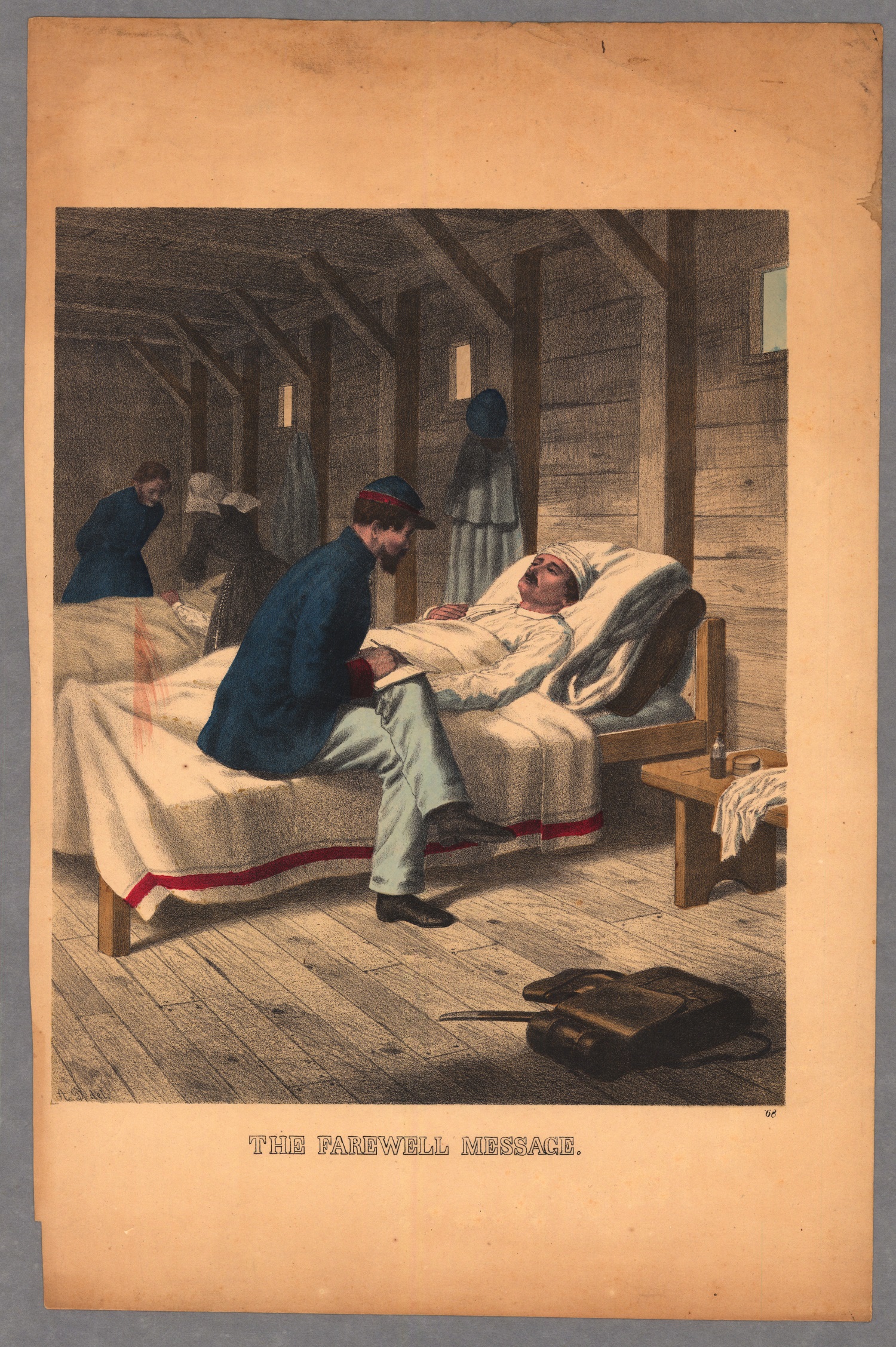

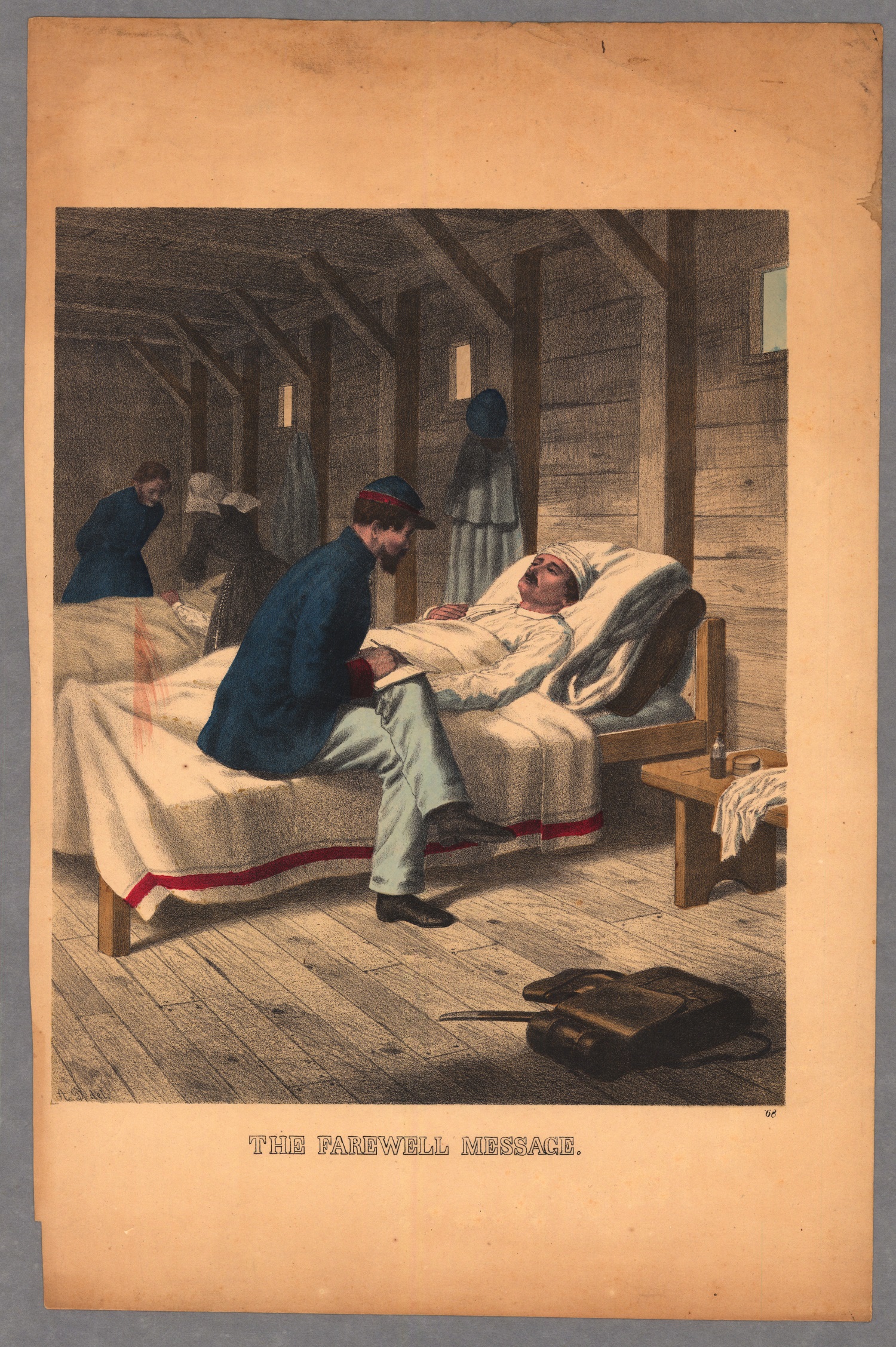

8. “The Farewell Message,” Albert Dubois, hand-colored lithograph, image and text 30 x 23 cm., on sheet 41 x 27 cm. (Fall River, Mass., between 1862 and 1865). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.As Whitman indicates, writing letters by the bedside of the injured and dying became one of the most important kinds of attention a hospital visitor could provide. The need took different forms. Perhaps the soldier had not written to family or friends for some time and could not write now due to injury. There were soldiers who were not literate and who needed a scribe to write on their behalf. As figure 8 illustrates, in the most severe cases, letters represented a final opportunity to say goodbye. It is worth noting that the letter writer in figure 8 is a male Union soldier, thus revising the more common gender dynamic we find in Winslow Homer’s “The Letter for Home.” Thus, Dubois’s image frames the scene of vicarious letter writing less as an instance of domestic surrogacy and more as an allegory of national futurity—the precarious form of the dying soldier’s last words finding through Union fraternity the promise of remaining part of that legacy after he is gone.