revolutionary War. Concord mocked the sudden effort by Lexington to turn a “massacre” into a “battle.” Lexington replied by charging Concord, a bigger and richer town, with trying to steal the laurels from “the little village . . . that reared this Spartan band.” This petty quarrel, which bemused outsiders, would occupy the champions of both towns for decades. Everett sidestepped the controversy: when visitors ask where “the first battle of that great and glorious contest was fought,” we can “with honest complacency” direct them “to the plains of Lexington and Concord.” He showered his praise on the yeomanry who poured out from every Middlesex village and farm to vindicate the character of American freemen. Conveniently, those same Middlesex citizens had just elected him to Congress.

If Everett neglected to flatter Concord’s ego sufficiently, the Bunker Hill Monument Association managed to ruffle a good many feathers. Its pledge of financial aid for Concord’s monument came with two strings attached: first, the structure had to be a smaller scale version of the obelisk designed by Solomon Willard to ornament Bunker Hill–a provincial chip off the metropolitan block; second, it had to be located in the village center. Nobody, to my knowledge, objected to the style requirement, but the site provoked disagreement. In principle, there was a good case for the village; the British had, after all, spent more time in the center on their search-and-destroy mission than at the North Bridge. The proposed location would also be good for business, attracting visitors to nearby taverns and shops. These arguments proved persuasive; by an overwhelming margin, 65 to 25, the citizens endorsed the site by the town pump. And so, at the start of the April 19 celebration, the local Corinthian Lodge of Masons laid the cornerstone of the monument with “great solemnity . . . calculated to make a deep impression on the mind.” Beneath that “huge granite block, some four feet cube,” they buried a lead box containing various documents, including newspapers of the day and descriptions of the government of the United States and of Massachusetts, and a plate inscribed with an unambiguous statement of Concord’s priority in the Revolution: “Here on the 19th April 1775, began the war of that Revolution which gave Independence to America.”

Who could complain? Evidently, a fair number of inhabitants remained unreconciled. One morning in the winter of 1825-26 the villagers awakened to discover an unusual formation atop the cornerstone: a pile of tar barrels and boards, twenty feet high, raised in mockery of the site. “This monument is erected here,” explained the inscription, “to commemorate the battle which took place at the North Bridge.” The satirical display didn’t last long. The following night “some of the rowdy element,” aggressively defending village honor, set the sham monument on fire. It was a “great illumination,” one witness recalled years later. Unluckily for the assailants, their action proved self-defeating. The cornerstone was ruined. No shaft ever rose above the base.

Nobody took credit for the mock monument or its destruction. Neither did the wits elaborate on their joke; for them, the absurdity of the village site was self-evident. How could anybody think to place a monument in the center, the very scene of the successful British occupation, rather than at the North Bridge, where the Concord and Acton militiamen had been the first to oppose that aggression? All those polemics on Concord’s behalf had done their work. But something greater was at stake than mere local pride. Time and again, commemorative speakers called attention not just to the armed resistance at the North Bridge but to the shedding of British and American blood. One toast at the celebratory banquet hailed “The town of Concord–Consecrated by the blood of the first martyrs to American liberty.” Another, given by the representative of Lexington, tactfully paid tribute to “The Genius of Liberty,” who “rose from the blood-stained field of Lexington, and waved her celestial banner over the land, the chains of tyranny were broken asunder, the nation was disenthraled.” It was, indeed, to preserve the memory of those sacrifices that Edward Everett dedicated his ceremonial address: “Above all, their blood calls to us from the soil which we tread; it beats in our veins; it cries to us . . . ‘My sons, forget not your fathers.’” In short, through the spilling of blood, the “embattled farmers” consecrated the ground, and only on the site of their martyrdom should a monument be raised. The farmers’ fields, bordering the ruins of the bridge, were sacred space.

