Perhaps it’s only fitting that a history of the Dead Letter Office requires an exhumation: or more precisely, that to see the records of the nineteenth-century Division of Dead Letters in the National Archives, you must deliberately misaddress your call slip. So I discovered when I set out to write a history of the nineteenth-century Division of Dead Letters.

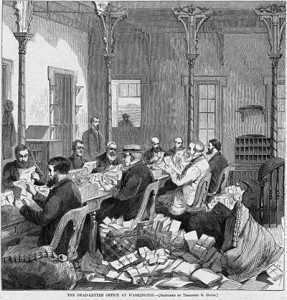

The Dead Letter Office in Washington was the obscure section of the Post Office charged with processing undeliverable mail. Until World War I, all undeliverable letters were processed through the central office in Washington. Only the clerks of the Division of Dead Letters were authorized to open them, and only for the purposes of salvaging valuable enclosures and attempting to locate their proper recipients (fig. 1). By law, unclaimed letters were burned, pulped, or otherwise destroyed, and with them all evidence of the clerks’ labor, the failed communications, and the federal bureaucracy that sheltered both. Indeed, according to the finding aids for the National Archives and Records Administration, all that remains of the Dead Letter Office’s operations is a single box of administrative documents: “Miscellaneous records, 1897-1930.”

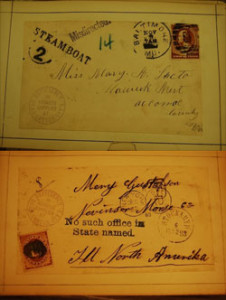

So I was surprised when, after three days of filling out a call slip for the same box with increasing imprecision, a different box rolled into the reading room, this one labeled “1830-1876.” I was even more surprised to find among these records four unsealed letters from 1889, neither burned nor pulped, but preserved in their original envelopes and bound with string. These misfiled and undocumented pieces were the only letters in an otherwise administrative archive.

Here was a riddle: in a non-existent box were four letters that should have been destroyed.

Their presence was evidence that the information system had failed at every point: in the aborted transit of the letters, their survival in the archives of an office committed to their destruction, and the absence of those archives from the public record meant to guarantee their preservation. Why were the letters saved and the archives lost? What would I learn if I followed the American system of communications to its end—and then opened the grave? In the end the letters revealed a forgotten episode of federal surveillance and the incipient arguments it provoked on behalf of civil liberties. The episode would haunt me as I labored to understand the political economy of information in a post-9/11 world.

If we’ve long since forgotten the functions of the Dead Letter Office, nineteenth-century Americans had not. The willy-nilly growth of the nation that had made its postal system a logistical marvel also required the establishment of a hub to process misdirected letters. When letters proved undeliverable, they were sent to the central post office in Washington. There, according to one journalist’s report in 1852, clerks labored in “tomb-like” quarters, sorting misdirected love tokens or messages from dead soldiers that languished for months before being “consigned to the paper-mill.” In the early nineteenth century, unclaimed letters were carted off to Monument Square and burned. Reportedly “several hours elapsed before the conflagration was complete.” As the quantity of letters increased, the Dead Letter Office began selling undeliverable mail to local paper mills to be mulched. In 1855, local newspapers charged that the mills harbored a surfeit of misplaced letters, carelessly discarded by postal clerks. These tales circulated so widely through the national press that the Postmaster General ordered an investigation and a visit to the mills in question.

During this time, the Dead Letter Office remained a small-scale operation, dedicated to preserving the inviolability of letters against theft and intrusion. In the 1830s and 1840s, Superintendent of Dead Letters M.J. Simpson answered letters of inquiry by hand, assuring patrons of the Post Office that “no letter having an enclosure of any kind . . . escapes the attention of the persons employed to open [them] and none are permitted to touch or open letters, but those sworn men, who are of tried character, and constantly employed on that duty.” The contents of parcels, not subject to the protections of first-class letters, were put on display in the Minor Letters Room of the Dead Letter Office, where they became objects of curiosity for tourists before being auctioned off en masse (figs. 2, 3).

