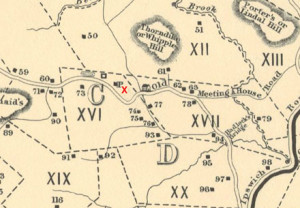

Reports of witches’ meetings in Salem Village in 1692

It is well known that the Salem witchcraft episode is different from any other witchcraft outbreak in New England. It lasted longer, jailed more suspects, condemned and executed more people, ranged over more territory—twenty-five different communities. And once it was over, it was quickly repudiated by the government as a colossal mistake, a great delusion. As historians Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum pointed out in the 1970s, the excesses of the Salem episode were caused by “something deeper than the kind of chronic, petty squabbles between near neighbors which seem to have been at the root of earlier and far less severe witchcraft episodes in New England.”

But what, exactly, was that “something deeper”? And how can we make sense of it today, as far removed as we are from the early modern residents of Salem? For the most part, scholars have paid more attention to the social, political, and psychological aspects of the witchcraft accusations and less to the world of witchcraft beliefs and fears expressed in the testimonies themselves. A small set of Salem court records (two dozen out of approximately a thousand Salem witch trials court documents) describe, sometimes in vivid terms, the witchcraft meetings in Salem Village and the threat they were perceived to pose. Although historians have not given these particular testimonies any special attention, they accepted the validity of the accusations to the authorities, and through the spring, summer, and fall of 1692, they played a significant role in propelling the legal process forward and ultimately in its spiraling out of control.

The dramatic descriptions of witches’ meetings and the danger they represented were immediately confirmed by the local ministers, and they proved convincing to the Salem magistrates as well. Most of these testimonies were used as eye-witness evidence at the grand jury hearings to obtain indictments against dozens of witchcraft suspects. At the end of the trials, critics and advocates alike would draw attention to the critical role these testimonies played in bolstering the trials.

The court records of the Salem trials contain over a dozen accounts of witches’ gatherings held in Salem Village. These meetings were, however, entirely spectral in nature and visible only to witchcraft suspects who confessed to witnessing them in court. From the beginning, the reports of witches’ meetings alarmed the authorities because they described not only bewitchments among neighbors but also Satan’s larger plan to undermine the village minister and his church. Witches were not only said to be targeting village church members, which was obvious to all, but also to be establishing their own church by holding satanic masses next to the village parsonage in a brazen attempt to supplant the Christian faith.

These claims—which posited an antithetical community, a satanic Salem in the midst of Puritan Salem—were unique and unprecedented. Nothing of this sort had ever been claimed by witchcraft suspects or accusers in New England. To be sure, New England Puritans long believed that their errand into pagan North America was a direct assault on Satan’s empire, and they knew that Satan was responsible for some of the unexplainable misfortunes that people suffered. Satan’s usual methods were to capture a few degenerate souls and use them to create mayhem among their neighbors or to incite the Indians to attack English settlements, as was happening in 1689. In 1692, however, it was revealed that Satan was also striking a blow directly at the spiritual core of New England Puritanism—the church itself. And it soon became apparent that Satan was recruiting agents from all over Essex County. As time went on, accounts of witches’ meetings revealed that destroying the Salem Village church was just the beginning. Satan’s ultimate goal was to destroy all the churches in the Bay Colony.

Salem Village was a separate parish of Salem Town, and it had long been racked by controversy over its ministers, causing the Salem authorities to intervene and appoint new preachers to the village church. In 1689-90 discord broke out over the newly ordained Reverend Samuel Parris, who was both an arrogant and conservative clergyman. Upon arriving in Salem Village he and his small group of followers instituted the restrictive and widely discarded old covenant rules for church membership, which required public confession of conversion and restricted baptism, in contrast to the more liberal half-way covenant. For years, the mother church in Salem Town, which the villagers had previously attended, had loosened the rules for membership. The reaction by most of the villagers was severe. Parris’s opponents stopped his salary, blocked the growth of the church, and curtailed baptisms of village children—actions that severely inflamed the conflict. Parris fought back for months in his sermons, warning about the wickedness of his opponents and the “wiles” of the devil. In January and February 1692, he declared that the devil was trying to “pull down” his new congregation, a charge that came very close to an accusation of witchcraft against unnamed “wicked and reprobate men (assistants of Satan).”

In mid-March, three weeks after the first accusations by two children in Parris’s house, the Reverend Deodat Lawson, a former minister of Salem Village, preached at the village at the request of Samuel Parris and the Salem magistrates. Lawson declared that discord over Parris’s ministry was one of the sources of the problem and proclaimed that God had loosed Satan upon the village because of “the Fires of Contention” within the village over its new minister.

The confessors took hold of this theme and wove it into their confessions with impressive effect. The authorities were entirely taken in by the vivid descriptions of witches’ meetings, something that critics would later emphasize. Under the specter of witches’ meetings said to be aimed at destroying the village ministry, an unprecedented and momentous claim, the New England tradition of legal caution towards witchcraft accusations completely evaporated.