II. A decade later, by the mid-1830s, with over two thousand inhabitants, Concord was probably at its political and economic pinnacle. The central village hosted some nine stores, forty shops, four hotels and taverns, four doctors and four lawyers, a variety of county associations, a printing office and a post office. Manufacturing was humming, too, with a growing mill village in the west part of town, along the quick-running Assabet River, and rising producers of carriages and chaises, boots and shoes, bricks, guns, bellows, and pencils. But a good many people were left out of the prosperity. In what was still a farming town, 64 percent of adult males were landless, while the top tenth of taxpayers, some fifty men, controlled nearly half the wealth. Those who failed to obtain a stake in society, native and newcomer alike, quickly moved on. The ties that once joined neighbors together were fraying. On the farms, the old work customs–the huskings, roof-raisings, and apple bees–by which people cooperated to complete essential chores gave way to modern capitalist arrangements. When men needed help, they hired it, and paid the going rate, which no longer included the traditional ration of grog. With a new zeal for temperance, employers abandoned the custom of drinking with workers in what had been a ritual display of camaraderie. There was no point in pretending to common bonds.

With the loosening of familiar obligations came unprecedented opportunities for personal autonomy and voluntary choice. Massachusetts inaugurated a new era of religious pluralism in 1834, ending two centuries of mandatory support for local churches. Even in Concord, a slim majority approved the change, and as soon as it became law, townspeople deserted the two existing churches–the Unitarian flock of the Reverend Ripley and an orthodox Calvinist congregation started in 1826–in droves. The Sabbath no longer brought all ranks and orders together in obligatory devotion to the Word of God. Instead, townspeople gathered in an expanding array of voluntary associations–libraries, lyceums, charitable and missionary groups, Masonic lodges, antislavery and temperance societies, among others–to promote diverse projects for the common good. The privileged classes, particularly the village elite, were remarkably active in these campaigns. But even as they pulled back from customary roles and withdrew into private associations, they continued to exercise public power. Such pretensions were guaranteed to ignite political conflict.

The explosion came in the form of Anti-Masonry, which swept through Concord from 1833 to 1835 with as much intensity as it had in the “burned-over district” of New York state, where the movement got its start. It was propelled by the conviction that Freemasonry, once associated with Revolutionary heroes George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, posed an imminent threat to the republic. Bound together by secret oaths, conducting business behind closed doors, allegedly promoting one another’s interests through command over the levers of power, the Masons epitomized the contradictions of the emerging social order. In the link between private loyalties and public influence, opponents detected “an engine of conspiracy for any evil or selfish purpose.” Concord’s Masons were acutely vulnerable. They had taken a special role in the jubilee celebration. Their members occupied every level of power, from state senator John Keyes to the captain of the Concord Artillery to the editor of the local newspaper, who experienced a sudden change of heart in 1833 and defected to the enemy, converting his press into an organ of Anti-Masonry. The most prominent target was the Reverend Ripley, a Mason of thirty-five years’ standing and Grand Chaplain of the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge of Massachusetts.

In this atmosphere of conflict, the eighty-three-year-old Ripley turned to history as a means of reuniting the distracted town. In 1834, he proposed to donate the land behind the Old Manse for a monument to commemorate “the Great Events at Concord North Bridge on the 19th of April 1775.” Immediately, a few critics arose to denounce the scheme: Why should a monument be located in “the backside of Dr. Ripley’s house?” But the town snapped up the offer, in part because it cost the inhabitants nothing. The land was free; the costs of upkeep were paid by private donors; the fund set up in 1825 financed construction. All the town had to do was authorize a change of venue. By this reliance upon private money to facilitate public ends, Ripley and his allies cleverly removed the issue from democratic give-and-take.

At the same time, the parson’s offer was intended to forge a new basis for civic unity, as he made clear in a lecture to the Concord Lyceum on April 19, 1837. Taking stock of the “agitated and unsettled state of society,” Ripley reminded his listeners that “a well-regulated town or parish” is like “a swarm of bees, clinging together in one body, mutually sustaining and depending upon one another . . . If those in the centre let go their hold, the whole body fails; and if the surrounding multitude fly off, the whole swarm is broken up.” In what is a familiar theme today, the patriarch who had presided over Concord for six decades bewailed the loss of community. Neighbors used to know one another, share mutual interests, respect others’ views. Now, with so little in common, they exaggerated “differences in opinion, on religion and politics” and polarized the community. Ripley’s gift was designed to heal those rifts. It would pull Concord together in common reverence for the Revolution. It would highlight the blessings of Providence. It crystallized a new civic identity. It consecrated a sacred landscape.