In the decades after the Civil War, railway mail dramatically increased the volume of mail in circulation. Waves of immigration generated corresponding waves of undeliverable mail, with illegible and incomplete addresses marking the lot of transient people from east to west. An even greater glut of printed matter further strained the operations of the Dead Letter Office. Pamphlets, periodicals, and circulars crowded local post offices, offering miracle cures, counterfeit money, fake prizes, and pornography. The mails had become a vast channel for unsolicited information and global traffic in consumer goods.

The single Dead Letter Office in Washington was becoming an anachronism. By 1879, the office was processing 216.72 tons of mail a year at a cost of $16,088.76; yet in spite of this volume, as late as 1906 two lone clerks in Washington were employed in the Sisyphean practice of “blind reading,” meditating over inscrutable addresses in hopes of conveying their missives into the right hands. With the opening of new branch offices in 1915 came the end of the central Dead Letter Office in Washington (fig. 4).

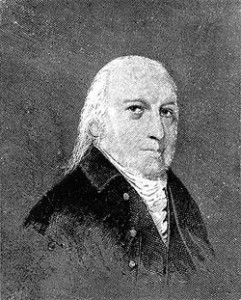

More striking than this unremarkable story of Progressive efficiency was the story of liberty and surveillance it obscured, the first hints of which I found in the journals of the Continental Congress. In light of encomia to the inviolability of the mails, one might not expect that the first Inspector of Dead Letters was appointed as an act of war. On October 17, 1777, the Continental Congress authorized postmaster of New York City and Surveyor General Ebenezer Hazard “to examine all dead letters, at the expiration each quarter, to communicate to Congress such as contain inimical schemes or intelligence.” In the wake of the war, Postmaster General Hazard suggested to Congress that the inspector’s authority to report inimical schemes remain (fig. 5). In 1782 Congress renewed the authority, but without the language regarding intelligence. (A long passage stricken from the draft, preserved in the manuscripts division of the Library of Congress, proposed convicting as spies “enemies” or “subjects” of the United States who robbed post-riders.) Only the mandate to preserve “money, loan office certificates, lottery tickets, notes of hand, and other valuable papers” remained in the 1782 act. For the moment, treason took a backseat to commerce.

This respite proved short-lived. The Postal Act of 1792 forbade carriers to “unlawfully detain, delay, or open, any letter, packet, bag or mail of letters entrusted to them.” But the alien and sedition crisis of 1798-1800 rendered these protections temporarily inert. While later commentators frequently extolled the inviolability of the mails, the mandate for surveillance was only shallowly submerged. In the 1830s the Postmaster General banned incendiary abolitionist tracts from the mails. During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln suspended habeas corpus and opened all mail to inspection, making the Dead Letter Office a locus of intelligence once more.

The four letters that I found in the archives of the Dead Letter Office were all sent within several months of each other in 1889, by the “Merchants’ Union For Collecting and Reporting Delinquent Debtors.” None bore a return address. The letters survive in their original envelopes, unsealed and bound with correspondence from Chief Post Office Inspector Estes G. Rathbone. Rathbone declared the letters unmailable and requested that they be opened by the clerks of the Dead Letter Office, then returned to his office for inspection. Rathbone deemed the letters unmailable not because of malformed addresses, but because he suspected them of being instruments of fraud. Perpetrating a defamatory scheme common in the later nineteenth century, the senders sought to use embarrassing letters to shame recipients into clearing debts that they did not actually owe.

As Chief Post Office Inspector, Rathbone supervised a band of cops charged with policing the mails, including Anthony Comstock, whose agitations had contributed to the legal prohibition on obscene matter in the mails. In response to the surge of junk mail in the 1860s, legislators had designated new classes of mail (third and fourth) and criminalized mail fraud, lotteries, and obscenity as a single category of unmailable material. Zealots like Comstock converted these regulations into a new taxonomy of morality represented by “the sanctity of the mails.” (The results of their investigations survive in the Fraud Order Case Files of the Post Office Records.)

These inspectors faced frustratingly strict limits on their abilities to detect fraud and obscenity. In spite of Comstock’s zeal, the 1872 act bearing his name had no provision for enforcement of its anti-obscenity provisions, relying instead on the existing postal laws. These statutes in turn forbade postmasters to detain or open sealed mail. Inspector Rathbone knew that having suspect letters opened was the most expeditious way to ascertain the identity of senders. But his inspectors were not authorized to open sealed letters. Only the clerks of the Dead Letter Office were so empowered.

