Imagining Aaron Burr and Haiti in Leonora Sansay’s Secret History

Strangely, former defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld and Slovenian intellectual Slavoj Žižek can help contemporary readers understand the significance of Leonora Sansay’s fascinating and only recently rediscovered novel of Caribbean intrigue, Secret History; or The Horrors of St. Domingo (1808). Defending the Iraq War, Rumsfeld classified the threats posed by Iraq’s weapons: 1) known knowns, or what we know that we know; 2) known unknowns, or what we know that we don’t yet know; and 3) unknown unknowns, or what we don’t even know that we don’t yet know. According to Rumsfeld, these unknown unknowns were the gravest threat, the unanticipated weapons of mass destruction secretly in manufacture or ready for deployment. Žižek responded to this “amateur philosophising” in the Guardian. He cleverly noted that Rumsfeld left out a fourth category: “the ‘unknown knowns,’ things we don’t know that we know,” or, “the Freudian unconscious.” Although Rumsfeld believed that the unknown unknowns were most disturbing, “the Abu Ghraib scandal shows where the main dangers actually are in the ‘unknown knowns,’ the disavowed beliefs, suppositions and obscene practices we pretend not to know about, even though they form the background of our public values.”

This structure of known/unknown is oddly germane to the development of early republican imaginative prose and especially to Sansay’s peculiar novel. Secret History exposes the unknown known of early republican culture: the nation’s repressed struggle with slavery and the universalist principles embraced in its foundational documents. Turning to fiction, Sansay capitalized on the pioneers of the early American novel but also leveraged the popular appetite for partisan exposé, the indelicate literature of hagiography and partisan penchant for character assassination. Though obscure in its own time and as of yet in ours, too, her synthesis of fiction and biography ought to be recognized as a significant development in American fiction, one that influenced the mock-historical imagination of Washington Irving, the broad historical canvas of James Fenimore Cooper, and the revisionist novels of Gore Vidal. Secret History is a self-consciously diagnostic, imaginative exploration of trends in American letters and their relationship to broader social and political contexts. It’s a great read, but it’s also a tremendously rich experiment in stretching the potential of fiction in the early nineteenth century.

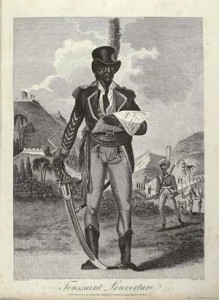

Details about Sansay’s life are sparse. Here’s a summary of what we know: after a many-years’-long relationship with future vice president Aaron Burr, Sansay married a refugee planter from Saint Domingue. Louis Sansay had left his plantation behind at the apex of the slave revolt that would ultimately result in the founding of Haiti in 1804. The Haitian Revolution has so many twists and turns that no satisfactory account can be rendered here, but it should suffice to note that in 1802 the French military reinvaded its break-away colony, seeking to reinstitute slavery and overthrow the revolution’s ambitious leader, Toussaint L’Ouverture. L’Ouverture, a former slave, had promulgated a constitution in 1801 and effectively declared independence. He named himself general in chief for life, established a state religion, and warranted trade relations with the United States, arguably a counterrevolutionary, anti-Jacobin agenda. The constitution turned Toussaint into an object of intense fascination and critical scrutiny in the States; the document was almost immediately translated and widely circulated in the American press in the fall of 1801.

The French invasion abruptly curtailed Toussaint’s rule. In 1802, he was captured, imprisoned, and transported to France, where he would die. Some were extremely gratified by this turn of events. If the chronology of Secret History is to be believed, Louis Sansay and his twenty-nine-year-old wife Leonora arrived back in Saint Domingue on the very date that the defeated Toussaint was embarked for France. Hoping to reclaim his plantation, Louis banked on the triumph of French colonial rule. Leonora accompanied him reluctantly. A letter from Louis Sansay to Burr requests aid to convince Leonora to return to New York; she had apparently run off for Burr’s protection in Washington. Louis feared his wife was having an affair, but it does not appear that Burr was the suspected adulterer. For his part, Burr apparently coaxed Leonora to rejoin her husband. In the end, Louis Sansay was disappointed; France retained control over the island for less than two years before Haiti successfully declared its independence.