As the aging parson was creating a lasting legacy, his step-grandson Ralph Waldo Emerson was on the threshold of the distinguished career as writer and lecturer that won him enduring fame as “the Sage of Concord.” The latest in a long line of New England clergy, Emerson had abandoned the pulpit in 1832 following the death of his first wife, traveled to Europe and Britain on a journey of self-discovery, and returned to write a little manifesto of his new vision, entitled Nature, while enjoying Ezra Ripley’s hospitality in the Old Manse. Like his grandfather, the erstwhile minister was troubled by the changes unsettling New England, especially the rising conflict between social classes and the unabashed pursuit of self-interest he had witnessed in his hometown of Boston. Sadly, he lamented in 1829, that was “a community composed of a thousand different interests, a thousand societies filled with competition in the arts, in trade, in politics, in private life” and united by no “common good.” Emerson’s solution for disharmony would ultimately take him far from Ripley’s social ethic. Rather than rely on elite leaders and established institutions, he discovered in nature the means to reconcile individual and society.

Out of this personal illumination Emerson forged a radical doctrine of self-trust that earned him a growing following among educated young people and angry denunciations from onetime colleagues in the Unitarian clergy. In the eyes of critics, the respectable renegade from the ministry was a dangerous disturber of social order. But that opinion did not hold in Concord. There Emerson was readily admitted into village elite, following his second marriage, to Lydia Jackson in 1835, and the purchase of a handsome house near the town center. In short order, he was elected to membership in the exclusive Social Circle, an organization of the town’s leading men. Emerson was apparently untroubled by charges that the group was a self-styled “aristocracy.” Compared to the great inequalities and social distances of Boston, Concord was a haven of small-town sociability. “Much of the best society I have ever known,” he told a friend in Boston in 1844, “is a club in Concord called the Social Circle, consisting always of twenty-five of our citizens, doctor, lawyer, farmer, trader, miller, mechanic, etc., solidest of men, who yield the solidest of gossip.”

In this benign mood, Emerson delivered the formal address for Concord’s bicentennial in 1835 and composed the hymn for the dedication of the monument at the bridge site on July 4, 1837. Nothing he said would have bothered Edward Everett in the least. The story of Concord, he declared in his ceremonial discourse, is the story of liberty. At their first settlement in the wilderness, the Puritan founders of the town established government and society upon an ideal plan. “The nature of man and his condition in the world, for the first time, . . . controlled the formation of the State.” For all his vaunted nonconformity, Emerson was as attached as his neighbors to the conventional wisdom regarding Concord’s decisive part in the events of April 19: the clash at the North Bridge was “the first organized resistance . . . to British arms.” Turning to the handful of veterans of that memorable day who were sitting in his audience, the thirty-two-year-old orator offered up an encomium that could have come from Webster or Everett: “If ever men in arms had a spotless cause, you had.”