The first to confess was Tituba, an Indian slave of Samuel Parris and one of the first three suspects. Parris allegedly beat Tituba prior to her appearance before the Salem magistrates and told her what to say. Whether or not this is true, Tituba cooperated and confessed volubly, and she was never brought to trial. She immediately testified against the two other village women accused with her, Sarah Good and Sarah Osburn, and then told of “seeing” them gathered in spectral form in the minister’s house with several other witches, some of whom came from Boston.

The judges wanted to know more and interrogated Tituba a second time in jail, arranging for three different recorders to take her testimony. She told the judges that the leader of the witches “tell me they must meet together” in Samuel Parris’s house. The court record of her second examination continues, in question and answer form,

Q. w’n did he Say you must meet together.

A. he tell me wednesday next att my m’rs house, & then they all meet together thatt night I saw them all stand in the Corner, all four of them, & the man stand behind mee & take hold of mee to make mee stand still in the hall.

Tituba added that the witches threatened to kill her and made her afflict the two girls in Parris’s house who initiated the accusations. She testified that she counted a total of nine witches’ signature marks in the devil’s book.

Tituba’s confirmation of the guilt of Good and Osburn and her testimony about the witches meeting in Parris’s house to attack his daughter and niece was a bombshell. It meant that Satan’s attack was led by outsiders who had recruited local villagers in a conspiracy against the village minister. For good measure, Tituba told the judges of her experience of flying to and from Boston on a pole with the other witches over the tree tops. Tituba’s tale, with its recurrent references to clandestine gatherings, captivated the magistrates’ imaginations, and, as the Reverend John Hale of nearby Beverly noted afterwards, set the stage for other confessions to follow. Subsequent confessors would admit that they attended witchcraft meetings in Salem Village, describe them as graphically as they could, and name several suspects whom they had “seen” at the meetings—usually people who had already been accused. These testimonies were recorded and later used as evidence to obtain indictments.

On March 21, three weeks after Tituba’s confession, the Reverend Deodat Lawson attended Martha Cory’s examination on charges of witchcraft. He reported that during her examination in the village meeting house, Cory’s young accusers responded to her charge that they were “distracted,” or mentally unbalanced. They boldly confronted Cory by asking “why she did not go to the company of Witches which were before the Meeting house mustering? Did she not hear the Drum beat?” This report of a witches’ meeting in the village was the first independent confirmation of Tituba’s initial report of witches gathering in Parris’s house, and it came from the court’s star witnesses.

A week later, eleven-year-old Abigail Williams, Parris’s niece, and seventeen-year-old Mercy Lewis, a servant in Thomas Putnam’s house, told the Reverend Lawson that they had just witnessed a performance of the devil’s mass in the village. The satanic mass that Williams and Lewis claimed to have seen was a counter ritual performed the same day as a public fast that was held in Salem Town to benefit the afflicted village girls. According to Lewis “they [the witches] did eat Red Bread like Man’s Flesh, and would have her eat some: but she would not; but turned away her head, and Spit at them, and said ‘I will not Eat, I will not Drink, it is Blood,’ etc.”

On Sunday, April 3, a Sacrament day at the village church, one of the afflicted girls told Lawson that she had seen the specter of Sarah Cloyce shortly after Cloyce had stormed out of the meeting house without taking communion. “O Goodw. C[loyce],” said Lawson’s informant, “‘I did not think to see you here!’ (and being at their Red bread and drink) said to her, ‘Is this a time to receive the Sacrament, you ran-away on the Lords-Day, and scorned to receive it in the Meeting-House, and Is this the time to receive it? I wonder at you!'” The implication was that Cloyce, a recently admitted church member and a sister of the accused witch Rebecca Nurse, had walked out of the church in anger and refused to take communion. Instead, she took the devil’s sacrament of human blood and human flesh at a satanic mass elsewhere in the village. The next day Sarah Cloyce was accused and joined her sister in jail.

Lawson was sympathetic to his successor, Parris, and believed in the girls’ spectral sightings. Already by the end of March, Lawson estimated that the witches “have a Company about 23 or 24 and they did Muster in Armes, as it seemed to the Afflicted Persons.” Lawson was the only person to record the young village accusers’ observations about witches’ meetings in the village. All later reports were made by defendants who confessed to witchcraft to save themselves and supplied more detailed accounts of witches’ meetings to bolster their confessions.