The plot of Secret History closely corresponds to this historical record. In it, St. Louis and his beautiful wife Clara arrive in Saint Domingue in 1802, a strained marital relationship is revealed, and finally, as history indicates, once the liberated slaves defeat the expedition sent to re-enslave them, flight to refugee asylums elsewhere in the Caribbean ensues. Leonora’s reasons for returning, alone, to Pennsylvania in 1804 are suggested by the novel’s conclusion, where Clara is subjected to marital abuse, has aqua fortis, an acidic, thrown in her face, and is raped by her husband. Clara’s flight from revolutionary Saint Domingue is thus doubled in her flight from the abusive St. Louis. Eventually, she reconnects with her sister, returns to the United States and also, presumably, to Burr. Clara’s transformation—from victim to liberated, island-hopping, ethnographer of the Caribbean—drives the second half of the novel. It is a story of a woman in flight from both domestic and socio-political strife who finds resources of hope in independence and a series of female-bonding and class-blurring experiences. And as for Sansay? We know that Sansay rendezvoused with Burr and participated in his alleged conspiracy to colonize the western territories; she shows up in court records as a letter carrier for Burr and his associates. But with Burr’s acquittal and subsequent exile to Europe, Sansay turned to fiction, publishing Secret History and Laura almost before the dust of the spectacular trial had settled.

So what makes this novel fit the bill for a starring role in early nineteenth-century American letters? Neither the fascinating details of Sansay’s life nor the plot of her eminently readable novel makes Secret History into much more than a recovered work of women’s writing or an interesting novelization of trans-Caribbean travel amid the tumult of slave insurrection. Rather, it is Sansay’s literary insight that most intrigues. And here, I return to amplify my initial assertion: Leonora Sansay’s Secret History illuminates the early republic’s “unknown known”—its political unconscious—with incredible precision. It makes manifest the young republic’s dominant but repressed problem: a republic founded on liberty that held a vast population in bondage.

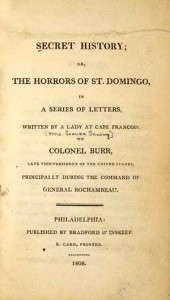

Sansay’s title alone is a rich object of inquiry and deserves to be presented whole: Secret History; or the Horrors of St. Domingo, in a Series of Letters Written By A Lady At Cape Francois To Colonel Burr, Late Vice-President Of The United States, Principally During The Command Of General Rochambeau. What can we learn here? For one, there is no admission that the book is a work of fiction. Although it was long considered a historical work, Sansay herself described “the Story of Clara” as a romance in a letter to Burr.

The title moreover shows how Sansay positioned her work in a publishing environment dominated by novels from Europe and the domestic obsession with partisan disputes fought out through contrary biographical sketches of the Founding Fathers. Mason Locke Weems had published his first edition of The Life of Washington in 1800. Franklin’s works were being made available for the first time, and interest in the second generation political celebrities, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, was stoked through a thoroughly partisan press war. If Secret History gestures to Haiti as the latent but yet unexcavated core of early republican culture, Sansay’s reference to Colonel Burr in her title posits that this oddly enigmatic and politically ambivalent figure offered an occasion for making such a claim. Burr, who personified an underlying disorder, disrupted the cults of personality nourished by the partisans of the 1800s in a manner comparable to the way the Haitian Revolution disturbed the self-absorbed fancies of the American political imagination.