Emerson never swerved from this serene prospect on the local past, which he rendered for posterity in the elegiac lines of the famous “Concord Hymn.” In fact, over the succeeding decades, as he developed into a leading critic of New England society and a powerful advocate of antislavery, he avoided the subject altogether. Having launched his literary career by bewailing the filiopietism of his contemporaries, he fastened his attention on “the signs of the times,” in hopes of discovering the transcendent meaning of passing events. This evasion of history is striking, for in the 1840s and 1850s, at the high tide of the crusade against slavery, Concord was astonishingly attentive to its heritage. Alarmed by the disarray of its records, gathering dust in the possession of the town clerk, Concord spent a remarkable seven hundred dollars to put its archives in order and installed a fireproof safe in its new Town Hall, built in 1852, for their protection. Its leaders, notably, Samuel Hoar, played a leading part in winning passage of a state law in 1851 “for the Better Preservation of Municipal and Other Records.” Doubtless, Emerson observed and approved these initiatives, but they made little impact on his prose. Even when Emerson thundered at the knavery and the cowardice of Massachusetts’s leaders in the face of an aggressive slave power, he seldom contrasted them with the legendary figures of the Revolution. Instead, he derided the patriotic speeches gotten up for “the nineteenth of April” and the Fourth of July as “a great deal of nonsense” belied by New Englanders’ support for the Fugitive Slave Law. There was once a time, he observed in an 1855 “Lecture on Slavery,” when America’s leaders were its “foremost” men: “Washington, Adams, Jefferson, really embodied the ideas of Americans. But now we put obscure persons into the chairs, without character or representative force of any kind.” More often, he urged listeners to take action for themselves: “You must be citadels and warriors, yourselves Declarations of Independence.”

It was left to Thoreau, “the man of Concord” Emerson called him, to quarrel strenuously with his neighbors’ version of the past. Though he is famous for blithe dismissal of his elders, Thoreau was actually remarkably attentive to local history. One of the wittiest sections of Walden is his mock-heroic account of the battle of the ants, whose combatants far outstripped the minutemen in “patriotism and heroism.” “For numbers and for carnage it was an Austerlitz or Dresden. Concord Fight! Two killed on the patriots’ side, and Luther Blanchard wounded! Why here every ant was a Buttrick.” But in the struggle against slavery, Concord’s Revolutionary heritage was no laughing matter. Though many inhabitants, especially women, were quick to enlist in the abolitionist movement– Thoreau’s mother and aunts and Emerson’s wife rallied early to William Lloyd Garrison’s cause–and though prominent politicians, such as Samuel Hoar and his son Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar, played key roles in the founding of Free Soil and Republican Parties, the local elite contained a fair number of entrenched Old Whigs, who put “cotton” over “conscience.” (Rockwood Hoar coined that very notion.) In 1850, for the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Concord Fight, the town staged a great “Union” celebration, at a time of national crisis over slavery. The first choice for speaker was Senator Daniel Webster, who declined, citing his immersion in the desperate effort to find a national “compromise.” That was fortunate for Concord; after March 7, when the great orator endorsed the Fugitive Slave Law, Webster was execrated by many of his one-time worshipers. Emerson pronounced the judgment on Webster: “The fairest American fame ends in the filthy law.” The eventual speaker was Robert Rantoul Jr., an antislavery Democrat who would briefly succeed Webster in the Senate. On April 19, 1850, Rantoul was discreet. Not until the final sentence of his address, in the course of which he celebrated “the site of the old North Bridge” as “the pivot on which the history of the world turns,” did the speaker breathe a hint of the issue that was on everybody’s minds. Charging his listeners to safeguard “the beacon-fire of liberty whose flames our fathers kindled,” Rantoul invoked those in dire need of its “refulgent” light, including “the wanderers in the chill darkness of slavery, [whom] it guides, and cheers, and warms . . . ” In Emerson’s view, this was a paltry performance, noted only for its “wearisomeness” and “painfulness.” Thoreau ignored it altogether.

What Thoreau did not overlook was his neighbors’ reluctance to put their antislavery sentiments into action. In 1854, as the Fugitive Slave Law continued to be enforced in Massachusetts, he derided popular preoccupation with the fate of Kansas and Nebraska and indifference to oppression at home. “The inhabitants of Concord are not prepared to stand by one of their own bridges, but talk only of taking up a position on the highlands beyond the Yellowstone river. Our Buttricks, and Davises, and Hosmers are retreating thither, and I fear that they will have no Lexington Common between them and the enemy.” Rantoul’s “beacon-fire of liberty” was fast dimming out. Fortunately, in Thoreau’s view, it was rekindled by that revolutionary from out of the West, John Brown. In the simple grandeur of Brown, Thoreau found a way to reclaim the New England heritage. The man possessed the indomitable spirit of a Puritan soldier in Cromwell’s army. “He was like the best of those who stood at Concord Bridge once, on Lexington Common and on Bunker Hill, only he was firmer and higher principled than any that I have chanced to hear of as there.” Best of all, educated not at Harvard but “at the great university of the West, where he sedulously pursued the study of Liberty,” Brown devoted his entire self to a noble ideal. In the highest praise he could offer, Thoreau branded his hero “a transcendentalist above all, a man of ideas and principles,–that was what distinguished him. Not yielding to a whim or transient impulse, but carrying out the purpose of a life.”