On April 20, fifteen-year-old accused witch Abigail Hobbs of Topsfield confessed that “the Devil in the Shape of a Man came to her and would have her afflict Ann Putnam, Mercy Lewis, and Abigail Williams, and brought their images with him in wood like them, and gave thorns and bid her prick them into those images, which she did accordingly … ” The wooden images, called “poppets,” represented the witches’ victims. Witches allegedly afflicted people by stabbing and twisting these images to “Torture, Afflict, Pine, and Consume” their victims, in the standard formula of the indictments. Like others before her, Hobbs worked a witch’s meeting into her story. As she explained, she “was at the great Meeting in Mr Parris’s Pasture when they administered the Sacram’tt, and did Eat of the Red Bread and drink of the Red wine att the same Time.”

Two days later, Abigail’s step-mother Deliverance Hobbs, who was also accused of witchcraft, made the sensational revelation that the high priest of the satanic masses was none other than the Reverend George Burroughs, an unorthodox Puritan minister and yet another former minister of the Salem Village, who now ministered to a congregation in the frontier settlement of Wells, Maine. According to Hobbs’s eye-witness account, “Mr Burroughs was the Preacher, and prest them to bewitch all in the Village, telling them they should do it gradually and not all att once, assureing them they should prevail.” And, predictably, Hobbs added that Burroughs orchestrated his conspiracy at a witches’ meeting. “He administered the sacrament unto them att the same time Red Bread, and Red Wine Like Blood … The meeting was in the Pasture by Mr Parris’s house … ” Hobbs also boldly declared herself to be a “Covenant Witch” and proceeded to name nine suspects at the devil’s sacrament, all of whom had been previously accused, to strengthen her story.

On June first, at the first sitting of the special court of Oyer and Terminer, the grand jury began to hear the cases of the dozens of suspects who were crowding the jails. Attorney General Thomas Newton sought additional testimony from Abigail Hobbs and twenty-year-old Mary Warren and interviewed them in jail. Hobbs and Warren cooperated fully and named fourteen more suspects whom they claimed to have seen at a witches’ Sabbath in Parris’s field. Hobbs named five, including Burroughs, and Warren named nine more and identified them as the people who had tortured her in an attempt to make her attend another devil’s sacrament in mid-May. Warren also identified Rebecca Nurse and Elizabeth Proctor, both jailed suspects from Salem Village, as the deacons (in spectral form) who assisted Burroughs at the meeting. These two witches “would have had her [Warren] eat some of their sweet bread & wine & she asking them what wine that was one of them said it was blood & better then our wine but this depon’t refused to eat and drink with them … ” Newton apparently wanted to obtain Hobbs’s and Warren’s sworn testimony about Sarah Good and John Proctor for their upcoming grand jury hearings, which he had planned for June and July, and he needed their “eye-witness” evidence in order to satisfy the two-witness rule required in capital cases. Testimonies about witches’ meetings had already played an important role in the escalating number of accusations and confessions before the trials took place in June, and they were clearly going to play an equally instrumental role in moving the trials forward from June through September.

In mid-July, elderly Ann Foster of Andover told the magistrates that she had flown on a stick in the air “above the tops of the trees” in the company of several other witches to meetings in Salem Village. The court records contain three of Foster’s accounts and all were selected for use at the September grand jury hearings. Foster attested that she saw Martha Carrier, a witchcraft suspect from Andover, sticking pins into poppets to bewitch two children in Andover, making one of them ill and killing the other. “[S]he futher saith that she hard some of the witches say that their was three hundred and five in the whole Country, & that they would ruin that place the Vilige … ” Salem magistrate John Higginson added the comment that Foster “further conffesed that the discourse amongst the witches at the meeting at Salem Village was that they would afflict there to set up the Divills Kingdome … “

By late summer, the notion that the devil was establishing a congregation of witches at Salem Village next to Parris’s house was well known. In neighboring Andover, accused suspects, urged on by their families and the authorities, confessed in large numbers and offered even more elaborate descriptions of witches’ meetings. Twenty-two-year-old Elizabeth Johnson Jr. of Andover told the court that “there were: about six score at the witch meeting at the Villadge that she saw … she s’d they had bread & wine at the witch Sacrament att the Villadfe & they filled the wine out into Cups to drink she s’d there was a minister att theat meeting & he was a short man & she though is name was Borroughs: she s’d they agreed that time to afflict folk: & to pull done the kingdom of Christ & to set up the devils kingdom …”

On August 29, forty-six-year-old William Barker Sr. of Andover offered the most detailed description to date: Satan initially recruited followers from the village because of discord over its minister; Satan’s congregation in Salem Village had grown to hundreds of followers; and Satan’s attack on the village was a prelude to his attack on all the churches in the Bay Colony.