As with the permutations of known and unknown, Sansay’s title gestures at four strands of early republican writing circa 1808 and, in combining these, asserts a common, fundamental thread. The known known corresponds to the rationalist strain of late eighteenth-century fiction, exemplified by Charles Brockden Brown and, in England, the political fiction of William Godwin, especially Caleb Williams. These novelists adapted a gothic aura of mystery and supernaturalism to show the costs of not acting on what ought to have been known about the material world. In Secret History, this corresponds to the manifest content of the secret history to be revealed. The known unknown aptly describes the thinly veiled romans à clef (fictional representations of real events and real people with the names altered) such as William Hill Brown’s The Power of Sympathy and Hannah Foster’s The Coquette, both of which took actual New England sex scandals as bases for their plots. Here, rumor circulates and feeds speculation about the unknown motivations of private individuals whose private actions have attracted intense public interest. These novels manifest what is supposedly known about what remains, in fact, unknown, the moral coding of private misfortune, often through epistolary correspondence made visible for public consumption. Sansay, too, adopts the epistolary form and teases her readers with a tale of seduction, marital violence, and flight. Sansay’s use of Saint Domingue and its revolutionary chaos for her novel’s setting denotes the unknown unknown, the undisclosed intentions of Toussaint, the secret plots of southern slaves, the widespread fear of insurrection, and the lurking fear that discussions of potential insurgency would somehow inspire real insurgency. And finally, the unknown known is brought to the surface through Sansay’s enigmatic reference to Burr, that “Forgotten Founder,” to quote Nancy Isenberg. As with the revolution in Saint Domingue, which revealed strange affinities once placed in service of partisan struggle, Burr disrupted the symbolic coding of the founders. Here we find Sansay’s stunning insight: Haiti and Burr, placed literally on the same page, reveal the partisan frenzy of character assassination and hagiography for a shell game, one that displaced slavery from public consciousness.

There is a notable dead period in the production of domestic fiction after the turn of the nineteenth century. Charles Brockden Brown abandoned writing novels, while Tabitha Tenney, Hannah Foster, and Susanna Rowson turned to more explicit but narrowly pedagogical projects—conduct books for young women. If domestically produced fiction went into hiatus in this first decade, it was in part replaced by the production of partisan biographical sketches of political celebrities.

“It has become customary of late with the federal or tory editors to reprobate the revolution which gave freedom and independence to this country,” wrote Democratic-Republican editor William Duane in “TORYISM called FEDERALISM.” These very same editors, he continued, noting a paradox, “in the same papers eulogize Washington as the greatest and best of men.” The symbolic elevation of Washington had intensified after his death in 1799, and Duane was correct to suspect a partisan motivation. Eulogies and hagiographic character studies were written in spades. Here, Mason Locke Weems’s Life of Washington may be the fullest expression of Federalist nostalgia. In Weems, Democratic-Republicans had a worthy adversary, who crafted a counterrevolutionary but almost saintly portrait of Washington that made Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party appear to be a coven of atheists, radicals, and traitors. Infamous for creating the myth of Washington and the cherry tree, Weems’s key theme was that Washington was a deeply religious man and that those who aimed to lead after his death, but failed to live up to the standards he had set, fell short because they lacked religious faith. Washington the rebel was displaced by Washington the saint of a lost golden age of virtue and stability. As with Weems’s Life, the canonization of Washington often accompanied harsh criticism of the current administration. An early occasion for criticism was Jefferson’s decision to invite Thomas Paine to return from France. Paine’s efforts on behalf of American independence had been eclipsed once he wrote The Age of Reason, within which Federalists divined Paine’s atheism, and after he had had the temerity to publicly criticize Washington in a widely reprinted letter. Jefferson’s patronage left the third president open to charges of a too enthusiastic Francophilia or worse, Jacobinism. Unlike Washington, whose virtues were martial, pragmatic, and confident, Jefferson’s fawning over revolutionary France made him sycophantic, overly philosophical, and weak. His “hand is well enough qualified for the nice adjustment of quadrants and telescopes, but far too feeble and unsteady for managing the helm of government,” wrote Charles Brockden Brown in an anonymously published pamphlet in 1803.

Republicans also played the character assassination game. We’ve already seen how William Duane used the Aurora to ridicule Federalist Tories. The publication in 1802 of John Wood’s History of the Administration of John Adams reached new heights of sarcasm. In his History, Wood, a hack journalist and faithful Jeffersonian, drew favorable character sketches of Jefferson and Burr while pillorying former president Adams and other Federalist luminaries. Fearful that the character sketches were so scurrilous as to harm Republican credibility, Burr bought up all the remaining copies. Not only had the damage already been done, but Burr’s move only spurred the next round of recriminations. Not long after, James Cheatham, one of Jefferson’s harshest critics, published A Narrative of the Suppression by Colonel Burr of the History of the Administration of John Adams, which sought to expose Burr for double-dealing, a threat to both Republicans and Federalists alike. Burrites responded with their own publications in defense of Burr, An Examination of the Various Charges Exhibited Against Aaron Burr, Esq. being but one example .