Thoreau’s forceful rhetoric had an unintended effect. By embodying the New England heritage in a living individual, he meant to inspire others to heroic action. But conflating Puritans, minutemen, and Transcendentalists together could foster complacency. New Englanders might consider themselves the nation’s conscience, even when they merely cultivated lofty thoughts in their gardens. By such literary means, the Concord philosophers were domesticated to their town and region. In 1853, the writer George William Curtis, who had resided in Concord for several years following a brief sojourn at Brook Farm, sketched the town of Emerson and Hawthorne in a volume aimed at literary tourists, entitled Homes of American Authors. Taking his inspiration from their writings, Curtis conjured up Concord from Emerson’s and Hawthorne’s texts. Emerson expressed the spirit of the place. “The imagination of the man who roams the solitary pastures of Concord, or floats, dreaming, down its river, will easily see its landscape upon Emerson’s pages.” Hawthorne evoked its legends in Mosses from an Old Manse. (Thoreau, who had not yet published Walden, received no mention.) In Curtis’s telling, Concord enjoyed a happy life as a writer’s retreat. Untainted by industry and trade, populated by plowmen and poets, associated with a fabulous past and eternal nature, the town belonged to the realm of the pastoral: a place apart from its own time, where an urban visitor might gain respite from the pressures of modern life. In Curtis’s pages, Transcendentalism and tourism merged. A trip to Concord was a spiritual experience.

That new identity took hold, in part because it refracted an undeniable reality. With the coming of the railroad in 1844 and the waning of the village as a vital economic and political center, Concord underwent an alteration from town into suburb. Though it continued to support numerous dairy farms and market gardens geared to demands from Boston, and its textile mill held on till the 1890s, an increasing number of residents began commuting regularly to jobs in the city. Many fewer people came to Concord for business. The regular stages stopped running; teamsters no longer carried country produce to local stores; eventually, the county courts decamped for the industrial city of Lowell. Devoid of its former liveliness, the village struck one short-term resident, the ex-urbanite Harriet Hanson Robinson, as something of a ghost town: “It is a dull place,” Harriet complained. “It is a narrow old place. It is a set old place. It is a snobbish old place . . . It is full of graveyards, and winters are endless. The women never go out, and the streets are full of stagnation.”

In such a placid setting, it is easy to see how Concord, with its rich heritage, attractive landscape, and literary associations, could become a retreat from the wider world. Local inhabitants were soon publishing tourist guides, which proliferated in the wake of Louisa May Alcott’s great success with Little Women and its successors and after Walden became a pilgrims’ Mecca. As early as 1862, a short-lived magazine entitled The Monitor was half-facetiously suggesting that visitors would be better off skipping the annual April 19 ceremonies and spending their time in the woods, where they might run into a local philosopher. “Leave business behind . . . Money, too, for there is nothing here that money will buy. Fashion as well, for it, alone, does not pass current here. Do not despise anyone you may meet in the woods, or up the river on account of their clothing.”