… He said they mett there [next to Samuel Parris’s house] to destroy that place by reason of the peoples being divided & theire differing with their ministers Satans design was to set up his own worship, abolish all the churches in the land, to fall next upon Salem and soe goe through the countrey, … He sayth there was a Sacrament at that meeting, there was also bread & wyne … he has been informed by some of the grandees that there is about 307 witches in the country, … He sayth the witches are much disturbed with the afflicted persones because they are descovered by them, They curse the judges Because their Society is brought under, …

By October, the trials had clearly gotten out of control. No one was safe from accusation, the accusations were escalating, and the public was turning against the trials. The Boston ministers finally persuaded Governor Phips to put an end to the court of Oyer and Terminer. Phips also banned the reliance upon spectral evidence, and thereafter, no more spectral witches were seen in Salem Village. In January the newly created Superior Court of Judicature began to clear the backlog of cases and acquit the dozens of suspects languishing in jail.

Following the trials, critics and supporters took up their pens to dissect the trials and, in the process, drew attention once more to sensational testimonies about witches’ meetings. In a privately circulated “letter,” Thomas Brattle, a Boston mathematician and astronomer, wrote that tales of witches’ meetings were evidence of psychological delusion and judicial coercion and should never have been admitted in court.

That the witches’ meeting, the Devill’s Baptism, and mock sacraments, which they oft speak of, are nothing else but the effect of their fancye, depraved and deluded by the Devill, and not a Reality to be regarded or minded by any wise man …

More than that, many of these confessions had been forced by the “most violent, distracting, and dragooning methods.” Boston merchant Robert Calef’s trenchant criticism of the Salem trials, published in More Wonders of the Invisible World (1700), reinforced Brattle’s point about the court’s intimidating methods, especially outside the courtroom, which were calculated to generate confessions and more details about the meetings.

… concerning those that did Confess, that besides that powerful Argument, of Life … There are numerous Instances, too many to be here inserted, of the tedious Examinations before private persons, many hours together; they all that time urging them to Confess (and taking turns to perswade them) till the accused were wearied out by being forced to stand so long, or for want of Sleep, etc. and so brought to give an Assent to what they said; they then asking them, Were you at such a Witch-meeting, or have you signed the Devil’s Book, etc. upon their replying, yes, the whole was drawn into form as their Confession.

The Reverend John Hale, who witnessed some of the proceedings, wrote an account in which he tried to make sense of it all. He concluded that the testimonies about witches’ meetings played a crucial role in driving the witch trials forward.

[T]hat which chiefly carried on this matter to such an height, was the increasing of confessors till they amounted to near about Fifty … And many of the confessors confirmed their confessions with very strong circumstances … their relating the times when they covenanted with Satan, and the reasons that moved them thereunto; their Witch meetings, and that they had their mock Sacraments of Baptism and the Supper, … and some shewed the Scars of the wounds which they said were made to fetch blood with …

Cotton Mather, by contrast, took the confessions to be valid evidence that justified the court’s actions. In Wonders of the Invisible World (1693), which defended the trials, Mather claimed that “at prodigious Witch-Meetings the Wretches have proceeded so far as to Concert and Consult the Methods of Rooting out the Christian Religion from this Country.” Mather quoted at length from several accounts of satanic masses to prove his case and thus to justify the actions of the court.

Five years after the trials, government finally chose to face up its responsibility, siding with its critics rather than Mather. In a carefully worded proclamation for a day of fasting in January 1697, written by repentant witch-trials magistrate Samuel Sewall, the government asked God to forgive “whatever mistakes, have been fallen into … referring to the late Tragedie raised amongst us by Satan and his Instruments, through the awfull Judgment of God; He would humble us therefore and pardon all the Errors of his Servants and People that desire to Love his Name; and be attoned to His Land.” The witch trials, in other words, were a tragedy created by Satan not for the purpose of actually raising up witches but to cause widespread fear that this was the case. During this “late Tragedie,” the testimonies about witches’ meetings played a central role. Arising within the context of intense religious discord in Salem Village, these testimonies about a witchcraft conspiracy, involving satanic masses, the drinking of human blood and eating human flesh, the stabbing of doll-like effigies, and the destruction of Puritan religion, gave ultimate meaning to otherwise ordinary accusations among neighbors. Thus the accusations were driven forward until they caused “an inextinguishable flame,” in the words of Governor Phips, unlike anything seen in New England before.

Further Reading:

For the best and most recent accounts, see Mary Beth Norton, In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692 (New York, 2002) and Bernard Rosenthal, Salem Story: Reading the Witch Trials of 1692 (Cambridge, 1993). The complicated legal process involved in the Salem episode is thoroughly explained, for the first time, in the introductory essays to Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt (Cambridge, 2009) edited by Bernard Rosenthal. This volume also provides fresh scholarly transcriptions (with notes), and it is the most complete edition of the nearly one thousand court records discovered to date, including many previously unpublished manuscripts. And it presents a complete chronological arrangement of the court records.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.4 (July, 2009).

Benjamin C. Ray is professor of religious studies at University of Virginia and director of the NEH supported Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive. Ray has recently published articles on the Salem witch trials in the New England Quarterly and the William and Mary Quarterly.