While Rathbone evidently gave little thought to treating the clerks as instruments of his investigation, the leadership of the Dead Letter Office had other ideas. Acting Superintendent of Dead Letters W.G. Perry refused Rathbone’s dirty work, forwarding the matter for legal review by the Assistant Attorney General for the Post Office. From the tone of his letter, one gathers that Perry had seen more than his share of impetuous postal inspectors: “It has always been understood in this Office,” he wrote, “that the right to open sealed matter reaching the Dead Letter Office is only exercised for the purpose of obtaining information to restore it to the proper owner, except with the class of matter mentioned in Section 433 P.L. & R.”

Perry’s exception was a curious one. Section 433 contained the regulations for disposing of obscene material, specifying that it be immediately destroyed unless its sender could be identified, in which case it would be held for inspection. This procedure was the result of compromise. In 1865 the Senate and House had disagreed on whether postmasters had authority to open obscene letters with unpaid postage. They agreed that such mail should be sent unopened to the Dead Letter Office. What happened next was anybody’s guess.

While formally upholding the doctrine of the inviolable seal, legislators had effectively transferred powers of investigation from the postal inspectors to the clerks of the Dead Letter Office. In this respect, the clerks in the Dead Letter Office quietly assumed their original function of surveillance.

Until Perry intervened.

When Rathbone and his inspectors intruded upon the operations of the Dead Letter Office, their public law justifications for surveillance met republican defenses of inviolable letters, intensifying the arguments for both. Assistant Attorney General James Noble Tyner sided with Perry in this case, indicating that to open the letters on Inspector Rathbone’s behalf “would be equivalent to violating the sanctity of the mails, a prohibition of which runs all though the statutes.” Ironically, Perry’s insistence on the “sanctity of the seal” recalled moral language that Anthony Comstock had popularized in his effort to purge the mails of obscenity. Tyner’s opinions mingled this moral vocabulary with that of constitutional law, invoking Fourth Amendment rights to safeguard a person’s papers from search and seizure.

Backed by Tyner’s opinions, Perry returned the suspect letters to Inspector Rathbone, indicating rather gloatingly that his Office had “no lawful authority to open sealed matter sent to it by post-office inspectors, or others [for the] purposes of investigation or prosecution.”

As dead mail, the four letters from the Merchants’ Union For Collecting and Reporting Delinquent Debtors should have been destroyed. But the letters were not dead after all. Postal Inspector J.M Arrington had dispatched them to local postmasters with instructions that they be delivered and then returned to his office: “You can explain to the addressee that the Department wants to know who mailed this letter,” he instructed. Since the proper recipients had opened the letters, technically the letters were no more dead than they were unmailable. Presumably only their delivery and return allow them to be rerouted to the administrative archive of the Dead Letter Office. There they survive, unsealed, despite Perry’s insistence that the Dead Letter Office play no part in aiding investigations. Perhaps Rathbone forwarded them as proof of the senders’ criminality, or as a concession to Perry’s authority. We don’t know.

This obscure skirmish over the statutes for processing unmailable matter represents a neglected chapter in the ongoing conflict between public law justifications for control of communications and its civil libertarian opposition. Contrary to many accounts of American civil liberties, the federal apparatus of surveillance was not simply the innovation of a late-blooming state in World War I, but also a tool used by nineteenth-century reformers, legislators, and administrators attempting to regulate reckless commerce. Federal surveillance of U.S. civilians through the mails has a longer history than is often thought. And although the operations of the Dead Letter Office have become obscure, a global traffic in counterfeit, prohibited, and undeliverable matter continues.

One scholar speculates that Herman Melville read an 1852 Albany Register article entitled “Dead Letters by a Resurrectionist” before imagining the trials of his protagonist, Bartleby the Scrivener, in the Post Office’s “melancholy vaults.” Melville fans will remember that the tale ends with the forlorn discovery that the reluctant clerk had been employed by the Dead Letter Office in Washington before he began work as a copyist at the narrator’s law firm on Wall Street. Many declare Bartleby the hero of the story bearing his name because of his repeated insistence on behalf of workers everywhere that he “would prefer not to”—his refusal to shoulder the burdens of modern life. But it’s the lawyer and narrator, not Bartleby, who struggles with the failures of personal accountability in the world he’s inherited. In this respect he shares the lot of the mid-level bureaucrats assessing the merits of unrestricted commerce versus public security, or the historians trying to do them justice.