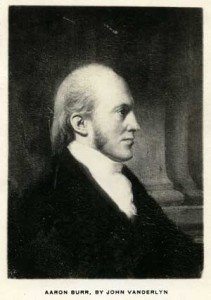

Burr had Federalist supporters but also had Hamilton as his vociferous nemesis; he was embraced but later spurned by Jeffersonians after the election of 1800; he was targeted as well by New York’s Republican dynasty, the so-called Clintonian Faction; and following Burr’s duel with Alexander Hamilton, he became a figure of desire and disgust for both parties. This was the Aaron Burr presciently identified in Sansay’s title, that odd spectre who appears in the epistolary novel only as the silent recipient of letters.

What about Burr made him essential to Sansay’s narrative design? In 1808, he transfixed the public imagination. Not only had he, while the sitting vice president, killed Alexander Hamilton, but he had also recently been acquitted of treason at a wildly engrossing trial in Virginia where spectacular criminal allegations were leveled and an all-star cast of cultural celebrities made significant appearances. Within the partisan tally of legitimate and illegitimate founders, Burr played an indefinite but clearly disruptive role. He had long been associated with sexual deviance and wholly self-interested political machinations. Though a Republican vice president, Burr soon became a favorite son of disempowered Federalists who saw in this grandson of Jonathan Edwards—fine New England stock—a potential turncoat ally. Object of both attraction and repulsion from both nominal friends and nominal enemies, Burr might have been identified with the same symbolic attachments generated by Toussaint L’Ouverture had his contemporaries been willing, as Sansay seems to have been, to see the relationship between Saint Domingue and the biographical obsession with the nation’s founders.

Charles Brockden Brown may have been first to present Toussaint L’Ouverture using a language similar to that usually reserved for celebrations of Washington’s legacy. Criticizing Jeffersonian America in yet another anonymous pamphlet of 1803, Brown assumed the voice of a French counselor of state to argue that Americans had become weak, sullied by self-interested compulsions for personal gain. Aloof to such declension, the intellectual Jefferson was effete, dilatory, and overly bookish—completely ineffective. Toussaint, by contrast, had crafted a ragtag militia of liberated slaves into a disciplined military corps now on the verge of defeating Napoleon’s storied forces. It sounds a lot like Washington at Valley Forge! Jefferson, who never carried arms in the American Revolution, was weak and cowardly; Toussaint was strong, a leader of men, determinate, and in later accounts, a committed Christian as well—all qualities that had animated the recent sketches of Washington. Soon, James Callendar began circulating rumors of Jefferson’s affair with his slave Sally Hemings, a further indication of Republican hypocrisy and moral decline. Toussaint was the publicly esteemed black general; Sally Hemings, by contrast, exposed the scandalous secret life of the slaveholder. The black general of Saint Domingue was preferable to the “Negro president,” so-called not for the Hemings affair but for relying on the electoral advantage given southern states in the constitution’s three-fifths clause. Toussaint fought the France of Federalist ire, while Jefferson co-opted the shameful bonus of the slave population to win power and entrust American policy to the dictates of French puppet masters.

This admiration for Toussaint became a standard Federalist posture. The party of Washington and Adams admired Toussaint for reestablishing order, privileging internal economic stability, strengthening mercantile trade agreements with the United States, reinstating a state religion, and sticking it to revolutionary France and Napoleon. Evidence of this is peppered throughout the Federalist press in 1801, not long after Jefferson’s inauguration. One example was a widely reprinted article entitled “Character of the Celebrated Black General, Toussaint L’ouverture,” a short text that described the “extraordinary man” in terms of his intelligence, achievements, gratitude, and humanity but above all his pragmatism.