But nature did not displace history, nor did tourism eliminate activism. Little more than a year before that Monitor article, on April 19, 1861, a new generation of young men joined their military companies on the town common to answer Lincoln’s call for troops; six years later on that date, Concord raised its Soldiers’ Monument on the site. The nineteenth of April would continue to accrue meanings over the years, as its message of liberty and community was reinterpreted for new generations. In the Gilded Age, as Anglo-Saxon nativism surged in the face of mass immigration from southern and eastern Europe, it was often an occasion for narrow, ancestral pride. But the minutemen could also inspire a larger vision of freedom. On the very first Patriots’ Day in 1894, Rockwood Hoar, the former attorney general of the United States– who had watched the 1825 celebration as a schoolboy, served as president of the 1850 commemoration, and hosted President Grant at the centennial–spurned the parochialism and prejudice that had come to surround the anniversary. Son of the man who had touched off the feud with Lexington back in 1824, Hoar firmly declared that April 19 belonged to no single town. “It was Massachusetts up in arms that day . . . Whatever was done, Massachusetts did it.” But state pride was no better than town pride, if it expressed a bigoted spirit. In a bold challenge to his own class, Hoar turned to the representatives of the Sons of the American Revolution, who were sitting in the audience, and made a “modest suggestion”: shouldn’t the group end its restriction of membership to blood descendants of Revolutionary War soldiers? “The title to public consideration or leadership in public affairs by reason of descent, is not an American idea.” Surely, “every citizen of the Commonwealth who prefers honor and public service to selfishness and ease, who loves liberty, and will resist tyranny without counting the personal cost, wherever he was born and of whatever lineage . . . should have a right to call himself, and is a son of the American Revolution.”

That notion has enjoyed wide appeal in American culture. Daniel Chester French’s statue of the minuteman at the bridge–the patriotic farmer with a plow under one hand and a musket in the other–served as a popular emblem of the American fighting man in World War II. During the Cold War, “Minutemen” missiles stood guard against Soviet attack. But in recent years, the minuteman has become a favorite of the right wing. Participants in the militia movement of the 1990s seized upon the designation “minutemen” for their extralegal companies of weekend soldiers preparing to fend off an invasive federal government, deemed as dangerous to liberty as ever was the British Empire under George III. By coincidence, it was on April 19, 1993 that federal agents launched their catastrophic raid on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, and confirmed the extremists’ worst fears. Alas, to avenge that attack, Timothy McVeigh chose April 19, 1995 to bomb the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. In his wake, the once “memorable” nineteenth of April now stands not only for the birth of independence but also for the worst episode of domestic terrorism in American history. Attorney General Hoar, who cared passionately about the rule of law, would have been shocked by the new connotations of an event he celebrated as a signal moment in the history of freedom.

To reclaim the day from the paramilitary Right requires more than the patriotic cant of those holiday orations Emerson and Thoreau despised. It calls both for history and for memory, in a continuing interplay between the urge to recapture the past in all its complexity and the impulse to appropriate it for the political and ideological ends of later times. That is a difficult balancing act, but without its discipline, the minutemen are in danger of becoming a symbol for any and every group purporting to be fighting in liberty’s defense. But we can find inspiration in that effort by pausing to reflect on Concord’s ongoing redefinition of itself.

Further Reading: For more on American jubilee celebrations, see Andrew Burstein, America’s Jubilee (New York, 2001). For Thoreau on the battle of the ants, see Walter Harding, The Days of Henry Thoreau: A Biography, rev. ed. (New York, 1982), 66; Henry D. Thoreau, Walden, ed. J. Lyndon Shanley (Princeton, 1971), 9, 230; John McWilliams, “Lexington, Concord, and the ‘Hinge of the Future,’” American Literary History 5 (Spring 1993): 1-29. See also Robert A. Gross, The Minutemen and Their World (New York, 1976) and “The Celestial Village: Transcendentalism and Tourism in Concord,” in Charles Capper and Conrad Edick Wright, eds., Transient and Permanent: The Transcendentalist Movement and Its Contexts (Boston, 1999); and Harlow W. Sheidley, Sectional Nationalism: Massachusetts Conservative Leaders and the Transformation of America, 1815-1836 (Boston, 1998).

This article originally appeared in issue 4.1 (October, 2003).

Robert A. Gross is James L. and Shirley A. Draper Professor of Early American History at the University of Connecticut in Storrs. He is the author of The Minutemen and Their World, 25th anniversary ed. (New York, 2001) and The Transcendentalists and Their World (forthcoming). In 2002-03 he was Mellon Distinguished Scholar in Residence at the American Antiquarian Society, where this essay was first presented.