That was my story. I conducted this research in the wake of September 2001, which hastened my transition from Wall Street to graduate school. After producing a series of perplexed histories on management accounting and clerical labor, I found myself pledging to produce a history of the Dead Letter Office using the surviving records in the National Archives. Knowing that only one box remained in the archive, I purposely chose what I thought was a dead end. (I figured it would leave me more time to stroll in the park with my dog, Bartleby, a vagrant who appeared—like Melville’s scrivener—on the threshold of my apartment one morning in the summer of 2001.)

If my foray into the archives was more existential than political, however, I proved unable to lose sight of the fact that the democracy I’d been asked to study was also becoming a national security state. On the early train from Penn Station to Washington, I was haunted by an op-ed about the Patriot Act, Capps 2 (Computer Assisted Passenger Pre-Screening System), and the Multistate Antiterrorism Information Exchange (Matrix), set to assemble vast dossiers of personal data about U.S. citizens. Passing the inscription at the entrance of the National Archives, which reads, “ETERNAL VIGILANCE IS THE PRICE OF LIBERTY,” I found the archives transformed by a new approach to security (fig. 6). Even the records of the pneumatic tubes service of the Post Office, through which—pfft—just like that, belle époque missives once circulated beneath the streets of New York, had been classified in the wake of September 11, evidently subject to darker fantasies than mere months before.

Contrary to the myth of the unassailable privacy of the mails, I found that the “sanctity of the seal” had all sorts of loopholes exploited in times of war and peace. And civil libertarian arguments grounded in the First and Fourth amendments were not so much the nation’s founding precepts as nineteenth-century innovations. Exponents of American democracy praised the mails for the free circulation of information they represented. But the mails also provided instruments of moral classification and sites of surveillance in a new, national marketplace of consumer goods. The effort to restrict unregulated commerce and purge the mails of junk exposed contradictions between the ideology and practice of personal security and the freedom of expression. Perhaps there is no such thing as an unremarkable story of progressive efficiency.

Further Reading:

Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street, by Herman Melville, inspired my expedition into the archives of the Dead Letter Office. Taryn Simon’s “Contraband,” a series of 1,075 photographs of confiscated material drawn from the U.S. Postal Service International Mail Facility at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York furthered my interest, as did a middle-of-the-night field trip to the Curseen-Morris Mail Processing and Distribution Center in Washington, D.C., at the annual conference of the Society for the History of Technology in 2007.

David Henkin gives passing attention to the Dead Letter Office in City Reading: Written Words and Public Spaces in Antebellum New York (New York, 1999), as does Richard R. John in Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (Cambridge, 1995). Richard R. John has argued elsewhere that Bartleby’s removal from the Dead Letter Office was a critique of partisanship in clerkship assignments: Richard R. John, “The Lost World of Bartleby, the Ex-Officeholder: Variations on a Venerable Literary Form,” New England Quarterly 70:631 (1997). Dorothy Ganfield Fowler’s Unmailable: Congress and the Post Office (Athens, 1977) and Wayne E. Fuller’s Morality and the Mail in Nineteenth-Century America (Urbana, Ill., 2003) document debates over postal censorship during the nineteenth century.

Record Group 28, The Records of The Post Office Department, 1773-1973, harbors all of the archival collections mentioned in this essay, including the Records of the Division of Dead Letters and the Fraud Order Case Files. http://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/028.html#28.3.7. RG 28 is housed in the National Archives building in downtown Washington, D.C. Paging boxes in the Post Office Records involves several steps. The numerical classification of the online finding aid does not correspond to the on-site index, and due to relocations of postal records, the on-site index does not correspond to the physical location of the boxes in storage. Researchers cross-reference the numbers in the finding aid to those in the on-site index. Archivists cross-reference the numbers in the on-site index to the location in the vault. The tag on the box for Record Group 28.3.7, Miscellaneous Records, 1830-1876, which should indicate the physical location in storage, is RG 28, E. 101, No. 27462, Stack Area 7E4, Row 13, Compartment 5, Shelf 2. It lacks numerical classification or listing in the finding aid.

This article originally appeared in issue 12.2 (January, 2012).