Almost as soon as their own standard bearers had lost the reins of government and their heroic patriarch had died, Federalists stumbled upon an ideal replacement in Toussaint. In fact, Toussaint may have even temporarily superseded Washington—in a sense, a better Federalist than the former president. It was Toussaint who was able to enact a constitution, maintain its authority, and to create the order and stability to which Federalists had always aspired but had failed to secure in the nation’s first decade. Toussaint faced no comparable internal dissention—no Shays, Fries, or Whiskey rebellions. No opposition party had formed to contest his legitimacy. Electoral defeat in 1800, then, was not only a sign of the people being led astray by irresponsible demagoguery but also an indictment of the incomplete program of republicanism that Federalists had envisioned and crafted.

By contrast, Democratic-Republicans railed against Toussaint’s rise and the quasi-independent state he had created. They identified him as a tyrant who lurked beneath a thin veneer of republicanism. They criticized Toussaint’s constitution, which installed him in power for life and gave him broad authority to censor the press, critiques not much different than those previously leveled against supposed monarchist John Adams and his infamous Alien and Sedition Acts. Moreover, Democratic-Republicans also began to draw out the implications of independence in Saint Domingue for race relations at home. The Aurora‘s Duane urged Congress to relax naturalization regulations so that more European whites could be enticed to immigrate to the southern states. This, he argued, would balance out racial demographics and help prevent an insurgency among domestic slaves. “[M]ore can and should be thought and done [on this subject],” he concluded, “than ought to be published.”

Thus, while Federalists depicted Toussaint as if he could, sans race and foreign origin, take a place in the pantheon of Founding Fathers and assessed Jefferson as increasingly inadequate, Democratic-Republicans leveraged racial anxieties surrounding Saint Domingue to cast Federalists as naively out of touch with the times and dangerously flirting with the nation’s potential destruction. In both cases, however, each used Toussaint as a means to score points in the ongoing partisan battles preceding and following regime change in the United States. Such partisanship occluded the more meaningful, if latent, truth that the passage of authority from Washington to Jefferson, from one Virginian to another, did nothing to resolve slavery’s intransigent grip on the republic.

Instead, partisans on both sides continued to produce biographical sketches of celebrity surrogates. The drive to elevate or disparage the nation’s founding figures both hid and symptomatically revealed this known unknown of America’s political unconscious. The substitution through displacement replayed the stilted drama of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, its awkward euphemisms for slavery—”Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit” (Article I, section 9)—and the twenty-year-long prohibition against discussing regulation of the slave trade itself (Article IX, section 1). Now nearing the end of that twenty-year period of institutionalized, collective repression, a contest between rival cults of personality repeated the original dynamic. Hagiography and character assassination covered what everyone knew but could not yet acknowledge as the childless Washington—a slaveholder, yes, but also the model of southern civility and benevolence—yielded to Jefferson, an abstruse, philosophizing coward, who slept with his own slaves and peopled the nation with his unacknowledged offspring.

Like Toussaint, Aaron Burr was similarly an object of desire and disgust. If the diverse attachments to Toussaint briefly named blackness and slavery as the underpinnings of partisan dispute, Burr soon came to fill and obscure that insight, a political, psychical, and deracinated surrogate. Though interest in Toussaint and his constitution was intense, it was also short lived. The fascination with Burr may be understood to extend the psychic and regionally differentiated reception of the Black Caesar. Burr allowed for the repression of the racial issue surrounding celebration or castigation of Toussaint. Gone but, like Freudian slips or symptoms of unconscious drives, still present, race became the unknown but known dilemma, its psychic energy tagged to Burr’s suspicious, mysterious character.

Leonora Sansay’s fictional experiments in Secret History unveil these unknown knowns, those repressed desires and practices that we pretend not to know about although they underlie or even undermine the values Americans consciously held dear. These are the issues brought to the fore when Sansay placed Aaron Burr on the title page of her inaugural publication, one that explicitly pivoted on the aftermath of the revolt on Saint Domingue. There she implied that a broadly held American fantasy had condensed Haiti, its black general, the idea of Black Republicanism, domestic slavery, and the developing and regional conflict over its future in the figure of Burr, that sexually suspect killer, that double-faced and self-interested traitor. She put innovative narrative strategies to the task of unpacking Americans’ vague but complex racial fantasies and in turn rejuvenated domestic fiction.

To conclude, I want to consider but one example from the novel itself where, as with the title and its intimate reference to Aaron Burr, history is recast as provocative, reshaped to indicate that more is going on behind the scenes. When Clara first visits General Rochambeau, who would be the last white French governor to rule Saint Domingue, at his government house in Cap François, she enters a hall decorated with military trophies and with walls each graced with the names of “some distinguished chief.” Clara boldly and perhaps flirtatiously remarks that Washington had no place in the display. This prompts Rochambeau, already thoroughly enthralled by Clara’s charms and ready to dispatch her husband so as to rid himself of a rival to her affections, to correct the oversight in advance of her next visit. A new panel has since been added reading, “Washington, Liberty, and Independence!” Not only do we see the name Washington used as a token for seduction; grouped with Napoleon and Frederic the Great, Washington’s image is also appropriated to the class of martial, European leaders. The reference to liberty and independence can only be ironic as Rochambeau continues his suppression of a slave revolt and exercises autocratic control over the remaining white inhabitants.

With Clara’s flight from Saint Domingue and, later, from marital turmoil, Sansay points toward an alternative, less cynical resolution all made possible only once the former slaves of Saint Domingue make their final push to claim independence. Thus, unlike other women authors from her era, Sansay did not retreat to the boarding school to compensate for a truncated access to civic participation. Rather, she found a utopian potential in Caribbean migration spurred by the disruptions of a massive slave revolt. The longed for reunion with Burr, the participation in his supposed conspiracy, and the use of his allure to reach for a publicly resonant voice together create powerful links between the disruptive Burr, the Haitian revolt, and a woman’s innovative use of fiction as a means of civic and social agency.

Further Reading:

Leonora Sansay’s Secret History; or The Horrors of St. Domingo and Laura are available from Broadview Press. A critical appraisal of the novel is Elizabeth M. Dillon’s “The Secret History of the Early American Novel: Leonora Sansay and Revolution in Saint-Domingue,” Novel 40:1/2 (2006): 77-105. Colin Dayan was the first to recognize Secret History‘s literary qualities in her book Haiti, History, and the Gods (Berkeley, Calif., 1995). On the diplomatic history of Haiti and the United States see Gordon Brown, Toussaint’s Clause: The Founding Fathers and the Haitian Revolution (Jackson, Miss., 2005) and Phillipe Girard’s recent article, “Black Talleyrand: Toussaint Louverture’s Diplomacy, 1798-1802,” in William and Mary Quarterly 66:1 (2009): 87-124. An English language collection of Toussaint L’Ouverture’s writings, including a translation of the 1801 constitution, is available from Verso with an introduction by Jean-Bertrand Aristide. There are many excellent books about the Haitian Revolution and Toussaint L’Ouverture more generally. Among the most recent are Laurent Dubois’s Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 2004) and Madison Smartt Bell’s Toussaint Louverture: A Biography (New York, 2007). There are also many good biographies of Aaron Burr, including but not limited to Nathan Schachner’s classic Aaron Burr, A Biography (New York, 1937) and Nancy Isenberg’s more recent Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr (New York, 2007).

Michael Drexler and Ed White, of the University of Florida, are completing a book entitled The Traumatic Colonel: The Burr of American Literature, in which the argument above is presented in greater detail and with a broader scope. One chapter, entitled “Secret Witness; or The Fantasy Structure of U.S. Republicanism,” will appear in Early American Literature 44:2 (2009). Another on Toussaint’s constitution in the U.S. press will appear in the Blackwell Companion to African-American Literature.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.3 (April, 2009).

Michael J. Drexler teaches American literature at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pa. His edition of Leonora Sansay’s Secret History and Laura is available from Broadview Press. He has also coedited Beyond Douglass: New Perspectives in Early African-American Literature (2008) with Ed White.